Dieppe Barracks: “Our Little Kingdom” in Sembawang

Military camps and training areas comprise a significant portion of Singapore’s land use. What can a single camp tell us about Singapore’s geopolitical history? A lot, as it turns out, says Chua Jun Yan.

Travelling along Sembawang Road, you will pass several military installations, including Nee Soon Camp, Khatib Camp and Sembawang Camp. At the end of the road is Sembawang Shipyard, site of the former Singapore Naval Base and the cornerstone of Britain’s ill-fated Far East defence strategy before World War II.1

This military corridor in the north of Singapore, whose roots go back to the colonial period, is historically significant. Of the various camps along this stretch, Dieppe Barracks (pronounced “dee-ap”) stands out because it housed the last permanent foreign presence in Singapore until 1989, bearing witness to the geopolitical transformations of the 20th century. Today, the barracks is home to the HQ Singapore Guards and the HQ 13th Singapore Infantry Brigade of the Singapore Armed Forces (SAF).

Endings and New Beginnings

Constructed between 1965 and 1966 for British troops based in Singapore, Dieppe Barracks was originally part of the new but short-lived Far East Fleet Amphibious Forces Base.2 Even as the Malayan Emergency (1948–60)3 gave way to Konfrontasi4 with Indonesia (1963–66), Britain maintained its military position on the island after Singapore became an independent sovereign nation in August 1965.

The first occupants of Dieppe Barracks was the 40 Commando unit of the British Royal Marines, which had relocated from Borneo to its new base in Singapore. Incidentally, it was the Royal Marines Commando unit’s service in France during World War II that gave Dieppe Barracks its name.

In 1942, the Royal Marines Commandos had participated in the bold but disastrous Operation Jubilee, better known as the Dieppe Raid, in which some 6,000 Allied troops – comprising Canadian soldiers, British commandos and US Rangers – mounted an assault on the German-occupied port of Dieppe in France. Less than 10 hours after the first amphibious landings on 19 August took place, nearly 60 percent of the men had been killed, wounded or captured.5

Given the inglorious and humiliating defeat at Dieppe, why did the British choose to name its new military installation in Singapore after the raid?

Historical studies on the Dieppe Raid offer a clue. In the 1960s, military historians had vigorously debated the necessity of the Dieppe Raid. Revisionist scholars argue that the raid resulted from inexcusable shortcomings in the Allied pre-operation planning and represented an avoidable loss of human life. By contrast, orthodox historians of World War II hold the view that the Dieppe Raid was a necessary rehearsal for the D-Day landings,6 which ultimately liberated Europe from Adolf Hitler and the tyranny of Nazi occupation.

“Honour to the brave who fell. Their sacrifice was not in vain,” wrote Winston Churchill in The Hinge of Fate, the fourth installment in his multivolume history of World War II.7 Seen in this light, the etymology of Dieppe Barracks might have represented an intervention in a broader debate about World War II’s reputation as “the good war”, at a time when the British Empire was rapidly losing its lustre and the Vietnam War was becoming a debacle for the free world.

Within this context of global strategic flux, the British did not remain at Dieppe Barracks for long. In July 1967, then British Prime Minister Harold Wilson announced plans to withdraw all British troops from Singapore by 1975. The following year, Wilson brought forward the withdrawal deadline to 1971 as his Labour government grappled with a floundering domestic economy back home. The unexpected pullout of British troops would not only create problems for Singapore’s national security but would also put a huge dent in its economy: it was estimated that more than 20 percent of Singapore’s gross national product came from British military bases on the island.

That Dieppe Barracks was constructed just a year before Wilson made the announcement also indicates how unexpected this move was, reflecting the wider uncertainty about Britain’s role in the world at the time.8 The decline of British preeminence in Asia might have been gradual, but the final retreat was ultimately unpredictable, as Dieppe Barracks attests.

The departure of British forces from Dieppe Barracks and the arrival of the New Zealanders embodied the wider geo-strategic changes that were taking place in the 1970s. In 1971, the 1st Battalion of the Royal New Zealand Infantry Regiment (1 RNZIR) replaced the British commandos at Dieppe Barracks, marking a shift from imperial defence to regional security as the prevailing strategic paradigm. During a 1975 trip to New Zealand, then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew credited New Zealand’s presence with creating “a psychological sense of stability”, giving Singapore time to develop its own defence capabilities.9

In 1975 and again in 1978, the New Zealand government sought to withdraw its troops from Singapore. Given Singapore’s growing defence capabilities and the apparent stability in the region, the Kiwi presence appeared increasingly anachronistic.10 However, New Zealand’s plans were foiled by the escalating Cold War tensions between the Soviet Union and the United States, specifically, the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia in December 1978 and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in December 1979.

In 1979, Dieppe Barracks bore witness to one of the biggest humanitarian crises of the period: the exodus of Vietnamese boat people following the end of the war in Indochina. On 14 April, then New Zealand High Commissioner G.C. Hensely hosted 51 Vietnamese refugees, including 18 children – who had been granted asylum by Auckland – at Dieppe Barracks during their eight-hour transit in Singapore.11

The refugees had arrived in Malaysia by boat six months earlier and were housed at the refugee camp on Pulau Bedong, off the coast of Terengganu. At Dieppe Barracks, they were treated to food and drinks, and the children watched colour television for the first time. Given Singapore’s limited size and resources, the government was firm in denying refuge to the Vietnamese, but had granted special permission to the High Commissioner to entertain the refugees at Dieppe Barracks, reflecting its liminal position as a foreign base on Singaporean soil.

With the end of the Cold War in the late 1980s and the growth of the SAF, the Kiwi presence at Dieppe Barracks seemed increasingly irrelevant. Towards the end of 1986, New Zealand announced it would withdraw all its infantrymen from Singapore by 1989. On 21 July that year, as the “Last Post” played in the background, the New Zealand flag was lowered over Dieppe Barracks for the last time.12 A few months later, an auction was held at the barracks to dispose of more than 60 Kiwi vehicles.13 For the second time in just over two decades, Dieppe Barracks had changed ownership, but this time to the SAF and not to a foreign entity.

Rugby Diplomacy and Geopolitical Golf

While Singapore enjoyed relative peace and stability from the late 1960s, the foreign military presence at Dieppe served as an important conduit for defence diplomacy and cultural exchange. Sports facilities in and around the barracks provided the troops with recreational activities, fostered informal contact between military leaders, and engendered positive civil-military relations.

After Britain’s Royal Marines Commandos moved into Dieppe Barracks in 1967, they built a nine-hole golf course, which would evolve into today’s Sembawang Country Club – a club that is presently affiliated to the SAF. The early course was primitive: it was “short and carved out of an area of poor soil”, and was so hilly that it was informally known as the “commando course”.14 However, Singaporean leaders perceived golf as an opportunity to cultivate friendly relations with foreign military officials.

During the early 1970s, then Minister for Defence Goh Keng Swee urged senior SAF officers to pick up golf in order to facilitate interactions with their foreign counterparts. In the late 1970s, the SAF redeveloped the golf club, before taking it over from the New Zealand forces.15

Similarly, rugby also helped to forge closer ties between Singapore and New Zealand. When the New Zealand forces occupied Dieppe Barracks in 1971, the rugby pitch along Sembawang Road became the centrepiece of public diplomacy between the two countries. From 1971 to 1989, Dieppe Barracks hosted hundreds of rugby matches, often between the Kiwis and local teams. These efforts strengthened New Zealand’s soft power and enhanced people-to-people ties between the two countries.

In 1979, for instance, the Singapore Combined Schools’ rugby squad described a match and training clinic with the New Zealand All Blacks as a “dream date”, held in what The Straits Times called “a truly New Zealand atmosphere at the Dieppe Barracks”.16 In the Singaporean schoolboy’s imagination, Dieppe Barracks was a portal into the distant land of New Zealand.

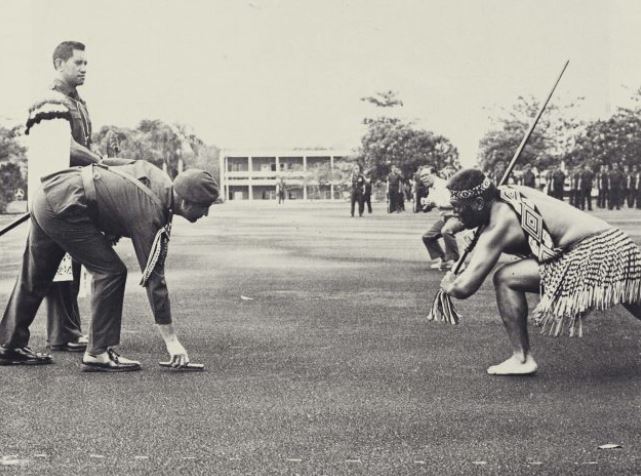

Aside from sport, Dieppe Barracks also boasted a Maori Cultural Group, which established its base at Marae of Tumatauenga, a sacred meeting place located within the perimeters of the camp. Apart from catering to the spiritual needs of the soldiers, the Maori group toured Southeast Asia to showcase New Zealand’s heritage and culture. In 1981, for instance, it visited Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia and Brunei, performing at the Sabah Centenary Expo and appearing on Radio Television Malaysia. Similarly, the Kiwi regimental band performed at different venues around the region, enhancing New Zealand’s visibility and prestige.17

Against this backdrop, the SAF developed strong relations with New Zealand troops at Dieppe Barracks. In 1974, the SAF’s elite unit, the 1st Commando Battalion, established ties with 1 RNZIR, visiting each other’s units and holding friendly sports matches. The two countries formalised this partnership in 1982 and thereafter held an Alliance Day parade at the barracks annually. At the 1986 New Zealand Day parade, then Second Minister for Defence Yeo Ning Hong told the men of 1 RNZIR that the SAF was “proud to be associated with a unit as distinguished as [theirs]”, reflecting the fruit of years of defence diplomacy.18

As recently as May 2019, Singapore and New Zealand signed a joint declaration to deepen bilateral cooperation in four areas, including defence and security. At a press conference, Prime Minister of Singapore Lee Hsien Loong and Prime Minister of New Zealand Jacinda Ardern described the two countries as “natural partners”.19 In fact, this “natural” partnership reflected a decades-long history of mutual goodwill, some of which had been fostered at Dieppe Barracks since the 1970s.

Life in Dieppe Barracks

For the most part, a jocular mess culture prevailed at Dieppe Barracks. Archival video footage features barebodied servicemen practising drills, playing squash or basketball, lifting weights and wolfing down copious amounts of food at the cookhouse. The journal of 1 RNZIR described the camp as “our little kingdom… situated among golf courses, rugby fields, bars, messes, clubs and more bars”.20 For young Kiwi soldiers, an overseas posting also presented a chance to see the world and travel across Southeast Asia.

Christmas was always a special occasion at Dieppe Barracks, eagerly anticipated by the servicemen each year. In 1970, 160 children of the Royal Marines watched in awe as a British commando dressed as Santa Claus parachuted from a helicopter over the barracks, bearing presents for the children.21 With the New Zealand troops, the tradition was for its senior officers to serve the junior ranks at Christmas parties held in the messes.22

To be sure, life in Dieppe Barracks was not always rosy, reflecting the emotional and psychological challenges of long-term overseas deployments during peacetime. Indeed, the 1 RNZIR journal introduced an “advisory service” in 1975, noting that the “pressures of modern day living in Singapore can be considerable, leading to stress, tension and worry”.23 Far away from home and without a specific mission, there was a high chance of young soldiers becoming bored and restless. Indeed, in 1972, a soldier set fire to the sacred Maori meeting place in Dieppe Barracks and was sentenced to one year’s detention. During his trial, the soldier said that he had gotten up to mischief simply because he had wanted to be sent home.

Almost a decade later, two New Zealand soldiers were each sentenced to three years’ jail and given three strokes of the cane by a Singaporean district court for selling cannabis to fellow servicemen (they had earlier pleaded to be court-martialled in order to escape caning). According to a lawyer, the drug problem at Dieppe Barracks “had reached unmanageable proportions despite efforts by military authorities”, leading the New Zealand army to hand over jurisdiction of the case to Singapore.24

An Inherited Legacy

Why does this story of Dieppe Barracks matter? Much of Singapore’s military history remains focused on World War II and the Japanese Occupation, and scholars have increasingly called for greater attention to our more recent past.25

Military spaces physically express the colonial, post-colonial and neo-colonial processes that have shaped Singapore’s history and landscape over the decades. Given that foreign military bases in Singapore were a major driver of the economy in the late 1960s and employed some 25,000 locals,26 it is impossible to understand the social, economic and cultural changes that had taken place here without reference to the vast numbers of soldiers and seamen who passed through this island from the 19th century to the present day.

I myself completed national service in Dieppe Barracks from 2018 to 2019, and in some small way was part of its geostrategic history and destiny. From British commandos to New Zealand infantry soldiers and finally to me and my fellow national service mates, places like Dieppe Barracks have witnessed and stood sentinel to the transformations of Singapore we have seen over the years.

Chua Jun Yan graduated from Yale University with a Bachelor of Arts in History. He enjoys researching local and community histories in Singapore, and has a particular interest in postwar urban cultures.

Chua Jun Yan graduated from Yale University with a Bachelor of Arts in History. He enjoys researching local and community histories in Singapore, and has a particular interest in postwar urban cultures.

NOTES

-

The British considered Singapore the most ideal location for a new naval base to house a fleet of the Royal Navy and to counter the threat posed by the Japanese military to its empire in the Far East. It was a rude shock when the impregnable fortress that was Singapore fell to the Japanese within a matter of days, from 3–15 February 1942. ↩

-

After the Suez Crisis, or the Second Arab-Israeli War, in 1956 exposed British military vulnerabilities, Britain developed a new expeditionary force to protect its interests “east of Suez”. Originally deployed in the Persian Gulf, the force was eventually based in Singapore. The Far East Fleet Amphibious Forces Base in Singapore housed Kangaw Barracks (today’s Khatib Camp) to the south, Dieppe Barracks to the northeast, and an airfield between the two facilities. ↩

-

A state of emergency was declared in Singapore on 24 June 1948, a week after an emergency was launched in Malaya following a spate of violence by insurgents from the Malayan Communist Party. The guerilla war to overthrow the British colonial government and install a communist regime lasted for 12 years, from 1948–60. ↩

-

Konfrontasi, or the Indonesia-Malaysia Confrontation (1963–66), was a conflict started by Indonesia to protest against the formation of the Federation of Malaysia. It was marked by armed incursions, bomb attacks as well as acts of subversion by Indonesians on Malayan territory (including Singapore). ↩

-

Schreiner, C.W., Jr. (1973). The Dieppe Raid: Its origins, aims, and results. Naval War College Review, 25 (5), 83–97. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResoruces website. ↩

-

The Normandy landings, codenamed Operation Neptune and commonly known as D-Day, refer to the Allied invasion of Normandy on the northern coast of France on 6 June 1944. The operation liberated France and later western Europe from Nazi control. ↩

-

Churchill, W. (1950). The hinge of fate (p. 459). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. (Call no.: RCLOS 940.53 CHU-[JSB]). The other titles in the six-volume series, “The Second World War”, are: The Gathering Storm (vol. 1), Their Finest Hour (vol. 2), The Grand Alliance (vol. 3), Closing the Ring (vol. 5), and Triumph and Tragedy (vol. 6). ↩

-

Lim, I.A.L. (Interviewer). (1990, January 16). Oral history interview with Chris Manning-Press (Lieutenant-Colonel) [Transcript of recording no. 001146/3/2, p. 32]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Ministry of Culture. (1975, April 7). Transcript of question-and-answer session following the prime minister’s address to the New Zealand National Press Club in Wellington on 7 April 1975. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

McCraw, D. (2012). Staying in Singapore? New Zealand’s Third Labour Government and the retention of military Forces in Southeast Asia. New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies, 14 (1), 1–17. Retrieved from New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies website. ↩

-

Kutty, N.G. (1979, April 15). Treat for 51 Viet refugees on their way to Auckland. The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Grand farewell parade by New Zealanders. (1989, July 21). The Straits Times, p. 19. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Kiwi vehicles for auction. (1989, July 29). The Straits Times, p. 19. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tan, T. (2016). Sembawang Country Club: An early history (pp. 1–8). Retrieved from Sembawang Country Club website. ↩

-

Grant, D. (1977, October 1). How it all came about. The Business Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Robert, G. (1979, November 30). Dream date for schoolboys. The Straits Times, p. 38. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The red diamond. 1 RNZIR Journal. (1982). ↩

-

Ministry of Communications and Information. (1986, February 5). Speech by Dr Yeo Ning Hong, Minister for Communications and Information and Second Minister for Defence, at the 1986 New Zealand Day Parade at Dieppe Barracks, Sembawang, on Wednesday, 5 February 1986 at 6.00 pm. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Jalelah Abu Bakar. (2019, May 17). Singapore and New Zealand are ‘natural partners,’ say PMs. Retrieved from CNA website. ↩

-

Journal of the First Battalion, the Royal New Zealand Infantry Regiment. (1985). Singapore: First Battalion Royal New Zealand Infantry Regiment. (Call no.: R 356.1109931 RNZIRF). ↩

-

160 watch santa drop from the skies. (1970, December 18). The Straits Times, p. 15. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tan, D. (1986, December 21). One place where you can’t pull rank. The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

1 RNZIR. (1975). Singapore: First Battalion Royal New Zealand Infantry Regiment. (Call no.: 356.1109931 RNZIRF). ↩

-

Fernandez, C. (1981, November 26). Two NZ soldiers jailed for peddling drugs. The Straits Times p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ong, W.C. (2019, February 13). Singapore’s military history: Look beyond World War II. RSIS Commentary, 21, 1–4. Retrieved from S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies website. ↩

-

Lee begins talks to avert total British pull-out by 1975. (1967, June 27). The Straits Times p. 18. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩