“The German Medicine Deity”: Singapore’s Early Pharmacies

Timothy Pwee charts the history of Singapore’s first Western-style pharmacies through old receipts and documents from the National Library’s Koh Seow Chuan Collection.

Among the items donated to the National Library by the philanthropist and architect Koh Seow Chuan are documents dating between the 1920s and 40s from the Medical Office in Singapore. The Chinese name of this old-style Western dispensary, 德国神辳大藥房 (De guo shen nong da yao fang; or in simplified Chinese 德国神农大药房), literally translates as “German Medicine Deity Medical Office” – a name that sounds altogether incongruous as 德国 is the Chinese name for Germany, while 神辳 refers to the Chinese deity of medicine.

Dr Trebing and the Medical Hall

The history of Medical Office is predated by that of the better known Medical Hall, another German-owned dispensary housed in the landmark red-brick building near Fullerton Square on Battery Road. From the 1860s onwards, dispensaries stocked with Western medications – the Singapore Dispensary at Commercial Square and the New Dispensary at the corner of Kling and Waterloo streets – were joined by an increasing number of competitors as Singapore’s population and the accompanying demand for medical expertise, including the services of surgeons and accoucheurs (male obstetricians or midwives), grew.

In the mid-1870s, a German medical doctor by the name of Christopher Trebing arrived in Singapore and started his practice. From as early as August 1874, print advertisements for one Dr Ch. Trebing, M.D., formerly a doctor with the 82nd Regiment in Province Hessen Nassau, Germany, began appearing in local newspapers.1

By all accounts, the good doctor was successful because by the end of the 1870s, his practice had expanded from a single room in the Europe Hotel to a standalone building on Battery Road called the Medical Hall.2 Although Trebing died a decade later, the Medical Hall survived him and passed through a succession of German owners. In around 1970, the iconic Medical Hall building was demolished to make way for the Straits Trading Building.

The Medical Office’s Inauspicious Start

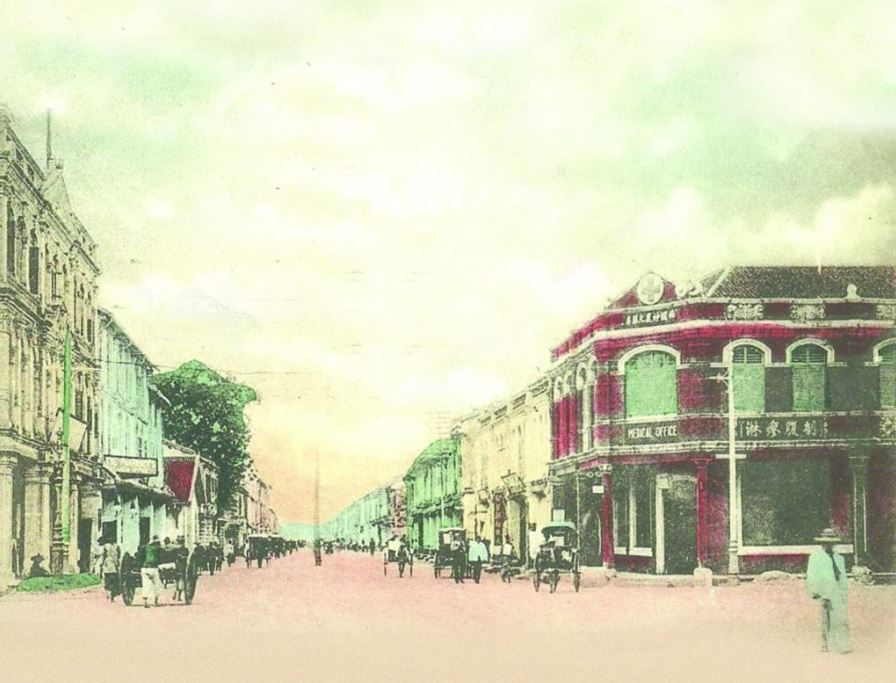

Among the competitors that emerged in the following decades was the Medical Office, set up by German chemist Emil Kahlert in 1892 at the corner of North Bridge and Bras Basah roads. German eye specialist Dr Eugene von Krudy, who was already practising in Singapore, became the dispensary’s physician.

In 1897, another German chemist by the name of Frederick Dreiss travelled to Singapore to acquire the Medical Office. Apparently, Kahlert, who had been planning to return to Germany, had taken out advertisements announcing his intention to sell the Medical Office in a number of German newspapers.

When Dreiss arrived here in April 1897, he agreed to the purchase price of $9,000 that von Krudy was asking for the Medical Office. However as Dreiss only had $7,000 on him, von Krudy agreed to lend him $2,300 and got the buyer to sign a legal document at his lawyer’s office.

Dreiss, who did not understand English, could not communicate with the lawyer and later claimed that he thought the document was merely a receipt for the loan. He later found out that the document was in fact a mortgage for the business, its stock-in-trade (i.e. the Medical Office’s stock of supplies such as drugs and equipment) and some furniture.

In October that same year, von Krudy had all the furniture, equipment and supplies seized from the Medical Office when he was not paid the sum he was owed by Dreiss. At the court hearing in November, Dreiss claimed that both Kahlert and von Krudy had conspired to cheat him by misrepresenting the Medical Office’s volume of business and duping him into signing the mortgage. During the hearings, several interesting facts emerged. One was that Kahlert had been made bankrupt back in 1891. Kahlert, however, failed to report to the Official Assignee and continued to do business in Singapore. Only when Dreiss’ lawsuit made the news did the Official Assignee summon Kahlert and ask for his finances to be examined. On hearing this, Von Krudy immediately paid off Kahlert’s debts.

Another revelation was that Max Wispauer, who became the owner of the better known Medical Hall in the 1890s, had met Dreiss when the latter first arrived in Singapore. Dreiss had sought Wispauer’s advice about buying the Medical Office and even asked to borrow $2,000 from him. However, Dreiss’ claims of being cheated by von Krudy were contradicted by various witnesses, and the presiding judge did not find sufficient evidence for the case to go to trial even though he found the entire matter altogether suspicious. Dreiss could have pursued his claim as a civil case but there are no records to indicate that he did so.3

After this debacle, von Krudy and Kahlert appeared to have left Singapore for good. In the 1899 Singapore and Straits Directory, the Medical Office was listed as a branch of the Medical Hall with Wispauer indicated as the proprietor of both dispensaries.

Regulating Drugs and Pharmaceutical Professionals

From the beginning of the 20th century onwards, quite a number of dispensaries as well as other companies doing business in Singapore began listing the names of their non-European staff in the Singapore and Straits Directory. The Medical Hall and Medical Office did not follow suit until more than a decade later when the names of three medical dispensers for the Medical Hall and two for the Medical Office respectively were mentioned in the 1912 edition of the directory.

Interestingly, the lead dispensers at both outlets – Foo Khee How who worked at the Medical Hall on Battery Road and Au Shin Wong of the Medical Office at the corner of North Bridge and Bras Basah roads – had the term “local qualification” mentioned after their names to distinguish them from their foreign colleagues. This qualification referred to was the passing of an examination administered by the new Straits and Federated Malay States Government Medical School for people applying for licences to retail poisons.4

In Britain, the licensing of people who sold drugs and medicines had begun over one-and-a-half centuries ago. Shopkeepers who sold drugs, both herbal remedies as well as chemically derived ones, had started to organise themselves with the formation of the Pharmaceutical Society in 1841. This was around the same time that statistics on drug usage patterns and deaths due to the misuse of drugs were being collected. The 1852 Pharmacy Act in Britain resulted in the establishment of a register of pharmacists and limited the use of the job title to only those registered with the Pharmaceutical Society. This, in turn, led to the Pharmacy Act of 1868, which restricted the sale of specific drugs and poisons to qualified and registered pharmacists.5

It took another few decades before Singapore followed suit. Narcotic substances such as opium and morphine were of particular concern as they were highly addictive, and the first ordinances restricting their availability and use were passed in 1894 and 1896 respectively. In 1905, the Poisons Ordinance came into force, limiting the sale of listed dangerous chemicals to licensed persons. In 1910, the Poisons Ordinance was joined by the Deleterious Drugs Ordinance, which further limited the distribution of certain drugs (and syringes) to registered pharmacists, doctors and dentists. This meant that dispensaries had to have a registered person on its staff who was authorised to import or buy medical supplies, prescribe and fill prescriptions, and keep a record of transactions.

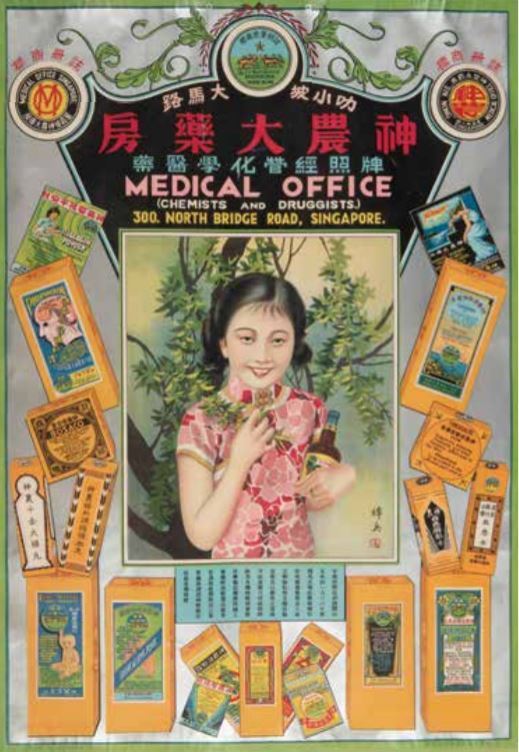

Interestingly, Western dispensaries back then in Singapore provided the kind of services that Chinese medical halls do today. At the beginning of the 20th century, the mass manufacturing of pharmaceuticals as an industry had only just begun and Western medical dispensaries prepared their own array of treatments, including most ointments, lotions, mixtures and even tablets, in the shop itself.6 As late as the 1960s, the pharmaceutical practical examination at the University of Singapore required students to make tablets on the spot. Going by an account of a student from that era, if the examiner managed to break the pill with his hands, the student would immediately fail.7

The End of a (German) Era

World War I, which began in 1914, saw increasing hostility by the British Empire towards Germans, both by nationality and by birth. In August 1915, Sir Evelyn Ellis, a member of the Legislative Council of the Straits Settlements, raised the motion that the Alien Enemies (Winding Up) Ordinance of 1914 be applied to both the Singapore Oil Mills and the Medical Hall (it had already been applied to other firms). He said that the current owner of the Medical Hall – despite being a naturalised British subject – was “an imitation Britisher” and “a German at heart”, and that “the business was being carried on purely in German interests”.8 Although Ellis later asked to withdraw the motion, the execution of his orders was merely delayed.

On 19 February 1916, The Malaya Tribune reported that the Colonial Secretariat in London had ordered all enemy firms in the colonies to be liquidated with immediate effect.9 In line with this order, the liquidation notice for The Medical Hall Limited was published three days later on 22 February.10 Finally, two years later, on 15 April 1918, both the Medical Hall and the Medical Office were auctioned off by the Custodian of Enemy Property, thereby closing the chapter on the era of German pharmacies in Singapore.11

Decades later, the memory of Germans running the Medical Office still loomed large in popular memory. In T.F. Hwang’s “Down Memory Lane” column published on 24 March 1979 in The Straits Times, he noted that “to taxi operators and SBS bus workers, the name [of Bras Brasah Road] in Hokkien/Teochew dialects is Teck Kok Sin Long [德国神农]”,12 Teck Kok meaning Germany and Sin Long being the Chinese deity of medicine.

As a result of the forced seizure and auction, the Medical Hall at Battery Road was taken over by pharmacist George W. Crawford in partnership with Dr A.P. Lena van Rijn.13 The Medical Office, on the other hand, was acquired by a group of former staff led by its lead dispenser Foo Khee How, who later became the firm’s manager.14

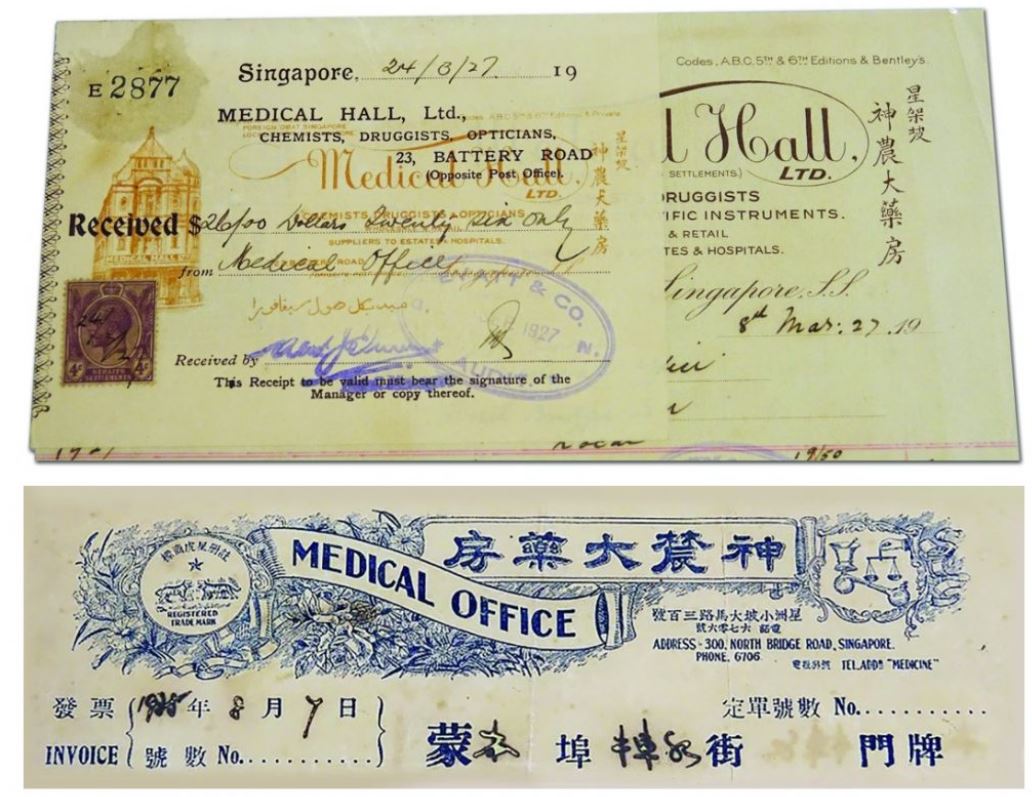

The business receipts and invoices in the Koh Seow Chuan Collection, the earliest of which date from the 1920s, reveal that both the Medical Office and the Medical Hall used the same Chinese name 神農大藥房 (the Medical Office used the Chinese characters 神農大藥房 in the advertisements it ran in the Chinese press but 神辳大藥房 on its letterhead – 農 and 辳 were apparently used as variants of each other). This could suggest that the Chinese name for the Medical Hall originated sometime before World War I and continued to be used by both firms even though they were separate entities.

The Medical Hall’s Foo Khee How passed away in December 1931, leaving behind four sons and five daughters.15 Foo Chee Guan, one of Foo’s sons, studied medicine at the Hong Kong College of Medicine where Sun Yat-sen, the founding father of the Republic of China, had graduated back in 1892. When Foo Chee Guan graduated, he returned to practise at the Medical Office just before the outbreak of World War II in 1942.16

From the oral history recordings of Foo Tiang Fatt, nephew of Foo Chee Guan, we know that some members of the Foo family escaped to their rubber plantation in the Karimun islands west of Singapore for the duration of the Japanese Occupation. Foo Chee Guan and his cousin Foo Chee Foong, however, stayed behind and continued to operate the Medical Office.

From perusing the business receipts of the Medical Office in the Koh Seow Chuan Collection and a number of newspaper articles, it appears that the Foos contributed to various causes before the Japanese Occupation, including the China Relief Fund, which helped raise money for China’s war effort against Japan, and St Andrew’s Cathedral. According to the bills of exchange in the collection, pre-war imports came mainly from Europe and America. The collection also contains numerous receipts for local purchases made at other dispensaries. The receipts issued in 1943 during the Japanese Occupation show that medicines were still available for sale at the Medical Office, particularly Japanese-made ones.

Modernity and Manufacturing

When the war ended in 1945, business activity in the Medical Office picked up. Foo Chee Guan and Foo Chee Foong took charge of the company in 1955, and the former’s nephew, Foo Tiang Fatt, joined them the following year.17 The 1960s, however, marked the beginning of the sunset years for the Medical Office as well as the other old-style Western pharmacies that prepared their medicines manually on their premises. The advent of the Western drug manufacturing industry and modern pharmacy retail chains were slowly beginning to make their presence felt.

In the 1970s, Cold Storage started expanding its Guardian Pharmacy outlet into a chain and began opening branches all over Singapore. In 1988, Hongkong-based Watsons Personal Care Stores entered the Singapore market and set up outlets in shopping malls and housing estates.18 When the government acquired the premises of the Medical Office in 1982, control of the company was passed to Foo Tiang Fatt and his cousin Foo Tiang Suan, and the firm moved to Geylang Road.19

Foo Chee Guan retired from practising medicine in 1985, at 74 years of age.20 In the end, faced with increasing costs, the difficulty of finding reliable staff and poor business, the Medical Office was shuttered down for good and deregistered in 2012.

Timothy Pwee is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. He is interested in Singapore’s business and natural histories, and is currently developing the library’s donor collections around these areas.

Timothy Pwee is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. He is interested in Singapore’s business and natural histories, and is currently developing the library’s donor collections around these areas.

NOTES

-

Page 3 advertisements column 3: Miscellaneous: Ch. Trebing, M. D. (1874, August 29). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Keaughran, T.J. (1879). The Singapore directory for the Straits Settlements (p. 105). Singapore: Straits Times Office. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Dispute about a “Medical Office”. (1897, November 3). The Straits Times, p. 3; The “Medical Office” prosecution. (1897, December 21). The Singapore Free Press, p. 392. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Freer, G. D. (1907, August 30). Appendix 7: Straits and Federated Malay Straits Government Medical School (p. 73). In The Straits Settlements Medical Report for the Year 1906 (pp. 73–75). (Microfilm no.: NL1062); List of persons licensed under “The Poisons Ordinance 1905”. (1908, February 21). Straits Settlements Government Gazette (p. 308). (Microfilm no.: NL1064). ↩

-

Derks, H. (2012). History of the opium problem: The assault on the East, ca. 1600–1950 (pp. 113–120). Leiden; Brill, Boston. (Call no.: RSEA 363.450950903 DER) ↩

-

Lee, P. (Interviewer). (1988, May 22). Oral history interview with Dr Wong Heck Sing [Transcript of cassette recording no. 002024/09/02, pp. 23–24]; Ng, B. (Interviewer). (2012, November 6). Oral history interview with George Yuille Caldwell [Cassette recording no. 003776/38/18]; Ng, B. (Interviewer). (2012, November 29). Oral history interview with George Yuille Caldwell [Cassette recording no. 003776/38/20]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Personal communication with a graduate of the 1960s. ↩

-

Legislative Council: Medical Hall. (1915, August 14). The Malaya Tribune, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Fiat Justitia. (1916, February 19). The Malaya Tribune, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Page 7 advertisements column 2: Notice. (1916, February 22). The Malaya Tribune, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

By order of the custodian of enemy property. (1918, April 3). The Singapore Free Press, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

T.F. Hwang takes you down memory lane. (1979, March 24). The Straits Times, p. 16. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Death of Mr. G.W. Crawford. (1941, September 29). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Singapore & Straits Directory (p. 193). (1917). Singapore: Printed at the Mission Press. (Microfilm nos.: NL 185–1190) ↩

-

Deaths: Foo Khee How. (1931, December 21). The Malaya Tribune, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

73 and still going strong. (1984, November 12). The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Death. (1955, May 26). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Chan, J. (Interviewer). (2013, December 30). Oral history interview with Foo Tiang Fatt [Cassette recording no. 003840/11/1]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Koh, T.Y. (1981, August 15). Another Guardian Pharmacy store soon at Goldhill. The Business Times, p. 5; Subramanium, S. (1989, June 16). Watson’s to open its 11th outlet in Funan Centre next week. The Straits Times, p. 43. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Oral history interview with Foo Tiang Fatt, 30 Dec 2013. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 12 Nov 1984, p. 11. ↩