Trial by Firing Squad

In 1915, sepoys in Singapore revolted against their British officers in a bloody rebellion. Umej Bhatia recreates the final moments of the mutineers as they pay the ultimate price for their actions.

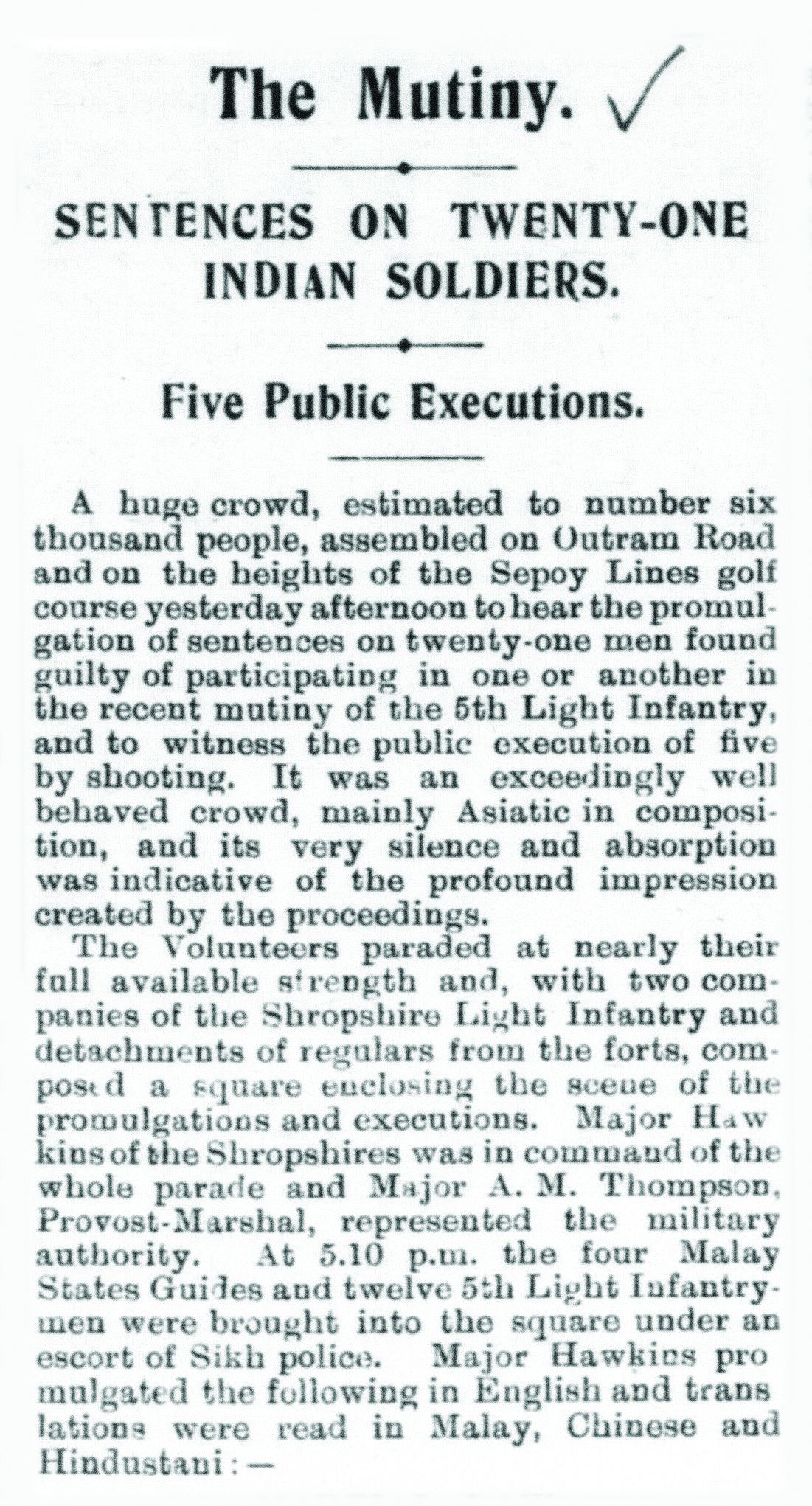

On 15 February 1915, a mutiny broke out among sepoys (Indian soldiers) of the 5th Light Infantry Regiment based in Singapore. The mutiny lasted almost a week and claimed the lives of 44 people – British soldiers and civilians, as well as Chinese and Malay civilians. More than 200 sepoys were tried by court martial and received varying sentences, while more than 47 were publicly executed at Outram Prison. Initially portrayed as a minor event confined to Singapore, Umej Bhatia’s recently published book Our Name is Mutiny argues that the event was part of a larger movement rebelling against the British Raj. This abridged extract is from the first chapter of Bhatia’s book, which deliberately uses a novel-like narrative to recount the events.

The end is always a good place to start. Even in the face of its own extinction the mind believes it will go on.

Under the light of Singapore’s early evening sun, 16 men are being led out of His Majesty’s Criminal Prison on Outram Road. A crowd of about 6,000 have gathered on Golf Hill, opposite Pearl’s Hill, to watch the unfolding spectacle. Men, women and children representing all the races and faiths of Singapore – Europeans, Eurasians, Malays, Indians, Chinese and Christians, Buddhists, Muslims and freethinkers – are about to participate in an ancient ritual of public justice. Gently sloping heights that had served as the sixth hole of the Sepoy Lines golf links now double up as a viewing gallery. The onlookers have an unobstructed view from a space looking out towards Outram Park, to be levelled and occupied in the near future by the Singapore General Hospital.

Among the spectators is a six-year-old boy named Chan Chon Hoe.1 From his home in Pagoda Street, he had followed the military band of Volunteers that marched up New Bridge Road to Outram Road. Now Chon Hoe peeks out from between the legs and shoulders of the gathered crowd to catch a glimpse of the prisoners. The prisoners are all former sepoys, soldiers of the 5th Native Light Infantry of the British Indian army. Shipped in to defend Singapore, they have now been charged with mutiny in the middle of the First World War. The prisoners’ armed escort are an imposing squad from the Sikh Police Contingent policemen. The tall and burly Sikhs carry Lee Enfield .303 bolt-action rifles that resemble toys in their massive hands.

Heads bowed, the 16 mutineers are ordered to stand to attention by British Army Major E.H. Hawkins of the 4th Shropshire Light Infantry. They obey instinctively, surrounded by two companies of the 4th Shropshires and other British soldiers from the Singapore garrison. Like surplus caddies, British non-commissioned officers and enlisted men hurriedly form three sides of a square with the prison wall. It has become a full-dress show. Colonial officials are sensitive to the spectacle of British power and its salutary effect on the natives. The difference between loyalty and treachery to King and Emperor must be made clear. Imperial officialdom uses the civilising veneer of ceremony and procedure to demonstrate that the Empire’s rule of law trumped the barbaric whims of a debauched Eastern potentate. Never mind the hasty court martial or the macabre theatre that is about to be staged. This Empire had offered the world the Magna Carta. Its ruddy-faced representatives will now serve up an object lesson on the fate of those who ate their salt and then spat it back in their faces.

The prisoners and their escort of Sikh constables are a study in stark contrast. The handcuffed sepoy mutineers wear ill-fitting long kurta shirts, Indian dhoti or Malay sarong. The Sikh lawmen, with their headquarters situated next door in Pearl’s Hill, represent the force of order in these parts. The police sport striped blue and white pagri (turbans) and wear impassive faces behind groomed, raven-dark beards. Their perfectly pressed khaki uniforms are secured by shiny belt buckles while mirror-polished boots under neat puttees reflect glints of the dying sunlight.

Recruited and drilled by their colonial masters, guards and prisoners alike belong to the so-called martial races of India. Both sets trace their origins to the widest reaches of Punjab, Rajputana and the North-west Frontier, well before its violent partitioning between Muslim and non-Muslim in 1947. Hardy specimens hand-picked to perform a lifetime of military labour. Trained to ensure that religion comes a distant second after loyalty to the British Raj. The Sikhs hail from the fertile west of Punjab, while the mutineers are mainly Muslim Rajputs known as Ranghars from small dusty towns in the more backward eastern reaches of Punjab known today as Haryana. These were towns and villages where camels roamed, and home of the sturdy black Murrah buffalo, with the nearest Sikh and Punjabi speakers further up north.

British orientalists and linguists understood these differences. They know that unlike the Ranghars, Sikhs did not wear a cone-shaped kulla hat under their tall pagri. The colonial social engineers of efficient power maintenance shaped and created the martial races and used the age-old caste and class system to their full advantage. Singapore’s Chinese and Malays are largely ignorant of the shades of the sub-continent. These lesser subjects of His Majesty the King deride the darker South Indians as kling, derived from Kalinga, an ancient Indian kingdom, but was derogatorily said to be from the sound of the chains that hobbled them as convict labour. And they label Sikhs, Rajputs and Pathans collectively as Bengalis, because they sailed from the Calcutta port in Bengal to Malaya. Some are confused, having once seen the Ranghars, now bare-headed, wearing turbans, with some even full-whiskered like their Sikh guard.

While some spectators may struggle to discern between the regimented Indians and those in rags, the Sikh police know all the difference between faith and faithlessness. And there is no love lost for the mutineers who had tried to kill some of them in the Central Police Station and even wounded fellow constables. Outram Prison had also come under attack. Now the only remaining link of values between the Sikh police and the sepoy mutineers was a devotion to the code of izzat, or reputation and respect. A question of manly pride, of honour and of shame. Izzat made good soldiers. But if offended it made them vendetta-hunters seeking revenge at any cost. And izzat required them to die like men.

Major Hawkins reads out the court-martial sentences of the prisoners. The 16 prisoners receive sentences with varying lengths of imprisonment. As each verdict is announced, a mutineer is ordered to step forward. Four ex-sepoys of the Taiping-raised Malay States Guides receive the lightest punishment possible – below two years without hard labour. The remaining dozen from the 5th Light Infantry of the British Indian Army are slapped with far harsher penalties. Some face “transportation for 15 years”, or hard labour in a penal colony. Eight of them stare at “transportation for life” in the dreaded Andaman Islands. The Andaman Islands’ Cellular Jail is the Indian Alcatraz. The Indians know it as Kala Pani (Black Water), for it lay across the forbidding waters of the Indian Ocean. Only the fit and those under 40 were sent to the Kala Pani, overseen then by a vicious Irish warden familiar with all the dark secrets of living purgatory. This could mean being shackled like a donkey to a mill, circling in endless loops to grind oil. Or to sit in pitch dark for years with no face or voice apart from your own.

Fates confirmed, the bedraggled group of 16 are marched off back behind the grey prison walls by their police escort. The huge crowd massed behind the cordon of British soldiers has not come all the way just for this. This scene has merely whetted their appetite for the main show that is about to begin.

Spread on and below Golf Hill, 6,000 pairs of eyes follow the final steps of a smaller group of men emerging from the prison gates. A new scene in the theatre of public instruction unfolds. Unlike the 16, the five are handcuffed. And their escorts this time are not the straight-backed Sikh police but white-suited British prison wardens who form a close guard. Affirming British prestige, only the superior race may dispense ultimate justice. The wardens are in no mood to give any quarter, after one of their own was killed outside Outram Prison by the mutineers.

The execution will be carried out in full public view – a spectacle revived after almost 20 years of its prohibition in Singapore. The natives must be taught their manners, including little Chon Hoe. The condemned men are marched to their execution spots with military precision. The weathered and peeling execution wall faces a flat piece of ground on the western side of Outram Road, rising gently to become Golf Hill. An eerie silence holds as the five prisoners are marched in. Quite unusual for a large crowd who is responsible for Singapore’s constant market hubbub. All are captivated now by the sight before them.

Two of the five ragged prisoners had worn officer’s uniforms in the British Indian Army. Dunde Khan is the senior of the pair of cashiered officers. Fat and fair-skinned with a beard and moustache once neatly trimmed, the ex-Viceroy Commissioned Officer had once flashed the two-star epaulette of asubedar (captain) on his shoulder straps. Now ordered to march forward, his muscle memory completes a familiar drill. In step by his side is Chiste Khan, a lean, sharp-faced former jemadar (lieutenant) sporting a long, flowing beard. Garbed in rumpled and soiled civilian clothes, former Subedar Dunde Khan and ex-Jemadar Chiste Khan struggle to retain some soldierly bearing and dignity.

A few weeks earlier, the pair of Khans had been in a very different position. Both were native officers of the 5th Light Infantry garrisoned in Singapore. Dunde commanded B Company of No 1 Double Company and Chiste led D of No 2 Double Company. They had turned out with their battalion for a Monday morning inspection parade by Acting Brigadier-General Dudley Ridout, the General Officer Commanding the Troops in the Straits Settlements. Ridout was conducting his farewell inspection of the regiment just before its redeployment to Hong Kong. The inspection coincided with the Chinese New Year holidays. The festivities had begun the day before. At the stroke of midnight, the settlement’s Chinese population exploded in riotous celebration. Official hours for firing small bombs and crackers were midnight until 1 am and from 5 to 6 am. The large Chinese community in carnival mood could hardly be expected to obey the rules.

In the fast evaporating cool of a humid tropical morning, the paraded sepoys were in no mood to celebrate. And they were eager to break a different set of rules. Many, especially those from the Ranghar half of the dual-race battalion, looked sullen and unhappy. A hard core was ready to explode, itching to do the unthinkable. The Pathans from the other half were in a better state, with several of their own up for the coming promotion test.

Physically, the pudgy-looking Ridout with his bristly toothbrush moustache did not inspire fear or respect. But looks are deceiving. Short and stout, Ridout’s benign and inoffensive appearance was sharpened by cold, piercing blue eyes. He had tried to rally the men with a rousing speech. The Khans and their sepoys listened to his words. Or rather half-heard its translation into Hindustani by their regimental commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Edward Victor Martin. The perennially sleepy-looking Martin was an isolated figure, unpopular with his fellow British officers and judged by some as too sympathetic to the sepoys.

In the rising heat and humidity of the morning, Ridout’s speech rehearsed a tired formula: “The empire is vast and the duties of guarding it are great”2 – words meant for the British Tommy, not Jack Sepoy. Describing his burden of command as General Officer Commanding the Straits Settlements was the last thing the already troubled, confused and demoralised sepoys needed to hear. Later that day, Lance-Naik (Lance-Corporal) Najaf Khan wrote a letter to his brother in India lamenting:

“As this war is such that no one has returned out of those who have gone to the war. All died. And those who have enlisted will not live alive. Believe this. World has died. No one has escaped who has gone to the war. All have perished. And there is recruiting open, don’t let any men enlist. As all are being taken to the war. All will be caused to be killed.”3

With a battalion and their own minds in disarray, some of the sepoys developed their own conspiracy theories, with help perhaps from passing agents of influence. Their once-disciplined heads held many confusing ideas. Some noble, others dangerous and mixed with trivial feuds and simmering frustrations. They were being sent away from Singapore to fight and kill Turks – their fellow Muslims. This contradicted the one true faith. Even worse, they speculated that their ship was to be sunk en route to their next post. Reflecting the Rajput Hindu origins of his Ranghar identity in a moment of great stress, Sepoy Shaikh Mohammed wrote to his family, reflecting Hindu ideas of resurrection:

“It is with sighing, crying, grief and sorrow to tell you that the transfer of the regiment on the 20th February is now a settled fact. It will go to Hong Kong. But don’t know this, whether it is going to the war.

“God knows what kinds of trouble we will have to confront. What is this war? It is resurrection. That who goes there, there is no hope of his returning. It is God’s punishment. If God released us from this calamity we will take to have reborn. We are very much confused and shocked. All the regiment is in sorrow together.”4

On their part, the pair of ex-officer Khans, now standing with their backs against the walls of Outram Prison, had done their own listening, thinking, and whispering. Quiet intriguing was soon followed by bold declarations and preaching. As Viceroy Commissioned Officers, men like the Khans were expected to know better than to encourage such seditious talk. They sat at the top of the pyramid of Indian military labour that was recruited to defend the British Empire. Raised from the ranks of the sepoys for good service, they were trained not to question why but to do or die.

Fat Dunde certainly didn’t look the part of a recruiting station officer. But he appeared to have something to prove. Displaying a maverick streak, he wore non-regulation earrings, a Rajput custom to project warrior virility. Dunde also had unusual interests for a professional soldier and an officer at that. In Singapore he had taken personal music lessons from a musician from his village of Bajpur in Gurgaon. Dunde was fond of playing his newfound instrument and singing to his men, an officer doubling up as an entertainer from home. Located in the far east of then undivided Punjab, the district of Gurgaon was mid-way between Delhi and the sacred city of Mathura. It was not far from the place of legend, where the Hindu god Krishna was supposed to have sported with the cowherds’ maidens on the banks of the river Yamuna. The people of Gurgaon were fond of song, poetry and the edible cannabis known as bhang. They were the original hippies of India.

In Singapore, Dunde also found other attractions. With Chiste, he enjoyed the company of a wealthy and sociable Singapore merchant named Kassim Ismail Mansoor. A Gujarati Muslim from Bombay, Kassim was a Walter Mittyish character who dabbled in sedition. The 65-year-old jihadi socialite opened his weekend bungalow on Pasir Panjang Road to the officers and their sepoys.

Chiste was a disciple of the enigmatic Nur Alam Sham. A mysterious Muslim preacher and Sufi Master (pir), the latter had a cult following among Indian and Malay Muslims in Singapore. Nur Alam Shah delivered sulphurous sermons at his mosque on Kampong Java Road, just down the road from the house where Singapore’s first Prime Minister, Lee Kuan Yew, would be born a few years later.

As the First World War turned into a brutal conflict of attrition, Nur Alam Shah had raised thorny questions for the sepoys to consider. To whom was loyalty owed? To which Kaiser and to which Emperor? Charismatic Chiste also had a way with words. He persuaded some of his men that the tide was turning against British rule. Largely illiterate and unschooled, the thoughts of the sepoys did not match the precision or logic of trained minds. This thinking was dangerously open-ended and tumbled through their heads like the fake news Lance-Naik Fateh Mohammed had shared with his father on the day the mutiny broke out:

“The war increases day by day. The Germans have become Mohammedans. Haji Mahmood William Kaiser… [whose] daughter has married the heir to the Turkish throne… to succeed after the Sultan. Many of the German subjects and army have embraced Mohammedanism. Please God that the religion of the Germans (Mohammedanism) may be promoted or raised on high.”5

All it took was a spark, which eventually ignited. An explosion of gunfire amid the noise and smoke of Chinese New Year firecrackers and bomblets. A cluster of little rebellions had erupted within the regiment. Soon the sepoys had the run of the island. Chaos. Confusion. And then the inevitable betrayal.

Secret agents in their midst. The prisoners they had sprung who went their own way. The rounding up. Wounded and bloodied after his capture, Chiste was heard reciting the Qur’an. Its familiarsurahs both balm and support. The trials. The cover-up. Documents sealed away for half a century or more in dusty archives, eaten by termites or firebombed or misplaced.

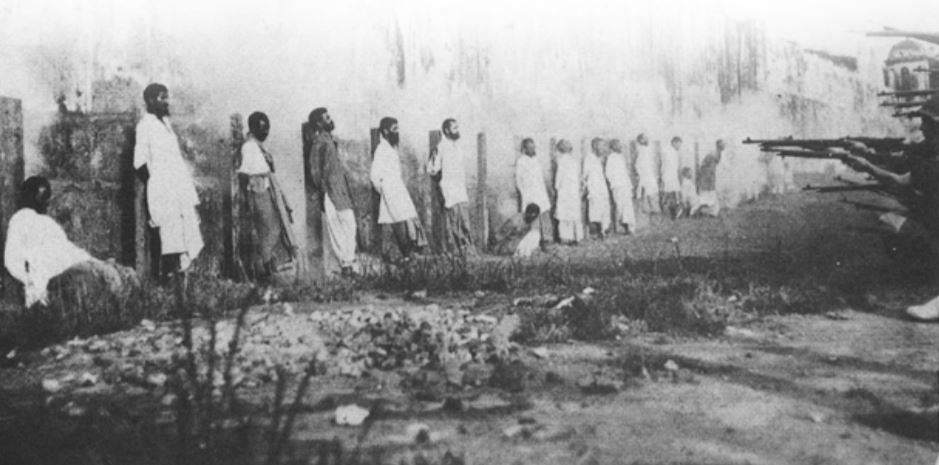

Turn back now to the scene outside the Outram Road Criminal Prison in 1915. A moss-splotched grey wall and three lines of khaki-clad soldiers forming a square on the green turf. A red, laterite road separates the spectators from the spectacle. The little six-year-old boy staring wide-eyed. The Khans with three others. About to face their earthly fate in a few moments. They are not being sent back to the Kala Pani, the dreaded black sea they had crossed to reach Singapore, but to a blackness of another kind – sakrat-ul-maut – senselessness. And not before jan-kandani – the agonised sucking out of life.

One choice remains for the proud Ranghars – they must uphold the Rajput warrior tradition. Dunde Khan son of Khan Mohammed Khan, Chiste Khan son of Mussalam Khan, two havildars (sergeants) and a sepoy (private) next to them hold their heads up and look straight ahead. They see heavy wooden posts sticking out of the ground like dead men standing. But their izzat of manly honour requires them to remain as steady and as erect as those poles.

Khaki-clad army officers scurry about in the square making final preparations. They are joined by a gaggle of civilian officials and warders. The civilians are in pristine white cotton drill suits with matching solar pith helmets on pomaded heads. To the spectators atop Golf Hill, the harried officials down below resemble brown and white ants in frenzied activity. The bureaucrats of Empire dash around fussing right up to the moment the five condemned men are marched to their execution spots.

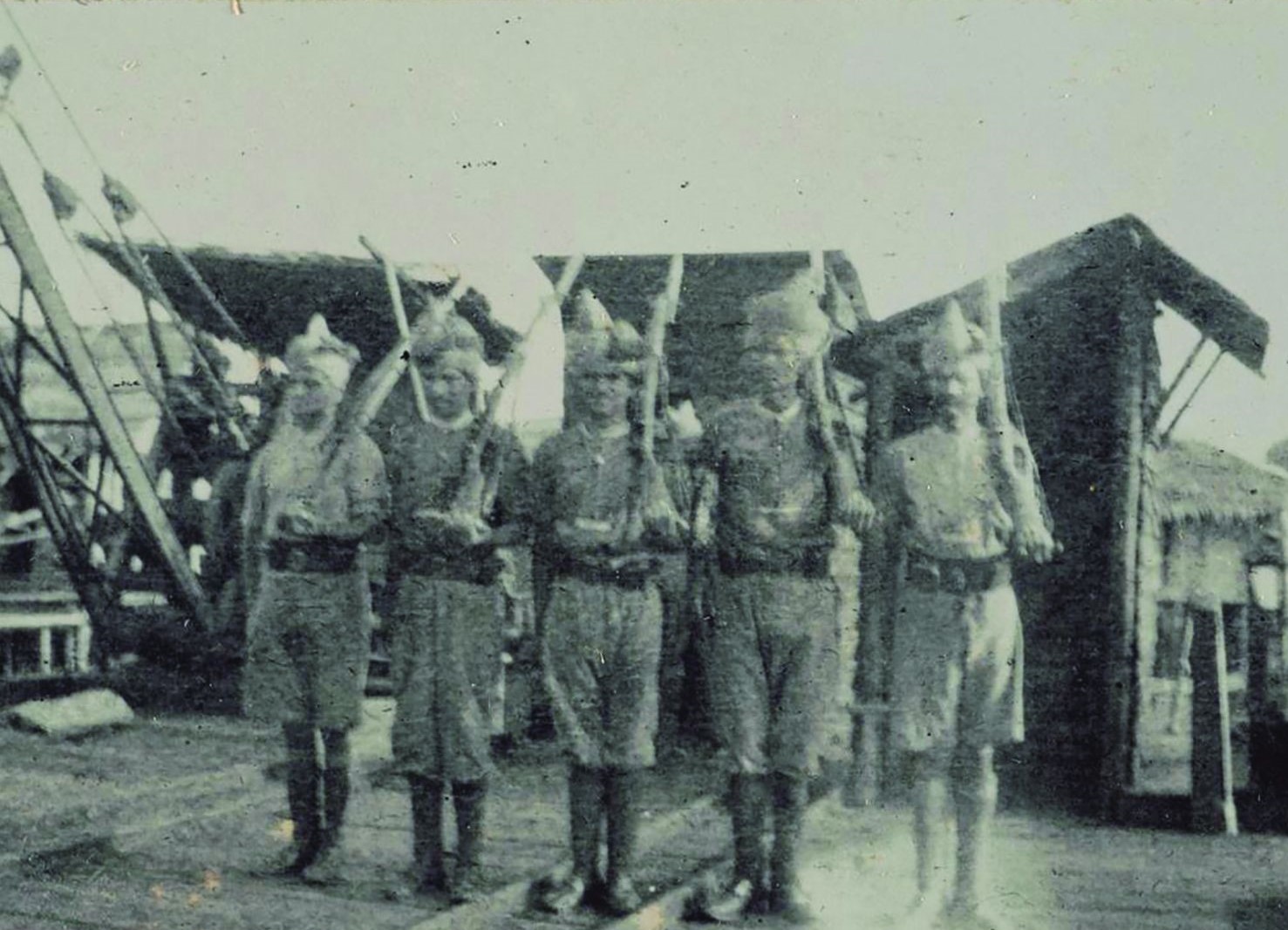

The firing squad is composed of 25 men from the Royal Garrison Artillery under the command of Second Lieutenant Frank Vyner. Wearing large khaki pith helmets, with their knobbly, white knees peeking out between pulled up socks and “Bombay bloomers” shorts, the firing squad resembles overgrown schoolboys. In fact, they are artillerymen who have exchanged their large-bore guns for rifles.

With little fanfare, the doomed men are strapped to the five-foot timber stakes that throw long, ghostly shadows on the prison’s high outer perimeter wall. Their naked brown ankles are secured firmly by cotton thongs. The final whispered murmurings of the large crowd are hushed. Major Hawkins steps forward. He reads out a statement in a firm and loud voice:

“These five men, Subedar Dunde Khan, Jemadar Chiste Khan, 1890 Havildar Rahmat Ali, 2311 Sepoy Hakim Ali and 2184 Havildar Abdul Ghani have been found guilty of stirring up and joining a mutiny and are sentenced to death by being shot to death… All these men of the Indian Army have broken their oath as soldiers of His Majesty the King. Thus justice is done.”6

It was a century-old map of Singapore discovered in a London bookshop about 10 years ago that launched my quest. The topographical map showed intriguing features of a settlement in Singapore and its infrastructure, formed between now-levelled hills and drained swamps, with a port that was already the world’s seventh busiest in 1914. I was intrigued by a prominently marked German prisoners camp, setting me off on a journey to find the “lost treasure” of Singapore’s neglected history just before, during and after the First World War.

Umej Bhatia’s Our Name is Mutiny: The Global Revolt Against the Raj and the Hidden History of the Singapore Mutiny, 1907–1915 retails at major bookshops and is also available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries (Call nos.: RSING 959.5703 BHA-[HIS] and SING 959.5703 BHA).

Umej Bhatia’s Our Name is Mutiny: The Global Revolt Against the Raj and the Hidden History of the Singapore Mutiny, 1907–1915 retails at major bookshops and is also available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries (Call nos.: RSING 959.5703 BHA-[HIS] and SING 959.5703 BHA).

The result is my book, Our Name is Mutiny: The Global Revolt against the Raj and the Hidden History of the Singapore Mutiny, 1907–1915, which focuses on an event usually known as the Sepoy Mutiny of 1915. The sepoys were Indian soldiers who turned against their British officers and marauded through Singapore on the eve of their departure for Hong Kong. The account in my book differs from the conventional historical narrative in that I uncover and tease out the globetrotting ideas and the rolling-stone revolutionaries chased by imperial policemen who played their part in influencing, seducing and subverting the sepoys to mutiny. Crucially, the mutiny was not just a local affair but a revolt and insurgency with a global flavour, one of a number of planned uprisings under the banner of a wider Mutiny movement.

The uprising of sepoys in Singapore was a symptom of an overstretched and slowly declining British Empire, set during the period of the First World War, with its unique cocktail of jihad, or holy war propaganda, promoted by the Germans and Ottoman Turks, and ideas of the Ghadar or Mutiny movement, pushed by Indian revolutionaries from across the Atlantic Ocean. These ideas crossed the Pacific to port cities like Hong Kong, Rangoon, Singapore and Penang, and over the Indian Ocean to British India.

The Ghadar or Mutiny movement part of the story that I tell had its roots not only in northern India, but also, and more importantly, among the Punjabi immigrants in the US and Canada. It brought them together with Bengalis who had been leading an underground movement against the British for some time. An idea of national identity was developing among these revolutionaries without them being fully aware of it. I found it especially interesting that religious and even regional identities were so fluid, and concepts of race, nationhood and even religious identification were in a plastic phase of definition. That phase is much less plastic now, while the use of identity politics by the British Empire as a form of imperial control has had lasting repercussions.

The Singapore mutiny of 1915 provided the canvas to sketch out a broader story of war, migration, populism, terrorism, fake news and revolution in an earlier era of globalisation. So many echoes of the present can be found in the past. I wanted to use a little-known event in a period that most historians of Singapore and the region seem to overlook, to make this point.

With this book, I hope to show that the history of Singapore, and even its present and certainly its future, is driven by its location and its positionality as a global city. Our understanding of Singapore is enriched by interpreting events and episodes of its history by carefully tracing the contours of its global links and connections, with all the opportunities, challenges and threats that come with this globalism. And telling that story creatively while staying true to the facts with the demanding but rewarding long form of narrative non-fiction is all part of a universal story of what happens when the unstoppable force of revolt meets the immovable object of power.

Umej Bhatia is the author of Our Name is Mutiny: The Global Revolt Against the Raj and the Hidden History of the Singapore Mutiny, 1907–1915 (2019). He is a career diplomat from Singapore and is currently based there. His first book is on Muslim memories of the Crusades.

Umej Bhatia is the author of Our Name is Mutiny: The Global Revolt Against the Raj and the Hidden History of the Singapore Mutiny, 1907–1915 (2019). He is a career diplomat from Singapore and is currently based there. His first book is on Muslim memories of the Crusades.

Notes

-

Rajagopalan, M. (2000, April 13). Man, 91, scarred by sepoy execution. The Straits Times, p. 35. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Sareen, T.R. (1995). Secret documents on Singapore mutiny, 1915 (p. 717). New Delhi: Mounto. (Call no.: RSING 940.41354 SAR-[WAR]) ↩