The Way We Were: The MITA Collection 1949–1969

Photographs can capture subtext that is sometimes more evocative than the intended subject, as Gretchen Liu discovered when she explored the early work of the Photo Unit.

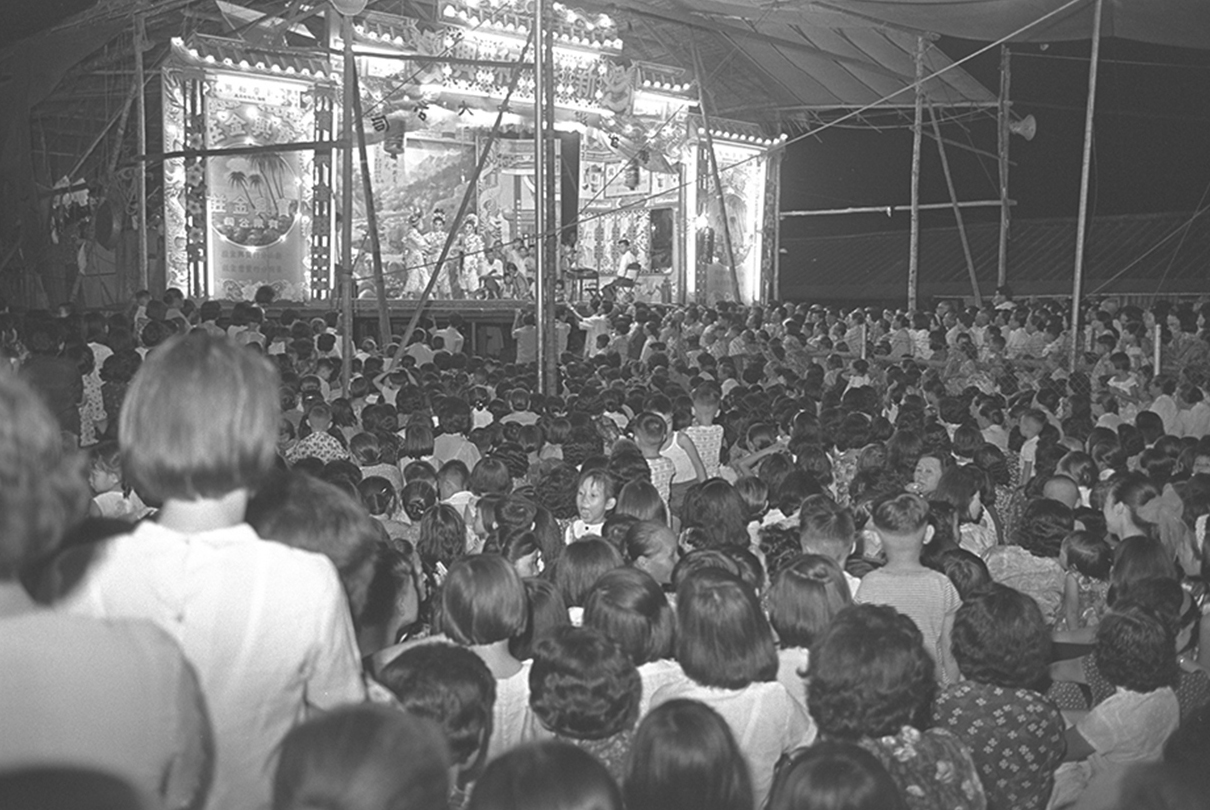

A Chinese opera staged in Kampong Glam, 1966. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A Chinese opera staged in Kampong Glam, 1966. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.The National Archives of Singapore (NAS) houses an astonishing five million prints, slides and negatives that vividly tell the story of modern Singapore. With the Archives Online portal providing access to over a million of these images, anyone can easily explore Singapore’s visual heritage with an internet connection and a few clicks.

While the collection includes photographs from private sources, a far greater number come from government departments. Of these, the vast majority are transfers from the Photo Unit, a small government department staffed by professional photographers and with its own in-house dark room for processing negatives. The history of the Photo Unit can be traced back with certainty to 1949. The photos are identified by the source line “Ministry of Information and the Arts”1 (MITA).

The Photo Unit captured events, milestones and scenes of Singapore through the twilight years of the colonial era. With the attainment of self-government in 1959, the unit acquired a renewed sense of purpose: in the days before television, photographs were a vital means of communicating new ideas, goals and achievements. Given the rapid pace of change in Singapore’s physical, social and economic landscape, these black-and-white compositions from the 1950s and 60s offer not only invaluable documentation but also captivating, sometimes surprising, and occasionally nostalgic, glimpses of the way we were.

Beginnings

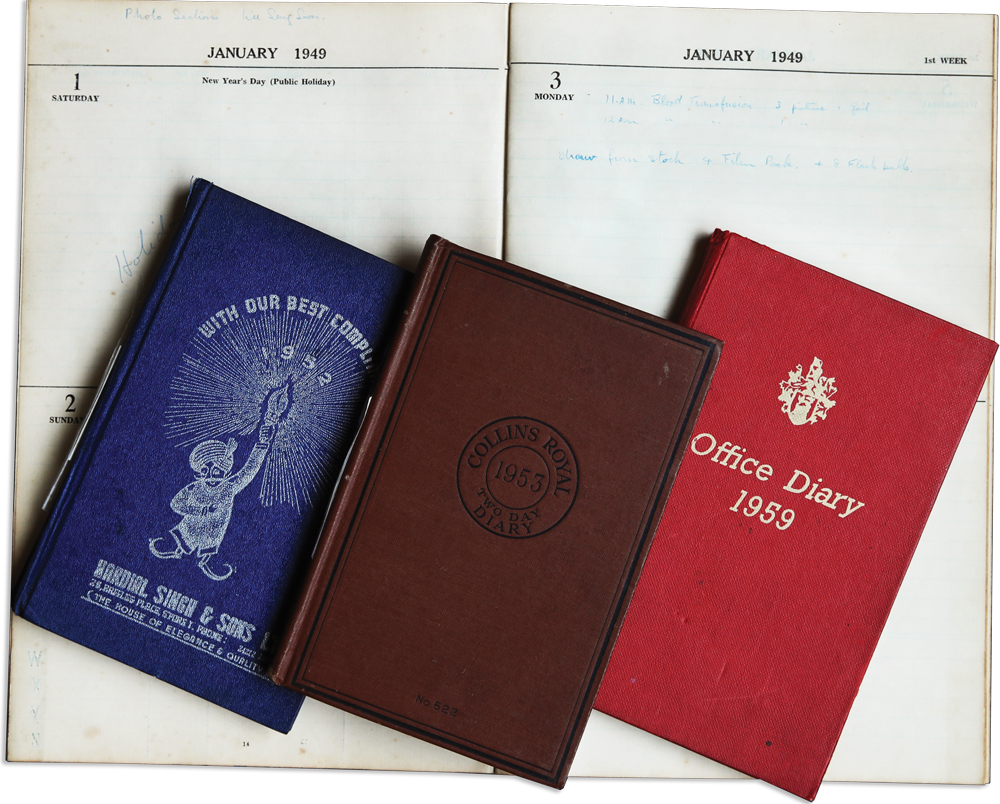

The Photo Unit’s first assignment book is a dark blue 1949 government-issued “Office Diary” – which is with the NAS. The first entry was penned on 3 January at 11 am as “Blood Transfusion. Fail” (the session was repeated at 12 noon, presumably a success). The use of four film packs and eight flash bulbs was logged. The subject matter is a poignant reminder of the seriousness of post-war health issues, with diseases caused by malnutrition and rampant poverty. Tuberculosis, a manifestation of slum conditions aggravated by the war, was all too common then.

Office diaries recording assignments taken by the Photo Unit – including the page with the very first entry on 3 January 1949. Courtesy of Ministry of Communications and Information.

Office diaries recording assignments taken by the Photo Unit – including the page with the very first entry on 3 January 1949. Courtesy of Ministry of Communications and Information.The state of the health of the population was just one of many troubling issues. With the end of British military rule – that followed the surrender of the Japanese – on 31 March 1946, the Straits Settlements was dissolved and Singapore became a Crown Colony, though a poor and shabby one. The population was nearing the one million mark, and there was a larger proportion of women, children and the elderly. Post-war economic recovery was slow and the future uncertain. Threats both external and internal faced the colonial government – armed insurgency by communist groups in Malaya on the one hand, and the activities of left-wing groups operating in Singapore on the other. Harsh measures were imposed. At the same time, the inevitability of eventual independence from the British was already manifestly apparent, even as the journey to that goal was utterly unclear.

A first small step was taken on 1 April 1948 when the colonial structure was amended to include a Legislative Council comprising several elected local members. Public opinion now mattered, and photography was perceived as having a useful role to play.

“The creation of a public relations branch was a tacit recognition of the large and legitimate part which public opinion must play in shaping the future of the Colony,” advised the 1948 Singapore annual report. The report acknowledged the need for the government “to keep the public informed of its policies and of the administrative details and functions arising out of the carrying out of those policies at a time of ever-growing public interest in public affairs and a readiness to assume responsibility for them”.2 The authorities were also cognisant of the need to instill allegiance by spinning a positive light on its affairs to promote “a common and active loyalty to the Colony, its security and its welfare”.3

Fishermen with the day’s catch, 1951. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

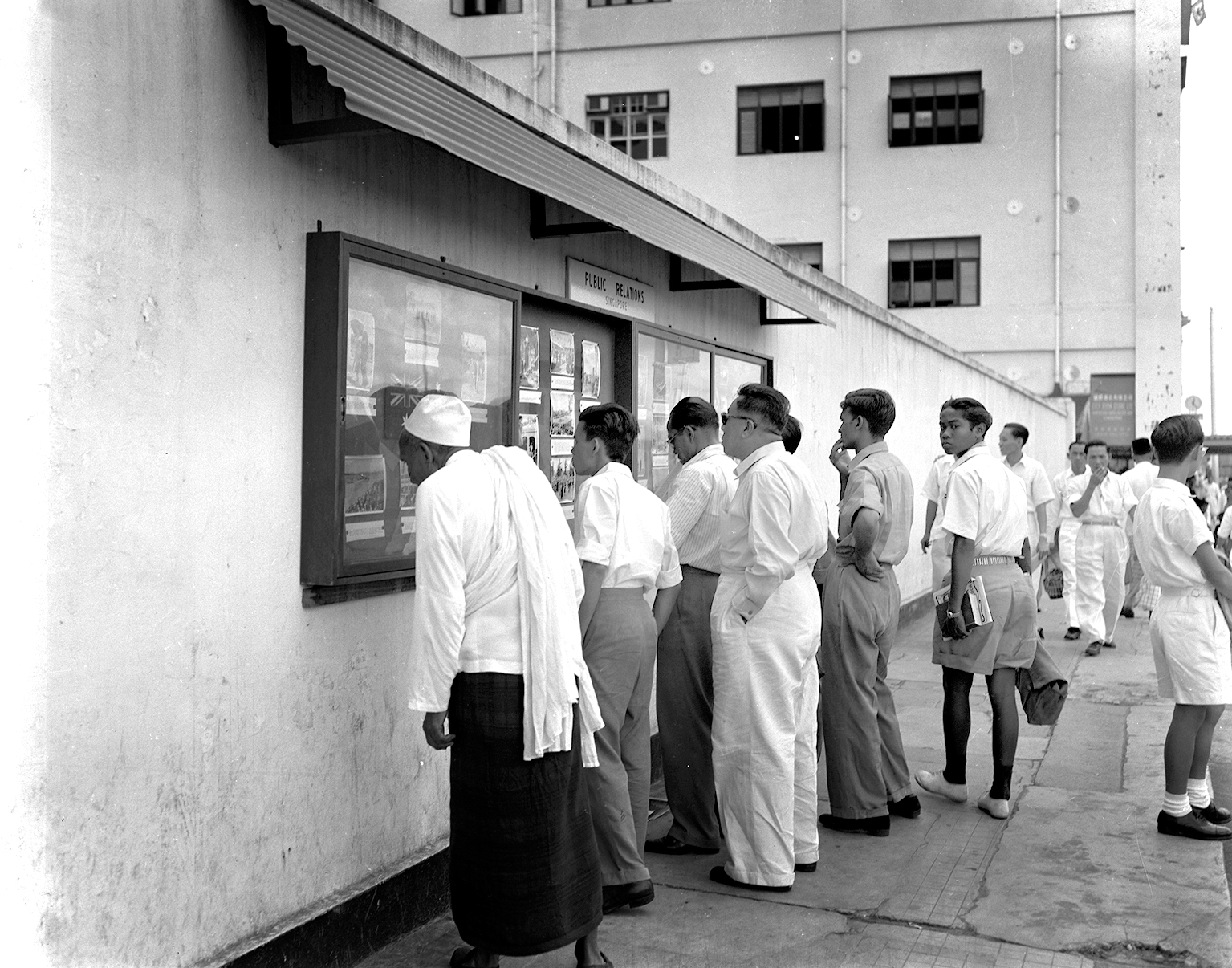

Fishermen with the day’s catch, 1951. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.Browsing through MITA’s online photograph collection from the 1950s is like taking a slow journey through a very, very different Singapore. There are the expected official events and VIPs but also plenty of images that offer a time capsule of the island and everyday life, and youthful versions of familiar faces. Many of these images were first displayed in official “photo boxes” erected around the island. Back then, photo boxes – literally glass cases displaying important notices and photographs – were used by the government as a means to disseminate information to the public. In 1953, there were 53 such photo boxes and, by 1956, the number had increased to 93.4

Photo boxes containing images and notices were used to disseminate information to the public. This photo was taken at Collyer Quay, 1954. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Photo boxes containing images and notices were used to disseminate information to the public. This photo was taken at Collyer Quay, 1954. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.The 1955 general election was the first time a majority of the seats in the Legislative Assembly were elected rather than appointed by the colonial authorities. After the election, the Public Relations Office was renamed the Department of Information Services on 1 January 1957, and relocated to the newly created Chief Minister’s Office. Photographs became increasingly important to government publications and publicity campaigns. Two photographers were on staff to “keep a record of public functions and of departmental activities and to print material for overseas distribution and for use in the publications of the Department or other government publications”. A generous 7,625 negatives were exposed during the year.5

Two years later, in the 1959 general election, Singapore attained full internal self-government when the People’s Action Party (PAP) won the majority of the seats in the Legislative Assembly. The new leaders were in a hurry to engage the hearts, minds and imaginations of people living in a complex multiracial society with divided loyalties and the legacy of colonial rule. Housing, education, the economy and jobs were all hot topics. New policies and programmes needed to be conceptualised and conveyed to the public.

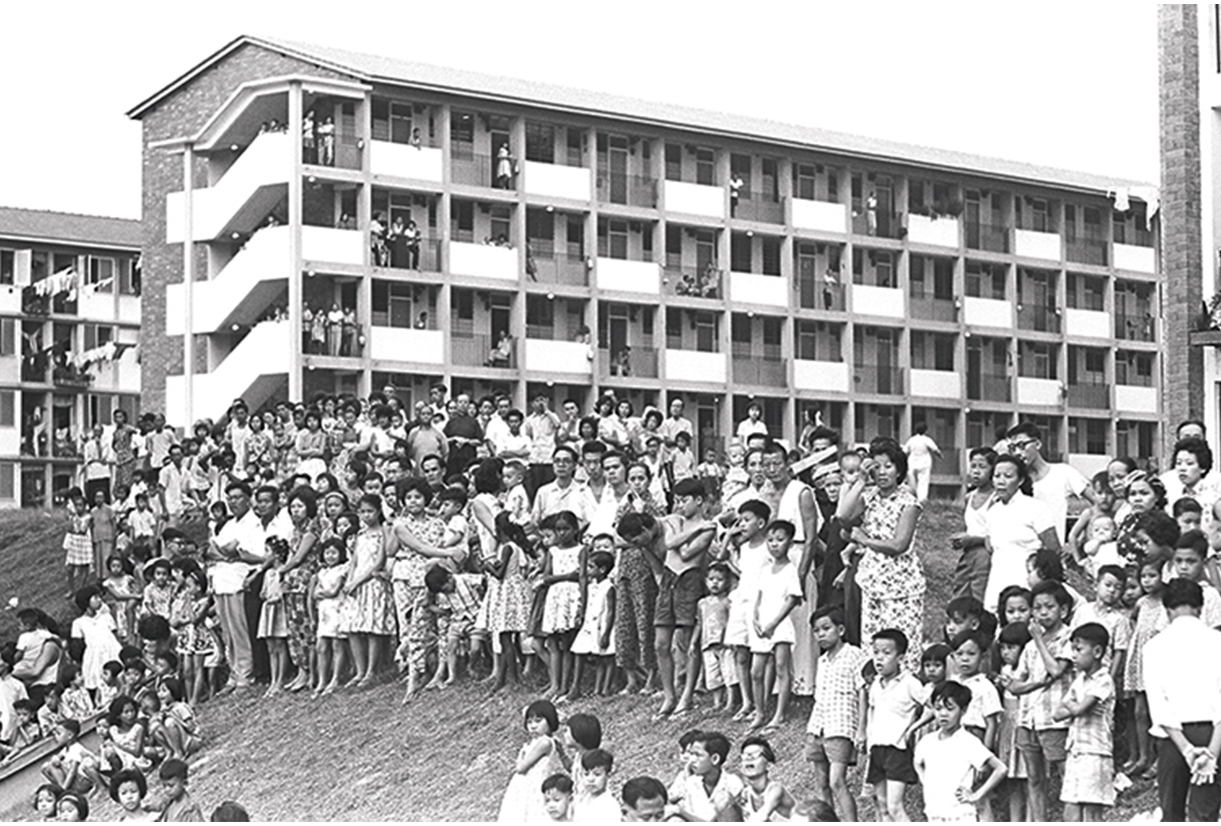

Flat dwellers waiting for then Prime Minster Lee Kuan Yew during his tour of Tiong Bahru, Delta and Havelock housing estates in 1963. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Flat dwellers waiting for then Prime Minster Lee Kuan Yew during his tour of Tiong Bahru, Delta and Havelock housing estates in 1963. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.The Photo Unit Steps Up

The task fell to the new Ministry of Culture (MOC), whose goal was to “channel popular thinking and feeling along national lines and to re-organise the Information Services and the administration of mass media for the dissemination of information”.6 In effect, the MOC served as the government’s public relations arm, educating newly minted citizens about government policies and rallying people around a Malayan national identity in anticipation of merger with Malaysia.

Sinnathamby Rajaratnam (1915–2006), or S. Rajaratnam as he was better known, a former journalist and a founding member of the PAP, served as the first minister for culture for six years, from 1959 until 1965. In that role, he was given the responsibility of formulating policies to create a sense of shared identity, a common Malayan culture and to keep the people informed. He soon earned a reputation as the government’s chief communicator.

Rajaratnam grasped that government ideals and policies, no matter how brilliant, needed to be communicated effectively or they would fail: not abstract slogans, but something more concrete was needed. Photographs were the ideal medium. Perhaps more than any of his fellow cabinet members, Rajaratnam understood the power of pictures. Apart from being a gifted writer, he was also a keen amateur photographer. The hobby was acquired during his student days in London, from 1935 to 1947. Surviving images from this time attest to his aptitude as he framed everyday scenes from unusual perspectives or with a distinctly modern flair.7

Not surprisingly, the Photo Unit, now absorbed into the new ministry, became engaged in a flurry of activity. In 1959, over 9,000 negatives were exposed, covering major news events and keeping a record of the government’s activities. Multiple copies of selected negatives were printed, a staggering 71,200, many of which were displayed in the ubiquitous photo boxes scattered around the island. Others were supplied to the press, local and overseas organisations as well as to the general public on request.8

Photographs also provided the raw material for other media, including Photo News, a series of large-format information posters with bright background colours and captions and explanatory notes in the four official languages. Over the next nine years, Photo News graphically conveyed the story of changing Singapore – the expansion of industry and housing estates, the launch of national service, cultural events and infrastructure projects. Ministers and members of parliament were featured opening schools, factories and community centres. Some issues were devoted entirely to foreign affairs, sharing the latest news on the prime minister’s visits overseas or foreign leadersʼ visits to Singapore.

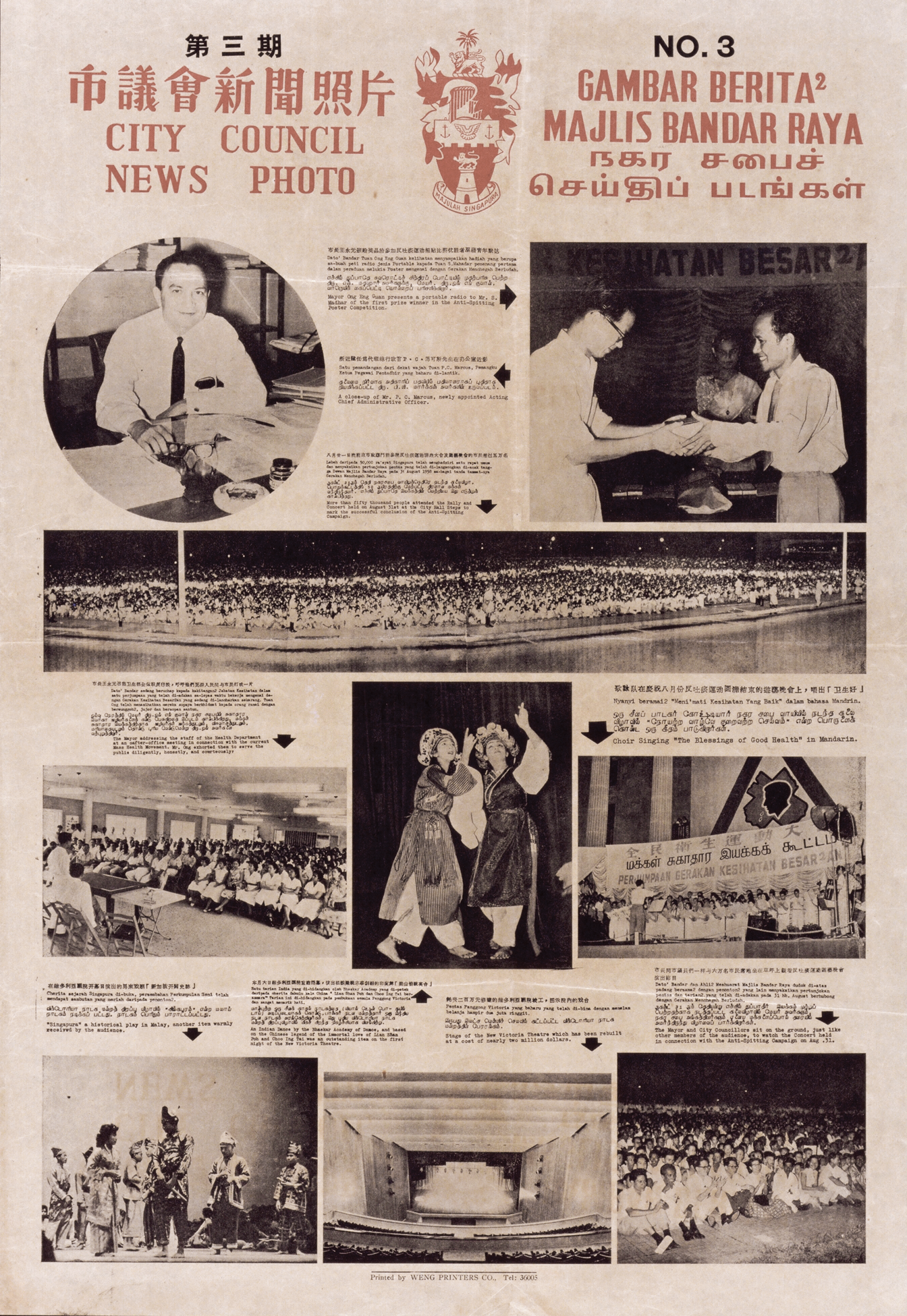

City Council News Photo No. 3 (text in English, Chinese, Malay and Tamil). Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

City Council News Photo No. 3 (text in English, Chinese, Malay and Tamil). Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.The 1960s was a decade of turbulence and transformation, and the Photo Unit was kept busier than ever. The work of the photographers continued to be reproduced in booklets, posters and various promotional materials and publications circulated by the ministry’s Publicity Division. Even with the advent of television, photography continued to play an important role. The first television broadcast took place on 15 February 1963 and regular broadcasting started a few weeks later. But few households owned television sets due to their high cost, and broadcasting was limited to only a few hours in the evening.

Data published in the Singapore annual reports record the prolific output of the Photo Unit. In 1960, some 8,835 film negatives were exposed and 71,864 photographs printed.9 By 1965, negatives were no longer counted but printed photographs were – some 209,800 that year. These serviced “53 photo boxes in markets and display boards in Government offices and 1,388 photo display boards in bus shelters and coffee shops”.10 In 1966, the unit printed 241,500 photographs. There were “some 53 photo boxes in markets as well as 53 photo boxes and display boards in Government Offices and 1,383 photo display boards at bus shelters and coffee shops which carry the Weekly Photo News posters published by the Division”.11

Keeping Up with the Times

By the end of the 1960s, however, there was a distinctive shift. The use of photography for nation-building purposes was superseded not only by the widespread ownership of television sets, but also by the changing requirements of an increasingly sophisticated society. Photo News as a medium of communication was deemed outdated and ceased publication in 1968. The once omnipresent photo boxes were gradually dismantled. The very last photo box to be removed was on the High Street side of the Supreme Court building, sometime at the end of the 1980s. At the same time, a stronger awareness of the need to preserve the country’s history emerged. An important milestone was the establishment of the National Archives and Records Centre in 1968,12 which was tasked with the custody and preservation of public records, including photographs.

Workers at a pineapple canning factory, 1952. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Workers at a pineapple canning factory, 1952. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.The Photo Unit has, however, continued in its work to photograph Singapore. Today, the unit is part of the Ministry of Communications and Information, and housed at the Old Hill Street Police Station building. Veteran photographer Goh Lik Huat, who joined the Photo Unit in October 1977, recalls that six or seven full-time photographers have manned the unit at any one time over the years. Over time, the nature of the assignments undertaken has evolved. Originally, the unit covered a wide range of activities, but the focus has narrowed down to the office of the president, prime minister and some key members in the Prime Minister’s Office.

Cameras are government-issued – from Rolleiflex film cameras in the 1950s to Leica cameras from 1965, and Canon digital cameras today. Black-and-white film continued to be used until the 1990s, but overlapped with and was eventually replaced by the use of colour film. The switch to digital cameras took place in the early 2000s. Each year, the unit organises its collection of photographs for transfer to the NAS where they are catalogued and made accessible to the public. In the early days, negatives were sent together with a printed contact sheet for easy reference. Today, the files are saved in compact discs. Technology has changed, but there is one endearing example of continuity: daily assignments are still manually recorded in an office diary.

Capturing the Bigger Scene

A photograph captures a moment in time and can be rich in unintended documentation – background shophouses, littered streets, barefoot children. In striving for the perfect shot, many of the less-than-perfect photographs have a gritty spontaneity that seem to fit the subject and the times. As William Henry Fox Talbot (1800–77), the English scientist and inventor who was one of the pioneers of photography, observed in The Pencil of Nature, the first photographically illustrated book published commercially: “It frequently happens, moreover – and this is one of the charms of photography – that the operator himself discovers on examination, perhaps long afterwards, that he had depicted many things he had no notion of at the time.”13

That the photographs from this era were taken with the idea of swaying public opinion or rallying citizens is in itself of historical interest. While only a few photographs from the collection can accompany this essay, the full sweep of history can be enjoyed by exploring the images on Archives Online. Alongside historic moments and iconic personalities, the MITA photograph collection offers insights into ordinary people and everyday affairs. Preserved, documented in place and time, they can be exhibited, reproduced, studied, interpreted, re-evaluated and, above all, enjoyed.

Gretchen Liu is a writer and former book editor with an interest in visual heritage. She is the author of Singapore: A Pictorial History 1819–2000. Her work on other Singapore book projects has often included – most enjoyably – research in the National Archives.

NOTES

-

The predecessor of the Ministry of Information and the Arts (MITA) was the Ministry of Culture, which was formed in 1959. In 2001, MITA was renamed the Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts, but retained the acronym MITA. In 2004, the acronym MITA was changed to MICA. In 2012, MICA was renamed the Ministry of Communications and Information. ↩

-

Singapore. Ministry of Culture. (1949). Colony of Singapore annual report 1948 (p. 14). Singapore: Information Division, Ministry of Culture. Available via PublicationSG. ↩

-

Colony of Singapore annual report 1949, p. 2. ↩

-

Colony of Singapore annual report 1953, p. 180; Colony of Singapore annual report 1956, p. 233. ↩

-

Colony of Singapore annual report 1957, p. 257. ↩

-

State of Singapore annual report 1959, p. 189. ↩

-

For more on Rajaratnam and his interest in photography see Ng, I. (2010). The Singapore lion: A biography of S. Rajaratnam. Singapore : Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSING 327.59570092 NG) and Rajaratnam, S. (2011). Private passion: The photographs of pioneer politician and diplomat S Rajaratnam. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSING 779.092 RAJ) ↩

-

State of Singapore annual report 1959. See Chapter VIII, “Cultural Affairs, Information and Publicity”. ↩

-

Singapore annual report 1960, p 206. ↩

-

Singapore yearbook 1965, p. 207. ↩

-

Singapore yearbook 1966, p. 228. ↩

-

The National Archives and Records Centre, the predecessor of the National Archives of Singapore, marks the beginning of the first independent archives institution in Singapore. Prior to this, the archives office was part of the former Raffles Museum and Library. ↩

-

The Pencil of Nature was published in instalments between 1844 and 1846. The quote appears in Newhall, B. (1982). The history of photography: From 1839 to the present day (p. 246). New York: The Museum of Modern Art. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩