Malay Seafarers in Liverpool

Tim Bunnell speaks to former Malay sailors who reside in the English city and learns how they manage to sustain their identity in a city so removed from home.

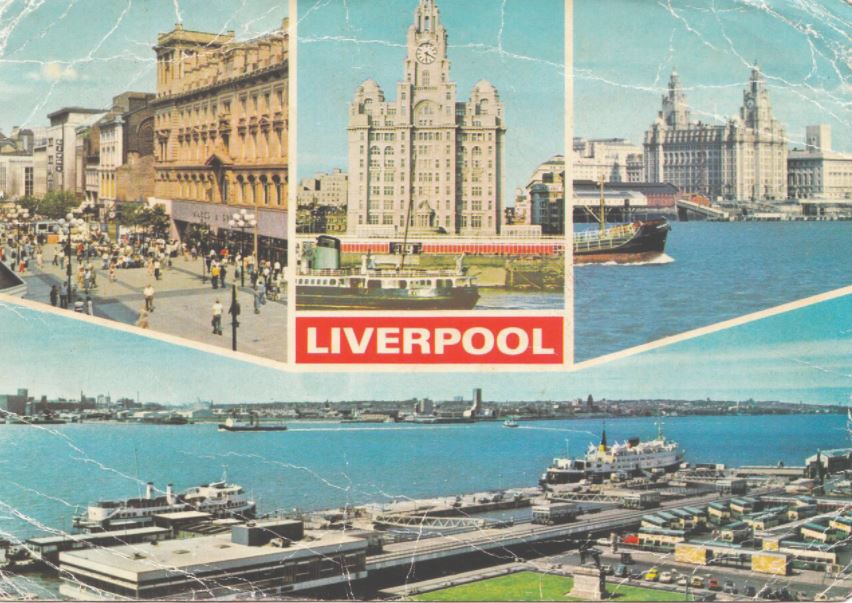

Liverpool saw extremes of both prosperity and decline in a span of just two centuries.1 Between the 18th and early 20th centuries, the British city on the northwestern coast of England, where the River Mersey meets the Irish Sea, was a major global trade and migration port. During the Industrial Revolution that took place from around 1760 to 1840, Liverpool’s role as the main gateway in the West for raw materials and finished goods, along with the ships that called there, were instrumental in developing Britain’s trading links with North and South America, West Africa, the Middle and Far East, and Australia.

At the end of the 19th century, Liverpool’s four major import trades – cotton, sugar, timber and grain – flourished and its dock force alone numbered 30,000.2 But in the last three decades of the 20th century, the one-time “world city” fell into economic decline, and by the early 1980s, unemployment rates in Liverpool were among the highest in the United Kingdom.3

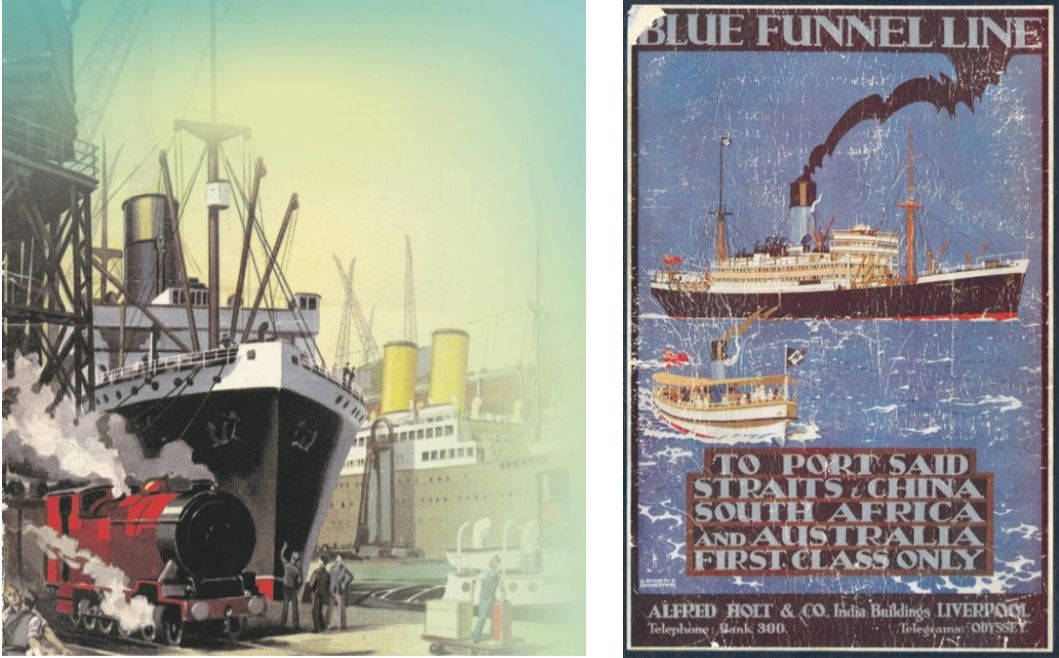

(Right) An advertisement by the Blue Funnel Line promoting its sailings to Port Said, China, the Straits, South Africa and Australia. Between the 1940s and 60s, many Malay men from Southeast Asia worked as seafarers on board vessels owned by the line. Image reproduced from back cover of The Annual of the East. (1930). London: Alabaster, Passmore & Sons. (Accession no.: B02921323K; Microfilm no.: NL257391).

It is against this historical maritime backdrop that my research on Malay seamen in Liverpool takes place. In the mid-20th century, after World War II, men from the dispersed and ethnically diverse Malay world (or alam Melayu) of Southeast Asia worked as seafarers on British-owned and other merchant ships. At the time, Singapore was the hub for shipping networks in the Malay world and a key node in the global oceanic routes. Singapore was also home to the regional headquarters of the Ocean Steamship Company of Liverpool.

Between the 1940s and 60s, some of these Malay sailors settled in port cities in England and America, including London, Cardiff and New York. In Liverpool, most of the newly arrived seamen lived in the south docks area of the city, some eventually marrying British women and forming families. Several also opened their homes as lodging for visiting Malay seamen.

The Golden Age of Malay Liverpool

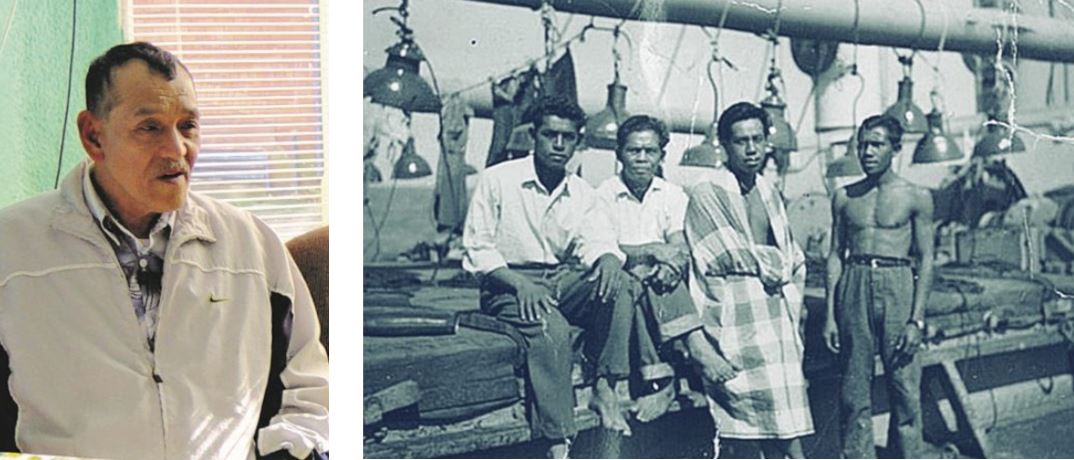

Hailing from Tanjung Keling on the outskirts of Malacca, Mohamed Nor Hamid (Mat Nor) first arrived in Liverpool in 1952 as a crew member on the Cingalese Prince. Soon after arrival, he was able to locate his uncle, Youp bin Baba (Ben Youp), and his family with the help of other Malay seamen residing in Liverpool.

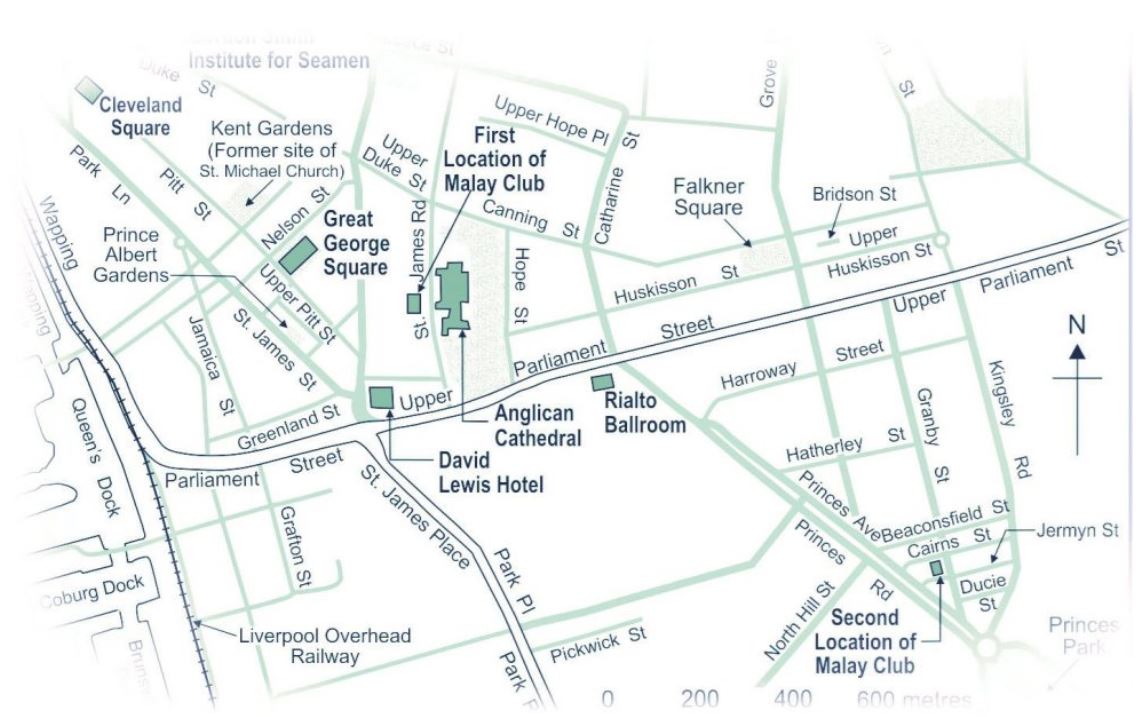

Youp had married a local English woman and settled down at 144 Upper Huskisson Street.4 As it turned out, Youp was away at sea and the guest rooms in his house were occupied by other visiting Malay seamen. Fortunately, Mat Nor was able to find accommodation just next door at No. 142, in the home of fellow Malaccan, Nemit Bin Ayem from Purukalam Tigi, and his English wife Bridgit.

It is not difficult to understand why Malay seamen decided to use Liverpool as their home port in the two decades after World War II. Malays already working on the docks generally looked out for new arrivals from their homeland. Even those who slipped through this net and ended up at the Seamen’s Mission in Canning Place were often directed to 144 Upper Huskisson Street and other houses like it.

There was also no shortage of seafaring work during this time. Historian Jon Murden describes the period as a postwar economic “golden age” during which worldwide demand for Britain’s manufactured goods soared and Liverpool’s port and merchant marine served the rapidly expanding trade.5 This meant that there was a regular in-flow and through-flow of seafarers from British Malaya.

(Right) Mohamed Nor Hamid (Mat Nor) on the far left, on board the Cingalese Prince in 1952 with some of his shipmates. Courtesy of Mohamed Nor Hamid.

Mat Nor reminisces of his life in Liverpool:

“We forget about all the life in Singapore, you know. That’s why most of the Malays stay here because it’s a happy life in Liverpool, very happy, very easy to get a job. Any time you want a ship you can get. They send the telegram to the house you see… sometimes three or four telegram come in a day.”6

The telegrams invited men to the “pool” where they were able to apply for jobs on board ships, subject to passing a medical examination. Given the high demand for seafaring labour, even Malay men who were not British subjects experienced little difficulty in securing work.7

A Malay Club on St James Road

Mat Nor recounted his arrival in Liverpool in 1952: “[F]irst time when I came here, we got no place; Malay people got no place.”8 What he meant was that there was no specifically “Malay place” at which he and his friends could comfortably socialise.

All this changed when the former seafarer Johan Awang, who had moved to Liverpool from New York City after World War II, opened a club for Malay seamen on St James Road in the mid-1950s.9 The Malay Club, as it came to be known, occupied the first floor of a house facing Liverpool’s Anglican Cathedral. By that time, Johan Awang’s own home on 37 Greenland Street – a short walk from St James Road – was already well known to visiting as well as Liverpool-based Malay seamen.

The Malay Club had bunk beds for visiting seamen, a big backyard and a games room with a dartboard. There was also a prayer room on the second floor. Food was central to memories of the club and, more broadly, of Malay Liverpool during that period – the very mention of spicy Malay fare cooked for special occasions and gatherings would transport people whom I interviewed back to St James Road club of the 1950s.

At weekends, seamen took their children and wives to visit what was otherwise largely an adult male space. But the club became more than just a place for the Malay diaspora to meet: it was a place where seafarers, ex-seafarers and, to a lesser extent, their family members could be comfortable within their own skins.

Relocation to No. 7 Jermyn Street

In the 1960s, with the streets southwest of the Anglican Cathedral marked out for post-war redevelopment, a group of Liverpool-based Malay seamen pooled their resources to buy a house at No. 7 Jermyn Street, just off bustling Granby Street, in what is today known as the Liverpool 8 area of the city.

Surviving records reveal that an agreement was signed on 4 June 1963 to purchase the building from a Marjorie Josephine Steele for £1,500. A supplementary trust deed signed in 1974 names Abdul Salem and Bahazin Bin-Kassim10 as the trustees of the property.

Bahazin, who was born in Perak, Malaya, in 1924, became the first president of the club at its new location, and also assumed the all-important role of cook. As had been the case at St James Road, the clubhouse on Jermyn Street included a prayer room. However, Bahazin is remembered as having been less strict than Johan Awang with regard to the activities that could take place in the club.

Food was available during the fasting month of Ramadan, for example, and Bahazin would say that it was “between you and God” whether it was eaten or not. Bahazin bought the house next to the club – No. 5 – and lived there with his English wife. With Malay lodgers staying at both numbers 5 and 7, Jermyn Street became a place in Liverpool where it was always possible to find Malay banter and spicy food.

Overall, this was a happy and optimistic time for the Malay community in Liverpool. The city had become the “capital of the Malay Atlantic”11 and, in some ways, for many Liverpudilians, it felt like the centre of the world. In addition to ambitious municipal plans announced in the 1960s for a hypermodern Liverpool of the 21st century, exciting things were happening in its music scene – this was the birthplace of the wildly popular Beatles – and in the city’s football stadiums.12 The mid-1960s also saw an all-time record tonnage of cargo passing through the port. Jobs were still relatively easy to come by, at sea and onshore, including on the docks where Mat Nor worked.

A Place for Malays

The Malay Club – first at St James Road and then at Jermyn Street – played a significant part in making Liverpool a home away from home for seamen from the alam Melayu who had made the city their seafaring base. Through the Malay Club, visiting seamen were able to plug into the social networks of Liverpool’s small Malay community, which likely never exceeded more than a hundred. The club became the focal point for Malay seafaring visitors, seamen who based themselves in Liverpool, and men who had taken local “shore jobs”.

By the time the club moved to Jermyn Street in 1963, the ex-seamen who met and socialised there also included retired “elder statesmen” such as Ben Youp. Youp later moved into Bahazin’s house next door at 5 Jermyn Street and was a regular at the club in the early 1970s.

The children of Malay ex-seamen – who were born in England and never set foot in Southeast Asia – heard stories about what life was like on the other side of the world from interacting with their fathers’ friends at the club. With these social connections came gifts, gossip and news from home. Interestingly, one of the seamen kept a pet parrot at the club that had been taught to say Malay words such as makan (“eat”) as well as several rude words in English and Malay.

The End of an Era

By the 1960s, the Malay community had established its footing in Liverpool. However, the city’s commercial place in the world economy was undergoing profound change. Although few people realised it then, the Malay Club’s move from St James Road to Jermyn Street in 1963 was made during a time when the postwar golden age of British shipping had already passed.

It is unlikely that the club run by Bahazin on Jermyn Street received as many visiting seamen compared with the earlier location on St James Road – the 1950s, after all, had been a decade of shipping prosperity. Fewer ships arrived in Liverpool in the subsequent decades, bringing fewer new Malay seafarers to sustain the community that had come to call the city home.

In contrast, the number of Malaysian students arriving in Liverpool began to increase. In the 1970s, as part of the aggressive economic development plans pushed by the Malaysian government, hundreds of young Malays were sent to Britain to study. Liverpool was one of the cities that received undergraduate scholarship students, although it never saw the same numbers of Malay (and other Malaysian) students as it had visiting Malay seamen in the previous decades. Even so, the arrival of these students gave the Malay Club a new lease of life.

Abdul Rahim Daud was one of only two Malay students from Malaysia who began studies at Liverpool University in 1970. He recalls that by his final year, the numbers were much greater, but also that he enjoyed visiting ex-seafarers at No. 7 Jermyn Street:

“Last time there’s no internet, phone also, no mobile so say like as if total bye-bye to your parents, to your kampong [home village]. So you feel like homesick so that’s why I used to go very often to the Malay Club so at least see them, meet them, at least I feel a reduced homesick a little bit.”13

By this time, Liverpool was no longer the thriving city and maritime port it once had been. Granby Street, near the Malay Club’s second home in the Liverpool 8 district, had been a busy commercial thoroughfare in the 1960s. In the following decade, however, the area became synonymous with “inner-city” social and economic problems arising in part from Liverpool’s diminished position in the national and international arena. Media coverage of the infamous street disturbances in Liverpool in the 1980s marked the city on national mental maps as the “new Harlem of Liverpool”, and it came to be seen as the epitome of British post-imperial and post-industrial urban decline.

Opportunities for dock work, particularly, were badly affected, with total employment in 1979 being less than half of what it was in 1967. In 1979, it was reported that five or six out of every 10 Malay men in the city were unemployed and receiving social security payments.14 Retrenched from Gladstone Dock in 1978, Mat Nor used some of the redundancy money to pay for a return trip to Malaysia with his Liverpool-born family.

By the late 1980s, the Malay Club had become known as the Malaysia-Singapore Association. In the early 1990s, the club – with Mat Nor as its president – was officially registered as the Merseyside Malaysian and Singapore Community Association (MSA).

When I first visited in December 2003, the Malay Club was one of only two buildings in the section of Jermyn Street, between Princes Road and Granby Street, that had not been abandoned. By 2008, No. 7 Jermyn Street had ceased to function as a club, and was boarded up following a series of break-ins. The building had deteriorated to a state that fitted in with the more general dereliction affecting Jermyn and its surrounding streets. On the last occasion I visited, in August 2016, even the MSA signboard had been removed. The last piece of visible evidence of the one-time place of Malay Liverpool was erased forever.

This essay contains extracts from the book From World City to the World in One City: Liverpool Through Malay Lives (2016) by Tim Bunnell. Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd, it retails at major bookshops, and is also available for reference and loan at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and selected public libraries (Call nos.: RSING 305.89928042753 BUN and SING 305.89928042753 BUN).

Tim Bunnell is Professor in the Department of Geography at the National University of Singapore. His research focuses on urban development in Southeast Asia and the region’s connections with other parts of the world. Bunnell’s book, From World City to the World in One City: Liverpool Through Malay Lives, was published in 2016.

Tim Bunnell is Professor in the Department of Geography at the National University of Singapore. His research focuses on urban development in Southeast Asia and the region’s connections with other parts of the world. Bunnell’s book, From World City to the World in One City: Liverpool Through Malay Lives, was published in 2016.

NOTES

-

Sykes, O., et al. (2013). A city profile of Liverpool. Cities, 35, 299–318. Retrieved from ResearchGate. ↩

-

National Museums Liverpool. (2018). The port of Liverpool. Information Sheet 34, Maritime Archives & Library. Retrieved from National Museums Liverpool website. ↩

-

Bunnell, T. (2007). Post-maritime transnationalization: Malay seafarers in Liverpool. Global Networks, 7 (4), 412–429. Retrieved from ScholarBank@NUS. ↩

-

The area around what was once Upper Huskisson Street is today Liverpool Women’s Hospital. The electoral register for 1950 includes Ben Youp and his wife, Priscilla, living at 144 Upper Huskisson Street, as well as three other Malay men. ↩

-

Murden, J. (2006). City of change and challenge: Liverpool since 1945 (pp. 393–485). In J. Belchem (Ed.), Liverpool 800: Culture, character and history (p. 402). Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Interview with Mohamed Nor Hamid, Liverpool, 10 September 2004. ↩

-

This rosy scenario contrasts sharply with the experiences of seamen in the pre-war period. Given inferior rates of pay for seamen signing on overseas, foreign seamen settled in Britain “in the hope of obtaining better pay and conditions”. [See May, R., & Cohen, R. (1974). The interaction between race and colonialism: A case study of the Liverpool race riots of 1919. Race and Class, 16 (2), 111–26, p. 118.] However, a racially hierarchical labour market, both at sea and on land, left “coloured” people extremely vulnerable during economic downturns. ↩

-

Interview with Mohamed Nor Hamid, Liverpool, 6 October 2004. ↩

-

From its inception, the club articulated social connections with other Atlantic maritime centres – particularly New York, which had a Malay Club of its own from 1954 – and with British colonial territories, especially in the Malay world. ↩

-

Bahazin first appears in the Registry of Shipping and Seamen as “Bahazim bin Said”, but changed his name by deed poll in 1963. BT 372/1578/1. ↩

-

Bunnell, T. (2016). From world city to the world in one city: Liverpool through Malay lives. Chichester, West Sussex, UK; Malden, MA, USA: John Wiley & Sons Ltd. (Call no.: RSING 305.89928042753 BUN) ↩

-

In terms of music, it was not only the Beatles but also the wider Merseybeat phenomenon that made Liverpool “a source of wonder to the world”. See Du Noyer, P. (2007). Liverpool: Wondrous place, from the cavern to the capital of culture (p. 84). London: Virgin Books. (Not available in NLB holdings) In football, during the 1960s, Bill Shankly managed the Liverpool Football Club to unprecedented success. ↩

-

Interview with Abdul Rahim Daud, Kuala Lumpur, 6 November 2008. ↩

-

A. Ghani Nasir. (1979, October 21). Kampung Melayu di Bandar Liverpool [The Malay village in the city of Liverpool]. Berita Harian, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩