Making History

A treaty that sealed Singapore’s fate, a contract for the sale of child brides, and a drawing of an iconic theatre are among the items showcased in a new book, 50 Records from History, published by the National Archives of Singapore.

A Treaty Most Unfriendly

Title: Record of the Treaty of Friendship and Alliance, 2 August 1824

Source: National Archives of Singapore

Year created: Copy made in 1841

Type: Document

Accession no.: SSR R7

Singapore came under the control of the British East India Company (EIC) on 2 August 1824. This was after the second Resident of Singapore, John Crawfurd, had signed a treaty with Sultan Hussein of Johor and Temenggong Abdul Rahman to officially transfer their sovereignty over the island to the British.

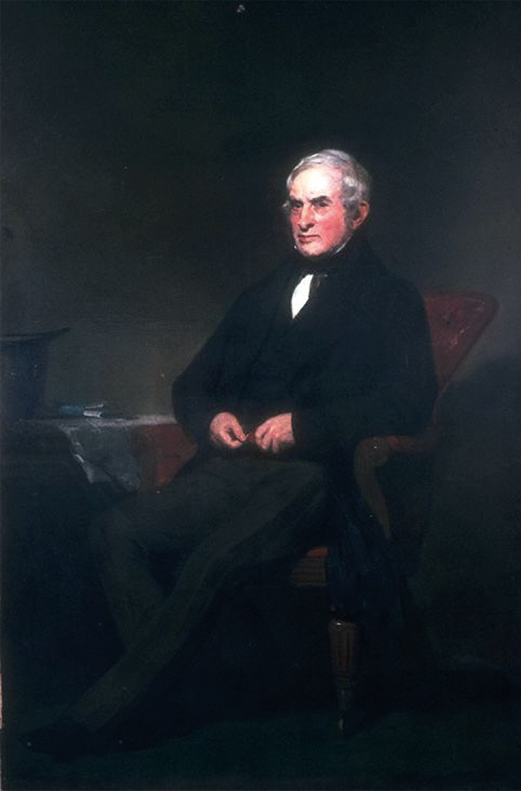

John Crawfurd, the second Resident of Singapore (1823–26) threatened to deny Sultan Hussein Shah and Temenggong Abdul Rahman of their allowances in order to get them to sign the 1824 Treaty of Friendship and Alliance that would strip them of their rights over the island. Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

John Crawfurd, the second Resident of Singapore (1823–26) threatened to deny Sultan Hussein Shah and Temenggong Abdul Rahman of their allowances in order to get them to sign the 1824 Treaty of Friendship and Alliance that would strip them of their rights over the island. Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.This 1824 Treaty of Friendship and Alliance replaced the agreement that Stamford Raffles, representing the EIC, signed with the Malay chiefs in 1819. Unlike the earlier agreement which only permitted the EIC to set up a trading post on the island, the Sultan and Temenggong now ceded “in full Sovereignty and property to the Honourable the English East India Company, their Heirs and Successors for ever, the Island of Singapore… together with the adjacent seas, straits, and islets to the extent of the ten geographical miles, from the coast of the said main island of Singapore”.

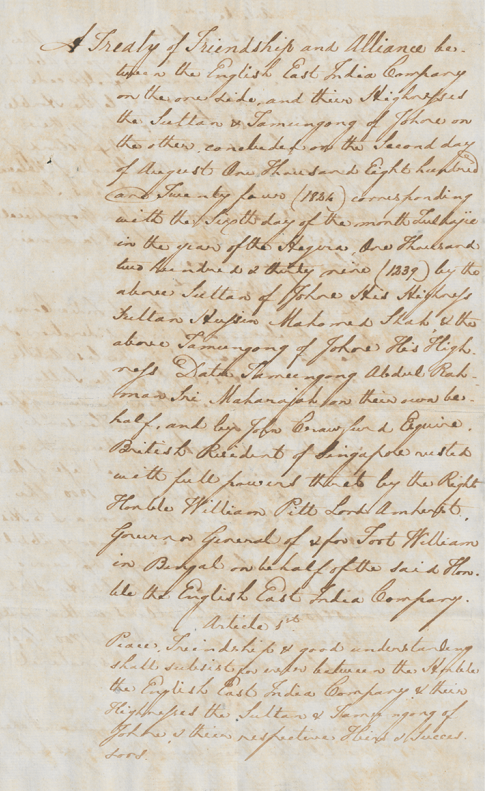

The 1841 copy of the original “Record of the Treaty of Friendship and Alliance, 2 August 1824” signed between John Crawfurd, the second Resident of Singapore (1823–26) and Sultan Hussein and Temenggong Abdul Rahman. This treaty replaced the 1819 document that Raffles signed with the Malay rulers, which only permitted the British to lease a two-mile stretch of land along the northern shore and allowed them to start a trading post, or “factory”, within its confines. With this 1824 treaty, Singapore was effectively ceded to the British in its entirety. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The 1841 copy of the original “Record of the Treaty of Friendship and Alliance, 2 August 1824” signed between John Crawfurd, the second Resident of Singapore (1823–26) and Sultan Hussein and Temenggong Abdul Rahman. This treaty replaced the 1819 document that Raffles signed with the Malay rulers, which only permitted the British to lease a two-mile stretch of land along the northern shore and allowed them to start a trading post, or “factory”, within its confines. With this 1824 treaty, Singapore was effectively ceded to the British in its entirety. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.The British could sign this new agreement in part because of the Anglo-Dutch Treaty that had been inked only months earlier, on 17 March 1824, which clearly demarcated the territorial interests of the British and their Dutch rivals in Southeast Asia. Following the ratification of this treaty, the Dutch withdrew their claims to Singapore and ceded Malacca to the British. In return, they gained sovereign control over Bencoolen (Bengkulu) and other British possessions in Sumatra.

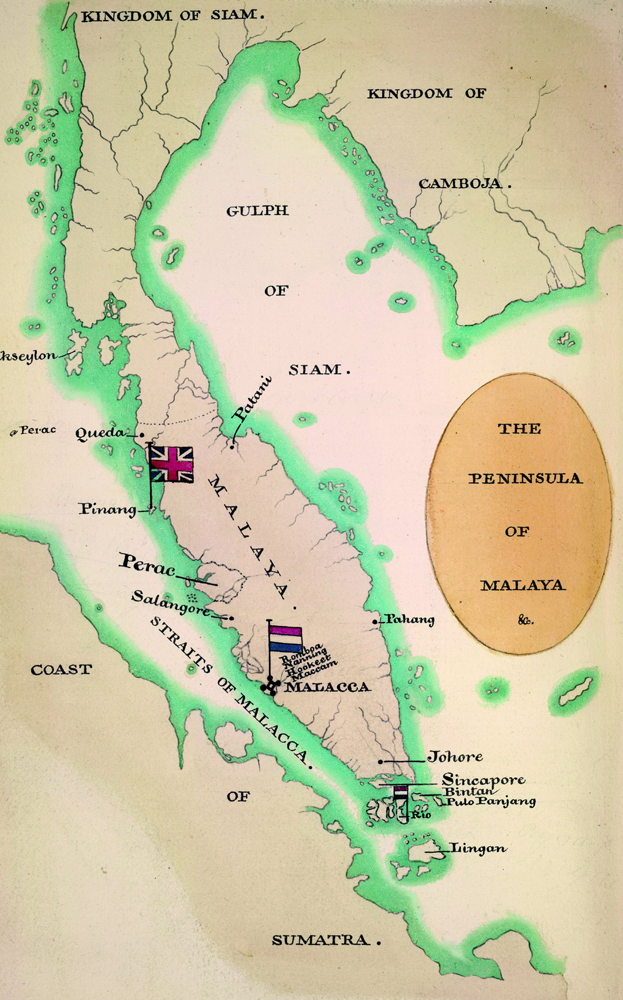

This map shows how the Malay Peninsula was divided between the British and the Dutch prior to the 1824 Anglo-Dutch Treaty. Malacca, which is flagged as Dutch, would eventually come under British rule upon the conclusion of the treaty. © The British Library Board (C11074002 IOR 1/2/1 Folio No. 345).

This map shows how the Malay Peninsula was divided between the British and the Dutch prior to the 1824 Anglo-Dutch Treaty. Malacca, which is flagged as Dutch, would eventually come under British rule upon the conclusion of the treaty. © The British Library Board (C11074002 IOR 1/2/1 Folio No. 345).Gaining sovereignty over Singapore gave the British a free hand in determining its future. In 1826, barely two years after the agreement was signed, Singapore, Penang and Malacca came to be ruled as the Straits Settlements, with English law introduced through a royal charter backed by the full authority of the British Crown. The charter provided the three territories with a proper and enforceable legal framework that would greatly facilitate growth in local commerce and trade.

However, the British held the view that Sultan Hussein and Temenggong Abdul Rahman were unsuitable partners in advancing Singapore’s further development. Under the terms of the first agreement, the three signatories – the EIC and the two Malay chiefs – shared power. However, the British felt that the authority shared with the Sultan and Temenggong were disproportionate in comparison with their contributions.

The Sultan and Temenggong were initially reluctant to sign the treaty as it would strip them of their sovereign rights over Singapore, which had been passed down from their ancestors. When they hesitated, Crawfurd held back their allowances until they agreed to sign the treaty three months later. The Malay chiefs relented as they had become dependent on the British for their monthly stipends and also needed British military protection from the Sultan of Riau who regarded Sultan Hussein as a usurper.

In exchange, the Sultan and Temenggong each received a lump sum of money, had their allowances increased, and were guaranteed due respect and personal safety in Singapore and Penang. A year after the treaty was concluded, Crawfurd sailed around Singapore to mark the anniversary of official British control over Singapore and its surrounding waters and islands. A 21-gun salute was also fired on Pulau Ubin to commemorate the event.

There were three original signed copies of the ratified 1824 treaty: one for the British India government, which is now archived with the British Library’s India Office collection, and the other two for the Sultan and Temenggong.1 The copy belonging to the National Archives of Singapore was created in September 1841 at the request of then Governor of the Straits Settlements Samuel George Bonham.

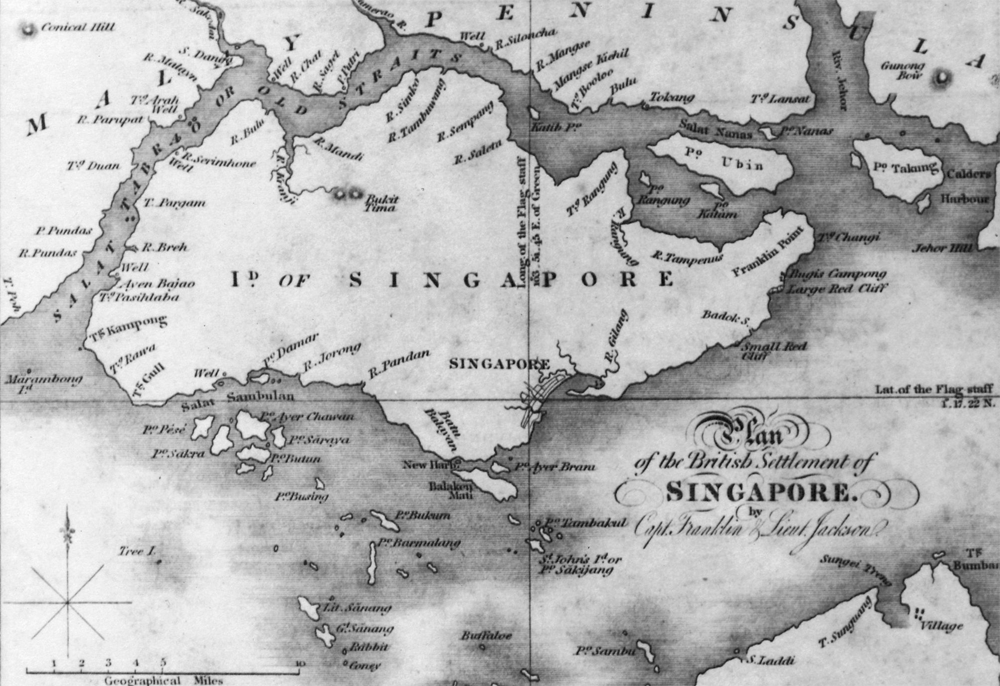

This map of Singapore was created using information gathered during John Crawfurd’s 10-day sail around the island after the conclusion of the Treaty of Friendship and Alliance in 1824. The map was published in his 1828 book, Journal of an Embassy from the Governor-General of India to the Courts of Siam and Cochin-China. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

This map of Singapore was created using information gathered during John Crawfurd’s 10-day sail around the island after the conclusion of the Treaty of Friendship and Alliance in 1824. The map was published in his 1828 book, Journal of an Embassy from the Governor-General of India to the Courts of Siam and Cochin-China. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Child Brides for Sale

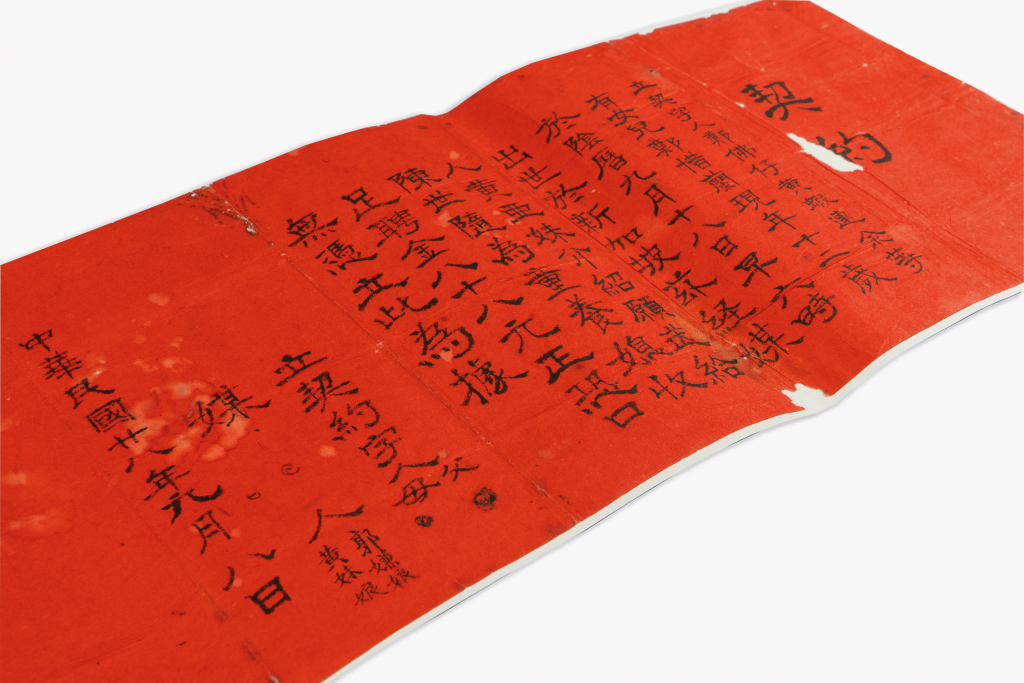

Title: 契约 Indenture of Selling Daughter

Source: Tan Boon Chong Collection, National Archives of Singapore

Year created: 1939

Type: Document

Accession no.: 135

Before the 1950s, it was common for impoverished Chinese parents in Singapore to sell their daughters as child brides, especially if they had too many children to feed. This relieved the parents of the expenses of raising another child, while the typically wealthy family who bought the child paid a lower dowry for the young bride-to-be and, at the same time, procured her services as a maid.2

This social practice of buying and selling young girls is documented in this contract (契约; qi yue) dated 8 September 1939. The girl in question is Tay Ai Lan (郑惜兰), a 12-year-old child bride (童养媳; tong yang xi), who was sold for a dowry of $88. The contract specifies her date of birth as the 18th day of the ninth lunar month. It also lists the names of her parents, the representative from the other family as well as the two matchmakers who witnessed the transaction.

契约 “Indenture of Selling Daughter”, 1939. This contract was made between the family of 12-year-old Tay Ai Lan who was “sold” for a dowry of $88 to a wealthy family. Tay ended up working as a domestic servant for the family she was indentured into – as many child brides did – before she married the second son in the family when she turned 18 years old. Tan Boon Chong Collection, courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore.

契约 “Indenture of Selling Daughter”, 1939. This contract was made between the family of 12-year-old Tay Ai Lan who was “sold” for a dowry of $88 to a wealthy family. Tay ended up working as a domestic servant for the family she was indentured into – as many child brides did – before she married the second son in the family when she turned 18 years old. Tan Boon Chong Collection, courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore.Child brides in Singapore were known by different dialect names: the Hokkiens referred to them as sim pu kia, while the Cantonese called them san po tsai. Both can be loosely translated as “little daughter-in-law”. Despite its namesake, the practice of child marriages was more accurately described as an adoption rather than a marriage, as the young girl usually worked as a domestic servant for the family before she finally got married to her intended husband.3

A contract, like the one for Tay, may have been drawn up to legally bind both parties to the betrothal until the girl reached puberty. However, a child bride might not eventually marry her intended husband for a variety of reasons, one of which could be his objection to the marriage.4 Fortunately in Tay’s case, she did go on to marry the second of three sons in the family when she turned 18. It was a union of “few dramatic ups and downs”, and the couple eventually had many children and grandchildren.5 Tay’s contract was donated to the National Archives of Singapore by her son Tan Boon Chong in 1991.

The practice of giving up an unwanted child for financial reasons was carried out not only in Singapore but also in rural communities in Hong Kong and other parts of Southeast Asia. In Singapore, child marriages continued to be practised until the mid-20th century by “debt-ridden, gambling, opium-smoking fathers or those who needed money to fulfill filial duties like paying for medical or funeral expenses for elderly parents”, noted Koh Choo Chin, a social worker in the Social Welfare Department in 1948.6 She observed that superstition was also one of the reasons why parents were willing to sell their daughters as child brides. To the Chinese, a girl born in the Year of the Tiger, for example, was believed to bring bad luck to the family.

Girls could be sold as child brides even while they were still babies or between the ages of nine and mid-teens. Compared with a typical bridal dowry, child brides cost significantly less. In the 1950s, the family of a child bride in Singapore was paid around $40, while regular brides received a dowry of between $150 and $200.7

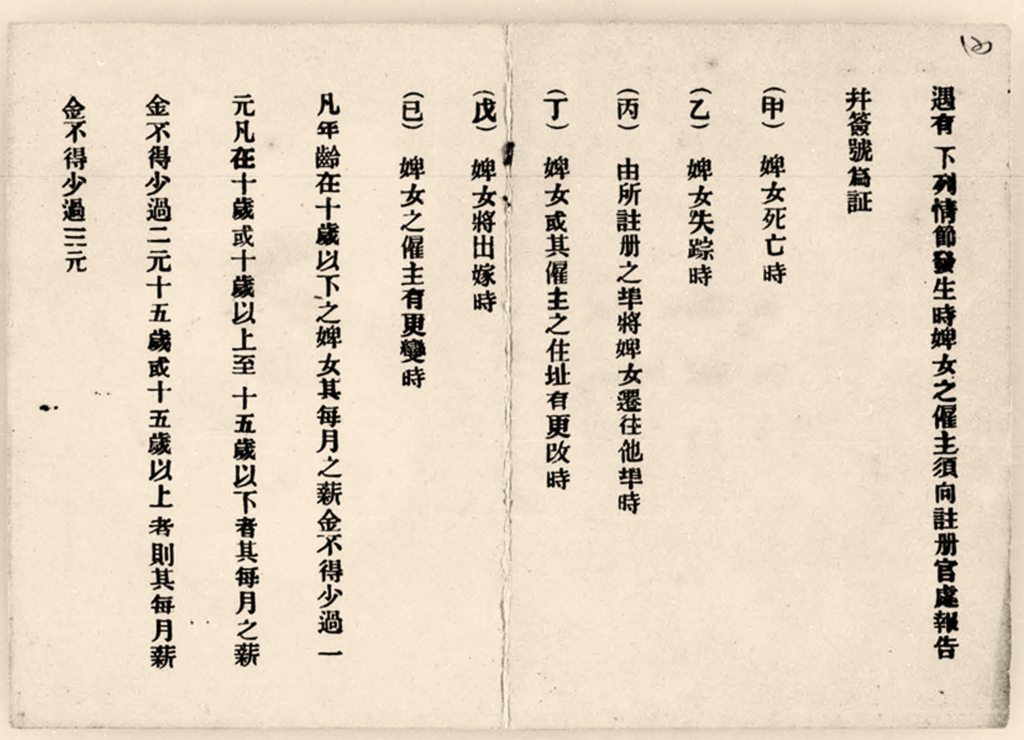

In those days, the practice of child marriage was often conflated with the mui tsai (“little sister” in Cantonese) system, in which young girls were sold to affluent Chinese families as domestic servants but without a pledge of marriage to a son of the family.8 As with child marriages, a document was drawn up between the two parties, and the girl would be transferred to the new household. All ties with her parents were cut once the purchase money was handed over.9

The practice of selling child brides is not to be confused with that of the mui tsai. Mui tsai (younger sister in Cantonese) were young girls who were sold as domestic servants to rich Chinese families. Child brides (or san po tsai in Cantonese), on the other hand, who were sold to Chinese families in return for a dowry, usually ended up marrying one of the sons of the family she was bought into. Pictured here is an identification card for a mui tsai issued by the Chinese Protectorate in 1932. The reverse of the card shows the terms and conditions that employers had to agree to upon registering their mui tsai. Lee Siew Hong Collection, courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore.

The practice of selling child brides is not to be confused with that of the mui tsai. Mui tsai (younger sister in Cantonese) were young girls who were sold as domestic servants to rich Chinese families. Child brides (or san po tsai in Cantonese), on the other hand, who were sold to Chinese families in return for a dowry, usually ended up marrying one of the sons of the family she was bought into. Pictured here is an identification card for a mui tsai issued by the Chinese Protectorate in 1932. The reverse of the card shows the terms and conditions that employers had to agree to upon registering their mui tsai. Lee Siew Hong Collection, courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore.While the British colonial government attempted to prohibit the acquisition of mui tsai through the 1932 Mui Tsai Ordinance, they did not attempt to push for similar legislation for child marriages.10 This document offers a rare glimpse into this social practice in 1930s Singapore.

The People’s Theatre

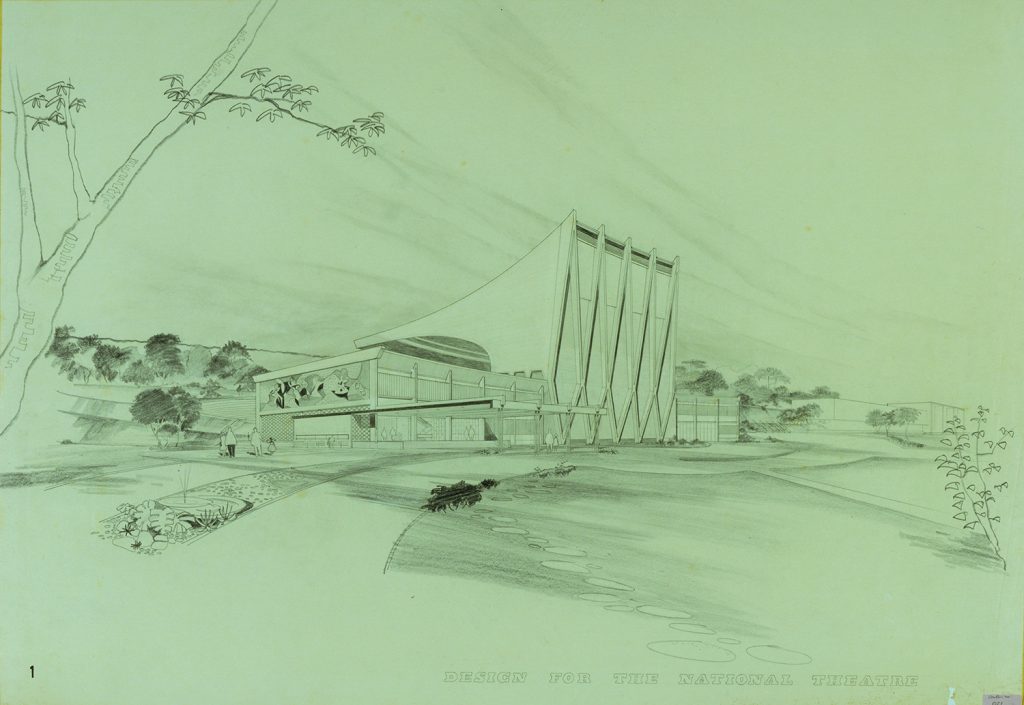

Title: Architectural Design Drawing of the National Theatre: Perspective View

Source: Alfred Wong Partnership Collection, National Archives of Singapore

Year created: 1960

Type: Architectural drawing

Accession no.: 19990003367 IMG0001

On the slopes of Fort Canning Hill, facing Clemenceau Avenue, once stood the iconic National Theatre, which was built to commemorate Singapore’s attainment of self-government in 1959.

At the theatre’s opening on 8 August 1963, Yang di-Pertuan Negara (Head of State) Yusof Ishak explained that the building was “dedicated to the ideal of a harmonious development of a diversity of cultures within the framework of national unity”.11

This architectural drawing shows the open-air theatre with its distinctive facade featuring five vertical diamond-shaped bays. A fountain was later erected outside the theatre in 1966. While these features have been said to symbolise the five stars and crescent moon on Singapore’s state flag respectively, its architect Alfred H.K. Wong has commented otherwise.

“Architectural Design Drawing of the National Theatre: Perspective View”, 1960. Alfred Wong Partnership Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

“Architectural Design Drawing of the National Theatre: Perspective View”, 1960. Alfred Wong Partnership Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.In actual fact, the building was designed such that the brick infill facade could structurally reinforce the back wall of the stage house. Wong arrived at this design as he wanted to avoid the use of a conventional rectangular grid. While the National Theatre Trust suggested adorning the diamond-shaped elements with national symbols of some kind, this did not happen in the end as Wong explained:

“Fortunately, no agreement came of this suggestion, as I’d much prefer to leave the brick work with its varied dark orange colour as a symbol of a material that was made out of the soil of Singapore.”12

The plan to build a national theatre that could provide cultural entertainment for the masses was first announced in 1959 by then Minister for Culture S. Rajaratnam. The theatre was subsequently dubbed the “People’s Theatre” as a third of its $2.2 million price tag came from public contributions. The funds were solicited through various donation drives, most notably the “a-dollar-a-brick” campaign.

Wong’s theatre design was selected through a competition. The theatre, with its open-air concept complemented by a cantilevered roof providing shelter for the overall structure, was described by the acclaimed ballerina Margot Fonteyn, who performed there in 1971, as the “perfect one for this sort of climate”.13 Wong would later design other prominent buildings such as Singapore Polytechnic and Marco Polo Hotel.

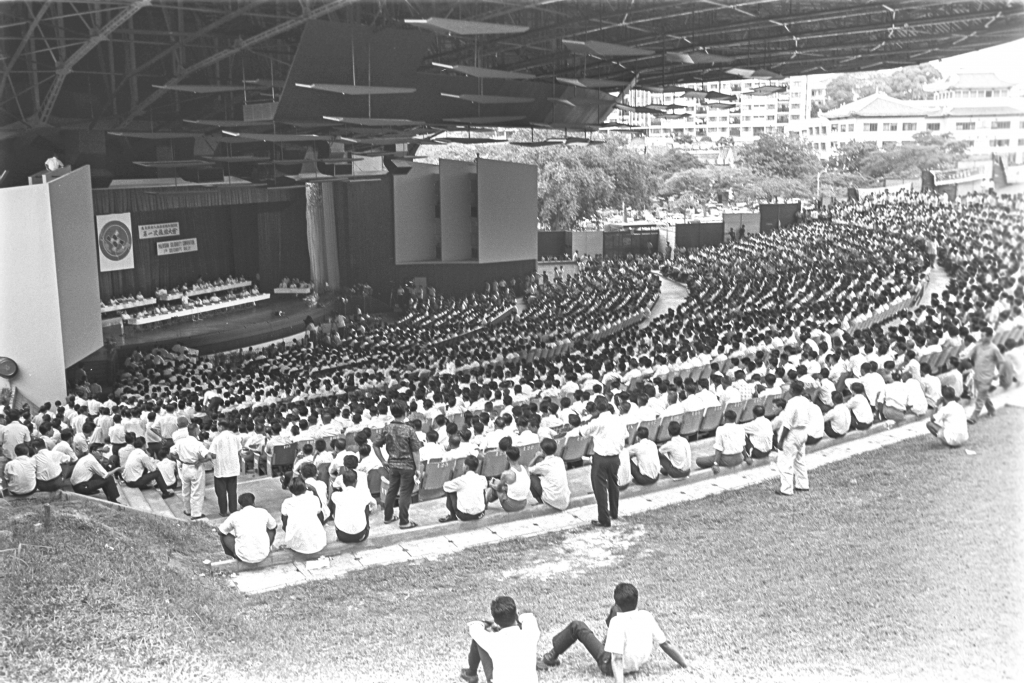

When the National Theatre officially opened on 8 August 1963, it was the largest theatre in Singapore with a seating capacity of 3,420. The theatre even had a revolving stage that cost $10,000 a year to maintain, although it was rarely put to use.

The first show performed at the theatre was the Southeast Asia Cultural Festival, and included performances by Cambodian royalty and Hong Kong film stars. Wong recalled that regional countries sent “their best” to the festival, which was touted as the “greatest show in the East”.14 He later said in an oral history interview in 2012:

The National Theatre, as seen during the 1965 Malaysian Solidarity Convention. The open-plan design of the theatre had a particular quirk; it allowed non ticket-holders perched on the hill outisde the theatre to watch the events for free. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The National Theatre, as seen during the 1965 Malaysian Solidarity Convention. The open-plan design of the theatre had a particular quirk; it allowed non ticket-holders perched on the hill outisde the theatre to watch the events for free. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.“I tell you, it was unforgettable. I mean, for me it was like the experience of my life because when the curtains opened – I mean – you had [a] full house, you had probably about 8,000 behind in the open air all clapping and yelling away. You know, it was tremendous. I mean – I’ve never seen an audience react to that.”15

The festival was held in the theatre even though it had yet to be completed. A canvas was put up where the roof was still unfinished – and Wong noted that “(at) night time when it’s all lit up, it was all right”.16

Over the next two decades, the National Theatre hosted various national and cultural events. These included National Day Rallies (1966–82), university convocations as well as performances by world-famous names, such as the British pop group Bee Gees and the Sadler’s Wells Royal Ballet.

Popular events were sometimes “attended” by more than just ticket-holders, as the theatre’s location at the base of Fort Canning Hill allowed people to position themselves strategically on the hillside above the building to enjoy the same events for free. The theatre’s open-air design also invited complaints about noise from passing traffic, inadequate shelter from heavy rain, and the presence of rats, bats and cockroaches.

The National Theatre was demolished in 1986 amid concerns that the building was structurally unsafe. The government also had plans to construct an expressway nearby, which eventually became part of the Central Expressway.

Despite its demolition, the Ministry of Culture noted that the National Theatre had played an important part in nation-building by inculcating “a spirit of self-help and a sense of nationhood”. In 2000, the location of the National Theatre was declared a historic site by the National Heritage Board.17

This essay is reproduced from the book 50 Records from History: Highlights from the National Archives of Singapore. It features 50 short essays written by archivists on selected records from the archives that commemorate major milestones in Singapore’s history. The book is available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries (Call nos.: RSING 959.57 HUA-[HIS]and SING 959.57 HUA-[HIS]).

The three historical records covered in this essay were written by Kevin Khoo, Fiona Tan and Yap Jo Lin respectively. Kevin is an oral history specialist, while Fiona and Jo Lin are archivists. All three work at the National Archives of Singapore.

Fiona Tan is an Archivist with the Outreach Department, national Archives of Singapore where she conducts research to promote a greater awareness of its collections.

Fiona Tan is an Archivist with the Outreach Department, national Archives of Singapore where she conducts research to promote a greater awareness of its collections.

Kevin Khoo is an Archivist at the National Archives of Singapore. His current responsibilities include archival research and content development.

Kevin Khoo is an Archivist at the National Archives of Singapore. His current responsibilities include archival research and content development.

Yap Jo Lin is an archivist in NAS’ Archives Services Department. She handles NAS’ collection of building plans, as well as government speeches and press releases.

Yap Jo Lin is an archivist in NAS’ Archives Services Department. She handles NAS’ collection of building plans, as well as government speeches and press releases.

NOTES

-

Crawfurd, J. (1824). Letter from Resident John Crawfurd to Governor-General of India in Council, Singapore, 1 October 1824. In Government of the Colony of Singapore, Straits Settlements Records. Series M. Singapore: Letters from Bengal to the Resident. Singapore: Government of the Colony of Singapore. (Microfilm nos.: NL59–62) ↩

-

Freedman, M. (1957). Chinese family and marriage in Singapore (pp. 66–67). London: HMSO. (Call no.: RSING 301.42 FRE) ↩

-

Lim, O. (1991, March 14). Sold as a bride for $88. The New Paper, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Koh, C. C. (1994). Implementing government policy for the protection of women and girls in Singapore 1948–1966: Recollections of a social worker (p. 129). In M. Jaschok & S. Miers (Eds.), Women and Chinese patriarchy: Submission, servitude, and escape. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. (Call no.: RSING 305.420951 WOM) ↩

-

Miers, S. (1994). Mui tsai through the eyes of the victim (p. 111). In M. Jaschok & S. Miers (Eds.), Women and Chinese patriarchy: Submission, servitude, and escape. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. (Call no.: RSING 305.420951 WOM) ↩

-

Sam, J. (1963, August 9) The first 1,500. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Wong, A. (2016) The story of the People’s Theatre (pp. 33–57). In C.K. Lai (Ed.), Recollections of life in an accidental nation. Singapore: Select Publishing. (Call no.: RSING 720.92 WON) ↩

-

Oon, V. (1971, November 4). ‘First lady’ of ballet praises theatre. New Nation, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Tyers, R. K., & Siow, J. H. (1993). Ray Tyers’ Singapore: Then & now. (p. 155). Singapore: Landmark Books. (Call no.: RSING q959.57 TYE) ↩

-

Lim, P. H. L. (2009). Chronicle of Singapore: Fifty years of headline news 1959–2009 (p. 62). Singapore: Didier Millet in association with National Library Board. (Call no.: RSING 959.5705 CHR) ↩

-

Jay, S.E. (Interviewer). (2012, February 8). Oral history interview with Alfred Wong Hong Kwok [MP3 recording no. 003689/9/7]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Oral history interview with Alfred Wong Hong Kwok, 8 Feb 2012. ↩

-

National Theatre location a historic site now. (2000, February 1). The Straits Times, p. 32. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩