Civilians in the Crossfire: The Malayan Emergency Crossfire

Ronnie Tan recounts the hardship suffered by civilians as a result of the British government’s fight against the communists during the Malayan Emergency.

China-Japan relations, which are marked by a long history of animosity that goes back several centuries, took a turn for the worse from the 1870s onwards. During the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–45), many overseas Chinese who were still loyal to their motherland, including those in Malaya and Singapore, supported China’s war efforts against Japan. Thus, when the Japanese Imperial Army invaded Malaya in December 1941, one of the first communities they targeted was the Chinese. To escape torture and persecution, many Chinese fled to the fringes of the Malayan jungles where they set up makeshift homes.

The Malayan Communist Party (MCP) had been a formidable element even before the Japanese invasion. It had been set up a decade earlier in 1930 with the primary aim of overthrowing British colonial rule. When Malaya fell to the Japanese and the British were booted out, the MCP went underground and formed the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA).

The MPAJA, which comprised mainly ethnic Chinese fighters, found a ready source of new recruits among the Chinese squatters in the Malayan jungles to fight the guerrilla war against the Japanese and their sympathisers. In a quid pro quo arrangement, the MPAJA turned to the British for military training and supplies, provided the communists with the resources they needed to defeat a common enemy.

Following Japan’s surrender in 1945 and the return of the British in the form of the British Military Administration,1 the MPAJA was formally dissolved in December that year. For the MCP, however, the problem had not gone away; the British had reinstated themselves as colonial rulers and the communists would once again resume its armed struggle.

As hostilities between the MCP and the British grew more intense, on 16 June 1948, three European planters in Perak were brutally murdered by communist insurgents. Two days later, on 18 June, a state of emergency was declared in Malaya and subsequently in Singapore on 24 June. The Malayan Emergency would last for the next 12 years, ending only on 31 July 1960.

One of the first things the MCP did was to revive the MPAJA, rebranding it as the Malayan People’s Anti-British Army (MPABA), and subsequently renaming it the Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA) in 1949.2

To secure access to supplies of ammunition and food, the communists began intimidating, torturing and even murdering civilians who refused to support their anti-colonial activities. By October 1948, the MNLA had killed 223 civilians, most of whom were Chinese, “for their reluctance to support the revolution”.3 To counter the communist threat, the British put in place the Briggs Plan, a strategy aimed at defeating the communist insurgency.4

The Briggs Plan

One of the chief aims of the Briggs Plan was to deprive the communist guerrillas of sources of support and sustenance. The plan was described as “a policy of starving [the communists] out, coupled with ceaseless pressure by security forces operating in small patrols… intended to deprive the MRLA [Malayan Races Liberation Army]5 everywhere in the country of every necessity of life from food to clothes, and every article for their military aims from printing materials to parts for radio receiving and transmitting sets, weapons and ammunition”.6

Shopkeepers in operational areas for instance were not allowed to store excess quantities of canned and raw food that were designated as “restricted”. In addition, they had to keep detailed records of all customers and their purchases, and not sell any kind of food item unless the customer produced an identity card. Restricted items included “all types of food, paper, printing materials and instruments, typewriters, every drug and medicine, lint bandages and other items; torch batteries, canvas cloth, and any clothing made from cloth as well as cloth itself”.7 Even cigarettes and beverages like coffee and tea were restricted. The regulations were so stringent that in some instances, people were not allowed to stock more than a week’s supply of rice.

Relocation to “New Villages”

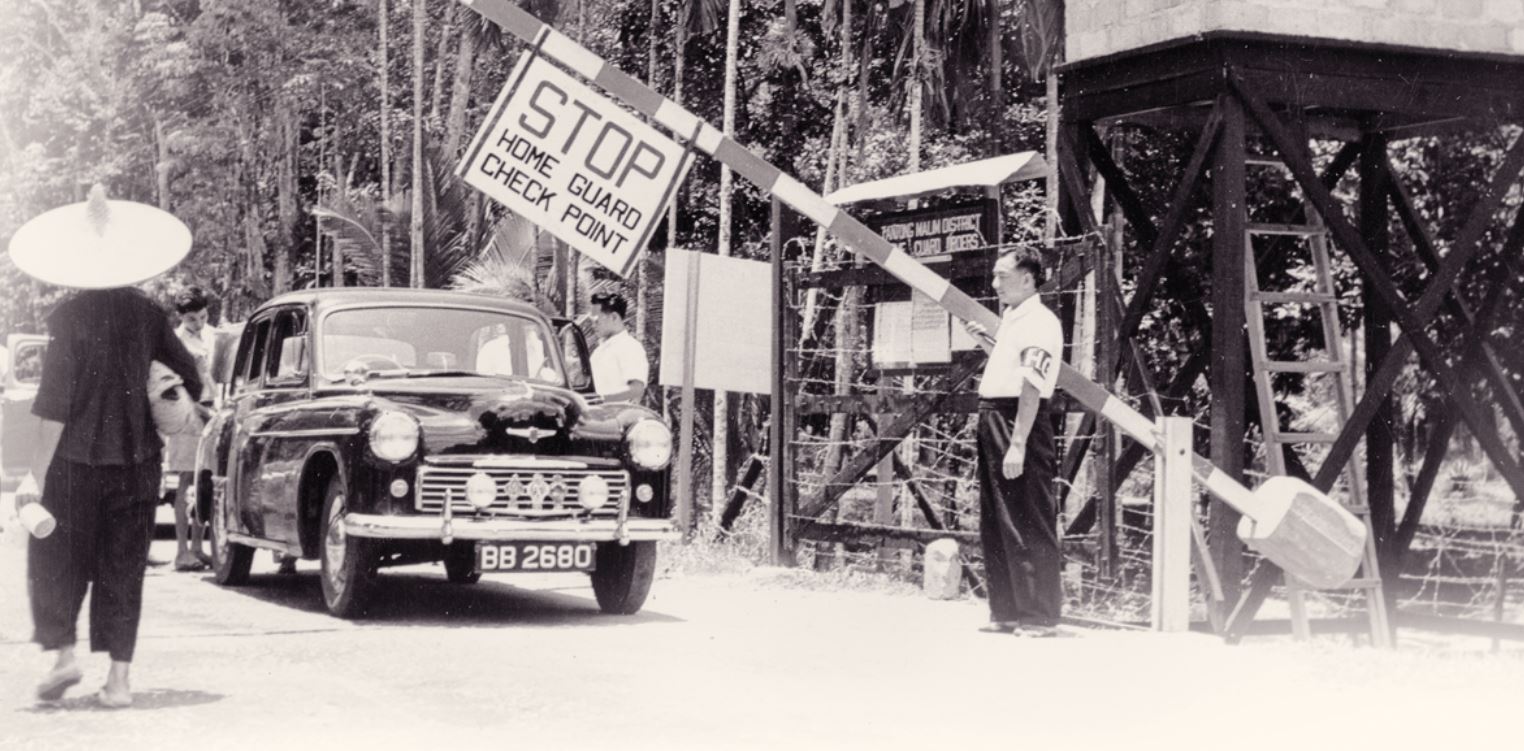

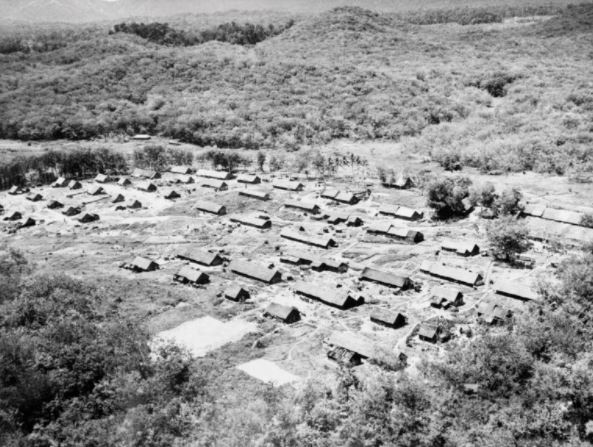

To further ensure that the communist guerrillas were isolated from the main population, the predominantly Chinese villagers living in squatters in the jungle fringes were relocated to settlements called “New Villages”. These villagers were “strategically sited with an eye to defence, protected with barbed wire and guarded by a detachmentof Special Constables, until they were each able to form their own Home Guard units”.8

Each relocation was shrouded in secrecy and the villagers were not notified beforehand. According to British military historian Edgar O’Ballance, “secrecy was essential to success, otherwise the squatters would have disappeared into the jungle in mass flight”.9 The operation usually began before dawn, with troops and police surrounding the squatter area. The villagers were then moved en masse, along with their belongings and livestock, using one truck per family to the New Villages scattered throughout Malaya.10

Most villagers were caught unawares and “stupefied by shock” at the sudden move, protesting that they should not be forced to relocate as they had never helped the communists. Some tried delay tactics, for example, by claiming that they had to round up their livestock in the jungle, or that they were ill.11 Most were persuaded to move only when told that the plots of land in the New Villages would be allotted on a first-come-first-served basis.12 By mid-1951, around 400,000 villagers had been resettled in such New Villages. The reality was, however, far from rosy for these new settlers.

Once settled in the New Villages, people who entered or left the villages were subject to stringent checks by armed security personnel guarding the gates around the clock. This was to ensure that the villagers could not secretly send supplies to the guerrilla fighters. Plantation workers, whom the communists targeted, also had to be home by 3 pm daily and were not allowed to leave the village from 5 pm until 6 am the next day.

These measures had an adverse impact on the livelihoods of the people. Apart from having to wait in long queues to be searched by security officers, those who worked outside the villages were prohibited from taking their mid-day meals with their families. In fact, all they could have on them was a bottle of water; tea or coffee was not allowed to be brought out of the villages “for these would be welcome drinks to the enemy”.13 Those in the trucking business, too, were affected as the regulations meant that lorries could only stop in certain areas, which in turn impeded the supply of food to small villages.

Despite the best efforts of the British to cut off the supply of food and other essential items, the communists still managed to infiltrate and obtain supplies from people residing in these New Villages. The presence of armed security personnel at the gates and the severe consequences that awaited those caught red-handed were not enough of a deterrence. Communist sympathisers and those coerced into aiding the communists “invested extraordinary tricks to smuggle rice, often to relations in the jungle”14 (see textbox below).

There were also reported cases of crimes committed by the security forces against the villagers. Under the pretence of checking for possible smuggling attempts, some police officers were known to have outraged the modesty of young girls by strip-searching them.15

The forced resettlement in the New Villages also led to a sense of social dislocation among its inhabitants. Livelihoods were disrupted, and many lost lucrative sources of income and had to find alternative means of survival. In some cases, people who were separated from their families and loved ones suffered from anxiety, despair and hopelessness.

Punishment for Abetting the Communists

Severe penalties were meted out to those caught for not divulging information on communist activities to the authorities or for helping the communists, with the punishments often disproportionate to the actual crimes committed.

One particular incident stands out. Collective punishment was meted out to some 20,000 people living in Tanjung Malim, a town in Perak, which already had a reputation for being a hotbed of communist activity since the start of the Emergency. This took place after an incident on 25 March 1952 when a group of civilian officers, accompanied by security personnel, were ambushed on their way to repair a nearby waterworks that communist guerrillas had sabotaged. Twelve civilian personnel were slain and eight wounded in the ambush.

Since the villagers were not forthcoming with information about the perpetrators, General Gerald Templer, who was then General Officer Commanding and Britain’s High Commissioner to Malaya, stripped the town of its status as a district capital and imposed a 22-hour curfew every day for a week. Shops were permitted to open only two hours a day, people were banned from leaving town, schools were closed, bus services were ceased and rice rations were reduced.

To provide a secure way for villagers to supply information, the authorities handed out questionnaires to the head of each household. The completed forms were then brought to Kuala Lumpur in sealed boxes and reviewed by Templer himself in the presence of the town’s representatives. The exercise resulted in the ambush and killing of the communist guerrilla leader in Tanjung Malim, the detention of 30 Chinese shopkeepers and several arrests. Only then were curfew and restrictions lifted in the town.

Even harsher punishments were exercised on at least six other occasions in different parts of Malaya:

- A 70-year-old man, Chong Ngi, was given a five-year prison sentence for providing communist guerillas in an unidentified part of Malaya with food and rice.16

- Hee Sun, a resident of Kulai Besar New Village in southern Johor, was sentenced to three years’ imprisonment for being found in possession of one kati and one tahil (478 g) of rice intended for the guerrillas.17

- A 44-year-old rubber tapper, Wong Pan Sing, from Gombak, Selangor, was sentenced to 10 years’ jail for possessing five gantangs (14.7 kg) of uncooked rice, sugar, cigarettes and Chinese medicine.18

- Phang Seng, a farmer from Kelapa Sawit New Village in southern Johor, was jailed three years for being caught at the village gate without a valid permit for carrying six tahils (227 g) of rice on him. When apprehended, he could not give a satisfactory explanation as to why he had uncooked rice with him because he claimed “he could not speak a word of Malay”.19

Coercion from Communists

Many people living in the New Villages were caught between a rock and a hard place. Apart from mounting pressure from the police, they were also not entirely safe from the clutches of the communist insurgents. As mentioned earlier, those who were either neutral or opposed the goals of the communists were coerced into aiding them or faced reprisals – even death – if they did not cooperate. For instance, a villager in the northern state of Kedah was killed by three communist guerillas for refusing to buy them food.20

Hee Sun of Kulai Besar New Village, for example, had the misfortune of encountering communist guerrillas while working and was warned, in no uncertain terms, that he would be killed if he did not supply them with food. He did not report this incident to the police because he feared for his life and that of his family members as the communists knew where he lived.

As for Wong Pan Sing from Gombak, Selangor, he was threatened with death if he did not use the $18 that three communist guerillas gave him to buy “uncooked rice, sugar, cigarettes and Chinese medicine”.21 Such hapless civilians had little choice in these situations because the communists usually made good their threats of reprisal.

Even children and youths were not spared. On 20 June 1951, it was reported that an 11-year-old Malay boy from Bentong in Pahang was forced off his bicycle at gunpoint, “tied and blindfolded and forced some distance into the lallang” by communist insurgents and persuaded to work for them as a courier and supplier.22 The boy refused and managed to escape from his captors a short while later.

In another instance, on 26 October 1954, 17-year-old rubber tapper named Low Hoon “pleaded guilty to attempting to supply one tin of milk beverage, two bottles of curry powder, dried chillies and salt fish” to the communists along Cheras Road in Kuala Lumpur.23 Low claimed that the communists had threatened to kill him if he did not comply with their demands to buy the items with the money they had forced upon him.

In order to implement an administration system in the New Villages, government officials urged the villagers to stand for election as council members. However, it was difficult to persuade the villagers to do so as they were “terrified that the communists would see their election as an anti-communist stand and would kill them the moment they left the village”.24 Even when the elections went ahead and people were voted in as council members, some were so terrified for their lives that they “bolted for Singapore and safety”.25

Such fears were not unfounded, for in the town of Yong Peng in central Johor, two such councillors had their arms hacked off. The murder of another village committee member in Kebun Bahru, northern Johor, also underscored the probability of severe reprisals awaiting those whom the communists deemed to be pro-British.

Lost in Translation

Language barriers between the local authorities and villagers also proved problematic, as illustrated by the aforementioned trial of Phang Seng. In court, Phang pleaded ignorance and claimed he did not know that a permit was needed to bring rice out of the village to cook in the pig sty where he worked. The rice was intended for two of his four sick, young children. He also claimed that he could not give a satisfactory answer to the Malay guard on duty because he could neither speak nor understand Malay.

The language barrier became a subject of ridicule when British officials in Malaya tried to communicate with the grassroots. After communist insurgents descended on Kulai New Village in southern Johor, taking away 20 shotguns as well as ammunition from the local guards without a fight, Templer unleashed his fury on the villagers by describing them as “just a bunch of cowards”, even berating them with the use of an expletive. Unfortunately, the translator totally missed the point and reportedly said, “His Excellency says that your fathers and mothers were not married when you were born”.26

Templer, apparently ignorant that his words were lost in translation, continued to use the same expletive to describe himself, saying that he could be even more ruthless than the communist guerrillas. Once again, the message was lost in translation when the translator announced to all present that Templer himself admitted that his parents were also not married to each other when he was born!27

Post-Templer Era

By the time Templer left Malaya and returned to the United Kingdom in 1954, the authorities had already gained the upper hand in the fight against the communists. It was clear that the Briggs Plan had proven effective in cutting off supplies to the communists; it not only hurt them physically and militarily, but their morale was also severely affected. The dire lack of food caused some communist insurgents to surrender to the authorities, while dozens more perished in the jungles. Many guerrillas were killed while foraging for food near the New Villages. In one instance, two dead communists in their mid-30s were found with “three wild jungle yams and a green papaya – all inedible”.28 It was reported that some guerrillas even resorted to killing monkeys for meat in order to survive.

HOW TO OUTSMART THE AUTHORITIES

These are some of the ingenious methods that people in the New Villages used to smuggle out essentials to the insurgents:

– The bicycle frame was a favourite tool for smuggling supplies. In a village near Kluang in central Johor, two soldiers who dismantled a bicycle belonging to a nine-year-old boy found rice and antibiotic pills hidden in the bicycle frame. The boy drew suspicion because he had been learning to ride a bicycle, “or pretending to, for the past week”, and was always doing so by riding beyond the security checkpoints.29

– In another village, an old woman walked past through the checkpoint daily, carrying two buckets of pig swill that hung from a bamboo pole balanced on her shoulders. When the suspicious police officers “put their hands daily into the filthy mess”, they found nothing.30 A month later the officers realised they had been hoodwinked when they found rice hidden in the hollow bamboo pole instead.

– Medicine and other items were concealed under raw pork as the Malay constables would not touch these receptacles.

– Night soil carriers squirrelled items out of the villages by stashing them in false bottoms of their buckets, while rubber tappers did the same by hiding rice at the bottoms of pails containing latex.

– Women pretended to be pregnant and wore big brassieres where rice could be stashed, while men strapped bags of rice to the inside of their thighs and wore loose pants.

– Those living near the fences surrounding the New Villages often placed supplies near the fences where the communist guerrillas could easily retrieve.31 Planks were sometimes placed across the fences or holes were made in the fences so that the guerrillas could enter and leave the villages easily.

The communists’ efforts to grow their own vegetables in the jungle also proved futile: the neat rows of vegetables were easily spotted from the air by British Royal Air Force (RAF) aircraft and bombed. After realising their mistake, the communists began planting vegetables in a haphazard manner like the Orang Asli, but the RAF still managed to find and destroy these agricultural plots.32

Chin Peng, the MCP leader during the Malayan Emergency, admitted just as much in his memoir when he said that the Briggs Plan was the MCP’s Achilles heel.33 Recovered communist documents revealed that the “shortage of food in various places prevented us [the communists] from concentrating large numbers of troops and launching large-scale operations” and that “they must guard against quarrelling over the table and stealing each other’s food. People with huge appetites should be admonished and taught to develop self-restraint”.34

Even the restriction to beverages such as coffee affected some: a note written by a communist insurgent lamented that he had not drunk coffee for over two months, and when he finally had the good fortune to find some, there was not enough sugar to sweeten the treat.

As for the civilians who suffered through it all, the psychological impact stayed with them long after the Emergency officially ended on 31 July 1960. They remained suspicious of strangers and had difficulty accepting help from outsiders. Even after the barbed wire surrounding the New Villages had been dismantled and outsiders started moving in, there were frequent altercations between former residents and the newcomers.35

On a positive note, the communists never regained their foothold in Malaya. They were put on the defensive and eventually retreated to the Thai-Malaysian border. On 2 December 1989, the MCP agreed to “disband and end its struggle against the Malaysian forces” by signing a peace accord with the Malaysian and Thai governments in Hat Yai, southern Thailand.36

Ronnie Tan is a Senior Manager (Research) with the National Library, Singapore, where he conducts a research on public policy as well as historical, regional and library-related issues. His other research interests include Malayan history, especially the Malayan Emergency (1948-60), and military history.

Ronnie Tan is a Senior Manager (Research) with the National Library, Singapore, where he conducts a research on public policy as well as historical, regional and library-related issues. His other research interests include Malayan history, especially the Malayan Emergency (1948-60), and military history.

NOTES

-

The British Military Administration was the interim military government established in Singapore and Malaya during the period from the Japanese surrender to the restoration of civilian rule on 1 August 1946. ↩

-

Hack, K. (1999, March). “Iron claws on Malaya”: The historiography of the Malayan Emergency. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 30 (1), 99–125, p. 99. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Paul, C., et al. (2013). Malaya, 1948–1955 case outcome: COIN win. In Paths to victory: Detailed insurgency case studies (p. 55). Santa Monica: RAND Corporation. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Named after Lieutenant-General Harold Rawdon Briggs (1894–1952), who devised the strategy. Although having retired from the British Army in 1948, he was recalled to active duty in 1950 and became Director of Operations in Malaya during the Malayan Emergency. ↩

-

The Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA) was often mistranslated as the Malayan Races Liberation Army (MRLA). ↩

-

Miller, H. (1981). Jungle war in Malaya: The campaign against communism, 1948–60 (p. 73). Singapore: Eastern University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.5 MIL). ↩

-

O’Ballance, E. (1966). Malaya: The Communist insurgent war, 1948–1960 (p. 109). London: Faber and Faber Limited. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.5 OBA-[JSB]). Amenities such as water, electricity, medical facilities and schools were provided for settlers in the New Villages. The villagers were run by locally elected village councillors. See Barber, N. (1971). The war of the running dogs: How Malaya defeated the communist guerrillas, 1948–60 (p. 103). London: Collins. (Call no.: RDLKL 959.5 BAR). ↩

-

O’Ballance, 1966, p. 110. ↩

-

Barber, N. (1971). The war of the running dogs: How Malaya defeated the communist guerrillas, 1948–60 (p. 103). London: Collins. (Call no.: RDLKL 959.5 BAR). ↩

-

O’Ballance, 1966, p. 110. ↩

-

Koya, Z. (1998, August 1). Villagers’ sacrifice to beat the reads. New Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from ProQuest Central via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Aged man jailed for consorting. (1951, June 21). Singapore Standard, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Had food for bandits, gets 3 years’ jail. (1952, August 21). Singapore Standard, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Bandit supplier gets ten years. (1952, September 12). Singapore Standard, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore Standard, 12 Sep 1952, p. 5. ↩

-

Terrorists kill man who said no. (1954, December 17). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore Standard, 12 Sep 1952, p. 5. ↩

-

Youth defies bandits. (1951, June 20). Singapore Standard, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Gaoled when I told police my son gave food to bandits. (1954, October 27). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Cloake, J. (1985). Templer: Tiger of Malaya: The life of Field Marshall Sir Gerald Templer (p. 272). London: Harrap. (Call no.: RSING 355. 3310942 TEM.C). ↩

-

Starving reds killed in ambush. (1958, July 1). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

‘Operation Starvation’ hits reds. (1951, September 23). The Straits Times, p. 5; Malaya’s reds are still being fed. (1952, April 17). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Orang Asli are the indigenous people of Peninsular Malaysia. They, too, suffered during the Emergency. Thousands were believed to have perished during this period. ↩

-

Chin, P. (2003). My side of history (p. 270). Singapore: Media Masters. (Call no.: RSING 959.5104092 CHI). ↩

-

Food: Reds squeal. (1953, July 1). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

New Straits Times, 1 Aug 1998, p. 7. ↩

-

Hassan Kalimullah. (1989, December 1). CPM to destroy all arms and ammunition in 7-point pact. The Straits Times, p. 23. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩