US Ex Ex: An Expedition for the Ages

The Wilkes Expedition – as it is popularly known – vastly expanded the borders of scientific learning. Vidya Schalk explains how this historic American naval mission between 1838 and 1842 is linked to Singapore.

In early 1842, almost 500 naval officers, sailors and scientists from the United States visited Singapore on their way home after an epic four-year voyage of discovery. They were members of the United States Exploring Expedition, part of the last All Sail Naval Squadron to circumnavigate the globe and the first-ever scientific mission mounted by the fairly young nation (the country had achieved independence in 1776).

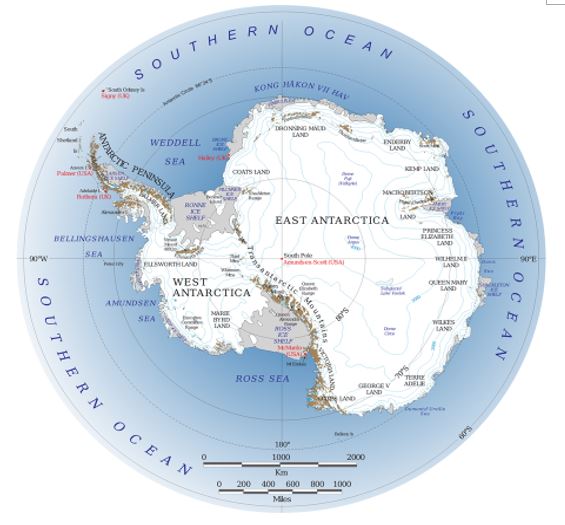

Few people have heard of the Wilkes Expedition, its more commonly used name, and fewer still about the United States Exploring Expedition – or simply the U.S. Ex. Ex. Although the expedition became mired in controversy, it nonetheless left behind an important legacy in its meticulous documentation of the earth’s biodiversity. Among its contributions are the first-ever systematic mapping of the coastline of the US Pacific Northwest, the charting of some 1,500 miles (2,414 km) of the frozen Antarctic coast, and the first concrete proof that Antarctica is a continent.

The Mission

The Wilkes Expedition was primarily a mission of exploration. It aimed to extend the borders of learning, and came at a time when Britain, France and other European nations were busy expanding their territories through colonisation. The mission parameters were two-fold – navigational and scientific – as directed by the US Congress:

“To explore and survey the Southern Ocean, having in view the important interest of our commerce embarked in the whale fisheries, as well as to determine the existence of all doubtful islands and shoals; and to discover and accurately fix the position of those which lie in or near the track pursued by our merchant vessels in that quarter… Although the primary object of the expedition is the promotion of… commerce and navigation, yet all occasions will be taken, not incompatible with the great purpose of the undertaking, to extend the bounds of science, and to promote the acquisition of knowledge…”1

Genesis of the Expedition

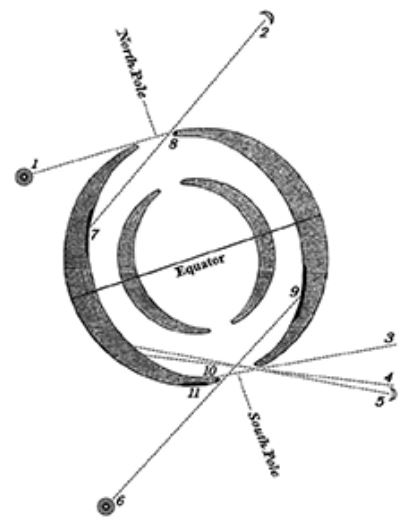

In 1818, an American eccentric named John C. Symmes put forward the “Holes in the Poles” theory. He declared the earth as hollow, with a habitable interior only accessible through openings at the North and South poles that were large enough to accommodate sailing ships. This was picked up by an enterprising newspaper editor from Ohio, Jeremiah Reynolds, who called for further research to establish the veracity of the so-called “polar holes”, eventually advocating a national maritime expedition to explore the mysteries of the South Pole. By 1828, Reynolds had managed to pique the interest of US Naval Secretary Samuel Southard and President John Quincy Adams.

Support also came from whalers and sealers who needed accurate charts of islands and navigational hazards in the Pacific Ocean. Whaling had become a booming business – whale oil was as significant then as crude oil is today – and the US was then the global industry leader. With whales hunted to near extinction in the Atlantic Ocean, the Pacific Ocean was the next fertile ground and the ability to navigate safely in these waters would be crucial to its success.

The process of getting the expedition off the ground, however, dragged on for almost a decade as the government’s priorities shifted due to political changes and financial pressures. Also, the public was suspicious of any scientific research, considering it the idle pastime of bored aristocrats. The expedition soon earned the unfortunate moniker the “Deplorable Expedition”.

In the midst of this, the financial crisis known as the Panic of 1837 struck the nation and thrust the American economy into chaos. Nonetheless, in 1838, against all odds, as directed by Secretary of War Joel Poinsett (who was also an amateur botanist), the U.S. Ex. Ex. was put back on the agenda and Lt. Charles Wilkes was asked to take full command of the mission.

A full-blown controversy erupted when this was announced. Wilkes (see text box below) was one of 40 lieutenants on the navy list, along with 38 others who had chalked up more sea service than him. Such a command conferred upon a junior officer was unprecedented in the naval service and caused an uproar. Letters of protest poured in and heated debates ensued in Congress, but in the end the appointment went through.

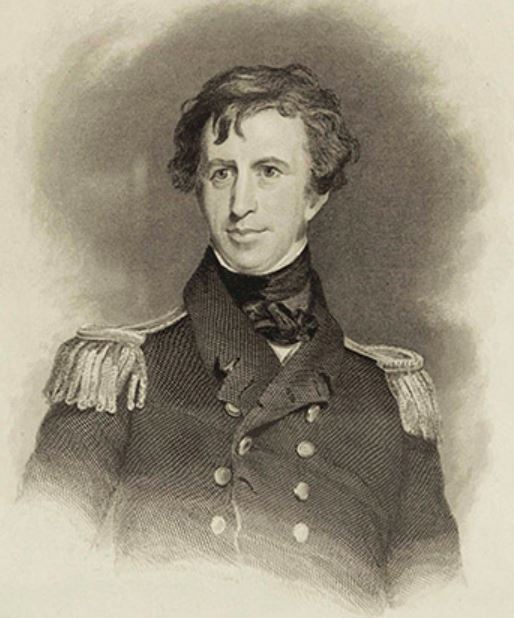

A MILITARY MAN AND A SCIENTIST

Lt. Charles Wilkes was 40 years old when he was given command of the U.S. Ex. Ex. in 1838. Wilkes was a military man and a scientist – a very exacting combination. He was also a proud man who firmly believed that no important accomplishment could be achieved without discipline. He demanded much of himself and those around him.

In addition to being self-opinionated and stubborn, Wilkes possessed a fiery temper and, as a result, became embroiled in frequent altercations with his superiors throughout his naval career. Incidentally, Wilkes is believed to be the inspiration for the character Captain Ahab in Herman Melville’s 1851 classic, Moby Dick.2

But the truth was, in spite of his relatively junior rank, no officer in the navy was more suitable than Wilkes to lead the scientific mission. He had trained under two of the leading scientists in their fields – James Renwick and Ferdinand Hassler – under whose tutelage he became proficient in astronomy, magnetism, geodesy and nautical surveying.

True to his character, Wilkes accepted the appointment to lead the squadron as no more than his due and was granted a great deal of autonomy by Secretary of War Joel Poinsett to make plans and lead the expedition. The Ex. Ex. had many daunting objectives to fulfill – and Lt. Charles Wilkes was deemed the best person for the job.

The A-Team

Wilkes personally selected the vessels, crew and scientists for the expedition. He also decided that all duties pertaining to astronomy, surveying, hydrography, geography, geodesy, magnetism, meteorology and physics would be the preserve of the naval officers. Any work relating to zoology, geology and mineralogy, botany and conchology was to be filled by the naval medical corps, failing which civilians could be appointed.

All personnel and crew members of the expedition came under the control and direction of Wilkes. Disappointed that there was no “respectable naturalist”3 in the medical corps, he fell back on the best civilian talents the country could offer. The “Scientifics”,4 as they were called, were a group of brilliant scientists and naturalists, almost all of whom went on to redefine the scientific fields of botany, zoology and geology as well as then emerging fields like volcanology and anthropology. Two artists were also part of the crew: they sketched and used the camera lucida – an optical device used to aid drawing – to capture portraits of people and to maintain a visual record of the voyage.

Also assembled onboard were taxidermists, equipment makers, carpenters, sailmakers and surgeons, in addition to naval officers (many of whom later became high-ranking servicemen), marines and other sailors. It was not glory or wealth but the thirst for knowledge that inspired many of these men to leave their homes and embark on a journey into the unknown.

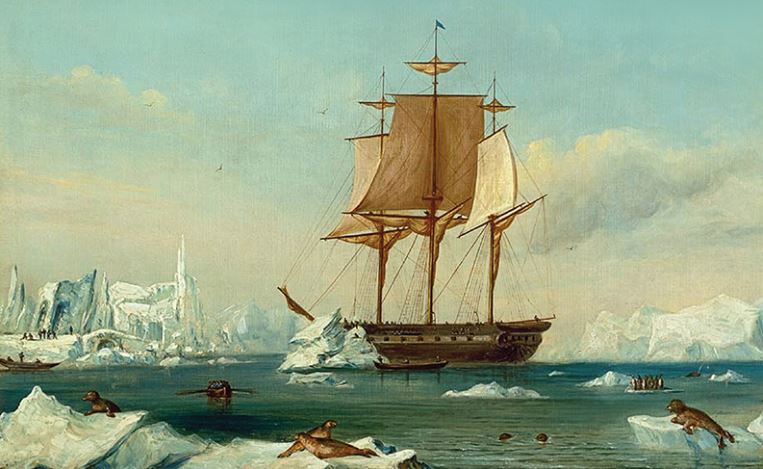

Sailing to the Ends of the Earth

The U.S. Ex. Ex. set sail at 3 pm on 18 August 1838 from New York. From the east coast of the United States, the fleet sailed to Madeira in Portugal, stopping at Porto Praya before heading to Rio de Janeiro in South America and then southwards to Cape Horn at the Tierra de Fuego, where they made their first attempt to reach the Antarctic.

The gales and terrible weather, however, forced the ships to turn back but not without the tragic loss of the USS Sea Gull: its 15 men on board were never seen again. The rest of the fleet sailed to Peru and headed westwards to survey and explore the Tuamotu and Society islands in the South Pacific, before moving on to Tahiti and Samoa, and finally arriving in Sydney, Australia, in November 1839.

The fleet sailed into Sydney harbour in the middle of the night. Delighted to be at a port where English was spoken, the Americans took every opportunity to enjoy the sights. They also noted that rum was used as a medium of exchange; with a population of 24,000 in the city, it seemed there was a tavern for every 100 inhabitants.

From Sydney, the U.S. Ex. Ex. launched a second encounter to the Antarctic on 26 December 1839. Well stocked with 10 months of provisions in case they became trapped in ice, the expedition proceeded south. On 19 January 1840, land was identified at roughly 160 degrees east and 67 degrees south. Wilkes surveyed and mapped nearly 1,500 miles (2,414 km) of the Antarctic coastline – considered a remarkable achievement to this day – providing substantial proof that Antarctica is a continent. In honour of Lt. Charles Wilkes, a million square miles (almost 2,600,000 sq km) of land on East Antarctica is named Wilkes Land.

From the icy waters of the Antarctic, the U.S. Ex. Ex. sailed towards New Zealand and then to the Fiji Islands, where four months were spent on detailed surveying. Altogether, 50 reefs and 154 islands were carefully mapped, but a bloody encounter between the crew members of the expedition and the Fijians would mar this accomplishment. The Fijians had a reputation as cannibals. At first the crew thought these were mere myths but soon realised that the reports were true. As the fleet was preparing to leave Fiji in July 1840, two of its officers, one of them Wilkes’ nephew, were killed by the islanders while bartering for food on Malolo Island. In the subsequent disproportionate reprisal by the Americans, some 60 islanders lost their lives.

Leaving Fiji behind, the expedition headed to Hawaii and from there to survey and chart the American Pacific Northwest in April 1841. From California, the fleet briefly returned to Honolulu and proceeded to Manila in the Philippines. By then, time was running out for the expedition. Wilkes had promised the crew that they would return to the US by the end of May 1842, and the men were eager to get home.

The U.S. Ex. Ex. left Manila in January 1842, making their way home via the Sulu Sea. When Sultan Jamal ul-Kiram I of Sulu sent word that he was interested in establishing closer trading ties with the US, Wilkes signed a peace and trade treaty with the king, which gave protection to US vessels and a shorter passage to Manila and on to Canton (now Guangzhou) in China.

Heading south, on their return journey, the fleet made one last stop in Singapore before returning to the US. The expedition’s documentation of Singapore constitutes one of the first primary accounts of Singapore by Americans.

Singapore Stopover

On 19 February 1842, the USS Vincennes with Wilkes on board arrived in Singapore,5 then part of the Straits Settlements together with Malacca and Penang. Wilkes was warmly received by the US consul Joseph Balestier, his wife Maria Revere – the daughter of the famous American patriot Paul Revere – and son Joseph. The two men had become acquainted some years earlier in Washington prior to Balestier’s arrival in Singapore. In fact, Wilkes had provided Balestier with information on the region, including a copy of the best map he had at the time. Balestier reciprocated Wilkes’ kindness by hosting him in Singapore. Years later, when Wilkes wrote his autobiography, he would make special mention of a huge cabinet presented to him by Mrs Balestier, fashioned out of “woods of this country [Singapore]”.6

Wilkes and his crew were so fascinated with Singapore that he dedicated an entire chapter to the island in his “Narrative” of the expedition.7 Several astute observations were made by Wilkes and the crew during their brief stay here. It is remarkable that several of these observations hold true almost 200 years later.

A Colourful Melting Pot

The crew was amazed by the confluence of races, languages and cultures in Singapore and the peaceful coexistence among the people, the “rarity of quarrels between different races and religions owning to the consideration of the place being neutral ground”. They were also “struck with the order and good behaviour existing among such an incongruous mass of human being[s]… speaking a vast variety of tongues, and some of who would infallibly have been at war with each other elsewhere”.8 Wilkes called Singapore the “Babel of the East”.9

A Thriving Entrepôt

Wilkes estimated there were at least 1,500–2,000 vessels in the port at any one time, with numerous prahu (wooden sailing boats) from neighbouring Riau and Lingga, Celebes, Flores, Timor, Ambon, Sumba and Lubok, and also from resource-rich Borneo. Popular goods imported from Riau and Lingga included pepper, rice, camphor, sago, coffee, nutmeg, oil, tobacco, biche-de-mer (sea cucumber), birds’ nests, tortoise shells, pearls, rattan, ivory, animal hides and sarongs, among other items.10 Boats from Papua and Aru brought birds of paradise flowers, which were found in abundance in the markets of Singapore.

The expedition noted that “every avenue, arcade, or veranda approaching it [the bazaar] is filled with money-changers, and small-ware dealers, eager for selling European goods, Chinese toys, and many other attractive curiosities”.11

Singapore was described as a thriving entrepôt, with arriving goods redistributed to other places, with hardly anything produced here. Vessels that called at the port were not charged duties on imports or exports, and the only questions asked were the contents of the cargo, the value of the goods and the size of the vessel. Such information was then published weekly in the newspaper, “so anyone may inform themselves of the charges he is liable to incur and of the advantages it has over the other ports in the Eastern seas”.12

The era of steam-powered vessels was just starting to take off and Wilkes mentions that “during… [his] stay in Singapore, the subject of steam navigation was much talked of, and many projects appeared to be forming by which the settlement might reap the advantages of that communication, when established between India and China”.13

A Place of Transience

In 1842, the population in Singapore was recorded as 60,000, comprising 45,000 Chinese, 8,000 Malays and 7,000 Indians, with only one-tenth of the whole as female. The people were diverse, with Malays, Chinese, Hindus and Muslims, Jews, Armenians and Europeans, and Parsees, Bugis and Arabs. Wilkes wrote about the transient nature of the population, remarking that “no European looks upon the East as a home, and all those of every nation I met with invariably considered his sojourn temporary”.14 The Chinese, for instance, were likely to return home to China as soon they acquired a skill, even at the risk of being punished for having left their homeland illegally.

Lush Flora and Fauna

Wilkes and his men found the jungle undergrowth in the interior so impenetrable that no Europeans or natives had ever climbed Bukit Timah Hill, the highest point of the island even though it was only 500 ft (152 m) high. Tigers were not indigenous to Singapore, but the big cats had begun to swim across the narrow Johor Strait from the Malay Peninsula in search of food. Even criminals and thieves avoided their usual escape routes in the jungles for fear of tigers.

Records of the crops grown here included nutmeg, coffee, black pepper, cocoa, gambier, gamboge (a kind of resin) and a variety of fruits. Timber was also an important cash crop, and highly prized for shipbuilding. The Americans noted an abundance of fruit in Singapore; they were told “that there are 120 kinds that can be served as a dessert”15 and they especially enjoyed pineapples. They collected many zoological, conchological and botanical specimens, including two species of the Nepenthe (pitcher plants) that were preserved and brought back to the US.

A Vibrant Cultural Scene

The arrival of the U.S. Ex. Ex. in Singapore coincided with the Chinese New Year celebrations. The eve fell on 21 February 1842, and the expedition members were awed by the processions of lanterns, noisy gongs and cymbals. Wilkes described the sight of “an immense illuminated sea-serpent” made of lanterns.16 The Americans were astonished at “the extent and earnestness with which gaming was carried [out] by the Chinese at every shop, bazaar and corner of almost every street with cards or dice… their whole soul seemed to be staked with their money”.17

They also watched a Chinese opera and an Indian theatrical show that was performed by plantation workers on Balestier’s estate. In addition to Chinese New Year, the Americans also encountered Muharram processions.18 Wilkes observed men and boys playing football which he called “hobscob”, although it was most likely sepak takraw, a sport played with a rattan ball and native to the Malay Archipelago. The expedition also witnessed wedding and funeral processions, and even visited Chinese and Hindu cemeteries.

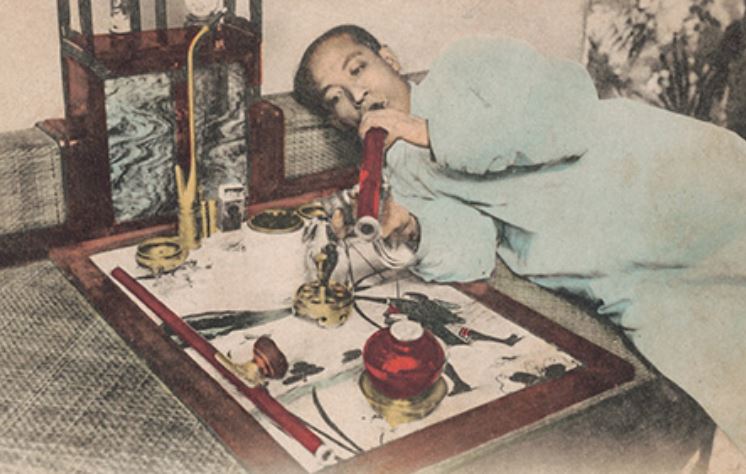

The Scourge of Opium

According to Wilkes’ account, opium smoking in Singapore was one of the most repugnant sights witnessed by expedition members during their time on the island. Opium was easily available and shops were licensed to sell it, which was a huge source of revenue for the government but a great cause of human degeneracy. Many of the vessels that trafficked opium were either owned or operated by merchants. Wilkes noted “how some of those who knew its effects and condemned its use engaged in and defended its trade…”19

One of the crew wrote that opium vendors would set up their “little table in the public street, with his box and scales upon it, and tempting samples of the “dreamy drug… A single glance of these opium dealers will convince you that they are their own best customers… [with] their soiled and disorderly dress, the palsied hand and pale cheek, the sunken eye and vacant stare…”20

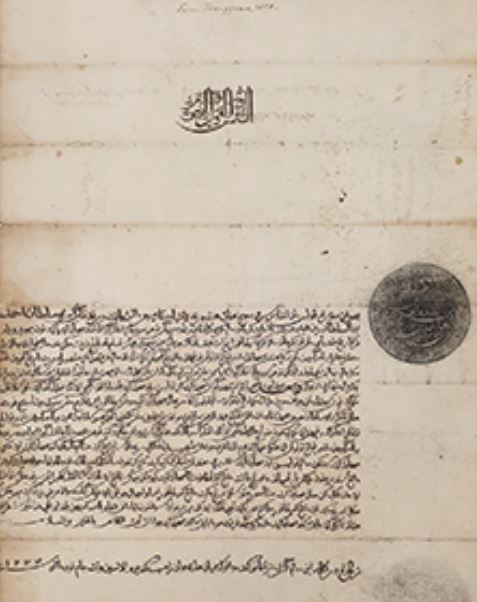

The Library of Congress and the Singapore Link

Wilkes and his team obtained a number of rare Malay and Bugis manuscripts and books with the help of the Singapore-based American missionary Alfred North.21 Some of these beautifully written manuscripts were described “as forming a collection which is said to be the largest now in being, that of Sir Stamford Raffles having been lost”.22 (Raffles’ precious collection of drawings, manuscripts, books and wildlife specimens were destroyed when the ship Fame, taking him and his family back to England, went up in flames and sank on 2 February 1824).

Initially known as the “Smithsonian Deposit”, the manuscripts and books were transferred in 1866 to the Library of Congress (LOC) in Washington D.C. – the oldest federal cultural institution in the country and reputedly the largest library in the world – forming the first documented Asian books in its collection. The materials were rediscovered in 1966 when they came to the attention of scholars. They are now part of the Southeast Asia rare collections of the Asian Division of the LOC.23

The Malay manuscripts at the LOC consist of 14 codices, six additional codices and a bound volume containing handwritten official correspondence and letters with official seals addressed to then British Resident in Singapore, William Farquhar. These were sent by heads of state in what are now Brunei, Cambodia, Malaysia and Indonesia, and are an important source of information about the early British colonial period in the region.

Among the documents are seven letters from the Raja Bendahara of Johor-Pahang (1819–22), three letters from the Pangeran Dipati of Palembang (1819–22), and a letter from Sultana Siti Fatimah binti Jamaluddin Abdul Rahman of Pamanah dated 1822. There are also numerous letters from Riau dating from 1818, as well as those from Siak, Lingga, Terengganu and other places.

Other treasures of note are two copies of the rare 1840 lithographed Mission Press edition of the Sejarah Melayu (Malay Annals) written in Jawi,24 a copy of the Hikayat Abdullah (1843) by Munshi Abdullah,25 as well as codices such as Hikayat Amir Hamzah (1838),26 Hikayat Johor (1838),27 Hikayat Panca Tanderan (1835), Hikayat Patani (1839), and a handcopied (by Munshi Abdullah) version of Kitab Tib from 1837.

Home at Last – But No Hero’s Welcome

The U.S. Ex. Ex. set off from Singapore on 26 February 1842 without the smallest ship in the fleet, the USS Flying Fish. She had been sold because her frame had weakened considerably and was unlikely to survive the perilous journey home around the Cape of Good Hope in the hurricane season.

When the USS Vincennes finally pulled into New York harbour on 10 June 1842, there was no welcome ceremony or celebration after its nearly four-year sojourn. Much had changed politically in the country in the time Wilkes and his crew were away. Instead, Wilkes and several other officers were court-martialled for various charges – including abuse of power – that distracted from the achievements of the expedition. In the end, Wilkes was found not guilty on all counts, except for using excessive punishment on his men, for which he was reprimanded.

In the days that followed, Wilkes marshalled the support of influential politicians to safeguard the discoveries of the expedition. It is to Wilkes’ credit that the first-ever national institutions in the US became home to the important collections that the U.S. Ex. Ex. had brought home, where their proper safekeeping and study could be ensured.

Despite the dent to his reputation, Wilkes was placed in charge of the expedition’s collections on 1 August 1843.28 Once again, he was deemed the best person for the job and set about preserving and preparing the collection for display in addition to preparing reports and directing the production of the expedition charts. The “Collection of the Exploring Expedition” was displayed at the Patent Office Building in Washington D.C. until 1858 when it was transferred to the Smithsonian Institution which, together with artefacts from American history, influenced the early development of the institution.

In 1844, the original and official (by the authority of Congress) publication of the expedition, titled Narrative of the United States Exploring Expedition, During the Years 1838, 1839, 1840, 1841, 1842, was assembled by Wilkes using the journals and records of his officers and others. The work was issued in five volumes with illustrations, maps and an atlas.29

The Legacy of the U.S. Ex. Ex.

The expedition was not an easy one by any measure – the gruelling four-year sea voyage saw the loss of close to 40 men and two ships, the USS Sea Gull and USS Peacock. Despite the immense challenges of the mission and the difficulties that beset Wilkes on his return, the accomplishments of the U.S. Ex. Ex. would go down in the annals of American history for its success in not only promoting American commerce and industry, but also for expanding the borders of scientific knowledge. Altogether, some 40 tons of material were brought back by the expedition, along with an astounding amount of data.

The team surveyed 280 Pacific islands, created 180 charts and logged 87,000 miles (140,013 km) without the use of modern navigation aids. The expedition also mapped 800 miles (1,287 km) of the Pacific Northwest coastline and 1,500 miles (2,414 km) of icebound and frozen Antarctica coast. A century later, during the Pacific campaign in World War II, the maps and charts created by the U.S. Ex. Ex. of the Pacific Islands (Tarawa, Gilbert and Marshall islands) would be used for the American island-hopping strategy during the war.30

The Wilkes Expedition played an important role in the development of science not only in the US but the world over. By making its research publicly available, the expedition was also instrumental in the democratisation of science. The specimens and items amassed from the expedition formed the core collection of many departments at the Smithsonian Institution, and the work of the “Scientifics” would profoundly affect the subsequent development of American science and, by extension, all scientific discovery on the global stage.

A SIZEABLE FLEET

Most European exploring expeditions in the 19th century used modestly sized ships. But the US Navy went one up by assembling a squadron of six sailing vessels with officers, crew and scientists numbering almost 500 strong, making it one of the largest voyages of discovery in the history of Western exploration. The original fleet comprised the following:

– The USS Vincennes, a fast 127-foot Boston-class sloop-of-war with a crew of 190. This was the flagship under the command of Lt. Charles Wilkes.

– The 118-foot USS Peacock, a slightly smaller, full-rigged sloop-of-war rebuilt for the expedition, and manned by a crew of 130. (When the Peacock ran aground on 18 July 1841, the USS Oregon, an 85-foot brigantine, accommodated the officers and crew of the lost ship.)

– The two-masted 88-foot brigantine USS Porpoise with a crew of 65.

– The USS Relief, a slow 109-foot supply ship with a crew of 75.

– Two small 70-foot schooners, USS Sea Gull and USS Flying Fish, each manned by a crew of 15. (Sea Gull went missing on 8 May 1839 when it was caught in a storm.)

Dr Vidya Schalk is a research scientist and currently a lecturer in the School of Materials Science and Engineering at NTU, where she teaches a module on the History of Materials. She is also researching scientific and military United States naval expeditions of the 19th century.

Dr Vidya Schalk is a research scientist and currently a lecturer in the School of Materials Science and Engineering at NTU, where she teaches a module on the History of Materials. She is also researching scientific and military United States naval expeditions of the 19th century.

NOTES

-

Wilkes, C. (1842). Synopsis of the cruise of the U.S. Exploring Expedition during the years 1838, ’39, ’40, ’41 & ’42 delivered before the National Institute by its Commander Charles Wilkes on the twentieth of June 1842 to which is added a list of officers and scientific corps attached to the expedition (p. 6). Washington, DC: Peter Force. Retrieved from Internet Archive. ↩

-

Herman Melville’s nephew, Hunn Gansevoort, was on the Wilkes expedition, but he detached with a sick ticket within 11 months. Melville incorporated aspects from the Ex. Ex. into his masterpiece, Moby Dick. ↩

-

Stanton, W. (1975). The Great United States Exploring Expedition of 1838–1842 (p. 63). Berkeley, Los Angeles; London: University of California Press. (Not available in NLB holdings). ↩

-

The roster of the civilian corps, as it appeared on the date of sailing and as it remained for the most part throughout the voyage was as follows: Charles Pickering and Titian Peale (naturalists), Joseph Couthouy (conchologist), James Dana (mineralogist and geologist), William Brackenridge (horticulturist), William Rich (botanist), Horatio Hale (philologist), Joseph Drayton and Alfred Agate (artists/draughtsmen). See Feipel, L.N. (1914). The Wilkes Exploring Expedition. Its Progress through Half a Century: 1826 1876. United States Naval Institute Proceedings, XL, pp. 1323–50. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

USS Porpoise and USS Oregon had arrived in Singapore almost a month earlier on 22 January 1842 and USS Flying Fish on 16 February 1842. ↩

-

King, H.G.R. (1979, January). Autobiography of Charles Wilkes – Autobiography of Rear Admiral Charles Wilkes, US Navy, 1798–1877, edited by W.J. Morgan, D.B. Tyler, J. L. Leonhart, and M.F. Loughlin. Washington: Naval History Division, Department of the Navy. Polar Record, 19 (121), pp. 396–397. (Not available in NLB holdings). ↩

-

Wilkes, C. (1845). Narrative of the United States’ Exploring Expedition, During the years 1838, 1839, 1840, 1841, 1842 (vols. I to V). Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard. Retrieved from Internet Archive. NLB has the condensed and abridged version published by Whittaker and Co. in London, 1845. Chapter 38 is on Singapore. This book can be retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Wilkes, 1845, vol. V, p. 411. ↩

-

Wilkes, 1842, p. 40. ↩

-

Wilkes, 1845, vol. V, p. 411. ↩

-

Wilkes, 1845, vol. V, p. 415. ↩

-

Wilkes, 1845, vol. V, p. 423. ↩

-

Wilkes, 1845, vol. V, p. 432. ↩

-

Wilkes, 1845, vol. V, p. 415. ↩

-

Wilkes, 1845, vol. V, p. 403. ↩

-

Wilkes, 1845, vol. V, p. 408. ↩

-

Wilkes, 1845, vol. V, p. 404; Colvocoresses, G.M. (1855). Four years in the Government Exploring Expedition; commanded by Captain Charles Wilkes, to the island of Madeira, Cape Verd Island, Brazil… (5th edition; p. 348). New York: J.M. Fairchild. Retrieved from Hathi Trust Digital Library. ↩

-

Wilkes, 1845, vol. V, p. 410. [Note: Muharram is the first month of the Islamic calendar. On the first day of Muharram, the Islamic new year is celebrated. The 10th day of Muharram is known as the day of Ashura, which commemorates the death of Husayn ibn Ali, a grandson of Prophet Muhammad.] ↩

-

Wilkes, 1845, vol. V, p. 428. ↩

-

Colvocoresses, 1855, p. 346. ↩

-

Of interest to note is that when the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions Singapore mission station shut down in 1843, Houghton Library of Harvard University became the repository of the remaining archives and contains many valuable manuscripts. ↩

-

Wilkes, 1845, vol. V, p. 420. ↩

-

Teeuw, A. (1967). Korte Mededelingen: Malay Manuscripts in the Library of Congress. Bijdragen tot de taal-, land-, en volkenkunde, 123 (4), pp. 517–520. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. Rony, A. K. (1991) Malay manuscripts and early printed books at the Library of Congress. Indonesia, Vol. 52, pp. 123–134. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

NLB also has the 1840 edition which has been digitised. See Munshi Abdullah. (1840). Sejarah Melayu. Singapore: Mission Press. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

NLB does not have the 1843 edition. NLB’s 1849 edition has been digitised. See Abdullah Abdul Kadir. (1849). Hikayat Abdullah. Singapore: Mission Press. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

NLB does not have the 1838 edition. NLB’s 1865 edition has not been digitised, but a microfilm copy is available. See Hikayat Amir Hamzah. (1865). [S.I.: s.n.]. (Mcrofilm no.: NL1886). ↩

-

NLB does not have the 1838 edition. Instead see this edition: Muhammad Said. (199-). Hikayat Johor dan tawarikh al Marhum Sulan Abu Bakar. London: Oriental and India Office Collections, Reference Service Division, British Library. (Call no.: Malay RCLOS 959.511903 MUH). ↩

-

Viola, H.J., & Margolis, C. (Eds.). (1985). Magnificent voyagers: The U.S. Exploring Expedition, 1838–1842 (p. 197). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. (Not available in NLB holdings). ↩

-

Only 100 copies were produced in 1844, and thus were much sought after. Beyond the five initial volumes, there were 24 additional volumes planned covering topics such as ethnography, mammalogy, ornithology, geology and botany, but not all were eventually published. ↩

-

Also known as leapfrogging, this was a military strategy employed by the Allies in the Pacific War against the Axis powers (most notably Japan) during World War II. The goal was to control strategic islands, island-by-island, using each as a base along a path towards Japan with the eventual aim of bringing US bombers within range of an invasion. ↩