St John’s Island: From Gateway to Getaway

St John’s Island was once home to new migrants, opium addicts and political detainees. Marcus Ng charts the island’s transformation from a place of exile to an oasis of idyll.

It’s well known that Stamford Raffles landed by the banks of the Singapore River on 29 January 1819 to establish a British trading port on the island.1 Most accounts of this colonial milestone, however, skim over the minor fact that a day earlier, Raffles’ fleet of ships had anchored off St John’s Island. This was where representatives of the local ruler – the Temenggong of Johor, Abdul Rahman – met and assured the British that Singapore harboured no Dutch settlers who would be hostile to rival powers.2

Early modern Singapore was a by-product of geographical serendipity coupled with commercial desperation. Raffles’ mission was driven by the British quest for a regional port that could rival Dutch-controlled Melaka. Raffles also knew that the island enjoyed regional pedigree as “the site of the ancient maritime capital of the Malays”.3 Beyond that, Singapore was largely terra incognita to Europeans.4

Siquijan to Sekijang

The islands that clustered along Singapore’s southern coastline, however, were already longstanding landmarks to sailors plying the waters between the Straits of Melaka and the South China Sea.

The Portuguese were undoubtedly familiar with St John’s Island. Portuguese-Bugis cartographer Manuel Godinho de Erédia marked two islands as “Pulo Siquijan” in a map he had drawn in 1613 that was part of a manuscript titled Declaracam de Malaca e India Meridional com o Cathay. In another map he drew in 1604, titled Discripsao Chorographica dos Estreitos de Sincapura e Sabbam. ano. 1604 (Chorographic Description of the Straits of Sincapura and Sabbam 1604 A.D.), Erédia sketched a maritime passage called estreito nouo (“New Strait”) which ran south of Pulau Blakang Mati (present-day Sentosa) before passing north of Pulau Sekijang and turning east.5

“Pulo Siquijan” was Erédia’s (mis) rendering of Pulau Sekijang, Malay for “barking deer island”. Passing sailors then played a centuries-old game of Chinese whispers, distorting “Sekijang” into “St John’s” by way of “Sijang”.6 Erédia’s depiction of two islands sharing the same name, however, was no error. Two neighbouring isles bore the moniker “St John’s” and were marked as such in charts, including one produced by French hydrographer and geographer Jacques-Nicolas Bellin in 1755 and another by the Honourable Thomas Howe in 1758.7 It was only in 1899 that one of the two St John’s islands – the eastern one – which housed a hospital for patients afflicted with beri-beri, was renamed Lazarus Island.8

In Malay, the islands continue to share a nomenclatural link: Lazarus Island is known as Pulau Sekijang Pelepah (pelepah means “palm fronds”), while St John’s Island is Pulau Sekijang Bendera (bendera means “flag”) on account of a flagstaff that stood on it between 1823 and 1833. According to H.T. Haughton, “these islands are supposed to be two roe-deer at which the spear-reef (Terumbu Seligi) off Blakang Mati is being aimed”.9 The tales that gave rise to these names, unfortunately, are lost, as are any deer that may have once inhabited these islands.10

Gone too are names that one Captain George Thomas assigned to nearby islands in the late 1700s.11 Hoping perhaps to expand the Biblical theme, he marked Pulau Tekukor (north of St John’s Island) as “Luke” and the Sisters’ Islands as “Mark” and “Matthew”. These names, however, failed to stick and only St John’s survived in later charts.

Gateway to Singapore

St John’s Island was not only Raffles’ gateway to Singapore. The hilly island, located south of the Singapore harbour, also became a crucial landmark for the fledging port on the mainland. Before Raffles left the settlement, he issued instructions “to establish a careful and steady European at St John’s with a boat and small crew, for the purpose of boarding all square sailed vessels passing through the Straits”.12 An apocryphal account credits one Loughony with this task of informing passing captains “that the port is open” for business.13 St John’s Island, by hosting this crew of heralds, was instrumental in placing Singapore on the mental maps of mariners at a time when news could spread only as fast as the swiftest craft.

St John’s turn on the frontlines of colonial enterprise was brief. By 1834, the island was all but abandoned. “The only inhabitant was an old Malay, whose small thatched habitation was surrounded by cocoa-nut, orange, guava, plantain, and other tropical fruit-trees”, observed a visiting naturalist, who added, “The view from the summit of this elevated island was both extensive and beautiful; the small islands near us were either covered by a wilderness of wood, or else the jungle was cleared away” for pineapple plantations.14

The pineapples were still extant in 1847 when Dr Robert Little – a medical practitioner who was appointed first Coroner of Singapore in 1848 – visited the two St John’s Islands. He wrote:

“… we crossed to 2 islands called Pulo Sakijang about 1¼ mile from Blakang Mati. On landing on the nearest we ascended a hill covered with pine apples [sic] and found one house with one inhabitant… from this island we pulled to the other of the same name, and found on the beach a colony of Bugis, consisting of 7 men and inhabiting 3 houses. This had been a settlement for 40 years, and they permitted no women to be located with them, the only reason they gave for this misogynistic feeling, was that women invariably quarrelled and prevented them from working.”15

The aim of Dr Little’s sojourn to St John’s was to investigate remittent fever (malaria), which he mistakenly believed was caused by miasma from dying coral reefs.16 Medical interest in St John’s Island came from other quarters in 1848, when a medical committee suggested the use of “St John’s or one of the neighbouring islands” for the segregation of leprous convicts.17 The subject was raised again in 1857 – when the leper population in Singapore had reached alarming levels – to no avail. However, in the end, St John’s Island was never used to accommodate lepers.18

Quarantine Island

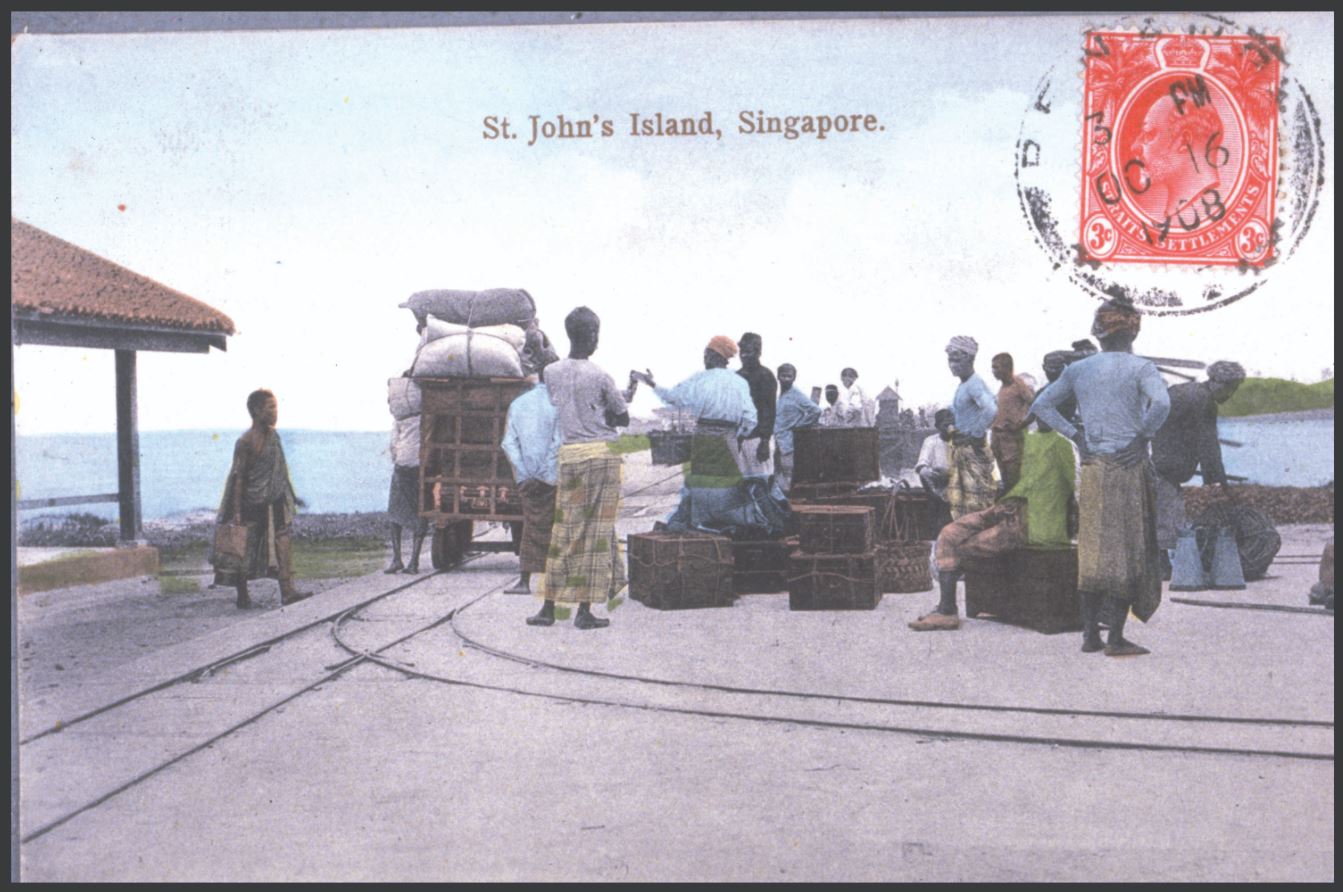

St John’s transformation into a rather less welcoming destination began in 1873, after a severe cholera outbreak in Singapore that claimed the lives of 357 people. Under pressure from the mercantile community, Andrew Clarke, the British Governor in Singapore, approved a proposal by Acting Master Attendant Henry Ellis to establish a lazaretto (a facility to isolate and treat patients with contagious diseases) on St John’s Island.

Ellis’ wishlist for the site included a steam cutter (patrol boat), a floating police station and a hospital as well as burial grounds on nearby Peak (Kusu) Island.19 St John’s stint as Singapore’s “Quarantine Island” thus began in November 1874 when the barely completed lazaretto took in between 1,200 and 1,300 Chinese passengers from the cholera-stricken S.S. Milton from Swatow (now Shantou), China.20

By 1908, the quarantine facility on St John’s had expanded to encompass the entire island, which was populated with sheds housing the occupants of infected or suspected ships,21 be they new migrants to Malaya or religious pilgrims returning from performing the Haj in Mecca.

In reality, quarantine was defined by the class of passage. First- and second-class cabin passengers could simply present themselves for clearance before disembarking, while hapless passengers in steerage (who shared a deck or hold) were quarantined for two to three days. From the 1920s, most cargo-hold travellers were required to transit at St John’s Island for inoculation before proceeding to Singapore, with migrants from China subject to at least a week’s quarantine.22

For the British, St John’s Island was an achievement “which every resident may be proud”. The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser reported in 1926:

“With thousands of Chinese arriving at Singapore every week, and with smallpox on two out of every four immigrant ships entering the port, Singapore and the Peninsula are nevertheless kept practically free from that disease… Certainly the treatment which the immigrants received on the island is about as pleasant an introduction to Malaya as they could expect. They arrive hungry, dirty and miserable after a deck passage through the China Sea, and they spend five blissful days – or it may be a fortnight – with nothing to do, wholesome food to eat, and the beaches of the island on which to lounge away the first hours of leisure they have known in their lives.”23

Another report in The Straits Times in 1935 feted St John’s as the “largest quarantine station in the world” − after New York’s Ellis Island and El Tor in Egypt − with the means to detain up to 6,000 people in 22 camps. The island then also housed “several hospitals for actual cases of smallpox, cholera, plague, chickenpox, measles and kindred diseases, and the barracks and temple for the 15 men of the island’s Sikh Police force, the gardeners’ quarters and mosque, the coolies’ and workmen’s quarters, the Coroner’s court and the lock-up”.24

Memories of Quarantine

Henry Ellis’ initial plans to use Peak (Kusu) Island as a burial ground were soon cut short when a community leader named Cheang Hong Lim raised strenuous objections to this idea. Instead, Lazarus Island took its place; from the early 20th century onwards, passengers who died upon or shortly after arrival were buried here.

Writing to the Colonial Engineer J.F.A. McNair in 1875, Cheang offered a glimpse into Kusu’s cultural life, which British authorities had overlooked. He wrote:

“… a small Island called Peak Island, lying opposite to this Colony of Singapore, has, for upwards of thirty years been used by many of the Chinese and native Inhabitants of this Settlement as a place for them to resort to at certain periods every year, for the purpose of making sacrifices, and paying their vows to certain deities there called ‘Twa Pek Kong Koosoo’ and ‘Datok Kramat’, and as that place has lately, to the great prejudice of their feelings, been desecrated by the interment therein of a number of dead bodies. Your Petitioner is desirous of applying for a Title to the same, in order to prevent that place from being any longer used as a Burial Ground.”25

Teo Choon Hong, who arrived in Singapore from Amoy (now Xiamen), China, in 1937, recalled his quarantine experience with the National Archives of Singapore in 1983. He said in Hokkien:

“I was quarantined on Kusu Island (later in the interview, he clarified that he had meant St John’s Island) as the British thought that there were germs on the lower berth of the steamer that might lead to infectious diseases. Only those on the lower deck were quarantined. Those who stayed in the cabins did not have to go. There was a class distinction…. Being quarantined on Kusu Island was inhumane. We were bossed around like chickens and ducks. The British saw us Chinese as beasts. After being given some rations, it felt like we were camping – we had to cook and eat there. I was quarantined for two days before being released.”26

Teong Eng Siong offered a more sanguine view of his stay on St John’s Island after he arrived from Foochow (now Fuzhou) in 1948:

“Every batch of people who came here had to stay at Qizhang Hill27 for a short three to five days, so as to ensure that there were no infectious diseases and such. After three or five days, I was allowed ashore…. We had three meals a day. Breakfast consisted of bread and milk tea. There were two small slices of bread. At that time, it was not enough. Then in the afternoon, it was lunch, and at night it was dinner. The meals all had eggs, and some stir-fried vegetables and fish. We had two time slots a day to shower, because at that time, the weather was hotter, hotter than now. It made us more comfortable. Living quarters-wise, there were many people living together in a big hall.”28

For Saravana Perumal, who came from Jaffna, Ceylon, in 1947, St John’s Island was an “isolated place”. “We were locked up in the camp,” he told the National Archives in 1983.29 “We were given rations, firewood, pots to cook and prepare our own food. It gave me a sort of fright there because of centipedes, cockroaches….”

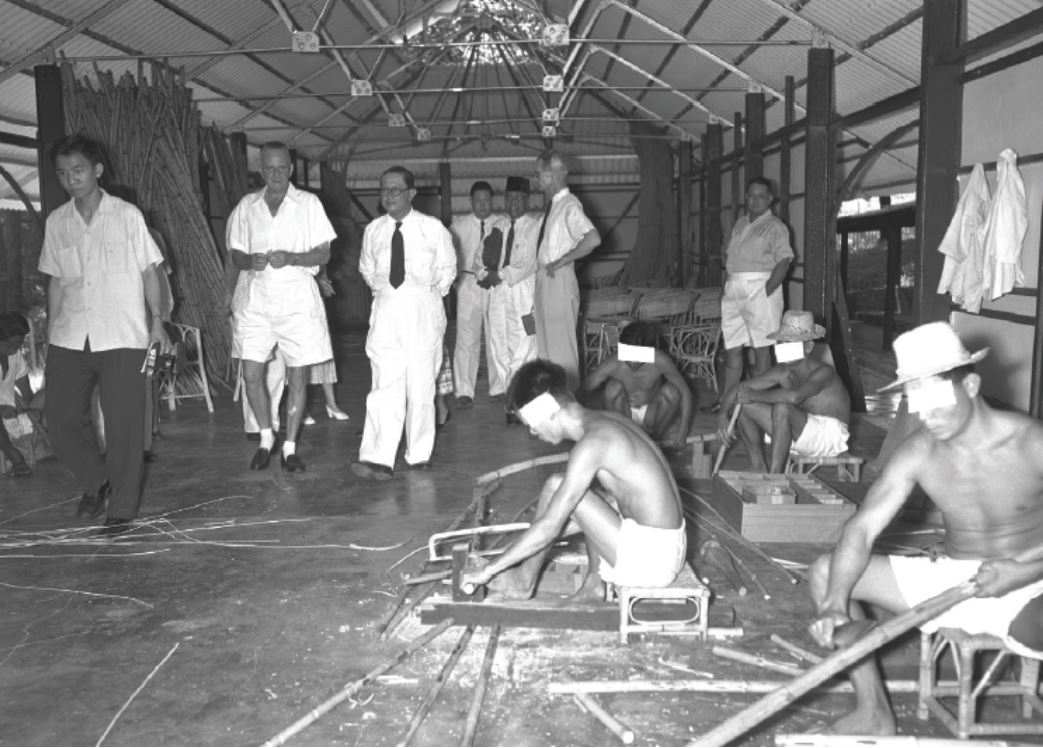

Years later, in 1955, Perumal returned to St John’s Island when he was transferred there to help establish an Opium Treatment Centre. This centre, he explained, trained opium addicts in various tasks for rehabilitation into productive society. “After a month, when they are certified fit for work, they were given the jobs of carpentry where they made tables, chairs, furniture, rattan work, tailoring….”30

The treatment centre at St John’s, which operated until 1975, was one of the island’s new functions after the war. But quarantine continued even after Singapore gained independence in 1965 as the government had adopted a precautionary stance against the risk of infection from deck passengers from China and India.31 It was only in 1971 that deck passengers from China were exempted from compulsory quarantine if they had valid health certificates.32 Those from India had to wait until 1973 for compulsory quarantine to end. St John’s quarantine centre officially closed on 14 January 1976.33

Island and Prison

In 1948, parts of St John’s Island were converted into a detention centre for political prisoners.34 Earlier, during World War II, the island had already acquired a political-military dimension when it housed Japanese and German civilians. During their stay, the Germans erected a Chinese-style moon gate by the island’s western shore, which still stands today.35

C.V. Devan Nair, who became Singapore’s third president in 1981, was among those detained on St John’s Island for anti-colonial activities. With little else to do but immerse himself in books, Nair dubbed the island “St John’s University”.36 His studies were interrupted one fateful day in 1952 by a visitor who described the island thus:

“There, amid beautiful old tembusu trees, stood some government holiday bungalows, and not far away, long rows of barrack-like buildings surrounded by chain-link fences for opium addicts undergoing rehabilitation. One of the bungalows was also ringed with chain-link topped with barbed wire. This housed the political detainees.”37

That visitor was a young anti-colonial lawyer named Lee Kuan Yew, and the fateful meeting between the two men led to Nair becoming one of the convenors of the People’s Action Party (PAP) at its founding in 1954. Nair would later be detained again in 1956, along with his party comrades Fong Swee Suan, Lim Chin Siong and Sydney Woodhull, until their release in 1959 when the PAP returned to power38 in the Legislative Assembly general election that gave Singapore the right to self-government and paved the way for Lee to become the first prime minister of Singapore.

An Island Getaway

By the mid-1970s, plans were afoot to convert Singapore’s southern islands into beachside holiday destinations.39 In part, these developments were aimed at replacing a stretch of the shoreline at Changi that would be buried under the new airport.40 St John’s Island would join Kusu, Sisters’ Islands and Sentosa to become an idyllic getaway from the confines of the congested mainland.

Meanwhile, before any transformation into island paradise could take place, St John’s island housed a final batch of “detainees”: about 1,000 Vietnamese refugees fleeing their homeland, who occupied the island between May and October 1975 as they awaited resettlement in the West.41

Since 1976, St John’s Island has become entrenched in the memories of a new generation of Singaporeans: as a site for offshore school camps, holiday bungalows, wet and wild weekends at its swimming lagoons protected by walls of rock. It is also fondly known as “cat island” to some, in reference to the abandoned felines that now outnumber children in the corridors of a former primary school established in the 1950s for families of staff residing on the island.42

Echoes of the past returned in 1999, when fences and barbed wire lined parts of St John’s Island as the authorities braced for a wave of illegal migrants fleeing political turmoil in Indonesia.43 Thankfully, the storm abated but the fences still stand, perhaps as a precautionary measure.

In the interim, the two St John’s Islands were conjoined by a causeway. Further plans for a “canal-laced marine village with recreational and mooring facilities and waterfront housing” failed to materialise as the business climate changed.44 Singaporeans, sparked perhaps by the preservation of Chek Jawa on Pulau Ubin, also began to see their islands less as “underutilised” spaces than as treasures of national and natural heritage.

New landmarks emerged in the 2000s: a Marine Aquaculture Centre where seabass are bred, and Singapore’s only offshore Marine Laboratory where researchers investigate diverse facets of marine science, ranging from giant clams to coral ecology and anti-fouling solutions for the shipping industry. Another milestone occurred in 2014 when St John’s western shore was designated part of the Sisters’ Islands Marine Park.45

A signboard at the end of the jetty invites visitors to explore the Marine Park’s Public Gallery on the island’s southern peak. The path from the jetty runs through compounds of barbed wire and beckons towards a row of low houses, home to the island’s last residents.46 Turn left and the trail winds past old bungalows, lush mangroves where fiddler crabs frolic at low tide, and patches of coastal forest. On the other side of the island are the former quarantine quarters turned campsites, which overlook beaches that still attract sizeable crowds on weekends.

The bustling city seethes beyond St John’s seawalls, always looming but still far enough to imagine that the island, as it was in the not-too-distant past, is not where Singapore ends, in space and thought, but a gateway to hope, to promise, to a future in harmony with its history and habitats.

Marcus Ng is a freelance writer, editor and curator interested in biodiversity, ethnobiology and the intersection between natural and human histories. His work includes the book Habitats in Harmony: The Story of Semakau Landfill (2009 and 2012), and two exhibitions at the National Museum of Singapore: “Balik Pulau: Stories from Singapore’s Islands” and “Danger and Desire”.

Marcus Ng is a freelance writer, editor and curator interested in biodiversity, ethnobiology and the intersection between natural and human histories. His work includes the book Habitats in Harmony: The Story of Semakau Landfill (2009 and 2012), and two exhibitions at the National Museum of Singapore: “Balik Pulau: Stories from Singapore’s Islands” and “Danger and Desire”.

NOTES

-

National Library Board. (2019, January). Stamford Raffles’s landing in Singapore written by Tan, Bonny. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia. ↩

-

Antechamber text, panel 3, “Arrival at Singapore” from Raffles’ Letters: Intrigues Behind the Founding of Singapore, National Library Gallery, 29 August 2012 to 28 February 2013. ↩

-

Raffles’ letter to the Duchess of Somerset, 22 February 1819, from Raffles’ Letters: Intrigues Behind the Founding of Singapore. ↩

-

European maps from the 16th–18th centuries variously marked Singapore as a town on the west coast of the Malay Peninsula, a city on the left bank of the Johor River, a promontory, a cape or simply as a sea passage. See Periasamy, M. (2015). The rare maps collection of the National Library. In Singapore. National Library Board, Visualising space: Maps of Singapore and the region (pp. 60–61). Singapore: National Library Board. (Call no.: RSING 911.5957 SIN). ↩

-

When did Singapore become an Island? Part III. (2015, February 8). Retrieved from History Delocalised blogspot; Nor-Afidah Abdul Rahman. (2016, January–March). A Portuguese map of Sincapura. BiblioAsia, 11 (4), 20–21; Gibson-Hill, C. (1954, May). Singapore: Notes on the history of the old strait, 1580–1850. Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 27 (1)(165), 163–214, p. 173. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Durai Raja Singam, S. (1939). Port Weld to Kuantan: A study of Malayan place names (pp. 250–251). Kuala Lumpur: Malayan Printers. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.5 RAJ-RFL). ↩

-

Bellin, J.N. [1755]. Carte réduite des détroits de Malaca, Sincapour, et du Gouverneur, dressée au dépost des cartes et plans de la Marine [Map]. Dépôt-Générale de la Marine; Howe, T. (1805, March 17). Sketch of the Straits of Singapore by The Hon’ble Thomas Howe April 1758 [Map]. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Government gazette. (1899, March 25). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Haughton, H.T. (1889). Notes on names of places in the island of Singapore and its vicinity. Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 20, 79. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Barking deer or kijang (Muntiacus muntjak) are native to Singapore but were hunted to extinction in the 20th century. There are no records of barking deer on St John’s Island, but two deer were relocated to the island in 1906. See Untitled. (1906, January 16). The Straits Times, p. 2; Deer hunt of St John’s. (1906, January 15). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Thomas, G. (1805, March 19). Sketch of the Straits of Sincapore by Capt George Thomas [map]. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Raffles’ instructions to Farquhar, Resident and Commandant of Singapore, 6 Feb 1819. See Buckley, C.B. (1984). An anecdotal history of old times in Singapore (p. 43). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 BUC-[HIS]). ↩

-

Gunner Loughony, first P.R.O. of Singapore. (1956, December 8). The Straits Times, p. 27. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Bennett, G. (1834). Wanderings in New South Wales, Batavia, Petir Coast, Singapore, and China: Being the journal of a naturalist in those countries during 1832, 1833 and 1834 (Vol. 2, pp. 218–221). London: Richard Bentley. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Little, R. (1848). An essay on coral reefs as the cause of Blakan Mati fever, and of the fevers in various parts of the east. The Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia, 2, 591–592. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Ng, M. (2017, Apr–Jun). Through time and tide: A survey of Singapore’s reefs. BiblioAsia, 13 (1). Retrieved from BiblioAsia website. ↩

-

Lee, Y.K. (1978). The medical history of early Singapore (p. 266). Tokyo: Southeast Asian Medical Information Center. (Call no.: RSING 610.95957 LEE). ↩

-

A 1938 report proposed the erection of an annexe “for the examination of immigrants for early signs of leprosy”, but it seems unlikely that the British would have considered housing lepers on the island in close proximity with thousands of new migrants. See St. John’s Island. (1938, April 26). The Malaya Tribune, p. 16. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lee, Y.K. (1978, January). Quarantine in early Singapore (Part 2). Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore, 7 (1), 81–87. Singapore: Academy of Medicine. (Call no.: RSING 610.5 AMSAAM). ↩

-

Legislative Council meeting 24 December 1874. (1875, January 9). The Straits Times, p. 2; The “Milton”. (1874, November 19). Straits Times Overland Journal, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Infected ships were defined as those where a case of infectious disease had occurred up to 12 days before arrival. Suspected ships were those where disease had occurred during the voyage but with no fresh cases in the 12 days preceding arrival. ↩

-

Teo, D., & Liew, C. (2004). Guardians of our homeland: The heritage of Immigration and Checkpoints Authority (pp. 26–27). Singapore: Immigration & Checkpoints Authority. (Call no.: RSING q353.59095957 TEO). ↩

-

Our newcomers. (1926, April 30). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

St John’s Island. (1935, June 1). The Straits Times, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Cheang, H.L. (1875, August 14). Wednesday, 11th August. The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Translated from Tan, B.L. (1983, September 16). (Interviewer). Oral history interview with Teo Choon Hong [Transcript of cassette recording no. 000328/7/2, pp. 22–23]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. [Note: Mr Teo’s reference to Kusu Island is likely an error, as this island was too small to house extensive quarantine facilities.] ↩

-

Mandarin for St John’s Island, which is probably a transliteration of “Sekijang”. ↩

-

Translated from Quah, I. (2002, February 1). (Interviewer). Oral history interview with Teong Eng Siong [Transcript of cassette recording no. 002605/10/1, pp. 5–6, 9–10 ]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Chew, D. (1983, September 16). Oral history interview with Saravana Perumal [Transcript of cassette recording no. 000335/17/9, p. 95]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Chew, D. (1983, October 6). Oral history interview with Saravana Perumal [Transcript of cassette recording no. 000335/17/11, pp. 116–117]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Quarantine: No change. (1967, December 19). The Straits Times, p. 24; T. Ramasamy. (1970, December 5). Untitled. The Straits Times, p. 20. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

No more quarantine for deck passengers from China. (1971, June 3). The Straits Times, p. 24. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Teo & Liew, 2004, p. 54. ↩

-

More prison space ready. (1948, July 3). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Kaite, Y. (1942, October 1). Inhuman acts of British towards Nippon internees. The Shonan Times, p. 4; Untitled. (1950, November 27). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Seow, F. (1994). To catch a tartar: A dissident in Lee Kuan Yew’s prison (Foreword). New Haven: Yale University Southeast Asia Studies. (Call no.: RSING 365.45092 SEO). ↩

-

Lee, K.Y. (1998). The Singapore story: Memoirs of Lee Kuan Yew (p. 158). Singapore: Simon & Schuster. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.57 LEE). ↩

-

Ministry of Culture. (1959, February 8). The battle for merger – (from right) C V Devan Nair, Fong Swee Suan, S Woodhull and Lim Chin Siong at St John’s Island detention camp. The picture was taken by Lee Kuan Yew when he paid them a visit on Chinese New Year day in 1959 [Photograph] [Online]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Holmberg, J. (1976, December 3). Islands in the sun. New Nation, pp. 10–11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Wong, P.P. (1992). The newly reclaimed land. In A. Gupta & J. Pitts (Eds.), Physical adjustments in a changing landscape: The Singapore story (p. 255). Singapore: Singapore University Press, National University of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 915.95702 PHY-[TRA]) ↩

-

St John’s Island to become holiday resort. (1976, January 23). The Straits Times, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Last 80 refugees get set to leave St John’s. (1975, October 22). The Straits Times, p. 19. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Nanyang Technological University Cat Club. (2016, December 27). Heaven is filled… with cats. Retrieved from NTU Cat Management Network website. ↩

-

Lee, J. (1999, February 25). Barbed wire, fences go up at St John’s. The Straits Times, p. 28. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore. Parliament. Official reports – Parliamentary debates (Hansard). (1996, October 28). Reclamation (Southern Islands) (Vol. 66, cols. 841–842). Retrieved from Parliament of Singapore website. ↩

-

National Parks Board. (2017, December 14). Sisters’ Island Marine Park. Retrieved from National Parks Board website. ↩

-

Azim Azman. (2015, May 18). Meet the last two people who still live on sleepy St John’s Island. The New Paper. Retrieved from AsiaOne website; Zaccheus, M. (2017, February 23). Last islanders likely to get to remain on St John’s Island. The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. [Note: Sadly, one of the last residents, Mr Mohamed Sulih, passed away later in the year.] ↩