Globetrotting Mums: Then and Now

Bonny Tan interweaves her own experiences as a modern Singaporean mother travelling and living abroad with those of two Victorian-era Englishwomen.

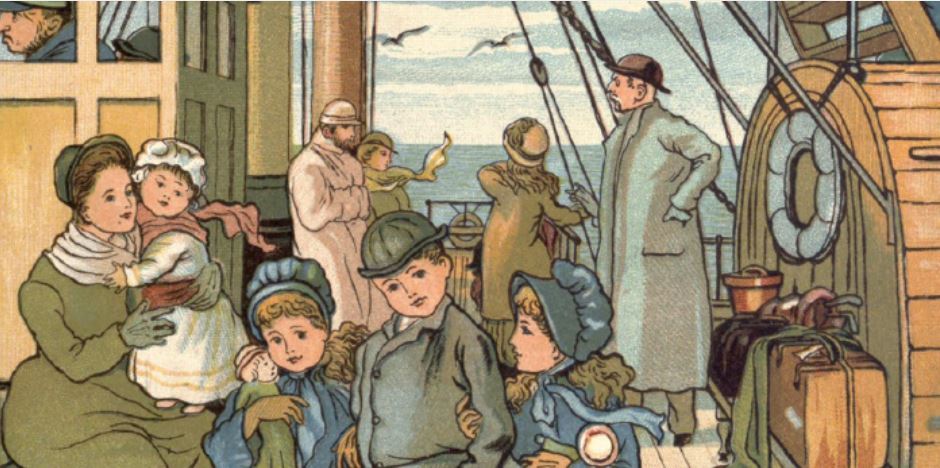

My son, all of six months old, months old, was on his first flight out of Singapore, ensconced in a bassinet that hung precariously in front of me. With my backpack holding both laptop and milk bottles stashed in the overhead compartment, I wondered how this journey and new living arrangement – of commuting for work between two countries with a child in tow – would pan out. Peering out of the window into the vast blue sea beneath, it struck me that for centuries, mothers and their children have made such journeys for various reasons and under more harrowing circumstances – many of whom never lived long enough to return home.

A Mother’s Perspective

Many of the early 19th-century travel accounts were written by men – mostly commissioned by their government, a scientific institution or a royal benefactor. Their descriptions were invariably functional, with a bias towards trade, land acquisition or research, rather than personal in nature. While adventurous women such as Isabella Bird would later gain fame for their travel writing, many were usually single and explored the world sans husband and children.

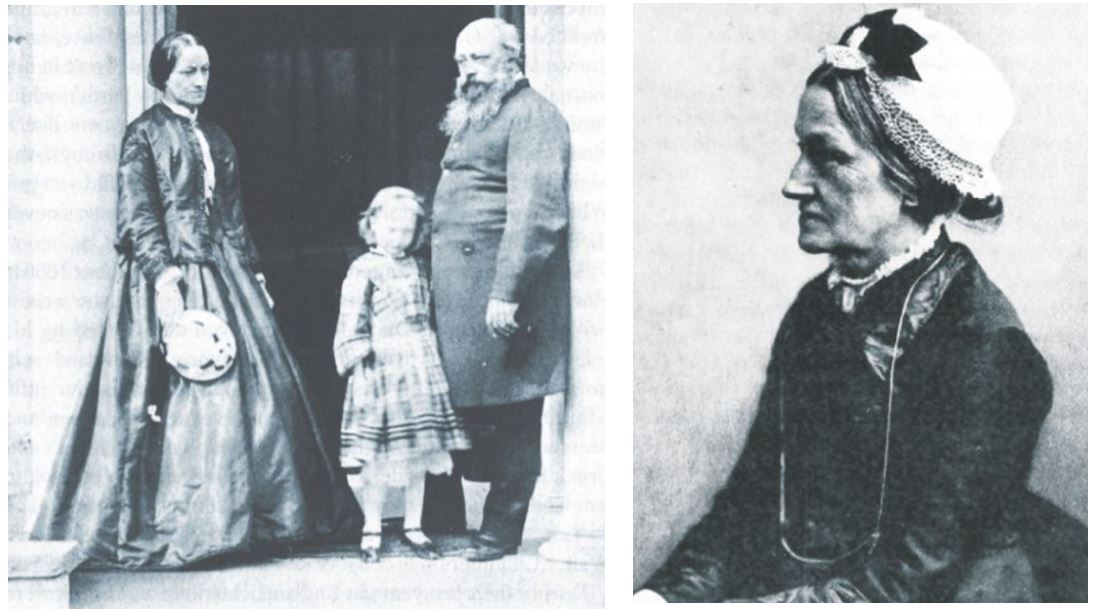

Published accounts of mothers in the 19th century who travelled to new lands with their families are rare. Harriette McDougall and Anna “Annie” Brassey were two such Victorian-era mothers who penned their adventures abroad with their children. Their circumstances, however, could not have been more different.

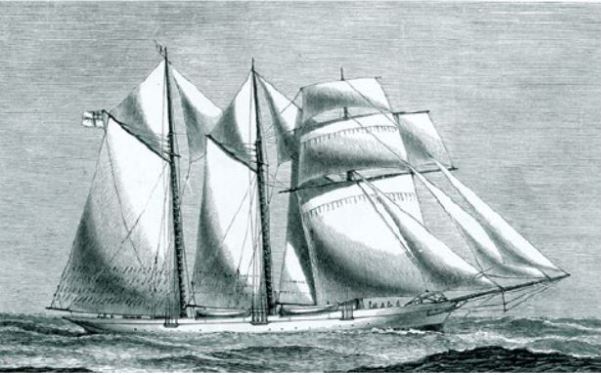

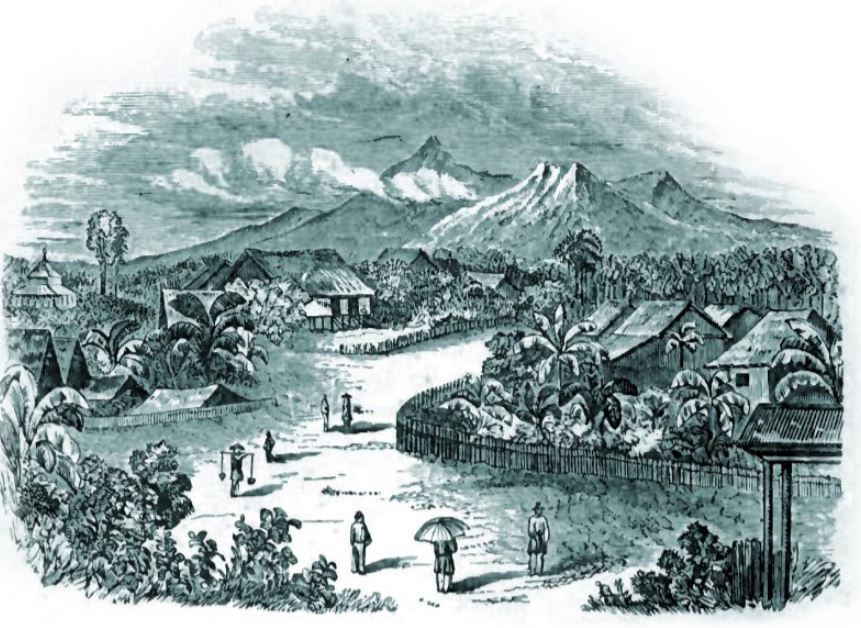

While Harriette set up home with her family – living among the local people – in the disease-ridden jungles of Sarawak in 1847, Annie travelled with her family in relative comfort on board a private schooner, the Sunbeam, calling in at various ports around the world. Annie’s well-documented journey began in 1876, almost three decades after Harriette’s sojourn.

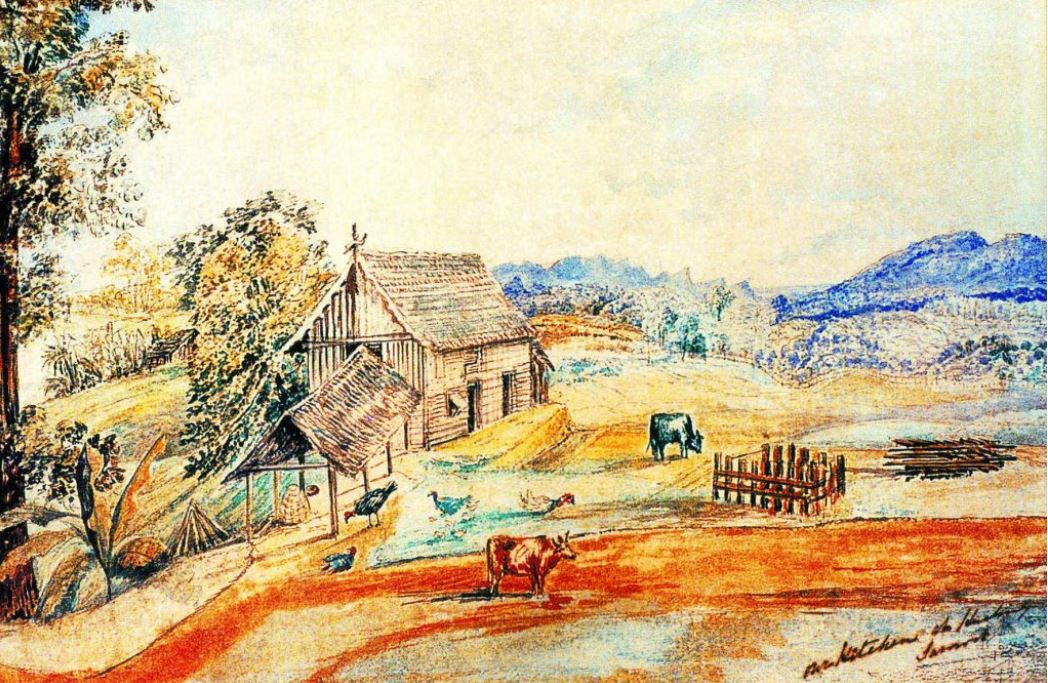

Harriette was married to Francis Thomas McDougall, who would later become the first Bishop of Sarawak. They initially served as missionaries among head-hunters, pirates and rioting Chinese between 1847 and 1867. Her life of hardship in the tropics is captured through three books: Letters from Sarawak: Addressed to a Child1 (1854), which contains letters to her eldest son; her autobiography, Sketches of Our Life at Sarawak2 (1882); and her husband’s biography, Memoirs of Francis Thomas McDougall… Sometime Bishop of Labuan and Sarawak, and of Harriette, his Wife3 (1889).

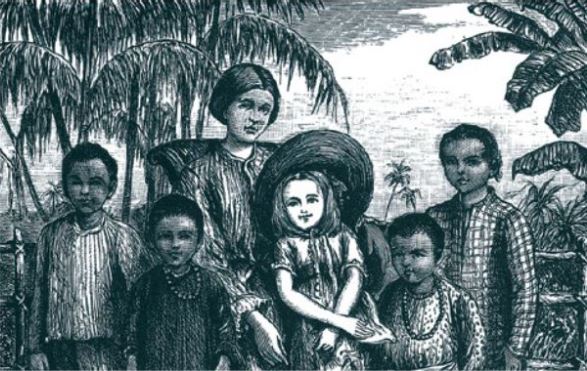

At aged 29, Harriette left the comforts of England for Sarawak in 1847 with her husband and baby son Harry, leaving behind Charles, her firstborn. She would later lay Harry to rest in Singapore when he was only three, and also lost several other children in infancy. Those who survived were raised together with orphans of various origins – Chinese, Dyaks (or Dayaks) as well as the offspring of mixed parentage – whom she and her husband had adopted.

Harriette lived in Sarawak for almost 20 years, returning to England several times in between and, in particular, between 1860 and 1862 to settle her older children at school, before returning to Sarawak with her youngest child.

Annie Brassey was born into a privileged family. She married Thomas Brassey, the son of a railway industrialist at age 21 in 1860, and when her husband turned to politics, Annie dutifully supported him in his work. He was later knighted and, in 1886, elevated to the peerage as Baron Brassey. The couple maintained a firm friendship with then British Prime Minister William Gladstone. Such connections likely helped smoothen their journeys to places like the Middle East, North America and parts of Europe and subsequently their tour of the world.

Annie’s well-known account – A Voyage in the ‘Sunbeam’: Our Home on the Ocean for Eleven Months4 – was published in 1878, barely two years after she departed in July 1876 on a world tour with her husband, four children, pet pugs and a crew of 30 men. Illustrated with drawings based on her photographs and descriptions, the book became so enormously popular that it was republished in various languages and in 19 editions altogether.

Unlike the women of her generation, Annie’s 1876 circumnavigation of the world was not borne out of an obligation to accompany her husband for his work but was something she herself had longed to do. The book was an outcome of “her painstaking desire not only to see everything thoroughly but to record her impressions faithfully and accurately”,5 as her husband writes in the preface. This became one of many such family travels she would embark on and write about thereafter, ending only with her death from malaria in 1887 while on her final journey.

A Mother’s Stoicism

The chance to be exposed to new sights, flavours and experiences is what attracts most people to venture abroad and settle in a new country. Life away from the comforts of home, however, calls for a certain amount of resilience and adaptability as well as a sense of fun, without which the inevitable culture shock can often bring the adventure to an abrupt end.

Harriette describes how a family unprepared for such changes could not last the long haul. She gives an account of a certain doctor, Mr C, who had moved to Sarawak with his family. He had ignored her advice to leave the older children in England but persisted in coming as a “party of nine, having lost one child in Singapore”. They did not last beyond a month because Mrs C was “so disgusted with the place”, complaining there were “no shops, no amusements, always hot weather, and food so dear!”6

During our first week in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnamese friends were eager to introduce us to their unique cuisine. Game to try new things, we were brought to a nondescript local eatery. It looked familiar, like a noisy coffeeshop from home. So we felt safe – until a large live lizard was dangled before us and we were told that it would be our lunch! Out of courtesy, the locals often try to cater to the taste buds of visitors, but often, the most prized food item on the table could be culturally discomfiting for a foreigner.

Harriette describes such an occasion when they were treated to a Dyak feast:

“As we English folks could not eat fowls roasted in their feathers, nor cakes fried in cocoa-nut oil, they brought us fine joints of bamboo filled with pulut rice, which turns to a jelly in cooking and is fragrant with the scent of the young cane. I was going to eat this delicacy when my eyes fell upon three human heads standing on a large dish, freshly killed and slightly smoked, with food and sirih leaves in their mouths… But I dared say nothing. These Dyaks had killed our enemies, and were only following their own customs by rejoicing over their dead victims.”7

Food supply onboard the Sunbeam had its fair share of problems. Annie describes how their livestock, namely six sheep, 60 chickens, 30 ducks and four dozen pigeons, were depleted by the carelessness of the sailors. Fortunately, some spare tins of food stored under the floor of the nursery helped sustain them until the next port of call.

The incident led Annie to reflect on the difficulties of travel in the days when tinned food and steam power did not exist:

“We often wonder how the earlier navigators got on, when there were no such things as tinned provisions, and when the facilities for carrying water were of the poorest description, while they were often months and months at sea, without an opportunity of replenishing their stores, and with no steam-power to fall back upon in case they were becalmed.”8

In much the same way, I’ve wondered how travelling mothers in the Victorian era kept their sanity intact and their children occupied during long stretches of boredom and monotony. Without digital toys, streaming TV and movies, and social media to keep in contact with friends and family across the oceans, how did these mothers cope?

For one, both Harriette’s and Annie’s families owned extensive libraries. Annie had more than 700 books, including several foreign language ones, some of which were gifted to her on her travels. These helped entertain the family through long dull moments. Annie also received various exotic pets from the hosts she called on at various ports, although not all survived the journey.

Besides the usual chores on deck, Annie devised games for the children to play on board. One such pastime was a soldier’s drill where the children marched up and down the deck to the music of a fiddle and the “somewhat discordant noise of their own drums”.

Harriet’s orphan boys adopted English games while continuing to make their own local toys such as kites:

“The children amused themselves as English boys do. There was a season for marbles, for hop-scotch, for tops, and for kites… they cut thin paper into the shapes of birds, fish, or butterflies, and stretch it over thin slips of the spine of the cocoa-nut leaf, then they ornament it with bits of red or blue paper, and fasten it together with a pinch of boiled rice.”9

A Mother’s Travails

Travelling on local forms of transport may seem dangerous to someone who comes from a more developed part of the world. Even so, we opted to commute as the locals do – by scooter. We experienced the harsh rays of the mid-day sun beating down on our backs, the burns from scooter exhaust pipes brushing past our calves, the desperate rush to seek shelter when the skies suddenly opened, or riding knee-deep through muddy river waters and sludge at high tide.

On the flip side, it allowed us to feel the pulse of the city – inhaling the heady aroma of meat being barbecued by the roadside, and chatting with fellow riders while astride on our scooter as if we were nonchalantly walking down a road. So when we had our son Bryan, we travelled with him perched on a rattan chair affixed at the front of our scooter seat.

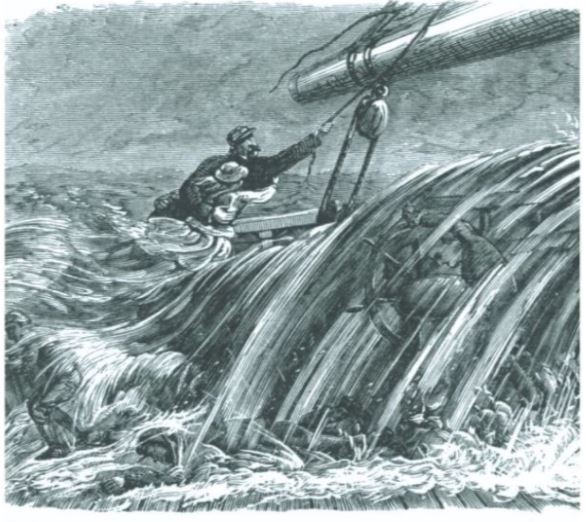

In the 19th century, travel by sea was fraught with danger, not only from the mercurial weather and waves, but also from freak accidents. Several days into the start of Annie’s journey, the Sunbeam sailed into a violent storm and her son Allnutt and daughter Mabelle were almost thrown overboard:

“In a second the sea came pouring over the stern, above Allnutt’s head. The boy was nearly washed overboard, but he managed to catch hold of the rail, and with great presence of mind, stuck his knees into the bulwarks.”10

Meanwhile, the captain, who had instinctively coiled a rope around his own wrist, managed to grab Mabelle even as the waves threatened to sweep both of them overboard. Annie remembers that Mabelle “was perfectly self-possessed, and only said quietly, ‘Hold on, Captain Lecky, hold on!’”11 The evening did not prove restful as they were once more deluged by huge waves. With her bed drenched, Annie spent the night mopping and clearing the mess.

In February 1877, the Brasseys experienced another close call when a fire engulfed the Sunbeam. Flying embers from a little fire stoked in the nursery to keep the room warm sparked off a mini inferno. Annie was awakened in the middle of the night by cries of “Fire! Fire!” Her first thought was the children, but thankfully they had not been forgotten; the nurse had “seized a child under each arm, wrapped them in blankets, and carried them off to the deck-house… The children… never cried nor made the least fuss, but composed themselves”.12

In the meantime, the quick-thinking crew put out the fire before it became uncontrollable with a new-fangled technology of the time – a fire extinguisher. A woman made of less sterner stuff would have buckled and returned home, but Annie was undaunted by these setbacks.

We witnessed the riots of May 2014 that swept through Ho Chi Minh City. The Vietnamese, who had been protesting against Chinese aggression in the Eastern Sea, began attacking businesses in the city that bore Chinese signages. Taiwanese, Singaporean and Malaysian institutions were all at risk. Later, we heard how fellow Singaporeans had escaped from burning factories or saw protestors stake out apartment blocks where they lived. Even so, we chose to stay put as we saw the potential benefits of living in Vietnam.

Well aware of the perils of living in the jungles of Borneo with a young family, Frank McDougall had initially opted for a position at the British Museum. Harriette, however, persuaded the director of the museum to release her husband from his obligation in favour of Sarawak. Frank understood Harriette’s reasons for choosing a location in remote Borneo:

“… she dared not withdraw him from the service to which she thought that God had called him, even though it was to fill a post of danger, which, to many minds might have appeared like that of leading a forlorn hope.”13

Unfortunately, in February 1857, their worst fears were realised when Chinese gold miners set fire to their settlement. In the subsequent bloody massacre, several of their English neighbours saw their children beheaded and spouses speared to death. Harriette and her family escaped the insurrection only because the Chinese needed her husband’s medical expertise. Frank attended to the wounded and told Harriette to escape downriver with the children on a small life-boat to a schooner awaiting them at the river’s mouth.

Later, after being reunited with her husband, they travelled to Linga. Despite the harrowing conditions on board, Harriette felt neither hunger nor anguish because her family was safe:

“The night was very dark and wet, and the deck leaked upon us, so that we and our bags and bundles were soon wet through. But we neither heeded the rain nor felt the cold. We had eaten nothing since early morning, but were not hungry; and although for several nights we could scarcely be said to have slept, we were not sleepy. A deep thankfulness took possession of my soul; all our dear ones were spared to us. My children were in my arms, my husband paced the deck over my head. I seemed to have no cares, and to be able to trust to God for the future, who had been so merciful to us hitherto.”14

A Mother’s Anguish

Contrary to expectations, the expatriate mother does not always lead a glamorous life, especially when she has children. Her days are less likely spent in spas and nail bars than dodging traffic while ferrying children to school or attempting to juggle work with personal time. What is little known are the challenges of a dislocated life, which could range from homesickness and loneliness to the more mundane sense of boredom as one is plucked from a sense of routine.

Harriette recognised these symptoms in both herself and among her countrymen:

“It is, however, a common mistake to imagine that the life of a missionary is an exciting one. On the contrary, its trial lies in its monotony. The uneventful day, mapped out into hours of teaching and study, sleep, exercise and religious duties; the constant society of natives… who do not sympathize with your English ideas; the sameness of the climate, which even precludes discourse about the weather – all this, added to the distance from relations and friends at home, combined with the enervating effects of a hot climate, causes heaviness of spirits and despondency to single men and women.”15

A greater discomfort is the pain of physical separation from loved ones. This could mean leaving aged parents behind, a spouse or even children. The separation may be for weeks or months, but often it is years. The convenience of air-travel and instant communication by email, texting and video chat bridge the separation but can never take the place of extended time with a loved one.

For the Victorian woman with a spouse called to travel, the woman’s first place was with the husband, even at the cost of leaving a child behind. When the McDougalls first departed England for Sarawak on 30 December 1847, Harriette left behind her eldest son Charles, just two years old then, while taking her infant child Harry with them.

It is from Frank’s memoirs rather than Harriette’s that we see the emotional price she paid. “[N]o one can tell the pangs which that parting must have cost her” writes Frank. “Bravely as she had parted from her eldest child, he seems to have been ever in her thoughts, and her heart hungered for news of him.”16

The pain of separation, however, gave birth to the book, Letters from Sarawak; Addressed to a Child, based on the carefully crafted letters she had written to her son, in the hope that this would help him understand their circumstances. She states in the preface:

“All parents whose fate separates them from their little ones, during their early years, must feel anxious to lessen the distance which parts them, by such familiar accounts of their life and habits as shall give their children a vivid interest in their parents’ home.”17

For the child from a well-to-do Victorian family, being sent away to boarding school at a young age was a familiar rite of passage. Early in their travels, while at Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil, Annie’s oldest son, then aged 13, took leave for England to continue his studies.

“We knew the parting had to be made, but this did not lessen our grief: for although it is at all times hard to say good-bye for a long period to those nearest and dearest to you, it is especially so in a foreign land, with the prospect of a long voyage on both sides. Moreover, it is extremely uncertain when we shall hear of our boy’s safe arrival.”18

For Harriette, leaving her older children Mab, Edith and Herbert in England when she returned to Sarawak in 1863 after a two-year absence was a pragmatic decision because she knew that “no English child can thrive in that unchangeable climate after it is six years old”.19 Yet it was not emotionally easy, as she shared with her sister-in-law:

“Dear little ones, they are seldom out of our thoughts. It was very hard to go away this time. I still feel a tightness about my heart, and I cannot endure that people should say to us, ‘Did you leave any children in England? A great trial, is it not?’ I cannot bear to talk of it, but everything reminds me of my darlings’.”20

The Victorian mother, despite medical advancements of the time, often suffered the darkest separation – death.

By August 1851, Harriette had lost five infants across a span of five years, besides having lost her second-born Harry early in her service in 1850 and her firstborn Charles in a freak accident in England in 1854. The losses not only devastated her emotionally but also physically. Yet, she was able to place the losses in the context of an eternal hope – “that it was better to have had them and lost them than never to have had them”. She looked on them as a sacred deposit in the hands of God, to be restored to her hereafter.21

Sickness would continue to plague the family in a hostile environment where cholera and various tropical diseases were rife, along with a poor diet and the stress of physical dangers from hostile tribes. In the end it would be poor health that would bring the McDougalls back to England in 1867 to recuperate and retire.

Although Annie continued her journey with her family to other far-flung outposts after her first book, her final story would end tragically. She died on 14 September 1887 from malarial fever as the family sailed from Australia to Mauritius. Her publication, The Last Voyage to India and Australia in the ‘Sunbeam’,22 would be completed posthumously by her widowed husband and published in 1889.

Bonny Tan is a former Senior Librarian at the National Library, Singapore. She currently resides in Vietnam with her family and is a regular contributor to BiblioAsia magazine.

Bonny Tan is a former Senior Librarian at the National Library, Singapore. She currently resides in Vietnam with her family and is a regular contributor to BiblioAsia magazine.

NOTES

-

McDougall, H. (1854). Letters from Sarawak: Addressed to a child. London: Grant & Griffith. (Call no.: RRARE 991.12 MAC; Microfilm no.: NL25436) ↩

-

McDougall, H. (1882). Sketches of our life at Sarawak. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. (Call no.: RRARE 991.12 MAC; Microfilm no.: NL26013) ↩

-

Bunyon, C.J. (1889). Memoirs of Francis Thomas McDougall, D.C.L.F.R.C.S., sometime bishop of Labuan and Sarawak, and of Harriette, his wife. London: Longmans, Greens, and Co. (Call no.: RRARE 266.0230924 MAC.B; Microfilm no.: NL25423) ↩

-

Brassey, A. (1878). A voyage in the ‘Sunbeam’: Our home on the ocean for eleven months. London: Longmans, Green. (Call no.: RRARE 910.41 BRA; Microfilm no.: NL25750) ↩

-

Brassey, A. (1889). The last voyage to India and Australia in the ‘Sunbeam’. London: Longmans, Green. (Call no.: RRARE 915 BRA; Microfilm no.: NL8059) ↩