Pioneers of the Archives

Fiona Tan tells us about the people who laid the bedrock of the National Archives of Singapore, along with details of how the institution has evolved since its inception in 1938.

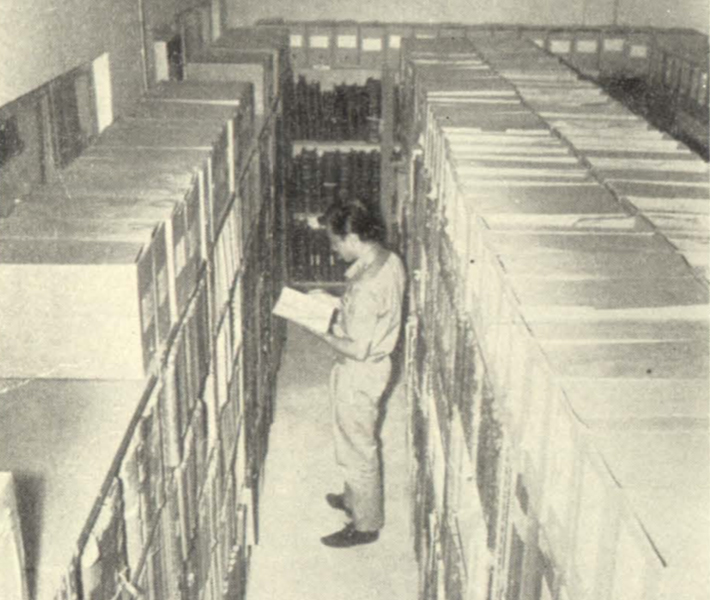

A staff sorting records at the repository in the Lewin Terrace premises of the National Archives and Records Centre (NARC) in 1970. Image reproduced from Annual Report of the National Archives and Records Centre 1970.

A staff sorting records at the repository in the Lewin Terrace premises of the National Archives and Records Centre (NARC) in 1970. Image reproduced from Annual Report of the National Archives and Records Centre 1970.“The man who is appointed to a post being created by the Straits Settlements Government will have a life-time job before him. An archivist is wanted.”1

In April 1938, an advertisement to recruit the first archivist for the Raffles Museum and Library was placed in The Straits Times, describing the position – with typically dry British wit – as a “life-time job”. One can assume that this phrase was not in reference to the permanent nature of the job, but to the scale and difficulty of the tasks that awaited the person who eventually filled the position.

Since then, many brave and dedicated persons have played a part in preserving Singapore’s history through their work as pioneering archivists and early supporters of the archives.

The First Archivist: Tan Soo Chye

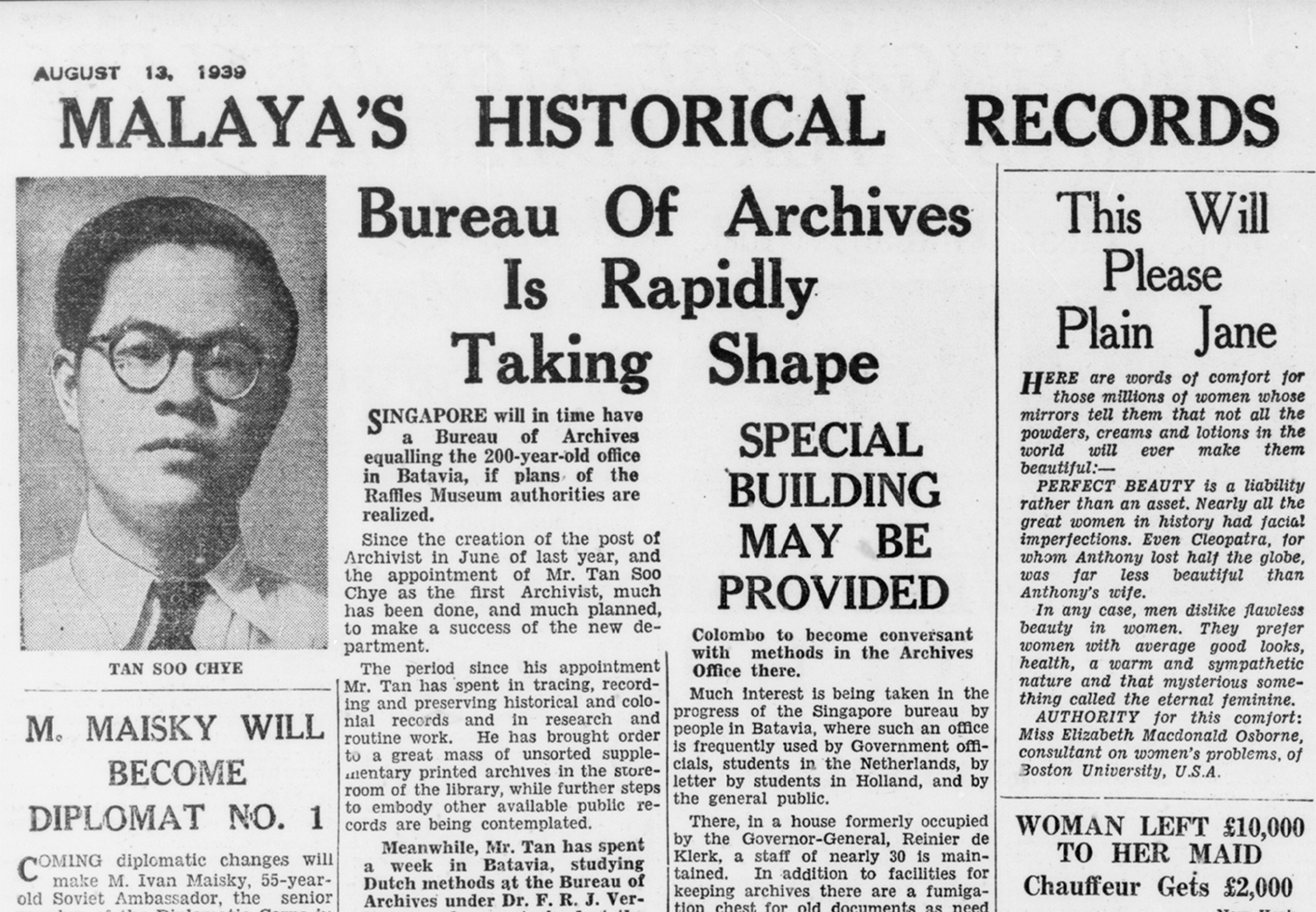

The man eventually selected as Singapore’s first archivist was Tan Soo Chye, a fresh graduate from Raffles College. Shortly after his appointment at the archives unit under the Raffles Museum and Library, the 24-year-old left for Batavia (present-day Jakarta) to study under Frans Rijndert Johan Verhoeven, the Landsarchivaris (National Archivist) of the Lands Archief te Batavia (State Archives of Batavia) in Java for two weeks. The Raffles Museum and Library was then located on Stamford Road, in the building that today houses the National Museum of Singapore.

Upon his return, Tan began indexing the Straits Settlements Records (SSR), a series of 170 large bound volumes of handwritten records from as early as 1800 that document the British administration of the Straits Settlements comprising Singapore, Penang and Malacca. These records had been recently transferred from the library of the Colonial Secretary to the care of the Raffles Museum and Library.2 By 1940, Tan had compiled a “comprehensive index recording every person, event and institution mentioned in original documents of all records relating to the Straits Settlements” in the series.3

Tan Soo Chye, the first archivist appointed by the Straits Settlements government in 1938 to manage the historical records at the archives office at the Raffles Museum and Library. Image reproduced from The Straits Times, 13 August 1939, p. 13.

Tan Soo Chye, the first archivist appointed by the Straits Settlements government in 1938 to manage the historical records at the archives office at the Raffles Museum and Library. Image reproduced from The Straits Times, 13 August 1939, p. 13.Soon after the outbreak of World War II in Malaya in 1941, the records were sent to the Raffles College for safekeeping.4 Edred J.H. Corner, the botanist responsible for the care of the remaining books and specimens in the Raffles Museum and Library during the Japanese Occupation, wrote a vivid account of how some of these records came back to the library’s possession – first through a passive, but incomplete, return from the Syonan Department of Education in February 1944, and later by a chance discovery and subsequent swift purchase of several missing volumes that were being sold as wastepaper by unknowing Chinese women labourers.5

After the war, Tan returned to his job as the sole archivist. He began to promote the SSR collection by writing articles on Singapore’s history for various newspapers, giving public talks on local history, and publishing essays about the SSR in academic journals, including the esteemed Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. Michael Tweedie, then Director of the Raffles Museum and Library, began exploring ways to provide Tan with opportunities for further study and professional development.6 Tan eventually obtained a Class II honours in history from the University of Malaya in 1951 and graduated at the same time as Hedwig Aroozoo (later Hedwig Anuar, the first director of the National Library).7

In December 1953, an unexpected turn of events saw Tan transferred to the Department of Customs and Excise. There, Tan rose rapidly through the ranks to become Comptroller of Customs in 1960, the first Asian to do so. Tan later served as a member of the National Archives and Records Committee, albeit for a short period, from 1975 to 1976, to advise the National Archives and Records Centre on what records to acquire and review as a representative of the Joint Chambers of Commerce.8

Historians Call for a National Archives

With Tan’s departure, the position of archivist remained vacant until 1967. Upon the separation of the Raffles Library and Museum in 1955, the archives unit became a department under the Raffles Library. In 1958, the Raffles Library was renamed Raffles National Library, moving two years later into the now-demolished red-brick building at the other end of Stamford Road and changing its name yet again – this time to just the National Library. All this while, the archives was under the charge of the library. During this period, reference librarians continued to provide administrative support and helped researchers with their requests, even though they had no experience in managing archival records.9

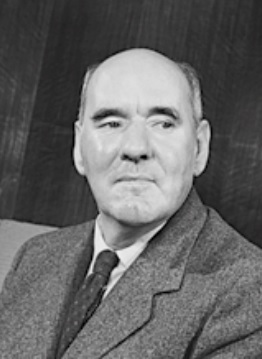

One of the earliest public calls for an independent archives came from Cyril Northcote Parkinson, Head of the Department of History at the University of Malaya. In 1953, he issued a strongly worded editorial in The Straits Times, titled “Lumps are Being Eaten Out of Our History: Cockroaches Make Past a Mystery”, in which he recommended setting up a national archives where “in air-conditioned rooms, on steel shelves, with skilled supervision and proper precaution against fire and theft, the records of Malayan history might be preserved indefinitely”.10

Cyril Northcote Parkinson, Head of the Department of History at the University of Malaya. He was one of the earliest to call for a national archives to be established in Singapore. This portrait was taken in 1961. Source: National Archives of The Netherlands, retrieved from Wikimedia Commons.

Cyril Northcote Parkinson, Head of the Department of History at the University of Malaya. He was one of the earliest to call for a national archives to be established in Singapore. This portrait was taken in 1961. Source: National Archives of The Netherlands, retrieved from Wikimedia Commons.In 1956, Parkinson reiterated his view, which had now taken on a nationalist urgency, asserting that “one early sequel to Merdeka should be the creation of a Malayan National Archives”.11 His view was echoed by Kennedy Gordon Tregonning, a history lecturer at the university, who urged for archival and records management legislation to ensure that the past will be “preserved for the historians (and the administrators) of the future”.12

While an archives was set up in the Federation of Malaya in 1957, Singapore continued to be without an independent archival institution. Tregonning, who succeeded Parkinson as head of the University of Malaya’s history department in 1959, continued advocating for a national archives in Singapore.13 During a visit to the Toyo Bunko14 in Tokyo, Japan, in 1966, he saw a collection of East Asian manuscripts printed on bamboo strips which inspired him further. Upon his return, he helped Hedwig Anuar, Director of the National Library, to draft a proposal to establish an archives institution in Singapore.15

Recommendation by UNESCO

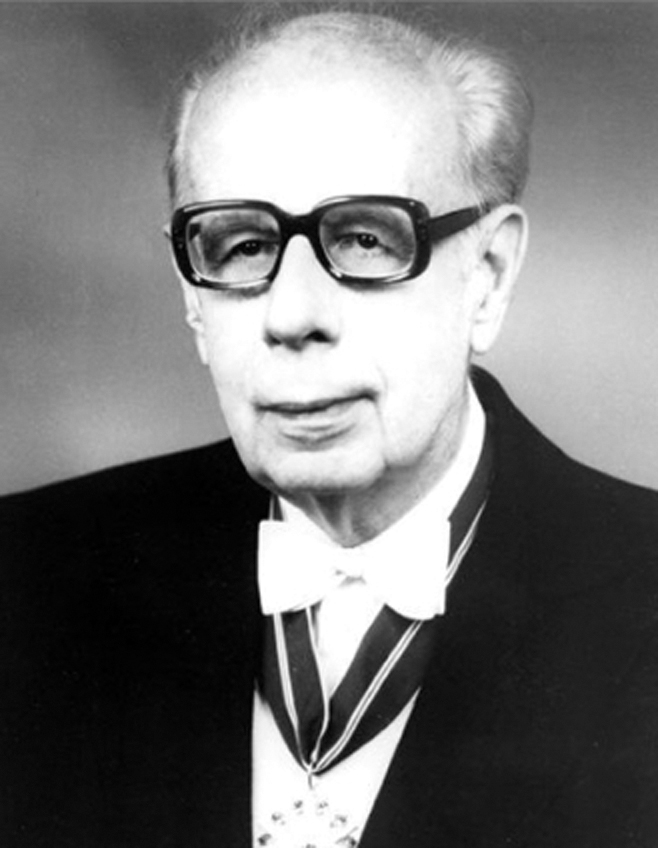

In February 1967, the Singapore government approached the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) for technical assistance to set up a national archives. UNESCO assigned the aforementioned Dutch archivist Frans Rijndert Johan Verhoeven, who had just completed a stint as the Director-General of the National Archives of Malaysia from 1963 to 1966.

Dutch archivist Frans Rijndert Johan Verhoeven advised the Singapore government on the best international practices on archives management and assisted in drafting related legislation, which eventually became the National Archives and Records Centre Bill. Image reproduced from Web Centre for the History of Science in the Low Countries.

Dutch archivist Frans Rijndert Johan Verhoeven advised the Singapore government on the best international practices on archives management and assisted in drafting related legislation, which eventually became the National Archives and Records Centre Bill. Image reproduced from Web Centre for the History of Science in the Low Countries.Between April and August 1967, Verhoeven advised the Singapore government on the best international practices on archives management and assisted in drafting related legislation, which would eventually become the National Archives and Records Centre Bill. Verhoeven also conducted an extensive survey of records and archives held at the National Library and at other government agencies. He found that there was no systematic method for appraising records among the government ministries and statutory boards he surveyed, and that only three departments had been transferring records since 1959. He also recommended halving the time that public records were kept restricted, from 50 to 25 years, and having archives staff, rather than administrative officers, be responsible for appraising records.

Furthermore, Verhoeven found that the pre-war records held by government departments were in a much worse state, as they had been “stored on wooden shelves and cupboards, a victim of the rigours of the tropical climate, of the continuous attacks of voracious insects and rodents, and liable to moulding and foxing from dampness and flooding”. There was “no air-conditioning, fumigation nor repair”, and the precious records were at risk from fire and flooding. Verhoeven anticipated an urgent need for additional space to accommodate both new and existing records.

In addition, Verhoeven reviewed the archives’ existing holdings and concluded that there was much material “of historical value for the region”. He lamented, however, over the severely inadequate storage facilities and handling of the collections. For example, the National Library, which fumigated the documents twice a year, did not have “the staff, the equipment nor the know-how to give these unique and important documents the treatment they urgently need[ed]”. There were also inadequate descriptions, indices and lists of the holdings to aid research and access.

Verhoeven’s findings and recommendations were documented in a highly influential report, Singapore: The National Archives and Records Management, published by UNESCO in December 1967 and presented to the Singapore government in February 1968. In the document, Verhoeven underscored the importance of a national archives to Singapore’s growth as a nation: “Perhaps I should stress here, that no people can be deemed masters of their own history until their public archives, gathered, preserved and made available for public inspection and investigation, have been systematically studied and the importance of their contents determined. Therefore, it is a moral obligation of any democratic government to make archives of national and historical value available to the people.”16

The report prepared by Dutch archivist Frans Rijndert Johan Verhoeven on the state of Singapore’s archives and records management practices. Titled Singapore: The National Archives and Records Management, it was published by UNESCO in December 1967 and presented to the Singapore government in February 1968.

The report prepared by Dutch archivist Frans Rijndert Johan Verhoeven on the state of Singapore’s archives and records management practices. Titled Singapore: The National Archives and Records Management, it was published by UNESCO in December 1967 and presented to the Singapore government in February 1968.The First Archives Director: Hedwig Anuar

In September 1967, Singapore’s parliament passed the National Archives and Records Centre Act, which established the National Archives and Records Centre (NARC) under the Ministry of Culture. The legislation empowered the NARC to operate as a separate national institution and to take over the management of archives and government records from the National Library. Its new statutory powers included the critical provision that public records could now only be destroyed or disposed on the authority of the NARC director. On 7 February 1969, Hedwig Anuar became the first director of the NARC; she was concurrently director of the National Library.

Under Anuar’s leadership, the NARC rapidly built up its institutional infrastructure and capabilities. In January 1970, partly in response to its perennial problem of insufficient space, the NARC moved to bigger premises, taking over two refurbished colonial houses at 17–18 Lewin Terrace, Fort Canning Hill. The new facility had space for more materials to be stored, more staff to be hired, and new equipment and services to be introduced. It was also furnished with a 24-hour air-conditioned repository.

Mrs Hedwig Anuar (extreme left) with then Minister for Culture S. Rajaratnam at the presentation ceremony of the Gibson-Hill Collection to the National Library, 1965. Courtesy of National Library Board.

Mrs Hedwig Anuar (extreme left) with then Minister for Culture S. Rajaratnam at the presentation ceremony of the Gibson-Hill Collection to the National Library, 1965. Courtesy of National Library Board.Despite this, the archives’ collections continued to grow so rapidly that the institution expanded into four buildings by mid-1973, including a third facility beside 17–18 Lewin Terrace, operational by mid-1971; and a Records Centre at 45 Minden Road in Tanglin, which opened in 1973.17

In the early years, establishing the paper conservation department was a priority as the NARC had an enormous volume of paper records that urgently needed care from years of neglect. Hence, the paper binding and repair section, the predecessor of today’s Archives Conservation Lab, was set up in July 1970.18

Besides overseeing the NARC’s development, Anuar also led the institution in establishing ties with other archival institutions in the region. In 1969, the NARC joined the Southeast Asian Regional Branch of the International Council on Archives (SARBICA), which had been established the previous year. Anuar also contributed to a greater regional awareness of archival resources in Singapore, presenting a paper in April 1969 on the National Library and NARC’s research resources on Southeast Asia at the SARBICA conference held in Puncak, Indonesia.19 She also served as the vice-chairman of SARBICA’s executive board between 1971 and 1973, and as its chairman from 1973 to 1975.20

Anuar held the position of director of the NARC until 7 February 1978, when a senior archives officer took over as acting director.

The First Professional Archivist: Lily Tan

In September 1967, Lily Tan left Singapore to pursue her studies in archives administration at the University College London under a Colombo Plan Scholarship.21 Upon her return and appointment as senior archives officer in late August 1968, the NARC officially began operations with a skeletal staff of eight people: Tan, two clerical assistants, two archives attendants, a typist, a binder and an office assistant.

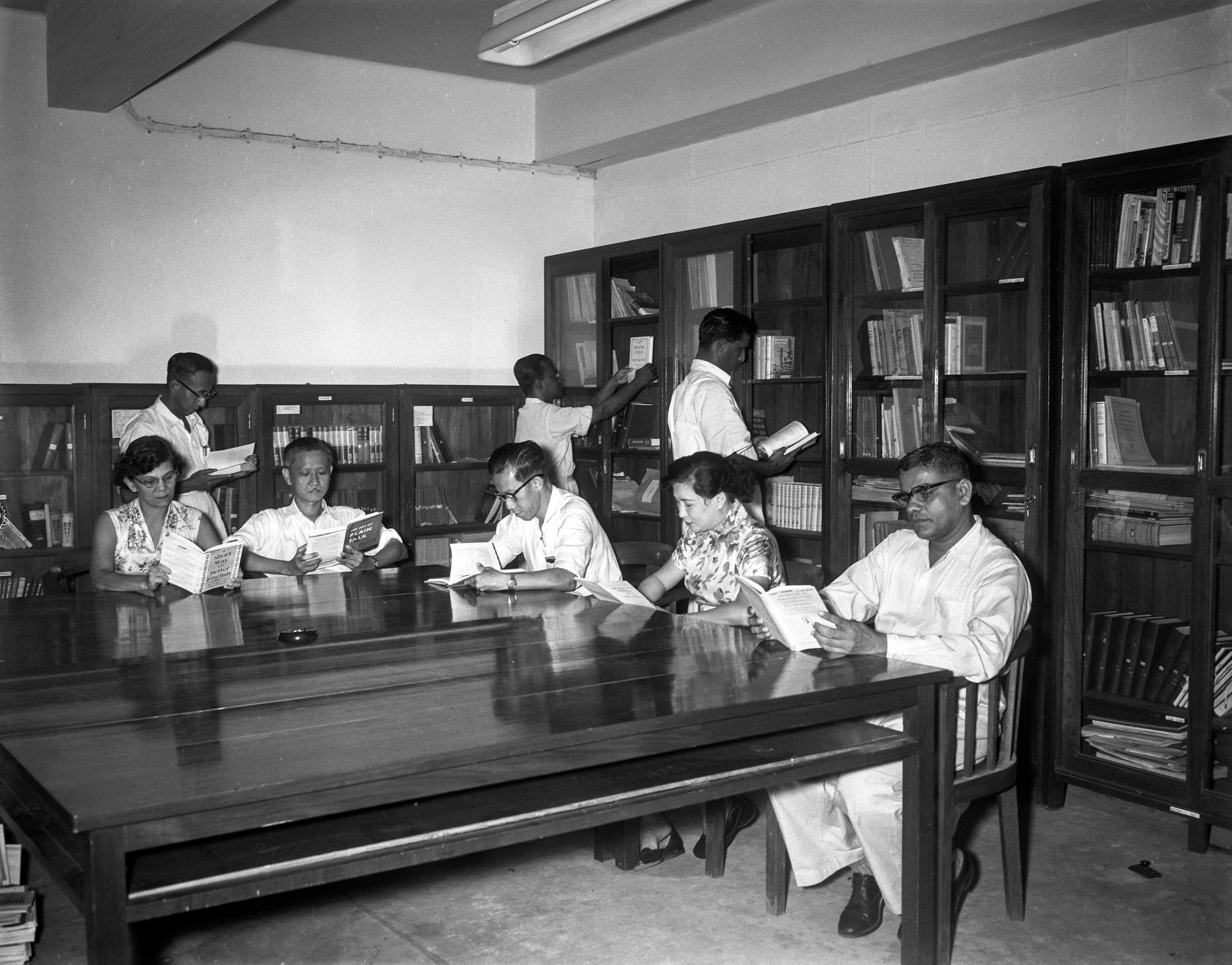

Staff of the Raffles Library photographed in 1957. Between 1954 and 1967, the archives was a department under the Raffles Library, later renamed as the National Library. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Staff of the Raffles Library photographed in 1957. Between 1954 and 1967, the archives was a department under the Raffles Library, later renamed as the National Library. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Ten years later, in 1978, Tan was promoted to acting director. In 1985, she became NARC’s director, and would lead the institution for over two decades until her retirement in 2001 – the institution’s longest-serving director to date.

One of Tan’s first major tasks as acting director was to draft a memorandum for the establishment of an oral history programme within the NARC. The setting up of a national-level oral history programme to document histories that were not found in official records had the strong support of several influential members of government. While the idea was first mooted by then Deputy Prime Minister Goh Keng Swee in 1978, it was the permanent secretary in the Ministry of Finance, George Edwin Bogaars, who played an instrumental role in securing high-level support from his superiors and the Ministry of Culture.22

The proposal was quickly approved and the Oral History Unit began operations in September 1979, with Lily Tan concurrently holding the position as director of the newly formed unit. At the beginning of 1981, the Oral History Unit merged with the NARC to form the Archives and Oral History Department (AOHD), with Tan again serving as the director of the new entity.

In 1985, the AOHD was split into the Oral History Department – which came under the charge of Kwa Chong Guan, a senior Ministry of Defence officer who had been seconded to the Ministry of Culture – and the National Archives with Tan continuing as director, resuming its traditional role as the custodian of national records.23

Tan also oversaw the enhancement of the archives’ capabilities in preserving records. These plans included managing the Central Microfilm Unit (CMU) after it was transferred to the AOHD from the National Library in 1983.24 Starting in 1995, the archives began to emphasise the importance of managing electronic records. As Tan explained: “If we fail to manage electronic records, there will be gaps in our history.”25 These early initiatives in 1999 to develop guidelines on the archiving of e-mail records for the government and custom archival systems, such as the Electronic Registry System, continue to evolve and remain very relevant today.

Lily Tan, Director of the National Archives of Singapore (1978–2001), at the opening of the exhibition “Road to Nationhood” in 1984. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Lily Tan, Director of the National Archives of Singapore (1978–2001), at the opening of the exhibition “Road to Nationhood” in 1984. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Next, to improve access to its collections, the NAS launched an ambitious scheme to digitise its reference system in 1996. This meant painstakingly converting the archive’s hardcopy finding aids into an online digital database. Beginning with Picture Archives Singapore (PICAS) in 1998, which provided access to the archives’ extensive photo collection, it grew into a full-scale online database called Access to Archives Online (a2o) in July 2000.26 This was the precursor to today’s Archives Online database, which contains public listings of more than a million records. Technological advancements have also enabled the NAS to offer more records and of higher resolution on Archives Online, realising the vision of an archive that is accessible from home.

In April 1995, the Audiovisual Archives Unit was established within the NAS to collect, preserve and provide access to audiovisual records of national or historical significance. In the beginning, the collection comprised some 8,000 motion picture film reels and videotapes, which had been created by public offices, private organisations and individuals.27 The NAS also became a founding member of the Southeast Asia-Pacific Audio Visual Archives Association (SEAPAVAA), established in February 1996 in Manila, the Philippines, to bring together ASEAN film and video archivists. Today, SEAPAVAA is the leading audiovisual archive association in the Asia-Pacific region.

Building Awareness

Under Tan’s leadership, the National Archives embarked on several initiatives – mainly exhibitions and publications – to generate greater public awareness of its collections and services.28 Besides engaging traditional users, such as “people conducting historical research”, the NAS also cultivated new users, for instance, through dialogue sessions with arts practitioners.29

Like her predecessor Hedwig Anuar, Tan also saw the importance of establishing good relations with archives outside of Singapore. She played a leading role in SARBICA’s executive board, serving as its secretary general (1978–81), vice-chairman (1981–84; 1997–99), chairman (1984–87; 1999–2002) and executive board member (1987–95).30

Led by Tan, Singapore hosted high-profile regional and international archives-related seminars. One of these was the SARBICA seminar on the Management of Architectural and Cartographic Records in November 1991, a significant forum for dialogue between professionals across Southeast Asia, including archivists, librarians and professionals from other disciplines, such as urban planners, architects and conservation experts.31 Another was the IASA-SEAPAVAA Conference 2000, a major international conference hosted in conjunction with the International Association of Sounds and Audiovisual Archives (IASA) and SEAPAVAA. More than 190 leading archive professionals from 40 countries attended this event.32

In 1993, Tan led the National Archives through a major restructuring exercise, which saw the amalgamation of the National Archives, Oral History Department and National Museum into a new statutory board, the National Heritage Board (NHB). Under the NHB, the National Archives and Oral History Department came together once again to become a single unit called the National Archives of Singapore, with the Oral History Department renamed the Oral History Centre. The NHB was tasked to preserve and showcase Singapore heritage across all mediums and to increase public awareness and appreciation of Singapore’s past.

Accordingly, NHB’s public outreach efforts were stepped up, with almost 40 NAS exhibitions curated between 1996 and 2011 at high-traffic locations islandwide, including schools, community hubs and shopping centres. One high profile project was “The Singapore Story: Overcoming the Odds”. Launched in 1998 and curated by the Singapore History Museum (now National Museum of Singapore), the travelling national education exhibition and accompanying programmes, which featured archival materials from the NAS’ extensive collection, attracted a record 648,000 visitors. To complement the exhibition, NAS published the book Singapore: Journey to Nationhood, which enjoyed a record print run of over 27,000 copies and was subsequently translated into Chinese, Malay and Tamil.33

During Tan’s tenure as director, the archives relocated twice. The first was in 1984 to the refurbished Old Hill Street Police Station when it was still known as the Archives and Oral History Department. The new space had a substantially larger archival repository, a professional conservation and repair workshop, a microfilming lab, an exhibition space, a lecture hall and a large public reference room.34

In 1997, the archives moved again to a building it could finally call its own – the former Anglo-Chinese Primary School at 1 Canning Rise. Designed to encourage public visits to the archives, the building was renovated to include an Archives Reference Room, an enlarged exhibition area, a theatre and soundproof audio recording rooms. The new premises also came with five purpose-built climate controlled repositories and large workspaces for the archives’ conservation and imaging laboratories, ideal for both archival work and public tours.35

More recently, in April 2019, the NAS building reopened after an extensive 18-month renovation programme that saw upgraded facilities, expanded public spaces and a dedicated theatre for the screening of Asian film classics.

Building on Pioneers’ Work

Retiring from a long and illustrious career in the archives in 2001, Lily Tan handed over the baton to her successor. Many of her initiatives have been continued by subsequent directors of the National Archives of Singapore: Pitt Kwan Wah (2001–11), Eric Tan (2011–13), Eric Chin (2013–17) and Wendy Ang (2017–).

The pioneering officers who charted the course of the archives worked with a dependable team of staff, board members, government officials and public advocates who helped lay the foundation for many of the key programmes to acquire, preserve and disseminate records of national or historical significance.

The NAS has progressed a long way from its origins as a small archives unit in the Raffles Museum and Library in 1938. From a collection of just 170 Straits Settlements Records, the NAS has grown to become the trusted repository of a vast and growing multimedia collection of over 10 million records. It has become an archive of international standing today, and stands head and shoulders among the leading archival institutions of the world.

INSIGHTS FROM A VETERAN ARCHIVIST

Mrs Kwek-Chew Kim Gek has spent the last 45 years at the National Archives of Singapore (NAS). Besides her wealth of institutional knowledge, Mrs Kwek holds the record of being its longest-serving staff. She retired as Deputy Director (Records Management) in 2014 and currently works part-time as a senior archivist. She relates some of her experiences:

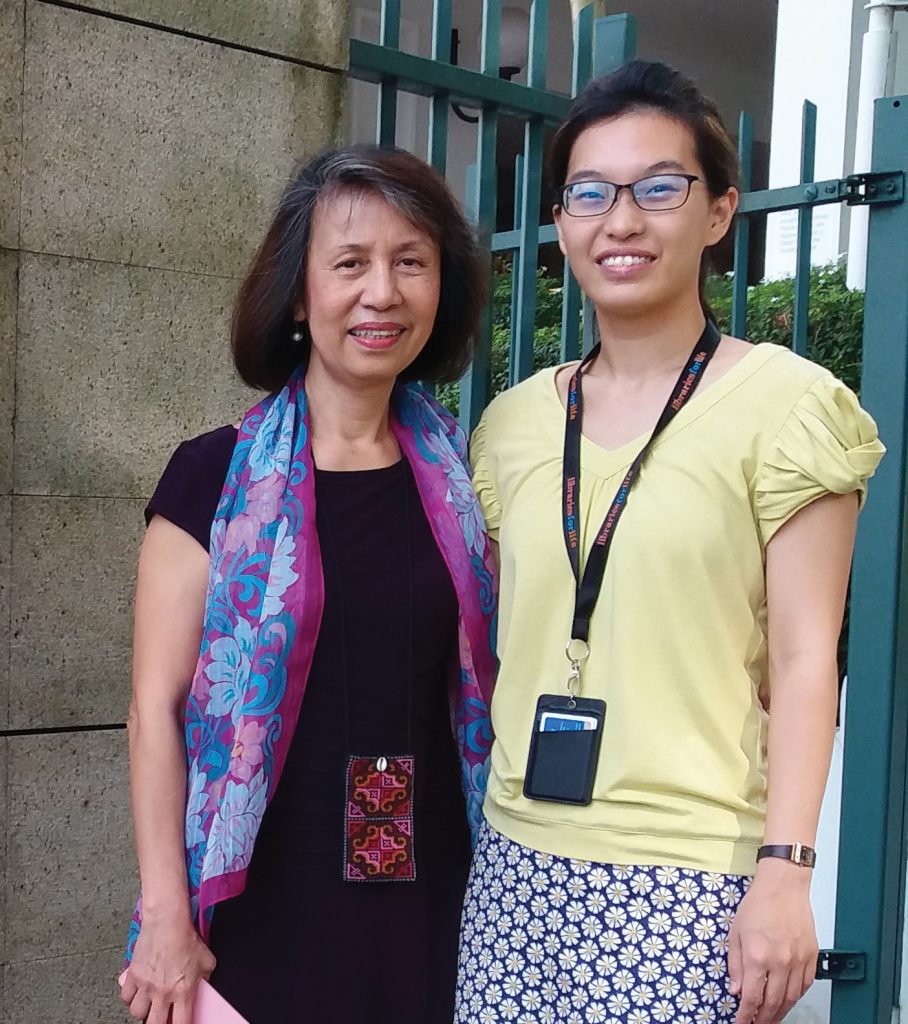

Mrs Kwek-Chew Kim Gek (left) with colleague, Assistant Archivist Yao Qianying, of the Records Management Department. This photo was taken in 2017 when the National Archives was vacating its premises at 1 Canning Rise for major renovations. Courtesy of Mrs Kwek-Chew Kim Gek.

Mrs Kwek-Chew Kim Gek (left) with colleague, Assistant Archivist Yao Qianying, of the Records Management Department. This photo was taken in 2017 when the National Archives was vacating its premises at 1 Canning Rise for major renovations. Courtesy of Mrs Kwek-Chew Kim Gek.

On joining the National Archives and Records Centre (NARC) – as the NAS was known back then – in 1974:

I’ve always wanted to be a teacher or librarian, but when I saw an ad for an archives and records position, I decided to apply. I hadn’t the faintest idea what an archivist did as archival work was new at the time in Singapore, but the job description attracted me as I’ve always had a keen interest in history. Many people didn’t even know how to pronounce the word “archives” back then and we had to correct them while trying to keep a straight face (“are-cheeves” was one of the several permutations!).

On the set-up of the NARC in the 1970s:

The archives was still in its infancy in those days. We had fewer than 10 staff members, and resources and funding were very tight. My boss Mrs Lily Tan, who would become the first director of the archives, used to describe our operations as a “man, a woman and a dog set-up”!

On the training of young archivists in the 1970s:

There were no formal courses to attend and I had no experienced colleagues to learn from. Training was on the job. We had to familiarise ourselves with the standard textbooks on archives and records by the two gurus of archives: T.R. Schellenberg and Hilary Jenkinson.

Mrs Kwek-Chew Kim Gek (extreme right) with colleagues at an office function to celebrate the National Archives’ 25th anniversary in 1993. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Mrs Kwek-Chew Kim Gek (extreme right) with colleagues at an office function to celebrate the National Archives’ 25th anniversary in 1993. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

In 1983, after almost 10 years on the job, I was sent on a three-month attachment with the State Archives of New South Wales, Australia, and in 1991, on a two-month stint in Ottawa and Toronto in Canada. These attachments combined theory and practice, and enabled me to meet archivists from all over the world. This network of contacts would prove extremely valuable in time to come when I had to seek advice from experienced people on archival best practices.

On collecting private records from religious organisations:

One of my first tasks was to microfilm archival records of churches and Hindu temples. In those days, the churches were a little suspicious of our intent and unwilling to release their records to us. So, together with a photographic assistant from the National Library, we carted along a portable microfilm camera and carried out microfilming on site at the church premises. This was not ideal because we couldn’t control the ambient lighting to obtain the best results. Still, we made do… Going to a Hindu temple to collect records was a bit of a culture shock for me. Once, I was greeted by a Hindu priest with a chalk-marked bare torso and I didn’t know where to avert my eyes!

On the value of NAS for Singaporeans:

First and foremost, to meet the needs of the man in the street. Private records are important documents that any ordinary citizen might seek access to. For example, there are people who ask for copies of their school attendance records to show as proof when registering their children at the same school. We’ve also had people requesting for their marriage certificates in order to settle inheritance and estate matters.

Second, archival records help us to understand ourselves as Singaporeans. The Maria Hertogh riots of 1950 and the racial riots of 1964, for example, teach us that race and religion are sensitive issues in Singapore and things that we should never take for granted. Reading primary records and listening to oral history accounts can give us new perspectives on historical events that have already been extensively documented.

Finally, by providing public servants with access to past official records, they can learn which government programmes and initiatives were successful and which ones failed. This can be a useful exercise when framing and implementing new public policies.

Interview was conducted by Mark Wong, Senior Oral History Specialist at the Oral History Centre, National Archives of Singapore.

Fiona Tan is an Archivist with the Outreach Department, national Archives of Singapore where she conducts research to promote a greater awareness of its collections.

Fiona Tan is an Archivist with the Outreach Department, national Archives of Singapore where she conducts research to promote a greater awareness of its collections.

NOTES

-

Colony’s history to be preserved: Government will appoint an archivist. (1938, April 17). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Raffles Museum and Library. (1940). Annual report for the Raffles Museum and Library for the year 1939 (p. 7). Singapore: GPO. (Microfilm no.: NL5723). ↩

-

Old colonial documents comprehensively indexed. (1940, June 14). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tan, S.C. (1945, October 31). Report entitled ‘The Archives at Raffles Museum’, forwarded by Lt-Col Archey to Headquarters of the British Military Administration [File reference MSA1141/259], Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore. ↩

-

Corner, E.J.H. (1981). The marquis: A tale of Syonan-to (pp. 60, 137). Singapore: Heinemann Asia. (Call no.: RSING 959.57023 COR-[HIS]) ↩

-

While Michael Tweedie initially wanted to send Tan Soo Chye to London to study archives administration at the University College London, the realities of budgetary considerations ultimately meant Tan’s professional development would have to be pursued locally. See correspondence between Tweedie and the Colonial Secretary: Tweedie, M. W. F. Tweedie. (1948, May 31). Letter to Colonial Secretary [File Reference: MSA1155/399]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore. ↩

-

University arts exam results. (1951, July 7). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tan Soo Chye’s career progression can be tracked through mentions in the following: Raffles Museum and Library. (1954). Annual report for the Raffles Museum and Library for the year 1953 (p. 1). Singapore: GPO. (Microfilm no.: NL5723); Mr. Tan takes top customs post. (1960, November 4). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.; National Archives and Records Centre. (1976). Annual report of the National Archives and Records Centre 1975 (p. 4). Singapore: GPO. (Microfilm no.: NL26798); National Archives and Records Centre. (1977). Annual report of the National Archives and Records Centre 1976 (p. 5). Singapore: GPO. (Microfilm no.: 26799). ↩

-

For example, see Lim, J. (Interviewer). (2000, May 19). Oral history interview with Ng Cheng Onn [Recording no. 002274/17/6]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Lumps are being eaten out of our history. (1953, June 14). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Parkinson, C.N. (1956, April 19). Digging up Malaya’s past will take ten years to complete. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tregonning, K.G. (1956, April 23). National Archives call. The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

For instance, see Tregonning, K.G. (1961, October). An archival system for Singapore. Majallah Perpustakaan Singapura, 1 (2), 53–54. (Microfilm no.: NL27804) ↩

-

The Toyo Bunko, or “Oriental Library”, is the largest Asian-studies library in Japan. ↩

-

Tregonning mentions this in his interview. See Lim, J. (Interviewer). (2003, July 31). Oral history interview with K.G. Tregonning [Transcript of recording no. 002783/6/5, pp. 55-56]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Verhoeven, F. R. J. (1967). Singapore: The national archives and records management, 15 April–14 August 1967. Paris: UNESCO (Call no.: RCLOS 025.171095957 VER) ↩

-

Details of the archives’ expansion can be traced through the National Archives and Records Centre’s annual reports, in particular the 1969, 1970, 1973, 1976 and 1984 issues. (Microfilm nos.: NL26798, NL26799 and NL26699). ↩

-

Annual report of National Archives and Records Centre 1970 – 1971, p. 8. The lack of a conservation unit was reported as an urgent priority action item on p. 11 of Verhoeven’s report. ↩

-

Anuar, H. (1970, July). Current research resources on Southeast Asia in the National Library and the National Archives and Records Centre, and an account of the bibliographical project in progress. Southeast Asian Archives, 3, 30–33. (Microfilm no.: NL27911). ↩

-

For details of Hedwig Anuar’s appointments, see Southeast Asia Regional Branch of the International Council on Archives. (n.d.). Executive Board. Retrieved from SARBICA website. ↩

-

In fact, Verhoeven notes on p. 18 of his report that Lily Tan was selected out of seven candidates to be sent overseas to study archives administration, making her the first employee of the National Archives and Records Centre even before it was officially established. The Colombo Plan is an intergovernmental regional organisation that supports economic and social development of member countries in the Asia-Pacific region. It funds scholarships for developing countries to train their local human resources. ↩

-

Kwa, C.G. (2005). Desultory reflections on the Oral History Centre (p. 4). In D. Chew (Ed.), Reflections and interpretations: Oral History Centre: 25th anniversary publication. Singapore: Oral History Centre. (Call no.: RSING 907.2 REF) ↩

-

The history of the organisation’s restructuring can be traced through the National Archives and Records Centre’s annual reports, in particular the 1979, 1980 and 1985 issues. (Microfilm nos.: NL26799 and NL26699) ↩

-

Since the inception of the National Archives and Records Centre in 1968, microfilming had been the archives’ principal means of preserving paper records, and the work was handled by the National Library’s Microfilm Unit. However, the volume of records later increased significantly beyond the National Library’s capacity. ↩

-

National Heritage Board. (1997). Annual report of the National Heritage Board 1996/1997 (p. 23). Singapore: GPO. (Microfilm no.: NL26739) ↩

-

For details of these digital initiatives, see Annual report of the National Heritage Board 1996/1997 and 150,000 historical images online. (1998, April 29). The Straits Times, p. 31. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

For more information on the establishment of the Audiovisual Archives Department, see National Heritage Board. (1996). Annual report of the National Heritage Board 1995/1996 (p. 48). Singapore: GPO. (Microfilm no.: NL26739) ↩

-

Close to 30 books, many of which began as exhibitions, were published, including collection-specific features such as Singapore Retrospect through Postcards, 1900–1930 (1982) (Call no.: RSING 769.4995957 SIN); place and community histories such as The Development of Nee Soon Community (1987) (Call no.: RSING Chinese 959.57 DEV-[HIS]); useful research indexes such as Index to Papers and Reports Laid before the Legislative Council of the Straits Settlements (1867–1955) (1992) (Call no.: RSING 016.328595704 CHN-[LIB]) ↩

-

Dramatists get help from the archives. (1994, August 28). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

For details of the various positions, see Southeast Asia Regional Branch of the International Council on Archives. (n.d.). Executive Board. Retrieved from SARBICA website. ↩

-

For details, see National Archives. (1992). Annual report of the National Archives 1991 (p. 2). Singapore: GPO. (Microfilm no.: NL26724) ↩

-

For details, see National Heritage Board. (2001). Annual report of the National Heritage Board 2000/2001 (p. 21). Singapore: GPO. (Microfilm no.: NL27503) ↩

-

For details, see National Heritage Board. (1999). Annual report of the National Heritage Board 1998/1999 (pp. 28–29, 38). Singapore: GPO. (Microfilm no.: NL24110) ↩

-

For details of the new amenities and services of the Archives and Oral History Department in the Old Hill Street Police Station building, see Ministry of Culture. (1984, May 26). Speech by S Dhanabalan, Minister for Foreign Affairs and Minister for Culture, at the official opening of the Archives and Oral History Department at Hill Street Building. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

For details of the new building, see National Heritage Board. (1998). Annual report of the National Heritage Board 1997/1998 (p. 22). Singapore: GPO. (Microfilm no.: NL26741) ↩