Looking Back at 700 Years of Singapore

Singapore’s history didn’t begin in 1819 when Stamford Raffles made footfall on the island. Tan Tai Yong makes sense of our 700-year history in this wide-ranging essay.

On 28 January 1819, Stamford Raffles and his entourage landed on an island that was home to some 1,000 Chinese, Malay and orang laut (“sea people” in Malay). Soon after their arrival, they met Temenggong Abdul Rahman, the local chief in Singapore, and Tengku Long – eldest son of the late sultan of the Johor-Riau-Lingga empire – who was later installed by the British as Singapore’s first sultan, Hussein Mohamed Shah.

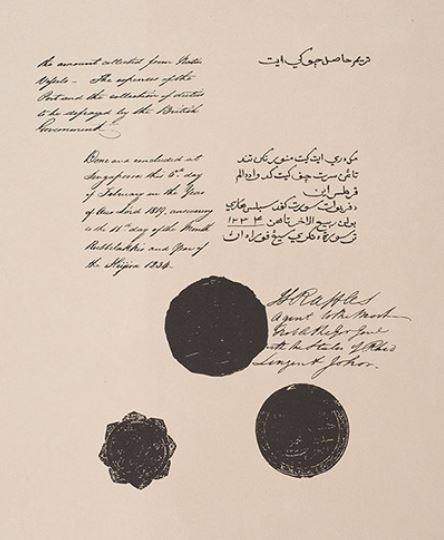

Along with a formal ceremony and banquet, a treaty was signed on 6 February 1819 allowing the British East India Company (EIC) to set up a trading post on the island.1 Conventional narrative looks back to this day as the beginning of modern Singapore.

Wa Hakim, then 15 years old, was one of the orang laut who was present on the day the British arrived. Already an old man in his 80s, he shared his recollection of what transpired on that day:

“I remembered the boat landing in the morning. There were two white men and a Sepoy on it. When they landed, they went straight to the Temenggong’s house. Tuan Raffles was there, he was a short man… Tuan Farquhar was there; he was taller than Tuan Raffles and he wore a helmet. The Sepoy carried a musket. They were entertained by the Temenggong and he gave them rambutans and all kinds of fruit… Tuan Raffles went into the centre of the house. About 4 o’clock in the afternoon, they came out and went on board again.”2

But the story of Singapore goes back much further. The island as it was 700 years ago in fact shares a number of similarities with today’s cosmopolitan city-state. In the 14th century, Singapore was already a centre for a vast trading network and actively engaged in commerce with neighbouring ports and regions. Commodities such as hornbill casques and lakawood (a type of aromatic wood used as incense) were exported from Singapore, or Temasek, as it was known then.

Archaeological finds provide evidence that early Singapore imported ceramic wares from China, along with other products from around the region. Singapore also traces a royal lineage that has its roots in the 13th century, beginning with a prince from Palembang, Sri Tri Buana (also known as Sang Nila Utama), and ending when the last king, Iskandar Shah, fled to Malacca, following a scandal involving the daughter of a royal minister and an invasion by Majapahit forces from Java.3

(Right) Earthernware shards from circa 14–15th century recovered from Empress Place indicate that Singapore had social, economic and cultural links with other population centres in maritime Southeast Asia, including Sumatra, Java and Borneo. Image reproduced from Kwa, C.G., Heng, D.T.S., & Tan, T.Y. (2009). Singapore, a 700-Year History: From Early Emporium to World City (p. 44). Singapore: National Archives of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 959.5703 KWA-[HIS])

All this is proof that Singapore was already a city of considerable stature centuries even before Raffles set foot here. Hundreds of years before modern Singapore came to be, the island was already firmly embedded in a wider regional web and frequently engaged with powers and political entities well beyond its immediate borders.

Yet, it is undeniable that Raffles and his deputy William Farquhar, along with the machinery of the colonial administration, played an instrumental role in furthering Singapore’s rise into a bustling port-city, and by extension, the global city we know today. The year 1819, therefore, marks the beginning of a journey that resulted in the eventual blossoming of a cosmopolitan and independent republic.

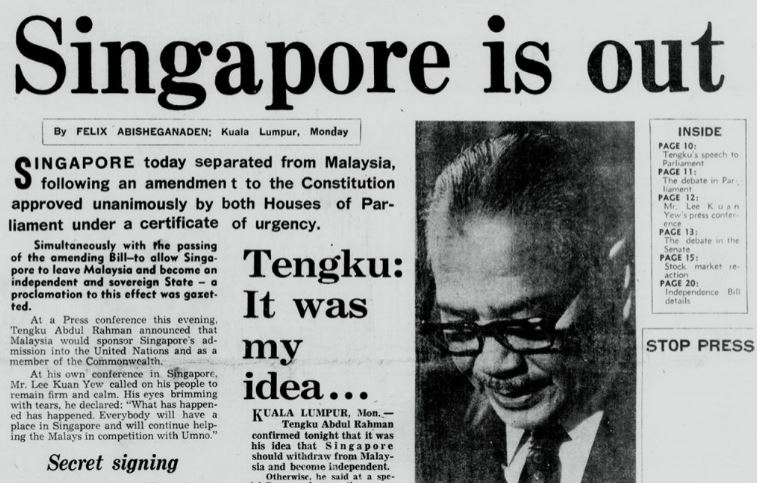

Two hundred years after that fateful day, we can reflect on our history and heritage and the elements that contributed to the Singaporean identity and spirit as we know it today. A series of setbacks that threatened to pronounce the demise of the island at various stages of its post-1819 history, such as the devastation of World War II, the exit of the British, the merger with the Federation of Malaya and then separation from Malaysia, have become inextricably woven into a narrative that speaks of ever-resolute tenacity.

Linkages and Connectivity

A confluence of regional and international factors contributed to the rise of Temasek as a port in the 14th century. Under the Song dynasty, Chinese trade with Southeast Asia grew between the 12th and 13th centuries. The new trade policies reduced reliance on a single main entrepôt – Srivijaya in Palembang – in the Malacca Strait and encouraged the rise of numerous autonomous port-polities in the region that engaged directly with China.4

At the end of the 13th century, the aforementioned Palembang prince Sri Tri Buana was on an expedition in Bentan (Bintan) when he spotted the white sandy coast of Temasek from a distance. He decided to relocate here and rename the island Singapura.5 We know something of Temasek’s life, trade, people and culture from sources such as the 14th-century Daoyi Zhilue (岛夷志略; A Description of the Barbarians of the Isles), a collection of accounts from Yuan dynasty Chinese traveller and trader Wang Dayuan (汪大渊), and Sejarah Melayu (Malay Annals), a 17th-century Jawi work that traces the history and genealogy of the Malay kings of the Malacca Sultanate.6

Interestingly, almost everything we know of Singapore from this period of its history comes from textual sources beyond its shores – all of which point to early Singapore as being part of a much wider sphere and sustained by trade.

Similarly, the establishment of modern Singapore in the early 19th century had very much to do with its position as a strategic location for trade. Lying at an important crossroad along the East-West trade route between the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean, the Malacca Strait was the key passageway through which the markets of the Indian subcontinent, and the Middle East and beyond gained access to China, Southeast Asia and Australasia.7

As the Dutch held sway over much of Southeast Asia at the time and controlled the seaways through which EIC ships had to pass, Raffles saw the need for the company to secure a port for itself along the India-China trade route.8 In 1818, Raffles described the problem in a letter to his superiors in the EIC:

“The Dutch possess the only passes through which ships must sail into the Archipelago, the straits of Sunda and Malacca; and the British have now not an inch of ground to stand upon between the Cape of Good Hope and China, nor a single friendly port at which they can water and obtain refreshment.”9

Singapore was a rich prize because of its location. Soon after the British arrived, the value of the island’s entrepôt trade rose to almost 40 percent of its total commerce.10 Colonial Singapore became inextricably linked by trade – through the free flow of goods, people and ideas – to the larger world.

As Singapore’s soil was unable to support large-scale agriculture, and sustained only a small population at the point of Raffles’ arrival, the young settlement became reliant on its hinterland for essential resources. People were also needed to enable the port to thrive. By 1821, the population in Singapore had grown to 5,000, many of whom were Malaccans who had followed William Farquhar when he moved here to become Resident of Singapore (he was previously Resident of Malacca).11 In addition, the EIC brought prisoners from India to build local infrastructure. Therefore, diverse peoples from around the region and beyond came together in a collective effort to bring life to modern Singapore.

The heavy reliance on trade, however, meant that the fortunes of Singapore were inevitably susceptible to larger economic developments beyond its shores. At the turn of the 20th century, the adverse impact on the local economy caused by volatile commodity prices, notably rubber, illustrated the danger of being heavily dependent on the world market.

Trade continued to play a major factor in Singapore’s revenue even after independence, and remains a vital part of the economy today. Upon becoming an independent nation in 1965 and losing Malaysia as a hinterland, the government turned its attention from regional trade to a more global perspective. To embed itself in the international market, Singapore began establishing stronger communication links and more seamless transportation networks.12

Today, as one of the world’s most trade-dependent nations, Singapore continues to seek new ways to stay relevant in the global market and remain connected with the rest of the world. This often explains its ambition to punch above its weight in order to entrench itself in the global community.

Resilience and Enterprise

As mentioned earlier, when Farquhar announced he was moving to Singapore to set up a new British settlement, thousands of Malaccan men left their homes to start a new life here, despite Dutch attempts to stop the mass migration. Among the motley group of traders, peddlers, carpenters, labourers and other workers were a number who quickly rose to become prominent businessmen: in the words of Raffles’ Malay scribe Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir – better known as Munshi Abdullah who published his autobiography, Hikayat Abdullah (Stories of Abdullah), in 1849 – Malacca fell into a “drought” while Singapore experienced “the rain of plenty”.13 In his book, Munshi Abdullah describes the rapid transformations that took place in the first few years of the settlement:

“I am astonished to see how markedly our world is changing. A new world is being created, the old world destroyed. The very jungle becomes a settled district while elsewhere a settlement reverts to jungle. These things show us how the world and its pleasures are but transitory experiences, like something borrowed which has to be returned whenever the owner comes to demand it.”14

The men who came with Farquhar were determined to carve out a better life for themselves, seizing the opportunity to start afresh under the British. In the decades that followed, the colony continued to witness the arrival of tens of thousands of Chinese migrants in search of better opportunities: by 1897, there were 200,000 inhabitants in Singapore. Among them was the great-grandfather of the man who was to become the first prime minister of independent Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew.15

Many of these migrants worked as coolies, trishaw riders and shop owners, and toiled away to send whatever money they could back to their families in China. Since these workers were often men, Singapore soon faced a gender imbalance, which was mitigated in the 1900s by a surge in Chinese female migrants. Among these women were hardy samsui labourers, who worked in tin mines and construction sites, and amahs (domestic servants).16 These women were just as determined as the men to eke out a living.

Singapore became a place of opportunity and new beginnings: while these migrants laboured to send most of their hard-earned wages to their families back home, they also seized the fresh start that the island offered to build a new life.

While still tied by birth to the lands they came from, the new arrivals were also invested in building new lives in Singapore, and – when they started families of their own here – to building a better life for their children. The latter decades of the 1800s to early 1990s saw a reform in education, with more government-operated English schools, as well as ethnic communities taking greater ownership in providing vernacular education.17

New Chinese, Tamil and Muslim-Malay schools were established, teaching a more updated curriculum in their respective ethnic languages. However, the better jobs still went to English-educated locals. Still, Asians of any calibre invariably faced a ceiling when it came to their career advancement: in 1912, the British Empire officially barred non-Europeans from assuming senior roles in public administration.18

As these issues of discrimination brewed, locals began to ponder over the idea of nationalism, and what it meant for Singapore, whose population comprised mainly migrants who hailed from different countries. Eunos Abdullah, the first Malay Legislative Councillor, spoke up against a colonial administrative system that favoured foreigners over locals, and argued for greater education and career opportunities for “sons of the soil”, a term he gave to the Malays. He saw Malays as collectively belonging to the nation, and rejected the idea of any allegiance to the local sultan.19

Likewise, the Straits Chinese community also faced the dilemma of remaining loyal to a distant and increasingly politically unstable China, or declaring allegiance to Singapore and a British administration in which their career opportunities were curtailed.20

The early 1900s saw people in Singapore becoming more disillusioned by their lowly status under the British. With this disgruntlement began a dialogue about what nationalism meant in a colony of diverse peoples. The dialogue was to continue for decades afterwards.

With the devastation of World War II in Singapore – and the failure of the British Empire in protecting Singapore – came further questions about nationalism and independence.21 Britain surrendered and the locals were left to face the brutality of the Japanese. Literature that hinted of the suffering of war, anti-Japanese sentiments and expressions about nationalism appeared in newspapers, such as the poems of the local Malay poet Masuri S. N.

Anti-Japanese resistance movements also took root, the chief example being the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA) created by the Malayan Communist Party.22 In the wake of the failure of the colonial government to protect Singapore, people had no choice but to hold their ground alone.

The Japanese surrendered in 1945 and the British returned. They were in for a rude shock; instead of the warm reception they were expecting, what they saw resounding in the streets of Singapore was a cry for freedom or “merdeka” among English-educated locals. Their calls for independence were met with strong support from the other communities.23

Having been left to fend for themselves and endure the atrocities of war, the people of Singapore now knew that they could not count on a foreign government for their security and prosperity. They began to have a newfound confidence, driven by the disappointment of being abandoned during the war. They now desired to be freed from the masters who had proven themselves unworthy.

Yet with the abrupt arrival of independence in 1965, a massive burden was thrust upon the new government led by the People’s Action Party. How the first generation of leaders laid the foundations of what Singapore has become today is a whole other story of its own, complete with its fair share of moral courage, enterprise and resilience against a backdrop of struggle and turbulence.

Diversity and Differences

Whether in colonial, independent or early Singapore, a diverse, migrant population has always characterised the island-city. In Daoyi Zhilue, Wang Dayuan notes that Chinese people lived alongside orang laut natives at Longyamen (“Dragon’s Tooth Strait”; most likely referring to the waterway between Sentosa and Labrador Point), where ships called for trade. Later, the Malaccan immigrants who came with Farquhar largely comprised Indians and Straits Chinese.24

In 1822, Raffles, dissatisfied with the way Farquhar had developed the settlement, instructed assistant engineer Philip Jackson to draw up a plan for the town of Singapore. Titled “Plan of the Town of Singapore” (more commonly known as Raffles Town Plan or Jackson Plan), the blueprint demarcated living spaces and organised the island’s layout according to ethnic communities. Hence, the diverse population was segregated rather than united, with different neighbourhoods laid out for the Chinese, Malays, Bugis and Indians, as well as a dedicated European Town by the Singapore River.25

Each ethnic group retained its distinct culture and livelihood, and continued speaking its native language or dialect. Because the groups were kept separate, there was minimal interaction and little need to negotiate differences in the pursuit of unity. As already mentioned, the idea of a distinct Singaporean nationhood and the question of national identity only began to take shape around the 1900s, as Asian locals became better educated and increasingly dissatisfied with their lot.

By 1833, “Chinese, Malays, Bugis, Javanese, Balinese, natives of Bengal and Madras, Parsees, Arabs, and Caffrees [Africans]” could all be found in Singapore, as a great variety of ships sailed into its protected harbour.26 The story of Singapore as a thriving port city in Asia is “the story of multi-racial communities and networks”.27

In the earlier decades of the 20th century, The Malaya Tribune received much support as the newspaper that expressed the voices of the local communities. Readers and contributors often discussed ideas of nationhood and belonging, and of their role in Singapore.

As Chinese and Indian workers continued to stream into Malaya in search of work, questions of who were the rightful sons and heirs of the Malayan land (was it open to all races who claimed Malaya as their home, or were only the Malays eligible?), and whether it was appropriate to maintain ties with one’s country of origin, were debated in the Tribune. One lawyer wrote in the newspaper: “No matter what their nationality is, they [the local-born] should be proud to be called Sons of Malaya as much as Sons of other Countries.”28

Identity and Unity

In light of the increasing dissatisfaction with the colonial administration, a sense of collectiveness among the locals began simmering: what was the significance of their living together, and how were these dwellers to distinguish themselves through their sense of belonging to this island? If these migrants of diverse backgrounds considered this land as their home, how should they be united in order to be set apart?

As much as these issues lingered in people’s minds, they only remained abstract concepts until the British left and a united Malaya – and later, a united Singapore – was born. When Malayans were left to govern themselves, free of their colonial masters, the questions of identity and unity became more pertinent than ever. These questions now needed answers, and the answers would come to impact the everyday lives of the people.

Questions of racial identities and citizenship featured prominently in the negotiations leading to Singapore’s merger with the Federation of Malaya in September 1963. While part of the Federation, tensions ran high as Singapore’s Chinese-dominant People’s Action Party (PAP) directly contested the ruling United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), which sought to protect Malay interests. As a result, riots broke out in Singapore between Chinese and Malay factions in 1964.29 Even after Singapore and Malaysia went their separate ways and Singapore gained independence in 1965, the racial divide within the island’s boundaries presented the PAP government with the daunting task of managing these racial tensions and forging a common Singaporean identity.

The ruling party’s stand was clear: equal treatment across ethnic groups, and integration rather than separation. English, a “neutral” language among the main ethnic groups, was to be the language of business as well as of inter-racial communication in Singapore. English was hence taught alongside ethnicity-based mother tongue languages, in line with the government’s bilingualism policy.30 By 1987, all schools used English as the primary medium of instruction – bringing the curtain down on ethnic-based vernacular schools – with Chinese, Malay and Tamil taught as second languages.31

A trans-cultural Singaporean identity and business practicality took precedence over one’s ethnicity, with the government envisioning that racial differences would give way to a sense of collective nationhood. Concrete policy steps were taken: in stark contrast to the racially segregated clusters that Raffles mandated, the PAP set ethnic quotas in public housing estates in 1989, ensuring that every such estate and block of flats housed families of different races.32 This move made clear the government’s stand against the formation of communal enclaves: in the PAP’s opinion, the key to harmony was not to keep diverse peoples apart, but to bring them together.

Since Singapore’s earliest days as an entrepôt 700 years ago, diversity has been a constant. Singapore has always been a city of migrants, who brought with them trade, dynamism, cultural diversity, and the wherewithal to make the nation what it has become today. Colonial Singapore required migrants to build up its infrastructure and develop its economy, and all throughout its history, waves of foreigners have been arriving on its shores in search of better prospects.

Contemporary Singapore is no different: as the city continues to search for new ways to remain relevant in the global marketplace, people from all around the world find themselves here in search of investment and work, and to carve out a better life for themselves.

Singapore continues to welcome the influx of new immmigrants, while also seeking ways to integrate these newcomers. As the city’s population continues to grow more diverse, its identity also becomes increasingly more fluid. One thing is certain: as the canvas grows more colourful, the difficult task lies in blending the colours seamlessly while ultimately creating a harmonious whole.

Professor Tan Tai Yong is the second President and Professor of Humanities (History) at Yale-NUS College. He is also Honorary Chairman of the National Museum of Singapore and a member of the Board of Trustees of ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, among other appointments.

Professor Tan Tai Yong is the second President and Professor of Humanities (History) at Yale-NUS College. He is also Honorary Chairman of the National Museum of Singapore and a member of the Board of Trustees of ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, among other appointments.

Notes

-

Frost, M.R., & Balasingamchow, Y.-M. (2009). Singapore: A biography (pp. 40–46, 48). Singapore: Editions Didier Millet and National Museum of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 FRO-[HIS]) ↩

-

Haughton, H.T. (1882, June). Landing of Raffles in Singapore by an eye-witness. Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 10, p. 286. Retrieved from Internet Archive. ↩

-

Heng, D. (2011). Situating Temasik within the larger regional context: Maritime Asia and Malay State formation in the pre-modern era (pp. 46–47). In D. Heng & Syed Muhd Khairudin Aljunied (Eds.), Singapore in global history. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57-[HIS]); Frost & Balasingamchow, 2009, pp. 24–26. ↩

-

Kwa, C.G, Heng, D., & Tan, T.Y. (2009). Singapore, a 700-year history: From early emporium to world city (p. 23). Singapore: National Archives of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 959.5703 KWA-[HIS]); Heng, 2011, p. 44. ↩

-

Kwa, Heng & Tan, 2009, p. 24; Brown, C.C. (1952). The Malay Annals. Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 25(2), 29–31. Singapore: Malayan Branch, Royal Asiatic Society. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.5 JMBRAS-[GBH] ↩

-

Ptak, J. (1995). Images of Maritime Asia in two Yuan texts: “Daoyi zhilue” and “Yiyu zhi”. Journal of Song-Yuan Studies, 25, 47–75. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Kwa, Heng & Tan, 2009, p. 64. ↩

-

Tan, T. Y. (2005). Early entrepot portal: Trade and founding of Singapore (p. 1). In A. Lau & L. Lau (Eds.), Maritime heritage of Singapore. Singapore: Suntree Media. (Call no.: RSING q387.5095957 MAR) ↩

-

Frost & Balasingamchow, 2009, p. 47. ↩

-

Frost & Balasingamchow, 2009, pp. 18, 63, 65; Tan, 2005, p. 3. ↩

-

Rajaratnam, S. (1972, February 6). Singapore: Global city; National Archives of Singapore. (2016, June 24). Connecting Singapore to the world – from submarine cables to satellite earth stations (1960s - 1970s). Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Frost & Balasingamchow, 2009, p. 63; Abdullah Abdul Kadir (1849). Hikayat Abdullah. Singapore: Mission Press. (Microfilm nos.: NL7912, NL9717, NL7810) ↩

-

Abdullah Abdul Kadir. (1985). The Hikayat Abdullah: The autobiography (A.H. Hill, Trans.) (p. 162). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.51032 ABD) (Original work published 1969). ↩

-

Frost & Balasingamchow, 2009, pp. 132, 150; Singapore: Island, city, state. (1990). (p. 83). Singapore: Times Editions. (Call no.: RSING 959.5705 SIN-[ISK]) ↩

-

Singapore: Island, city, state, 1990, pp. 84–85; Frost & Balasingamchow, 2009, pp. 152, 204–205. ↩

-

Frost & Balasingamchow, 2009, p. 182. ↩

-

Frost & Balasingamchow, 2009, pp. 182–183. ↩

-

Frost & Balasingamchow, 2009, pp. 189, 197. ↩

-

Frost & Balasingamchow, 2009, pp. 194–195. ↩

-

Frost & Balasingamchow, 2009, pp. 275, 314. ↩

-

Frost & Balasingamchow, 2009, pp. 306, 315. ↩

-

Frost & Balasingamchow, 2009, pp. 322, 323. ↩

-

Frost & Balasingamchow, 2009,pp. 23, 63. ↩

-

Frost & Balasingamchow, 2009, p. 66. ↩

-

Frost & Balasingamchow, 2009, p. 84. ↩

-

Lee, P., & Wang, N. (2017, January). Port cities: Multi-cultural emporiums of Asia. Muse SG, 9, p. 5. Singapore: National Heritage Board. Available via PublicationSG. ↩

-

Frost & Balasingamchow, 2009, pp. 200–202. ↩

-

Frost & Balasingamchow, 2009, pp. 414, 417. ↩

-

Chong, T. (2011, July). Manufacturing authenticity: The cultural production of national identities in Singapore. Modern Asian Studies, 45(4), p. 887. London: Cambridge University Press. (Call no.: R 950 MAS) ↩

-

The exception was that Special Assistance Plan schools offered both English and Chinese at the first language level. See Alfred, H., & Tan, J. (1983, December 22). It’s English for all by 1987. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Wee, A. (1989, February 17). Racial limits set for HDB estates. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩