Through Time And Tide: A Survey of Singapore’s Reefs

The reefs that fringed Singapore’s coastline and islands have served for centuries as maritime markers, fishing grounds and even homes for island communities. Marcus Ng rediscovers the stories that lurk beneath the waves.

Living reefs off Serapong on the northeast coast of Sentosa. Photo taken by Ria Tan on 23 May 2011. Courtesy of WildSingapore.

Living reefs off Serapong on the northeast coast of Sentosa. Photo taken by Ria Tan on 23 May 2011. Courtesy of WildSingapore.If the tides are high

It never will appear,

That little winking island

Not very far from here;

But if the tides are low

And mud-flats stretch a mile,

The little island rises

To take the sun awhile.

– Margaret Leong 1

In 1847, Dr Robert Little, a British surgeon, set off on a series of tours to Singapore’s southern islands, beginning with the isle known as Pulau Blakang Mati (present-day Sentosa).2 His journeys were no joyrides; the good doctor was investigating the source of “remittent fever” – a form of malaria – that had killed some three-fourths of the men posted to a signal station at Blakang Mati. The station was indispensable to navigation in the straits, but as no men were willing to serve at the ill-fated site, it was abandoned in 1845.

In the mid-19th century, malarial fever was often blamed on miasma or bad air that emanated from decaying vegetation in swamps or, in the case of Pulau Blakang Mati, its dense pineapple plantations. Being an annual crop, the remains of every harvest were often left to rot; this led to the belief that the decaying leaves emitted miasmatic vapours that infected nearby residents.

Dr Little, however, held a different theory, believing that the miasma originated from coral reefs. During the 19th century, extensive fringing reefs lined Singapore’s southern shores and islands while isolated or patch reefs, known to locals as terumbu or beting, abounded in the straits. Although the doctor must have been familiar with these habitats, he found cause to regard them as less a treat than a threat. He explained:

“Wherever we have coral reefs exposed at ebb tide we have a great destruction of coralline polyps, and a decomposition of animal matter carried on in a gigantic scale… If malaria is produced from animal decomposition on land, and we have a similar decomposition at sea, I think I am entitled to make my first deduction, that wherever a coral reef is exposed at low tide, decomposition will go on to an extent proportioned to the size of the reef and that malaria will be the result.”3

For all his misplaced suspicions, Dr Little’s initial encounters with Blakang Mati’s pristine reefs betrayed more than a tinge of admiration for their alien beauty. He was moved to write:

“At low water spring tides, the whole of these reefs are uncovered, so that by lying on the reef, one can look down into a depth of from 4 to 9 fathoms, like as a school boy does on a wall and looks at the objects below, which here are living corals of many and wondrous shapes, with tints so beautiful that nothing on earth can equal them. While the lovely coral fish, vying with their abodes in the liveliness of their colours, are to be seen peeping out of every crevice, which at full tide has but a few feet of water to cover it.”4

Dr Little hit an epidemiological deadend,5 but his expeditions to Blakang Mati, St John’s and Lazarus Islands as well as now-forgotten isles such as Brani, Seking, Sakra and Pesek, offered a rare if fleeting window to Singapore’s reefs and the communities who lived off them.

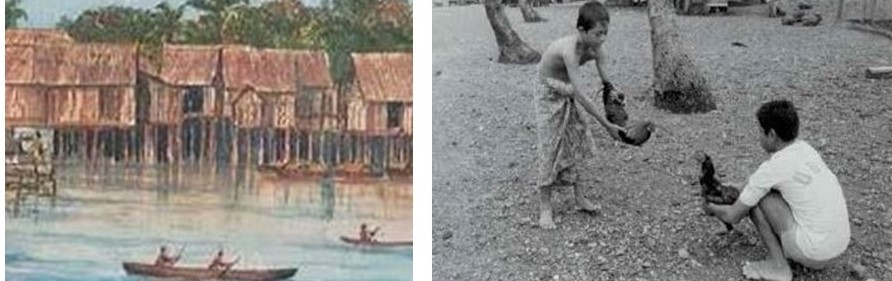

(Left) This painting from the 1830s depicts a cluster of wooden houses perched on stilts on Pulau Brani. In the 1960s, residents were asked to resettle on mainland Singapore to make way for the construction of a naval base. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

(Left) This painting from the 1830s depicts a cluster of wooden houses perched on stilts on Pulau Brani. In the 1960s, residents were asked to resettle on mainland Singapore to make way for the construction of a naval base. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.(Right) Two boys playing with their pet roosters in a Malay kampong on Pulau Seking, an offshore island that is now part of Pulau Semakau, 1983. Quek Tiong Swee Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Danger at High Water

Singapore’s reefscape posed no medical threat, but these maritime structures were for centuries cause for other mortal concerns. Jan Huyghen van Linschoten, a 16th-century Dutch merchant, warned captains to steer clear of areas “full of Riffes and shallowes” (reefs and shallows) as they sailed past Pasir Panjang en route to China. The 19th-century English hydrographer James Horsburgh would repeat this caution, describing the Singapore Straits as “united by reefs and dangers, mostly covered at high water”.6

The Europeans who first ventured into the straits had few or no names for the reefs that barred their passage. (One exception was Sultan Shoal, now the site of an exquisite lighthouse, which Horsburgh explained was named after a ship of this name that ran aground on the reef in 1789.) These platforms of living rock were usually hidden under the waves, too deep to be visible but high enough to scrape or worse, sunder a stray hull.

But from the mid-19th century, a few toponyms began to emerge, as the words and worlds of native pilots, boatmen and islanders who knew these waters for generations by heart filtered into the mental, and eventually printed, charts of foreign cartographers to give shape and significance to these submarine forms.

An 1849 map is perhaps the first to mark “Ter Pempang”, west of Pulau Bukom, which lies off the southern coast of Singapore. “Ter” is short for terumbu, Malay for a reef that is visible only during low tide. It is less clear what “Pempang” refers to. One possibility is that pampang means “to stretch out before one”.7 Another Malay word, bemban, denotes a fish trap as well as Donax canniformis, a fibrous shrub used to weave these traps.8

Both etymologies are apt; fishermen visited (and still frequent) these reefs to set traps weighed down by coral chunks and checked at regular intervals for stingrays and groupers. And these reefs indeed rise with the falling tide “to stretch out before one”, forming an expanse of land, a shimmer of sand and shoal where minutes ago there was bare sea. But in an hour or two, this ephemeral landscape will vanish once more as the waters return to shield the reef and its builders from sun and sight.

Intriguingly, the 1849 map indicated the presence of a hut on Terumbu Pempang as well as another on Pulo Pandan. These huts must have been set above the highest tide point, perhaps as shelters for fishermen from nearby islands. No trace of any such structures survive today; instead, Terumbu Pempang Laut (one of six adjacent reefs bearing the appellation “Pempang”) hosts a warning beacon, while a large sign on Terumbu Pempang Darat announces the presence of buried high voltage cables.

As for Pulo Pandan, there is sign of neither hut nor island today. The only clue that a landmass existed in this patch of sea between Pasir Panjang and Bukom is a trio of warning beacons and a ring of buoys that are not always heeded by ships, which run aground on the reef every now and then.9 There is also no trace of Pulo Pandan on modern charts, just a cluster of contours marked collectively as the Cyrene Reefs, the largest of which is named Terumbu Pandan.

Low Tide Treasures

Pulo Pandan may be long gone (See text box below), but life persists, at least under the waves. Early descriptions of Cyrene Shoal’s natural wealth still ring true today, for the reef harbours marine biodiversity that makes it, in the words of Ria Tan, a veteran nature conservationist, the “Chek Jawa of the South”. One visitor in the 1960s recalled “emerald waters” and “deep chasms which in good visibility could rival the view of the Grand Canyon”.10 Marine biologists have recorded 37 genera of corals and seven seagrass species at Cyrene Shoal, as well as large numbers of knobbly sea stars (Protoreaster nodosus) and signs of endangered dugongs on the reef’s seagrass bed.11

Cyrene Reef is home to a large population of knobbly sea stars. Photo taken on 22 July 2012. Courtesy of Marcus Ng.

Cyrene Reef is home to a large population of knobbly sea stars. Photo taken on 22 July 2012. Courtesy of Marcus Ng.Such natural bounty would have been familiar to the people who once dwelled in the straits. Up until the mid-1970s, womenfolk in Pulau Sudong, an island southwest of the Pempang reefs, “regularly collected sea foodstuffs from the island’s fringing reef”,12 some 12 times the size of the island, before the reef was reclaimed in 1977. The women also ventured to a nearby patch reef to harvest agar agar (gelatinous seaweed), gulong (bêche-de-mer) and undok (seahorses). Chew Soo Beng, who documented the islanders before their eviction to the mainland, described a scene that has long vanished from the straits:

“During ebb tide, the outer reaches of the reef to the west of Pulau Sudong are completely exposed… Groups of women row their kolek [a small sea craft] to different parts of the exposed portion of the reef to gather sea produce… When both the tide and the sun were low, the gay chatter of the women at work would drift into the village where the men, excluded from the offshore merriment, conversed beneath their favourite pondok [hut]. The reef was called Terembu Raya (Big Reef)13 by the fishermen who set their small fish traps at the edge of it.”14

Lost Reefs

Pulo Pandan’s slow erosion into the Terumbu Pandan reef was probably the natural consequence of storms and currents that swamped the erstwhile island. Conversely, other local reefs have been shaped by man to become new islands, coves and port terminals. South of Jurong, Terumbu Pesek was reclaimed15 as a pig pen in 1985, and now forms part of Jurong Island. Beting Kusah,16 a sand bank off Changi, now lies under the airport tarmacs. In contrast, Beting Bronok (named after an edible sea cucumber) has escaped the extensive reclamation that befell nearby Pulau Tekong and was designated a Nature Area in 201317 for its rare marine life such as knobbly sea stars, thorny sea urchins and baler shells.

Buran Darat, a coral patch named after “a kind of sea-anemone of a light green colour and eaten by the Chinese”, was reclaimed in the late 1990s to create the Sentosa Cove luxury resort.18 Terumbu Retan Laut, a reef off Pasir Panjang, was reclaimed in the 1970s to provide anchorage19 for lighters evicted20 from the Singapore River and eventually buried under steel, concrete and cranes, as reported in The Straits Times in 1995: “Terumbu Retan Laut on the west coast will be partially dredged away… What remains of it will be used for port terminal development on the west coast.”21

The same newspaper report laid bare the fate of some of the reefs and islets off Blakang Mati which so beguiled Dr Little in the 1840s: “A bigger Sentosa Island include[s] three other islands: Buran Darat, Sarong Island and Pulau Selegu. Terembu [sic] Palawan, formerly a reef off the southern coast of Sentosa, has been reclaimed and is now an island called Pulau Palawan.”

Today, Sentosa’s surviving coral reefs cling to the island’s peripheries: off Serapong at its northeast and along Tanjong Rimau on the northwest, a sliver of natural rocky coastline which guards the colonial era Fort Siloso. Along the mainland, there are also fringing reefs along less accessible parts of East Coast Park and Tanah Merah, whose ultimate fate probably hinges on future discourses on land-use and habitat conservation in Singapore.

PULO PANDAN: AN ISLAND TURNED REEF

Pulo Pandan is now reduced to Terumbu Pandan and forms part of the Cyrene Reefs. But in centuries past, Pulo Pandan loomed much larger, and even stood out as a landmark in the straits. The island was signposted by Jan Huyghen van Linschoten in 1596, when the Dutchman described the journey eastward on the Selat Sembilan (“Straits of Nine Islands”) between Pasir Panjang and the present Jurong Island:

“… running as I said before along by the Ilands on the right hand, and coming by the aforesaid round Island [Pulau Mesemut Laut22], on the right at the end of the row of Ilands whereby you pass, you shall see a small flat Iland [Cyrene Shoal], with a few trees, having a white sandy strand, which lieth east and west, with the mouth of ye Straight of Sincapura [Keppel Harbour], which you shall make towards….”23

The seashore pandan (Pandanus tectorius), a native plant associated with sandy beaches, may have been the tree that lent its name to Pulo Pandan. By 1848, however, Pulo Pandan had been denuded of vegetation but gained a new toponym,24 as the Singapore Free Press noted: “Called by the Malays Pulo Pandan, and by the English Cyrene shoal; the trees have all disappeared, but aged natives say that there were many trees on the reef in former times, hence the Malays call it a Pulo or Island.”25

By the 1890s, whatever remained of the Pulo had vanished, and the Descriptive Dictionary of British Malaya had this to say of it: “[Cyrene] Shoal… presents a brilliant appearance at low water, being covered with live corals and shells, many of the most brilliant colours. It is a favourite hunting ground for conchologists.”26

The living reefs of Cyrene Shoal, off the southwestern coast of Singapore. Photo taken by Ria Tan on 22 March 2007. Courtesy of WildSingapore.

The living reefs of Cyrene Shoal, off the southwestern coast of Singapore. Photo taken by Ria Tan on 22 March 2007. Courtesy of WildSingapore.

Pulo Pandan presents for historians and cartographers, if not a shifting target, at least a sinking one – an island that long guarded the western entrance to Keppel Harbour but which lost over time its land, trees and name. After the isle vanished, port authorities deemed it a shipping hazard and placed lights and signs on the site to prevent collisions.27

Further insights on this reef are provided by another doctor, Carl Alexander Gibson-Hill, the Raffles Museum’s last expatriate director. In 1951, Gibson-Hill set sail to retrace Linschoten’s sailing route and determine the fate of the Old Straits of Singapore, which ran past Pasir Panjang and through Keppel Harbour but fell into disuse in the early 17th century. Cyrene Shoal would prove pivotal in his quest, as Gibson-Hill would write of Linschoten’s “small, flat land”:

“It is clear that this small sandy island with a clump of trees (probably coconut palms) on it of Linschoten’s account was at the eastern end of Cyrene Shoal, and it undoubtedly afforded a most valuable mark to anyone sailing through the two straits. The sandy strand survived until the last century, but apparently by 1797 it boasted only one tree. Presumably it was slowly breaking up during this period.”28

Gibson-Hill believed that the island was still extant in the 1820s, when Captain James Franklin marked it as Pulo Busing in an 1828 map. “Busing” may have been derived from busong, Malay for “a spit of sand”, but Gibson- Hill suggested that it was more likely a corruption of pusing (“to turn”), as the sight of the island’s shimmering sands in the distance was a cue for mariners to alter their course towards Keppel Harbour. Certainly, Cyrene Shoal’s significance as a landmark was felt by its absence, for Gibson-Hill was vexed as he sailed in the path of Linschoten’s wake and concluded:

“There is no doubt that the old route was an easy one to follow, coming from the west, so long as there were a few trees on the white, sandy islet on Cyrene Shoal… The absence of the original mark was very noticeable when I went over Linschoten’s course from Pulau Merambong eastward… and one felt that the disappearance of the trees might have been one of the factors that led to the final disuse of this route.”29

Shoals of Contention

Pulau Seringat, which was conjoined with Lazarus Island (Pulau Sekijang Pelepah) off the southern coast at the turn of the 21st century, offers a glimpse into the possibilities that face Singapore’s reefs. Where the island now stands was once a tidal islet known as Pulau Rengit, which refers to either a sandfly or a freshwater shell.30 Another account from 1923, however, cites the alternate moniker of Pulau Ringgit to explain that the islet was “named by reason of the fact that the ninety or more Malay fishermen and the one Chinese store-keeper who supplies their needs, pay a nominal annual rent of a dollar for the privilege of living a congested existence there”.31

Within a decade, however, most of the islanders would leave their home, which a 1935 article described as “an almost barren, low-lying stretch of coral”. The same report added of the residents: “They have now been moved – there are only a few dozen of them left – to a neighbouring islet which suffers less from the inundations of high tides.”32 It would appear that the few families that remained on Pulau Rengit eventually all moved to the mainland. Tijah Bte Awang, a villager born on Pulau Rengit, recalled:

“When I was growing up on Pulau Seringat, which some called Pulau Rengit, I remember it as one with no trees – just land, with one small mosque surrounded by 15 houses… our homes were built on stilts and placed side by side facing the sea… I remember in 1930, our island was not safe. The authorities feared that the sea would swallow up the island during extreme high tide or during a storm… I can’t remember exactly when we left Pulau Seringat. I may have been in my teens when our family made the permanent shift to Lazarus Island.”33

In the 1970s, Pulau Rengit was earmarked as a “holiday island”.34 Some 12.2 hectares of reef were reclaimed, but little else took place until the late 1990s when the government approved a more ambitious programme to reclaim 34 hectares of foreshore, seabed and reefs, and link up Rengit with St John’s and Lazarus islands to form a “canal-laced marine village with recreational and mooring facilities, and waterfront housing”.35

The impending loss36 of Pulau Rengit was mourned by Singapore’s nascent marine conservation movement, which had been calling for the protection of local reefs since the early 1990s. But little could be done other than a salvage operation by the Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research (RMBR; now Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum) to collect and document the reef’s marine life. The experience, however, would prove to be a catalyst that shaped subsequent conservation campaigns. N Sivasothi, then a RMBR research officer who took part in the salvage, recalled:

“The small team that landed on the reef was there… [to] collect, record and preserve as many specimens as physically possible before it was finally lost to land reclamation. The reef revealed rather surprising finds – numerous Neptune cups [a rare sponge], cushion stars, giant clams, crabs, octopus, fish, sea stars and colourful corals including spectacularly red sea fans….37 When I saw the Pulau Seringat reefs before their reclamation in August 1997, I felt great regret that very few Singaporeans had experienced the beauty of this reef. It remains to this day the precious but private memory of very few.”38

In 2001, when word got out that Chek Jawa at Pulau Ubin was slated for reclamation by year-end, the marine conservation community felt, as Sivasothi put it, that “this time, we could do better”. They mobilised, with the help of the then burgeoning internet, to invite Singaporeans to a “last chance to see” Chek Jawa and its diverse marine life. The memory and lessons of Pulau Seringat were still fresh and the experience prompted the museum to initiate large-scale walks at Chek Jawa to share the beauty and biodiversity of this shore with the public.

Smooth ribbon seagrass (Cymodocea rotundata growing in abundance at the seagrass lagoon at Chek Jawa. Photo taken by Ria Tan on 27 November 2004. Courtesy of WildSingapore.

Smooth ribbon seagrass (Cymodocea rotundata growing in abundance at the seagrass lagoon at Chek Jawa. Photo taken by Ria Tan on 27 November 2004. Courtesy of WildSingapore.Teams of volunteers led walks that exposed Chek Jawa to thousands of visitors, while press coverage of the campaign gave rise to broad-based appeals for the preservation of the coastal wetland. At the eleventh hour, on 20 December 2001, the government announced a 10-year deferment of reclamation for Chek Jawa.

To Sea, to See

The zeitgeist of marine conservation that accompanied Chek Jawa persisted in the decade that followed. Instead of bulldozers, Chek Jawa received a coastal boardwalk and continues to host popular intertidal walks.39 Riding on this wave of interest in the marine environment, avid divers began offering guided dive tours of the reefs off Pulau Hantu (south of Pulau Bukom) from 2003.40 Two years later, even Singapore’s only landfill, built in 1999 at Pulau Semakau, got into the game by launching guided walks to the island’s reef flat.41

Rather fittingly, Singapore’s first marine park was carved out on the doorstep of Pulau Seringat, the former reef that had fermented the movement to save Chek Jawa. Unveiled on 12 July 2014, Sisters’ Islands Marine Park includes the twin Sisters’ Islands as well as reefs at St John’s Island and Pulau Tekukor. The marine park, which hosts regular intertidal walks and offers a dive trail for more intrepid explorers, has played no small part in rekindling a sense of the sea, and by extension a sense of islandness, which many Singaporeans have probably lost (or never learned) as the straits retreated42 and bulldozers and dredgers moved in to create land for a growing population.

To board a ferry or bumboat bound for the southern islands and reefs43 from the pier at Marina South is to tread back in time and catch sight of the mainland as sailors and sojourners once beheld it – a strip of promised land sandwiched between the sky and seething sea.

High tide at the Chek Jawa boardwalk. Photo taken by Ria Tan on 19 October 2008. Courtesy of WildSingapore.

High tide at the Chek Jawa boardwalk. Photo taken by Ria Tan on 19 October 2008. Courtesy of WildSingapore.It is also a trip, not to the southern margins of an island nation, but to where Singapore first took shape and entered the imagination as an entity, an island at the junction of empires that first enthralled a Palembang prince and later an employee of a British trading company – a point of departure from landlocked vistas to an archipelago of reefs, shoals and islands, a landscape that remains to this day in flux and in thrall to the tides.

Marcus Ng is a freelance writer, editor and curator interested in biodiversity, ethnobiology and the intersection between natural and human histories. His work includes the book Habitats in Harmony: The Story of Semakau Landfill (2009 and 2012), and two exhibitions at the National Museum of Singapore: “Balik Pulau: Stories from Singapore’s Islands” and “Danger and Desire”.

Marcus Ng is a freelance writer, editor and curator interested in biodiversity, ethnobiology and the intersection between natural and human histories. His work includes the book Habitats in Harmony: The Story of Semakau Landfill (2009 and 2012), and two exhibitions at the National Museum of Singapore: “Balik Pulau: Stories from Singapore’s Islands” and “Danger and Desire”.

NOTES

-

The island Margaret Leong described is really a reef, as it vanishes at high tide. See Leong, M. (2011). Winking island (p. 16). In S. Lim & A. Poon. (Eds.), The ice ball man and other poems. Singapore: Ethos Books. (Call no.: JRSING 811 LEO) ↩

-

Renamed Sentosa in 1970, the island’s ominous Malay name, literally “behind dead island”, was thought to have stemmed from its pestilential reputation. However, the toponym Blacan Mati was already in use by the 1600s. ↩

-

Little, R. (1848). On coral reefs as a cause of the fever of the islands near Singapore. In J.R. Logan, (Ed.). The Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia, 2, 572–599, p. 599. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

The mystery was solved only in 1886 when a French surgeon, Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran, discovered microscopic parasites in the blood of malaria victims. It took another decade before British doctor Ronald Ross confirmed that mosquitoes were the vectors that transmitted the microbes. ↩

-

Untitled. (1848, November 2). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1835–1869), p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Horsburgh, J. (1841). India Directory, or, directions for sailing to and from the East Indies, China, Australia, and the interjacent ports of Africa and South America (Vol.2, p. 266). London: W. H. Allen & Co. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Winstedt, R. (1964). A practical modern Malay-English dictionary (p. 133). Kuala Lumpur; Singapore: Marican. (Call no.: Malay RSING 499.230321 WIN) ↩

-

Burkill, I.H. (2002). A dictionary of the economic products of the Malay Peninsula (Vol. 1, p. 868). Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Ministry of Agriculture, Malaysia. (Call no.: RSEA 634.9095951 BUR); Winstedt, 1964, p. 25. ↩

-

Taiwan trawler runs aground (1983, June 30). The Straits Times, p. 15; Ferry with 40 aboard runs aground. (1998, December 6). The Straits Times, p. 27. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Destroying Singapore’s undersea treasures. (1968, April 4). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum. (2017). Cyrene Reef. Retrieved from The DNA of Singapore website. ↩

-

Walter, M.A.H.B., & Riaz Hassan (1977). An island community in Singapore: A characterization of a marginal society (p. 22). Singapore: Chopmen Enterprises. (Call no.: RSING 301.4443 WAL) ↩

-

Terumbu Raya still exists, and lies between Pulau Sudong and Pulau Semakau. ↩

-

Chew, S.B. (1982). Fishermen in flats (p. 36). Clayton, Vic.: Centre of Southeast Asian Studies, Monash University. (Call no.: RSING 301.4443095957 CHE) ↩

-

Work to start on $13m pig project island. (1985, April 18). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Haughton, H.T. (1889). Notes on names of places in the island of Singapore and its Vicinity. Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 20, p. 76. Retrieved from JSTOR via eResources website; Beting refers to a partially submerged sand bank, while kusah was thought to be a corruption of susah, meaning “difficult”. ↩

-

Tan, W. (2013, February 1). Three more nature areas to be conserved under land use plan. Today, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Haughton, 1889, p. 77; National Library Board. (2016). Sentosa Cove written by Chew, Valerie. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

Lighters’ new mooring site. (1983, May 19). The Straits Times, p. 17. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Low, A., & Wong, K.C. (1984, December 11). The old men of the sea. The Straits Times, p. 18. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tan, H.Y. (1995, November 22). Singapore islands get new names with reclamation. The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Now part of Jurong Island. ↩

-

As quoted and annotated by Carl Alexander Gibson-Hill. See Gibson-Hill, C.A. (1954, May). Singapore: Notes on the history of the Old Strait, 1580–1850. Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 27 (1) (165), 163–214, pp. 167–168. Retrieved from JSTOR via eResources website. ↩

-

Carl Alexander Gibson-Hill records that the name “Cyrene’s Reef” first appeared in a map by Captain Daniel Ross in 1830. In Greek mythology, Cyrene was a nymph who was a fierce huntress and gave her name to a city in Libya. ↩

-

Untitled. (1848, November 2). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1835–1869), p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Dennys, N.B. (1894). Descriptive dictionary of British Malaya (p. 99). London: London and China Telegraph. Retrieved from BooKSG. ↩

-

Legislative Council. (1902, December 13). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Gibson-Hill, C.A. (1957, December). Singapore Old Strait & New Harbour, 1300–1870. Memoirs of the Raffles Museum, 3, p.167. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.51 BOG) ↩

-

Gibson-Hill, May 1954, pp. 168–185. ↩

-

Haughton, 1889, p. 79 ↩

-

St. John’s Island. (1923, April 2). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (1884–1942), p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

St John’s Island. (1935, June 1). The Straits Times, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Island Nation Project. (2015–2016). From one island to another. Retrieved from Island Nation Project website. (Note: The “Island Nation” exhibition was held at the National Library Building from 2–27 June 2015.) ↩

-

Reef will become holiday island by October. (1976, August 27). New Nation, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore. Parliament. Official reports – Parliamentary debates (Hansard). (1996, October 28). Reclamation (Southern Islands). (Vol 66, col. 840). Retrieved from Parliament of Singapore website. ↩

-

Targeting nature lovers and the well-heeled. (2006, December 1). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

N. Sivasothi. (2005, June). The legacy of Pulau Seringat. Raffles Museum Newsletter, 4, 3. (Call no.: RSING 069.095957 RMN) ↩

-

N. Sivasothi. (2002, April). Chek Jawa, Pulau Ubin: From research to education. ALUMNUS. Retrieved from National University of Singapore website. ↩

-

It should be noted that Chek Jawa, along with Pulau Hantu and the Pempang reefs, is still earmarked for possible eventual reclamation in Singapore’s 2013 land-use Master Plan. See What shores will Singapore lose in 7-million population plan? (2013, January 31). Retrieved from Wild Shores of Singapore website. ↩

-

Goh, J. (2010). About us [Web blog]. Retrieved from The Hantu Bloggers website. ↩

-

Ng, M.F.C. (2009). Habitats in harmony: The story of Semakau Landfill. Singapore: National Environment Agency. (Call no.: RSING 333.95095957 NG) ↩

-

Until the 1970s, the sea lapped the edges of familiar places such as East Coast Road, Beach Road, Katong, Bedok, the Esplanade and Collyer Quay, before the creation of districts such as Marina Bay and Marine Parade. ↩

-

For a recent musing on exploring local reefs, see Torame, J. (2016). Notes on some outlying reefs and islands of Singapore. Mynah Magazine, 1. Retrieved from Indiegogo website. ↩