Warrior Women: The Rani of Jhansi Regiment

A band of extraordinary women rose above oppression and poverty in Malayan plantations to overthrow the British in colonial India. Meira Chand has the story.

The traditional Indian woman is invariably portrayed as modest and compliant, entirely focused on her role as daughter, wife and mother. Yet, by the same token, the image of the warrior woman is a recurring figure in Indian history, beginning in Hindu religious mythology with the goddess Durga and culminating in modern times with figures such as Phoolan Devi, the notorious bandit queen.

Female power has also been startlingly celebrated over the centuries in the works of Indian women poets and writers, and in tales of legendary women such as Chand Bibi and the Rani of Jhansi.

The Indian women who joined the Indian National Army (INA) in 1942, as the events of World War II unfolded, chose to recognise their power and agency as women in a way that reflects that alternative image. The bravery of these women in the nationalist efforts to overthrow the British in colonial India has been largely overlooked by history. The issue of gender, and the illiteracy and low caste of the majority of the Indian women allowed for their easy dismissal, and has resulted in their courage being little known or celebrated.

In trying to make sense of the historical meaning and importance of the Rani of Jhansi Regiment while researching my novel, Sacred Waters, I found a general scarcity of material about the women who made up this regiment. In contrast, there is a large collection of material available for those researching the male segment of the INA.

The remarkable story of these brave women deserves to be better known. But it is impossible to write about the Rani of Jhansi Regiment without mentioning the force they were part of, the INA, and its inextricable ties to the charismatic Indian freedom fighter, Subhas Chandra Bose.

Subhas Chandra Bose

The name of Subhas Chandra Bose is little heard today, but in his own time Bose was a hero to many in India. He was a controversial and divisive figure, inspiring aversion in his opponents and adulation in his followers. Both Mahatma Gandhi (1869–1948) and Bose (1897–1945) were legendary sons of India, fighters for freedom from colonial rule, and active during the same time frame. Yet, the means by which each man sought to achieve India’s freedom could not have been more different.

Bose was 28 years younger than Gandhi, and was initially greatly influenced by the writings and ideals of the older man. However, a growing admiration for militant European fascism caused Bose’s views to take a radical turn. He grew critical of Gandhi with his symbolically rustic spinning wheel and call for non-violent civil disobedience, feeling that such passivity would never achieve independence for India. Bose believed freedom could only be gained by violent means, through an invasion of the country from outside. “Give me your blood, and I will give you freedom” was his famous battle cry.

In 1941, Bose escaped house arrest by the British in Calcutta, and fled overland to Germany to petition Adolf Hitler’s help in his mission. At first Hitler was supportive of Bose, allowing him to raise a small army, the Indian Legion, which was comprised of Indian prisoners-of war in Germany who had been captured from the British. Around this time Bose acquired the title, Netaji, or great leader, by which he is still remembered today. Although Hitler appeared supportive of Bose, once Germany lost the war to Russia, it was clear he was in no position to help Bose drive the British out of India. Any interest Hitler retained in Bose was reserved for propaganda victories rather than military ones, and Bose grew progressively disillusioned.

On the other side of the world, the British stronghold of Singapore fell to the Japanese military on 15 February 1942. As had been the case in Germany, large numbers of Indian soldiers who were part of the defeated British army were taken prisoner and encouraged by the Japanese to become part of a new military force known as the Indian National Army.

With Japanese support, this force was expected to rally opposition to British colonial rule in India, and spearhead a possible subsequent Japanese invasion of the country. The fledgling INA unit, however, fell apart in 1943 when its commander, Captain Mohan Singh, was arrested for insubordination to the Japanese. A new leader was sought and the Japanese settled on Subhas Chandra Bose. In Germany, World War II was not going well for Hitler, and he was only too happy to put Bose on a German submarine and pack him off to the Japanese in Singapore.

Bose arrived in Singapore on 2 July 1943 to an enthusiastic welcome from the Indian community. He immediately took command of both the Indian Independence League (IIL), a political organisation of expatriate Indians, and the INA. The latter was made up of approximately 40,000 Indian soldiers, and one of Bose’s first initiatives was to encourage civilian recruits to join this army.

Beginnings of the Jhansi Regiment

Bose was from Bengal, a state that more than any other in India encouraged the education and emancipation of women. It was this principle that led him to create a regiment of women in the INA. The new regiment was formed on 12 July 1943 and Bose named it after the legendary Rani of Jhansi, who famously rode into battle against the British in 1858, and died a martyr to the Indian cause.

Reported numbers vary, but it is thought that the Rani of Jhansi Regiment consisted of well over 1,000 Indian women, spread out over camps in Singapore, Malaya and Burma (Myanmar). It is estimated that only 20 percent of the recruits were well educated women, who became the commanding officers. The remaining 80 percent were the wives and daughters of Tamil labourers who worked on the rubber estates of Malaya, and who would have been either illiterate, or have had no more than a few years of basic education.

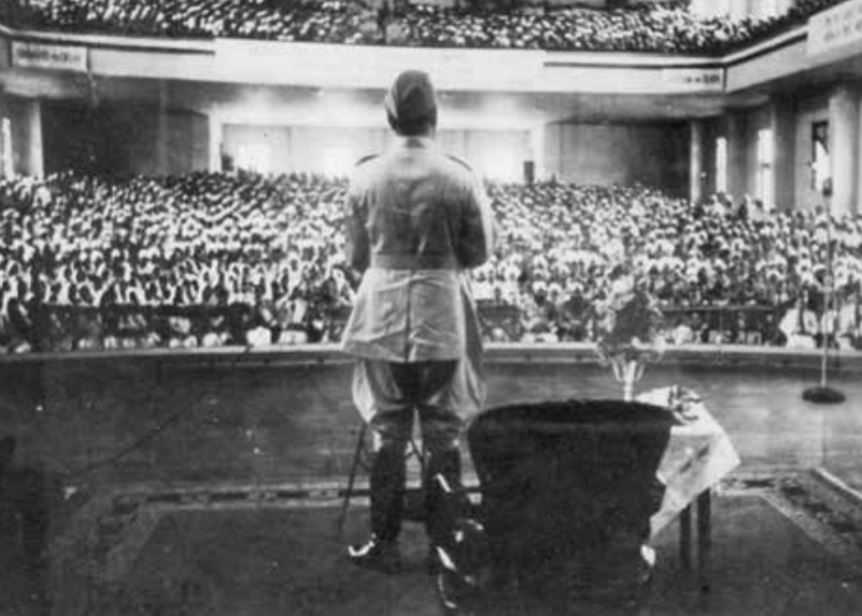

Before large and enthusiastic rallies on the Padang and at Farrer Park, Bose set out his vision for India, and his wish that the Indian women of Singapore, Malaya and Burma – like their contemporaries in the Indian motherland – participate in the freedom movement too.

“This must be a truly revolutionary army… I am appealing also to women… women must be prepared to fight for their freedom and for independence… along with independence they will get their own emancipation.”1

Bose’s inspiring words caused women listening to him on the Padang to surge forward through police barricades, eager to fight as he demanded, for India and their own emancipation.

At the time in India, the struggle for independence from British rule, more than any other impetus, encouraged women from all strata of Indian society to take greater control of their lives. They were urged to participate in a life outside the home in new but sanctioned ways, to cross the forbidden threshold into the world of men, and to work together with men for the freedom of the motherland.

The wave of Indian nationalism sweeping through the Indian diaspora at this time cannot be underestimated. On the British-owned rubber plantations of Malaya, where Tamil workers lived a degraded life set apart from other communities, they would have been well aware of the growing anti-colonial sentiments of the time. Tamil newspapers and radio carried news from India, and pictures of Gandhi hung in many places.

At the very bottom of the plantation hierarchy, Tamil workers lived in poverty and exploitation, but this separateness allowed their Indian identity to remain intact. Even if cut off from India for two or three generations, they still spoke their native tongue and wore Indian dress in everyday life. At Hindu temples in the rubber estates, they celebrated religious festivals and practices. Hindu myth and folklore was handed down from one generation to the next, and their sense of Tamil identity remained strong.2

Stripped of their self-worth in Malaya, the motherland became a consoling image for these displaced Tamils, an India of the imagination, created out of an ancestral memory that was constantly kept alive.3 Seen through this lens – the insularity of the Tamil community and its powerful ties to India and Indian heritage – it is easier to understand why second and third generation Indians in Malaya, who had never lived in India, were stirred by the nationalistic feelings of the time, and willingly laid down their lives for the patriotic cause.

The women who volunteered to join the newly formed Rani of Jhansi Regiment were all exceptionally young, the majority in their mid- to late teens, a few are even documented as being no more than 12 or 14 years old. Most were of an impressionable age, filled with burgeoning emotions, desires and romantic dreams. In the turmoil of war, the women regiment may also have been seen by some as a safe haven where food, shelter and safety from marauding Japanese soldiers was provided.

Even so, it is astounding that Indian women, some so young as to be barely out of childhood, many illiterate and the majority mindful of their traditional roles in their society, should be prepared to leave families and husbands behind and lay down their lives for the cause of Indian freedom. Their commitment is even more exceptional when it is remembered that most had never set foot in their motherland. Yet, all were filled with passion for the cause, all empowered by the irresistible sense of adventure the Rani of Jhansi Regiment offered. Many were also a testament to Bose’s personality as being a powerful element in their decision to join the regiment.

Under Bose’s leadership, Indian women from Singapore, Burma and Malaya, of varied caste, religion and social backgrounds, were recruited into the Rani of Jhansi Regiment to fight for India’s freedom. In caste- and class-ridden India where Hindu will not eat with Muslim, where the superior Brahmin will not mix with the low-caste labourer, where a northerner cannot speak the language of a southerner, and where the untouchable is anathema to all, the fostering of a sense of oneness was a difficult task.

Bose ordered all recruits to eat and live together whatever their differences. As they came from different parts of India and spoke different languages, they were required to learn the common language of Hindustani as a means of communication. Bose also introduced the Roman script for writing Hindustani in order to overcome the conflict of using multiple regional Indian scripts.

Those Ranis whose testimony has been recorded all bear witness to how quickly feelings of differences fell by the wayside, and how the tight knit bonds of being a community of women motivated by a powerful cause overrode everything else. This sense of community forged alliances and collaborations across diverse boundaries, firing up everyone with the commitment of female comradeship and the commonality of shared experiences.

The Making of Women Warriors

The women in the Rani of Jhansi Regiment received the same basic military training as male INA recruits. For many, the early experiences of military life would have been a difficult rite of passage. When the women first joined the regiment, the unshackling of traditional ways could not have been easy, especially for uneducated girls from the plantations.

The discarding of conventional feminine reticence, ingrained through centuries of Indian custom, and the learning of military aggression was akin to building a new personality. The wearing of military uniforms – shorts, jodhpurs, fitted shirts and belts that cinched the waist – revealed the body in an unaccustomed way that may have been shameful for some of the girls.

A fighting force, ready for war, has no time for vanity, and the shedding of their long tresses, a source of pride for all Indian women, must have also been painful to many. Yet, most of the women quickly adapted to the empowerment their new life brought, and the demand for growth it made on their character. In their new role they were soldiers first before they were women.

Although for educated recruits, the Rani of Jhansi Regiment presented an opportunity to assert their identity as women and as Indians, for the illiterate it was above all a chance to gain self-respect for the first time, to escape the abuse and contempt they experienced on a daily basis on the plantations. For many, this change of status had an enormous psychological effect. In her memoir, A Revolutionary Life (1997),4 Lakshmi Sahgal (see text box below), a doctor in Singapore who rose to command the Rani of Jhansi Regiment, points out that while on the plantations the women were treated like cattle and sexually exploited, in the Rani of Jhansi Regiment they found dignity as individuals and pride in fighting for the nation.

For better or for worse, the Rani of Jhansi Regiment was never sent to the frontlines. After their military training, many recruits opted to become nurses and work in hospitals near war zones in Burma, but a large number of women remained as active reservists, always waiting – and expecting – to be sent to the front.

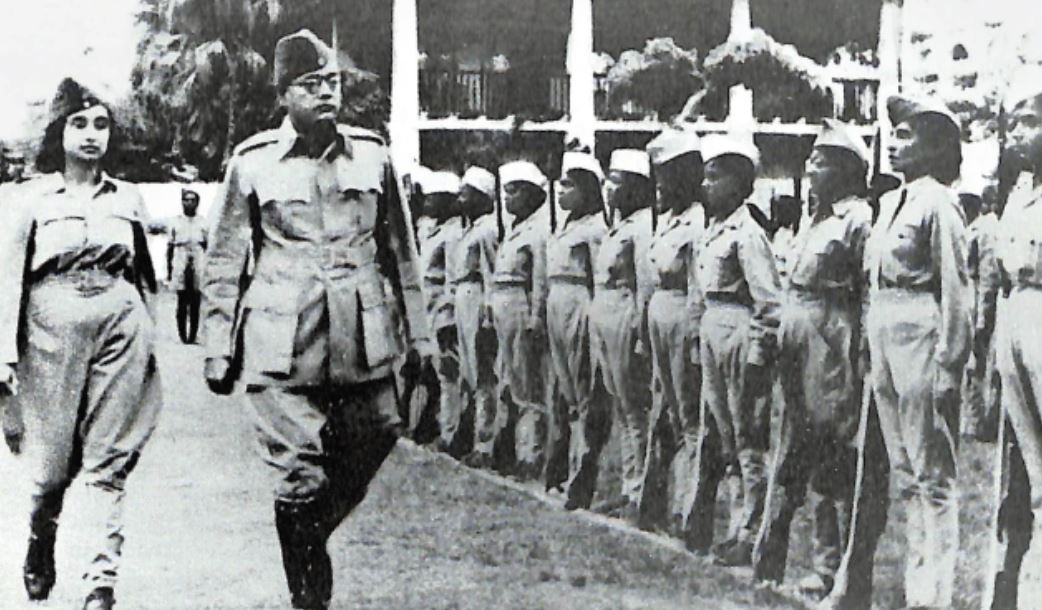

(Right) Soldiers of the Rani of Jhansi Regiment undergoing training, c.1943–45. Image source: Bose, S.K., & Sinha, B.N. (Eds). (1979). Netaji: A Pictorial Biography (p. 176). Calcutta: Ananda Publishers Pte Ltd. (Call no.: R 954.0350924 NET).

Soon after World War II ended, a diary was published in India asserting that some of the women in the Jhansi Regiment did see actual action in the field. Jai Hind: The Diary of a Rebel Daughter of India with the Rani of Jhansi Regiment created a great stir when it was anonymously published in 1945, but it was later found to be a fictionalised account written by a male journalist, A.D. Shenth.

Those ageing Ranis I interviewed for my novel, so many decades after the war, still spoke of Subhas Chandra Bose with intense emotion. Indeed, the influence of Bose’s personal charisma pervades almost everything that has been written about him. Perhaps it is permissible therefore to speculate that many of the Ranis, along with the motivation of patriotism in joining the regiment, may have found in Bose the romantic ideal that traditional Indian society – along with arranged marriage and female repression – denied them.

No tales of impropriety have ever come to light in Bose’s leadership of these young women; he was known to be a dedicated, caring and paternalistic leader. In the minds of the Ranis, they were his Ranis, and Bose spoke of them as my girls. Bose himself openly acknowledged the “grave responsibility” of persuading young women to leave their homes and take up arms.5

The End of World War II

The devastation wreaked by the dropping of the atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki by American warplanes in the first weeks of August 1945 set off a series of events that brought World War II to a rapid close. When the British returned to Malaya in September, Bose kept good his promise to the young women under his command by returning them safely to their families. Within days of the conclusion of the war, Bose himself was killed in a plane crash in Taiwan as he tried to escape to Russia or Manchuria. His death still remains shrouded in mystery and speculation, and has attained the status of myth. Many questions remain unanswered, queries that only time and the release of still-classified documents in India will put to rest.

Bose’s tragic death came as a shock to all who knew him, and history continues to evaluate his contribution to India’s independence in 1947. Yet, history has never dealt squarely with the women of the Rani of Jhansi Regiment, and their courage has been inadequately celebrated. Their gender prevented them from being taken seriously, and indeed the Japanese military was resolutely dismissive of them.

At the end of the war when the INA was dissolved, most of the women were still very young, with their entire lives ahead of them. On their return to Malaya, they were quickly released, rejected by the returning British Military Administration as misguided females carried away by romantic notions. In contrast, the professional male soldiers of the INA were sent to stand trial at the Red Fort in Delhi, where it was expected they would be hung as traitors. The Red Fort Trials, however, collapsed under the pressure of Indian unrest, but that, as they say, is another story.

Many educated women from the officer class of the Rani of Jhansi Regiment later entered professional careers, and much of what we know about the regiment today is largely because of this group of women and the more public nature of their activities. Unfortunately, the majority of women in the rank-and-file regiment returned to the same disempowered situations they had left behind when they first signed up; they married and raised families, and became cloistered again in traditional social structures.

Still others were repatriated to India, a country unfamiliar to them, and died there in poverty and obscurity. Some ex-officers of the Jhansi Regiment worked to secure pensions from the Indian government for these women, but often to no avail.6 Illiteracy prevented many women from being aware of their elevated status as freedom fighters, or that pensions could be extracted from the Indian government because of their status. Their low social position, and lack of knowledge and education made it easy for the Indian government to refuse such pension payouts.7

Yet, without exception, those Ranis I interviewed or those whose recorded testimonies I have read or listened to, all remember their service in the regiment – whatever the dangers and privations they endured – as the best time of their lives.

It is sad that the endeavours of these brave women have been largely forgotten by history. In her introduction to Lakshmi Sahgal’s memoir, A Revolutionary Life, Geraldine Forbes suggests it is easy to reject their enterprise because they never saw action, were never real “female warriors” fighting alongside their men, nor “true women” fighting to death to save their children. Most male-authored accounts of the INA seldom give due reference to the role played by the women in the Rani of Jhansi Regiment. Forbes laments that so many decades after the war when many historians are committed to a more inclusive view of events, this lack of acknowledgement is regrettable.8

The Rani of Jhansi Regiment comprised a relatively small number of women, and they were operative for only the last two years of the war, between 1943 and1945, when Bose commanded the INA. It matters not that this female regiment played a minor role in both the INA and the events of World War II. It matters not that this force of women was small and did not see action at the frontlines. That such a force should have been established at all in that day and age in history is in itself of tremendous importance.

Bose’s motivations for starting the regiment can be endlessly argued, but what matters is that it utterly transformed the lives of the traditional women who joined it. These women entered a scenario where the patriarchal code was at its most inflexible, and where they represented an embodiment of female agency and resistance.

Although so many of the Jhansi Ranis returned to their traditional societies after the war, and others lived out their lives in poverty in India, their brief experience of empowerment would have been orally related to their daughters and other female members of their households, and would have helped sow the seed for change in later generations of women.

In India, recent renewed interest in the Rani of Jhansi Regiment has rekindled discussion of their role in the struggle for Indian independence. It is hoped that with this renewed interest, acknowledgement will at last be given to this small band of extraordinary Indian women.

As the daughter of politically active parents, Lakshmi Sahgal (born Lakshmi Swaminathan; 1914–2012) was made aware, from a young age, of anti-British sentiments in India and the fight for political freedom. After completing high school, she chose to study medicine and obtained her medical degree in 1938.

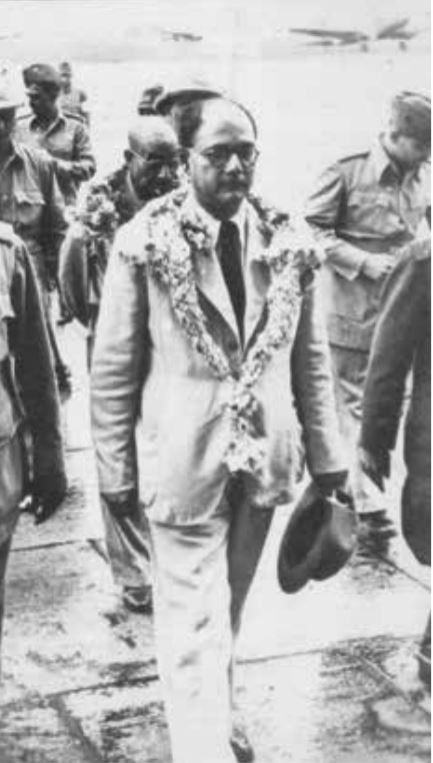

Fiercely independent, Sahgal left an unhappy marriage to follow a lover, who was also a doctor, to Singapore in 1940. During the Japanese Occupation, she became involved with the Indian Independence League. In 1943, Subhas Chandra Bose arrived in Singapore to take command of the INA, and Sahgal, as a prominent woman activist, was part of the official reception committee that met him at the airport.

When Bose announced his wish to create the Rani of Jhansi Regiment, Sahgal was quickly drawn into the organising of this new force. At Bose’s request she took up its command, establishing a camp and recruiting young women to the force. Sahgal became known as Captain Lakshmi, a name and identity that would remain with her for life.

Dr Lakshmi Sahgal took up command of the Rani of Jhansi Regiment and became known as Captain Lakshmi, a name and identity that would remain with her for life. Image source: IASPaper.net.

Dr Lakshmi Sahgal took up command of the Rani of Jhansi Regiment and became known as Captain Lakshmi, a name and identity that would remain with her for life. Image source: IASPaper.net.

In Singapore, in October 1943, Bose formed the Provisional Government of Free India, or as it was more simply known, Azad Hind, and Sahgal was included in his cabinet. Later, in Burma, she established more camps and organised relief work. When the war ended in 1945, Sahgal was taken prisoner by guerrilla fighters, and made to march through the jungle for days. In 1946, she was handed over to the British in Rangoon, and subsequently repatriated to India and released.

In 1947, Sahgal married Prem Kumar Sahgal, a former officer who left the British Indian Army to join the Indian National Army (INA). Along with other fellow INA officers, her husband was put on trial for treason at the Red Fort in Delhi. However, the charge was not upheld, and he was dismissed from the British Indian Army. The couple then settled in Kanpur in the state of Uttar Pradesh, where Sahgal established her medical practice.

In her later years, Sahgal joined the Communist Party of India (Marxist) and was a founding member of the All India Democratic Women’s Association. She passed away on 23 July 2012, at age 97.

Meira Chand’s new novel, Sacred Waters (2017), is published by Marshall Cavendish Editions and retails for S$21.50 at major bookshops. It is also available for reference and loan at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and selected public libraries (Call nos.: RSING 823.914 CHA and SING CHA).

Meira Chand’s multi-cultural heritage is reflected in the nine novels she has published. A Different Sky, set in Singapore, was long-listed for the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award in 2012, and made it to Oprah Winfrey’s reading list. Her new book, Sacred Waters, was recently published in Singapore. She has a PhD in Creative Writing.

Meira Chand’s multi-cultural heritage is reflected in the nine novels she has published. A Different Sky, set in Singapore, was long-listed for the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award in 2012, and made it to Oprah Winfrey’s reading list. Her new book, Sacred Waters, was recently published in Singapore. She has a PhD in Creative Writing.

REFERENCES

Jai Hind: The diary of a rebel daughter of India, with the Rani of Jhansi Regiment. (1945). Bombay: Janmabhoomi Prakashan Mandir. (Call no.: RSEA 954.025 JAI).

Lebra, J.C. (2008). The Indian National Army and Japan (p. 61). Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSING 940.5354 LEB-[WAR]).

NOTES

-

Lee, G. B. (2005). The Syonan years: Singapore under Japanese rule 1942–1945 (p. 237). Singapore: National Archives of Singapore and Epigram. (Call no.: RSING q940.53957 LEE-[WAR]). ↩

-

Lebra, J.C. (2008). The Indian National Army and Japan (p. 61). Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSING 940.5354 LEB-[WAR]). ↩

-

Pillai, S., & Subramaniam, G. (2009). Through the coils of memory and ethnicity: The Malaysian Indian journey to nationhood. European Journal of Social Sciences, 7 (3), 133–148, p. 139. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Sahgal, L. (1997). A revolutionary life: Memoirs of an activist. New Delhi: Kali for Women. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Hills, C., & Silverman, D.C. (October, 1993). Nationalism and feminism in late colonial India: The Rani of Jhansi Regiment, 1943–1945. Modern Asian Studies, 27 (4), 741–760, p. 748. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Gawankar, R. (2003). The women’s regiment and Capt. Lakshmi of INA: An untold episode of NRI women’s contribution to Indian freedom struggle (pp. 263–264). New Delhi: Devika Publications. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Sahgal, 1997, p. xxix. ↩