In Search of the Seven Sisters Festival

This time-honoured festival has left no tangible trace of its observance in Singapore. Tan Chui Hua pieces together oral history interviews to reconstruct its proper place in Chinese culture.

“In those days, what was most distinctive about Chinatown was the seventh day of the seventh month… on the night of the sixth day, they would have started… what was called the seven sisters’ festival, or qi jie jie (七 姐节)… women, single young women, particularly admired the story of the love between the Weaver Girl and the Cowherd. So, on the sixth day of [the] seventh month, it would be a festival for women… they would take the crafts they had made, very exquisite, beautiful handicrafts, and display them… they would put them on very long tables, place all the crafts there, and some offerings for the seven sisters; fruit, rouge, powder, embroidered clothes – very beautiful embroidered clothes for the seven sisters – and hang them up, and the women would come on the sixth to worship the seven sisters.”1

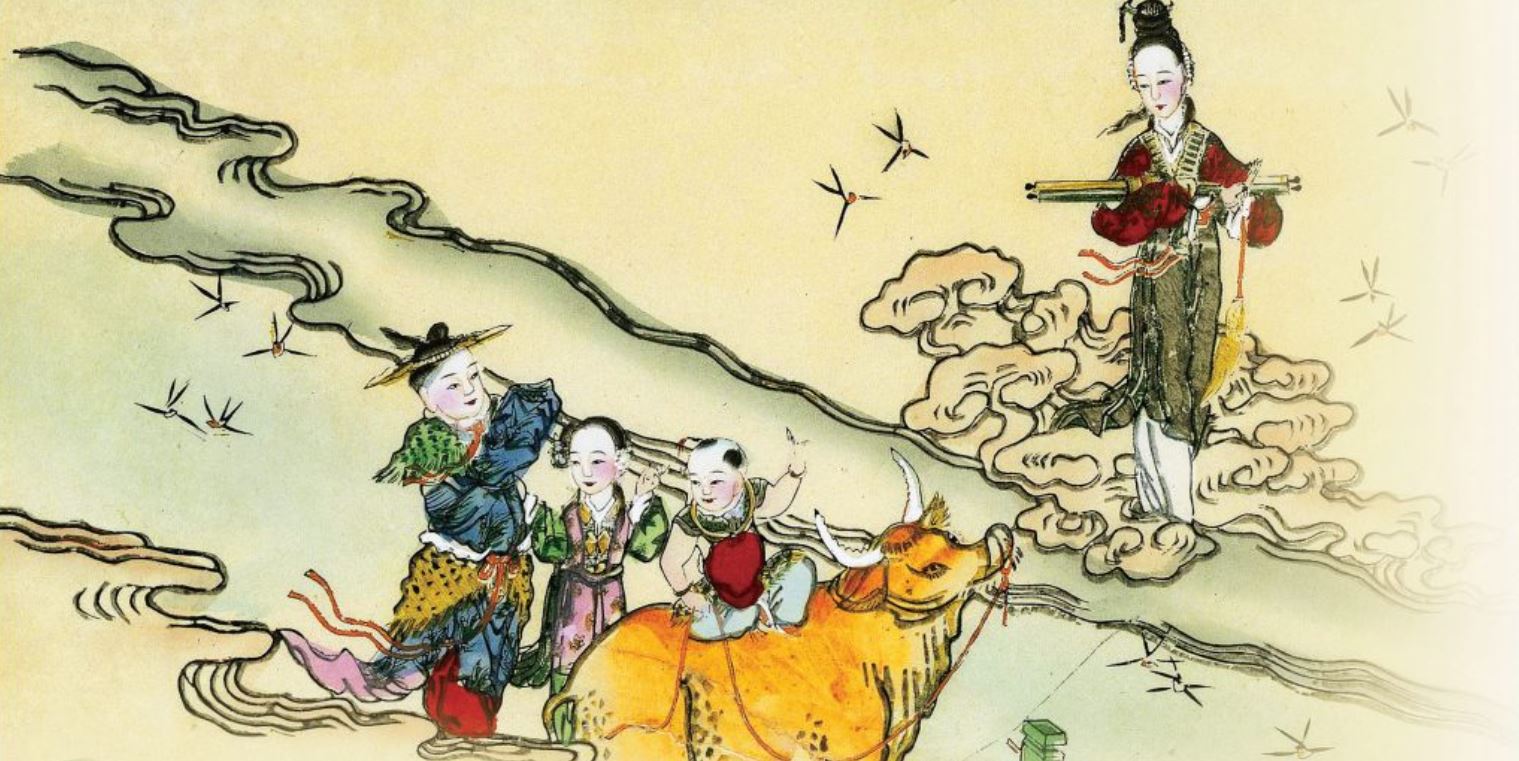

The poignant tale of The Cowherd and the Weaver Girl (牛郎织女) is well loved across East Asian cultures. Its themes of separation, reunion and unwavering devotion in the face of divine wrath inspire memorialisation in the form of religious festivals and rituals, observed on the seventh day of the seventh lunar month.2

The festivals go by various names and forms: the Chinese know it as the Seven Sisters Festival (七姐节/七姐诞), Qixi (七夕节) or Qiqiao (乞巧节), while the Japanese and Koreans call it Tanabata and Chilseok respectively.

In Singapore, the annual celebration to commemorate the legend of the Weaver Girl and Cowherd was brought here by immigrant Chinese communities, notably Cantonese female servants sworn to celibacy. Known as zishunu (自梳女) or women who “combed their hair up by themselves”, they are more commonly called amah or majie in Cantonese) (妈姐) here, as many of them took up work as domestic help in Singapore.3

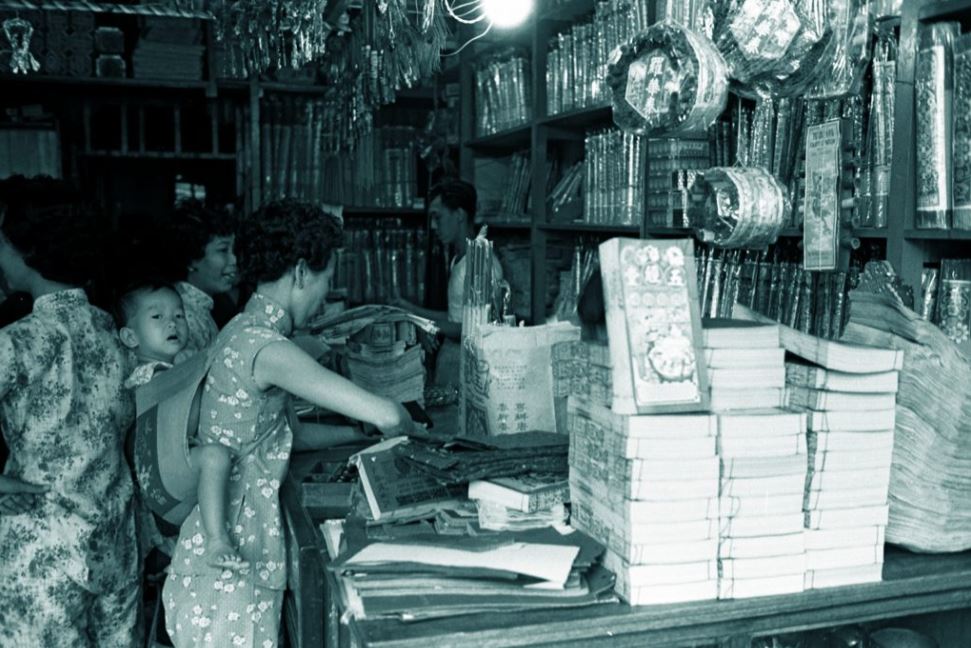

For a period in Singapore history, the observance of the Seven Sisters Festival was a much anticipated annual highlight in Chinatown, where the Cantonese community used to be concentrated.4 All across Chinatown, worship altars and displays of crafts and artworks would be set up on the eve of the festival by clan associations and sisterhoods, attracting throngs of visitors late into the night.

By the late 1970s, however, the scale of this observance had greatly diminished. Today, the Seven Sisters Festival exists only in the fading memories of former Chinatown residents.

The Task of Reconstruction

When it comes to intangible cultural heritage, documentation and preservation remain perennial challenges. In many ways, the Seven Sisters Festival is a classic illustration.

The festival has left virtually no material trace – the temples where the festivities were once held are no longer around; no archival records such as membership records or official reports are known to exist; its associated paraphernalia such as crafts, embroidery and offerings are ephemeral and not known to have been preserved; and its photographic documentation in public archives is scant. With the decline of its main group of observers, the Seven Sisters Festival has faded into memory and become a footnote in history.

To reconstruct the festival, there are two main bodies of resources: articles and columns in archived newspapers that describe the origins of the festival and its associated festivities – some of which capture the personal experiences of the writers – and a small collection of oral history interviews gathered by the National Archives of Singapore’s Oral History Centre.

However, to get a fuller sense of the festival, such as the multiplicity of experiences and actors in the festival, or to understand the significance of the festival to its actors, and to evoke the texture of memories, one needs to rely on oral history interviews.

Conducted from the 1980s onwards with former residents of Chinatown, these interviews document people’s memories of their neighbourhood, several of which include descriptions of the Seven Sisters Festival. Through these recollections, we may begin to reconstruct and re-imagine the festival at its zenith in Singapore.

Multiple variants of the tale exist, but the characters and story are largely consistent. The fairy Weaver Girl and her six sisters were known for their artistry in needle and handicrafts. When Weaver Girl fell in love with the mortal Cowherd, their union incurred the wrath of heaven. As punishment, the two were banished to either side of the Milky Way and could only meet once a year – on the 7th day of the 7th month. While the festival commemorates the unwavering devotion of the couple, the focus of its religious worship is centred primarily on the seven fairy sisters.

REFERENCE

Stockard, J.E. (1989). Daughters of the Canton delta: Marriage patterns and economic strategies in South China, 1860–1930. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. (Not available in NLB holdings)

Who, When and Where

Using the interviews as the basis for exploratory research, it is possible to piece together a fairly detailed profile of the festival. Firstly, it is clear that the festival involved many groups of people – formal organisers, informal organisers and their patrons, lay worshippers as well as casual visitors.

The driving force behind the festival was the amah community of Chinatown, where several such clan organisations and sisterhoods were established. These amahs would have planned for the event months ahead, and their clan premises served as the primary festival sites in Chinatown.

Besides these formal organisers, there were also clusters of informal organisations referred to as Seven Sisters associations (七姐会) or Milky Way associations (银河会). Such organisations were usually transient, and set up by young unmarried girls and women specifically for the purpose of the festival. The members would often comprise relatives, friends and neighbours, and tithes would be collected to cover the costs of the offerings and festivities. As many of such associations were made up of teenage girls, their patrons – usually their parents – were key figures who provided the necessary funds. The lay worshippers were generally women, both married and unmarried. These women were usually not involved in the planning and preparation for the festival, but would come together to pray and make offerings. Apart from these women, the sites would also see large crowds of visitors, who showed up just to soak in the atmosphere and enjoy the festivities.

From the oral history interviews, we know that the main group of celebrants was Cantonese. While many of the interviewees emphasised that the festival was celebrated only by the Cantonese, two interviewees took pains to mention that the Hokkien and Teochew communities observed the festival too, albeit on a much smaller scale.5

Ostensibly, the festival was held on the 7th day of the 7th month. All the oral history accounts, however, agree that festivities began on the eve. Foong Lai Kam, whose father was a Taoist priest and ran a business at Sago Lane, recalled that he would become exceptionally busy when the clock struck 11pm on the 6th day, as all the festival sites required a priest to conduct the necessary rites and rituals at the same auspicious time.6

Chay Sheng Ern Abigail, another interviewee, said that the reason was because according to the Chinese time system, 11pm is the start of the rat hour, the first hour of the day, which marks what is effectively the start of the 7th night proper.7

The recollections of the interviewees also give an idea of the scale of the festivities. Lee Oi Wah recalls the many associations organising these festivities:

“In Chinatown, there were numerous such associations. Where I lived [Kreta Ayer Street], there were at least two; one at the entrance of the street above the coffee shop, and another at the other end at another clan association. At the next street, Keong Saik Street, there were a couple. At Bukit Pasoh, there were more, three or four. The whole Chinatown had more than ten, and we would go to one after another… .”8

Another interviewee, Chia Yee Kwan describes the membership composition of these associations:

“This was very popular in Chinatown in the past. At Upper Chin Chew Street, and the street next to Upper Chin Chew Street, at Upper Hokkien Street, there were many stalls that could be organised by 10 or 20 over people. Those larger-scale ones like the Saa Kai Clan Association [an association for amahs from Shunde],… larger clan association[s] would have more than a hundred. Tens of people or perhaps more than a hundred people. Those that were of a smaller scale would have 30 or more people….”9

Unravelling Beliefs and Practices

Unlike codified religions with bodies of canonical scriptures and defined tenets, Chinese folk religion rarely displays unified beliefs. Rather, rituals and practices serve as unifying activities for believers.10 This poses another challenge to the documentation of Chinese religious festivals; without canonical texts, religious beliefs and practices reported by informants often concur only to a certain degree, and occasionally contradict one another.

This diversity in interpreting folk beliefs can be seen in the oral history interviews. To a large extent, lay worshippers and visitors to the festival sites, usually Chinatown residents, concur that unmarried female worshippers of the Seven Sisters were women who sought divine blessings in their search for a spouse as devoted as the mortal Cowherd, and – at the same time – expressed a desire to be as beautiful as the seven fairy sisters.

Some interviewees reported that unmarried women would visit the festival sites and doll themselves up in the hope of meeting their future husbands, while other interviewees disagreed – likely because they thought such behaviour was unbecoming of decent women and inappropriate for the festival.

However, granted that the main organisers were amahs who were sworn to a life of celibacy, these worshippers were clearly not in search of suitable spouses at the festival. To this end, oral history accounts with the amahs focused on descriptions of traditional practices relating to the festival rather than their personal beliefs and motivations.

Judging from the actual practices – amahs and other young unmarried women members of Seven Sisters associations would spend a good part of the year creating beautiful handicrafts – it appears that the Seven Sisters were worshipped for their artistry and mastery of needle crafts. This certainly is corroborated by research on the Seven Sisters cult in Guangdong, China, where the adherents in Singapore originated from.11

When it comes to rituals and practices relating to the Seven Sisters Festival, there is a higher degree of concurrence among those interviewed. For example, all the women mentioned that offerings would typically include a giant paper basin, cosmetics, clothing made of paper for the Seven Sisters and the Cowherd, combs, mirrors, handkerchiefs, and fruit and flowers. The priest would turn up at exactly 11pm to conduct the elaborate rituals, and the offerings would be burnt as supplication. Cantonese tongshui (糖水), or desserts, and longan tea would also be served to worshippers and visitors.

The level of descriptive detail in the interviews on ritual offerings and practices allow us to better reconstruct the festival. The following excerpt from an interview given by Abigail Chay illustrates this:

“So during this chaat cheh [Cantonese for Seven Sisters]… night, they actually would make flowers into lanterns… like a conical shape… and then they hang it in the air, and then they would make… a paper thing like a basin, and they would just burn it. And mainly they burn beautiful clothes… made of paper… and they actually put on powder, those white powder with like ‘Twin Girls’, ‘Twin Ladies’ [actually Two Girls brand], that kind of thing, and then the cologne shui [Cantonese for water], their so-called perfume at that time, at the altar… then they would just offer it for blessing… The chaat cheh day is on the seventh day of the seventh month of the Chinese calendar.”

She also recalls an interesting practice of placing items such as a bowl of water outside the window and applying make-up for blessings:

“On the chor lok, the sixth day of the seventh month, any majie [Cantonese for amah] or any lady who wanted to look very beautiful, they would put their makeup… they would also put water right outside their window where they face the sky… 11 o’clock start the new timing of the… rat timing, 11pm to 1am, they would place there… then they would leave it until the next morning, the bowl of water. If they were kiasu [Hokkien for ‘afraid to lose’], they would put one basin of water outside… they would open the cologne, the old-fashioned cologne, then the white powder for their face and whatever during that time they used for makeup… so they would put all these things overnight and hopefully it doesn’t rain. If it doesn’t rain, good weather… it seems that whatever powder you put overnight, the cologne will attract men, you will look more charming, more beautiful, and that basin of water or the bowl of water you put there, even the whole year round, will not have larva… drink already it seems… can be beautiful and can cure sicknesses.”12

A Celebration of Artistry

One of the main attractions for the throngs of visitors, sometimes as many as two or three hundred in a single venue, were the exhibits of exquisite craftworks and needlework held in conjunction with Seven Sisters festivities.

The displays were usually held on the premises of organising clan associations and Seven Sisters associations. Long tables would be set up to showcase the wide variety of arts and crafts; bigger-scale displays would occupy both levels of a clan’s shophouse building, while smaller ones would just take up a corridor’s space.

Visitors would typically go from one venue to another to admire and compare the crafts and skills of the makers. These displays would stay open, free-of-charge, until the next morning, and it was not unusual to see visitors streaming in as late as 3am.13

Here, the oral history interviews abound in descriptions of visits to these exhibitions, which in themselves are testament to the significance of the experiences to these women. One interviewee, Cheong Swee Kee, said she found the festival exceptionally exciting as such night events rarely took place in Chinatown at the time.14

Given the disappearance of the festival today and the absence of photographic documentation and preserved artefacts, the type of crafts and needlework presented at the Seven Sisters Festival can only be imagined via the detailed descriptions recounted by former Chinatown residents.

Chia Yee Kwan describes how “… cuttlefish bones [were used] to make figurines, that were very life-like. Those figurines were based on people from the ancient times, such as The Story of the Western Wing [The Romance of the Western Chambers] and the Three Kingdoms characters….”15

A wide variety of materials were used, as former resident Lee Oi Wah explains:

“Some were figurines, or miniature tables and chairs, sewn by hand; some were made with beads, tiny beads; some were made with sequins; some were made of dough… some used matchboxes to create a beautiful display.”16

Foong Lai Kam remembers:

“Most of the exhibits were made of fruit. They would stack fruit to create sculptures, such as using watermelon skin to carve out diamond or heart shapes, and stick them to create sculptures. They would display these for three days….”17

For former resident Fong Chiok Kai, what was memorable were works that used sesame and rice grains to depict mountains and rivers.18

Most of these crafts were made by amahs and served as a showcase for them to show off their skills. According to oral history interviews, the amahs would work on the crafts throughout the year during their leisure time and after hours. Lee Oi Wah recalls:

“In their leisure time, they would think about the crafts they could make, and these were their own creations, which is why the crafts had their creators’ distinctive style. So when we talk about the clothing for the seven sisters and the cowherd, we would know, ‘Oh, only this person is able to create such a beautiful set of clothing’.”

She further elaborates:

“On that night, there would be so many majie… they would take leave from their employers. They must attend this festival. To them, this festival was more important than the Chinese New Year, and they would be delighted when visitors praised the crafts, ‘Oh this is so beautiful’, or ‘Who had embroidered this piece of clothing? It is so well-done.’ They would feel that their hard work had been worthwhile, and delighted that there were so many visitors appreciating their craft.”19

The Eclipse of a Tradition

For a festival that used to be one of Chinatown’s most colourful and significant events, its eclipse was surprisingly rapid. By the 1970s, the festivities had been scaled down considerably. The few women who were asked about the festival’s decline proffered reasons such as education and changing attitudes in society, resulting in fewer believers in the community.

Other reasons cited included lack of time to commit to the organising associations and the fact that the main organisers, the amahs, were advancing in age and fewer women were moving from China to Singapore to take their place.

The oral history interviews in the collections of the National Archives are a critical resource in reconstructing this ephemeral phenomenon. In the case of the Seven Sisters Festival, the existence of a critical mass of interviews allows us to piece together detailed descriptions of the festival from the women who played different roles – as organiser, lay worshipper or visitor – and paint a textured, colourful account of times past.

More critically, it enables the comparison of multiple accounts to arrive at a more accurate, corroborated reconstruction of an intangible, cultural episode that is now relegated to the annals of history.

Tan Chui Hua is a researcher and a writer who has worked on various projects documenting the heritage of Singapore, including a number of heritage trails and publications.

Tan Chui Hua is a researcher and a writer who has worked on various projects documenting the heritage of Singapore, including a number of heritage trails and publications.

NOTES

-

Lee Oi Wah (b.1950) is a former resident of Kreta Ayer Street in Chinatown. She remembers seeing how the Seven Sisters Festival was celebrated when she was a child (Note: Interview was in Mandarin). See Yeo, L.F. (Interviewer). (1999, October 16). Oral history interview with Lee Oi Wah [MP3 recording no. 002217/9/7]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

The traditional Chinese calendar is a lunisolar calendar comprising either a 12-month, or in the case of a leap year, a 13-month cycle. Each month has either 29 or 30 days. The calendar is determined based on both the phases of the moon and the position of the sun in the sky. It is used mainly to establish the dates of major festivals such as Lunar New Year and Mid-Autumn Festival as well as to find auspicious dates for occasions such as weddings, moving house and opening a business. ↩

-

Loo, J. (2017, October–December). A lifetime of labour: Cantonese amahs in Singapore. Biblioasia, 13 (3), 2–9. Retrieved from BiblioAsia website. ↩

-

Pang, C.L. (Ed.). (2016). 50 years of the Chinese community in Singapore (p. 46). Singapore; New Jersey: World Scientific. (Call no.: RSING 959.57004951009045 FIF-[HIS]) ↩

-

Interviewee Teo Sok Koon briefly mentioned that Teochews marked the festival as well, and Goh Beng, another interviewee, discussed how Hokkiens observed the festival. See Tan, B.L. (Interviewer). (1992, December 7). Oral history interview with Teo Sok Koon [MP3 recording no. 001384/14/8] [Note: Interview was in Teochew] and Lim, I.A.L. (Interviewer). (1990, September 19). Oral history interview with Goh Beng [MP3 recording no. 001192/2/1]. [Note: Interview was in Hokkien]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Yeo, L. F. (Interviewer). (1999, November 1). Oral history interview with Foong Lai Kum [MP3 recording no. 002226/12/2]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Chua, C.H.J. (Interviewer). (2013, January 25). Oral history interview with Chay Sheng Ern Abigail [MP3 recording no. 003782/160/38]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. [Note: Interview was in English] ↩

-

Oral history interview with Lee Oi Wah, 16 Oct 1999. ↩

-

Moey, K.K. (Interviewer). (2000, November 23). Oral history interview with Chia Yee Kwan [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 002381/45/40, p. 752]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. [Note: Interview was in Cantonese] ↩

-

Grim, B.J., et al. (2016). Yearbook of international religious demography 2016 (p. 29). The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill. Retrieved from GoogleBooks website. ↩

-

Stockard, J.E. (1989). Daughters of the Canton delta: Marriage patterns and economic strategies in South China, 1860–1930 (pp. 41–47). Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Oral history interview with Chay Sheng Ern Abigail, 25 Jan 2013. ↩

-

Oral history interview with Lee Oi Wah, 16 Oct 1999. ↩

-

Yeo, L.F. (Interviewer). (2000, June 3). Oral history interview with Cheong Swee Kee [MP3 recording no. 002315/9/8]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website [Note: Interview was in English] ↩

-

Oral history interview with Chia Yee Kwan, 23 Nov 2000, p. 751. ↩

-

Oral history interview with Lee Oi Wah, 16 Oct 1999. ↩

-

Yeo, L.F. (Interviewer). (1999, November 1). Oral history interview with Foong Lai Kum [MP3 recording no. 002226/12/3]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. [Note: Interview was in Mandarin] ↩

-

Tan, B.L., & Pitt, K.W. (1982, October 12). Oral history interview with Fong Chiok Kai [Transcript of MP3 recording no. 000185/32/17, p. 222]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. [Note: Interview was in Cantonese] ↩

-

Oral history interview with Lee Oi Wah, 16 Oct 1999. ↩