The Vietnam War Through Singaporean Eyes

Four journalists from Singapore covered the Vietnam War for the international news media. Only one survived. Shirlene Noordin has the story.

Some of the most iconic and impactful images of the 20th century emerged from the Vietnam War, or Second Indochina War, which took place from 1955 to 1975.

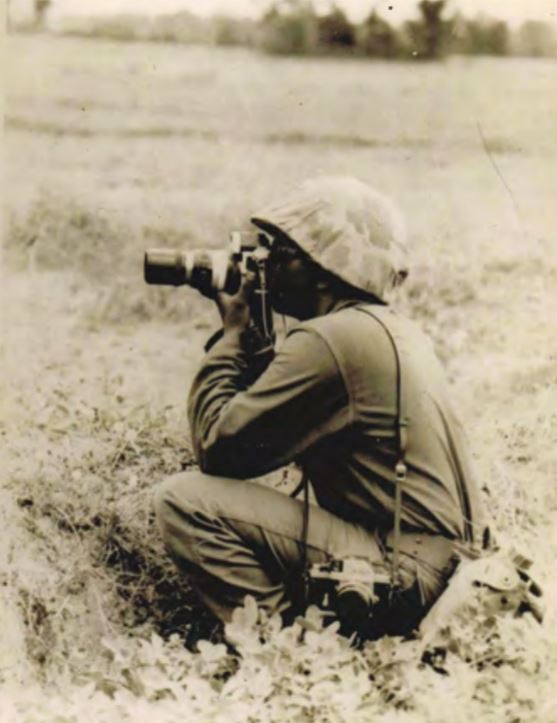

During what the Vietnamese called the Resistance War Against America, the world’s media had unprecedented access to the combat zone as these photographers followed American troops into battle. By 1968, at the height of the war, there were about 600 accredited journalists in Vietnam.1 Photographers, camera crew and war correspondents could easily hitch a ride in a helicopter and find themselves in the thick of combat action. The media had unfettered access to the events as they unfolded, with the photographers and cameramen obtaining some of the most vivid, uncensored images and video footage of war ever captured.

As a result, for the first time, images of the war were beamed directly into the homes of Americans and people around the world through television, and also appeared in newspapers and magazines. As Vietnam is more than 13,000 km away from the US, these images helped provide new perspectives and shape the understanding of a conflict that, as a result of the draft – as conscription was known2 – directly affected a large swathe of American society.

Many of the journalists covering the conflict were American. However, because it was such a significant event, journalists from all over the world descended on Saigon to document the war, including those from Asia.

Among the Asian journalists were at least four Singaporeans – Chin Kah Chong, Sam Kai Faye, Terence “Terry” Khoo and Chellapah “Charlie” Canagaratnam. Sadly, of the four, only Chin survived.

Chin Kah Chong

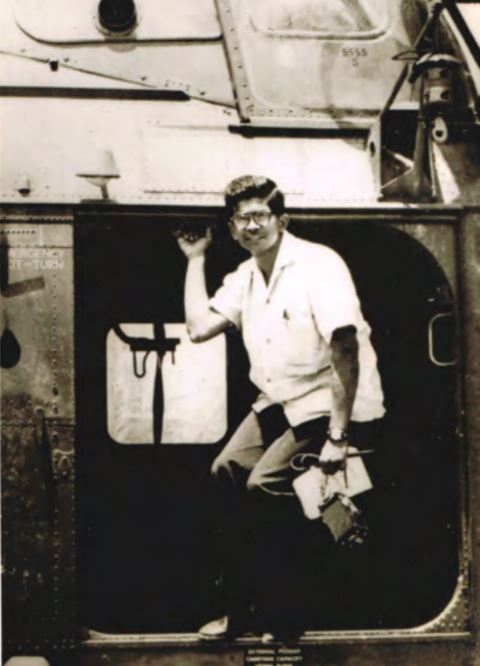

Born in Singapore in 1931, Chin Kah Chong began writing for several news outlets from the early 1950s. He started out as an intern for the Chinese newspaper Chung Shing Jit Poh and a number of other Chinese papers, and also did a three-month stint in Kuala Lumpur.

When Chin set foot in Saigon in 1954, it was by accident rather than design. He was not in the city to cover the ongoing First Indochina War3(1945–54). By chance, his Hong Kong-bound plane had to be diverted to Saigon airport due to engine trouble. This was two weeks before the French defeat on 7 May 1954 at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu fought against Viet Minh forces.4 The scene that greeted him on the tarmac was of wounded French soldiers waiting to be evacuated.5 This was his first brush with the Indochina Wars.

When Chin was covering the Bandung Conference in April 1955, he met Hawaii-born and Hong Kong-based journalist Norman Soong, who had founded the Pan Asian News Agency (PANA) as an independent international news agency “of Asians, by Asians, for Asians”.6 Chin was offered the job to manage and write for the agency’s Chinese-language news service based in Singapore.

One of Chin’s first major assignments for PANA was the Baling Talks on 28 December 1955, which brought together Tunku Abdul Rahman, Chief Minister of the Federation of Malaya; David Marshall, Chief Minister of Singapore; and Chin Peng, leader of the Malayan Communist Party, to discuss amnesty. In 1956, PANA sent him to Saigon for five months to cover the unifying national elections that had been established by the Geneva Accords of 1954.7 Thus began his two-decade-long coverage of the Vietnam War, shuttling between Singapore and Saigon.

The elections never took place because it was cancelled by South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem. However, in 1956, Chin managed to score an exclusive interview with Tran Le Xuan, popularly known as Madame Nhu. She was the wife of the president’s younger brother Ngo Dinh Nhu, who was also the president’s chief political adviser. As President Diem was not married, Madame Nhu assumed the duties of the first lady.

Chin recounted in his 2011 memoir, 越南,我在现场:一个战地记者的回忆 (Vietnam, I Was There: A War Correspondent’s Stories), that it was during the interview when he came up with the title “First Lady”, which was later widely used by the Western press. Madame Nhu was extremely pleased as she hated the nickname “Mother Tigress” which the American correspondents had given her.8

As a committed journalist covering a war, Chin went on risky missions to get to the heart of a story.

In 1961, Chin was one of three journalists – the other two were from Russian newspaper Pravda and The New York Times – invited by Norodom Sihanouk, then Cambodia’s head of state, to visit the Cambodia-Vietnam border to dispel accusations from the South Vietnamese government against him for sheltering Viet Cong fighters in Cambodia. At the time, Cambodia had closed its doors to Western journalists.9

In April 1965, Chin and his Japanese photographer colleague H. Okamura ventured into the Iron Triangle, an area northwest of Saigon that had become a major stronghold of the Viet Cong. It was also where the final attack on Saigon was orchestrated in 1975. They were accompanied by a female Viet Cong liaison officer for a meeting with Viet Cong fighters. After a four-hour bus ride northwest of Saigon, they arrived at an abandoned rubber plantation. They were met by a five-year-old boy who led them to the village of Bau Bong. There, they were briefed by a Viet Cong cadre who told them that the village had been heavily bombed by US air force planes just a few days before.

When the Vietnam War ended, Chin continued running PANA’s Chinese-language news service from Singapore until his retirement in 2004. He has written several books, one of which, 我所知道的李光耀 (LKY Whom I Knew),10 won the Singapore Literature Prize in the Chinese non-fiction category in 2016. Though now in his 80s, Chin continues to write and is currently working on his next book.

Terence “Terry” Khoo and Sam Kai Faye

It was Chin who spurred two fellow Singaporean journalists – Terence (better known as Terry) Khoo and Sam Kai Faye, former photographers with The Straits Times, to venture to Vietnam. Both Khoo and Sam covered the war for about a decade, between 1962 and 1972.

Born in 1924 in Penang, Sam came to Singapore to work for The Straits Times from 1950 to 1955, where he was an award-winning photographer. In 1954, he became the first Asian to win the Best News Picture in the British Press Pictures of the Year Competition for his photo of a plane crash at Kallang Airport. 11 He also won the British Commonwealth Photo Contest in 1958 and 1959.

After leaving the newspaper, Sam struck out on his own as a freelance photographer and shared office space with PANA, where Chin was the bureau chief. As PANA did not have its own staff photographers, it frequently used Sam for assignments.

Khoo, who worked at The Straits Times from 1954 to 1956, was 12 years younger than Sam. But despite the age difference, they became best friends with Sam taking Khoo under his wing in the newsroom. Khoo would often visit Sam at the PANA office; soon, Khoo began taking on assignments for the agency.

Chin, Khoo and Sam became fast friends, and Chin often took the other two on assignments in Singapore and Malaya in the mid-1950s. The three of them covered the Malayan Emergency during the latter part of the 1950s as well as the Duke of Edinburgh’s visit to Sarawak in 1959.

In 1960, Chin arranged their first trip to Vietnam. A Royal Air Force (RAF) plane was scheduled to fly Singapore-based journalists to Saigon to cover a story about an RAF-led relief mission for flood victims. Chin managed to get both Sam and Khoo on the same flight as him. While there, Sam and Khoo were so enamoured of the city that they missed their flight home and a special flight had to be arranged for them the next day.12

In late 1962, Khoo moved to Saigon to work, while Sam did so much later. Chin related that Khoo was able to make the move earlier because he was single, while Sam, although unmarried, was running a photography business with his elder brother, Sam Kai Yee, who was also a Straits Times photographer.13

In Saigon, Khoo worked initially as a freelancer and counted among his mentors David Halberstam of The New York Times and Neil Sheehan of United Press International, both Pulitzer Prize winners, as well as Malcolm Brown of the Associated Press and the prominent historian and war correspondent, Bernard B. Fall.14 Khoo also did some work for Asia Magazine, a widely circulated weekly publication focusing on topics in Asia.

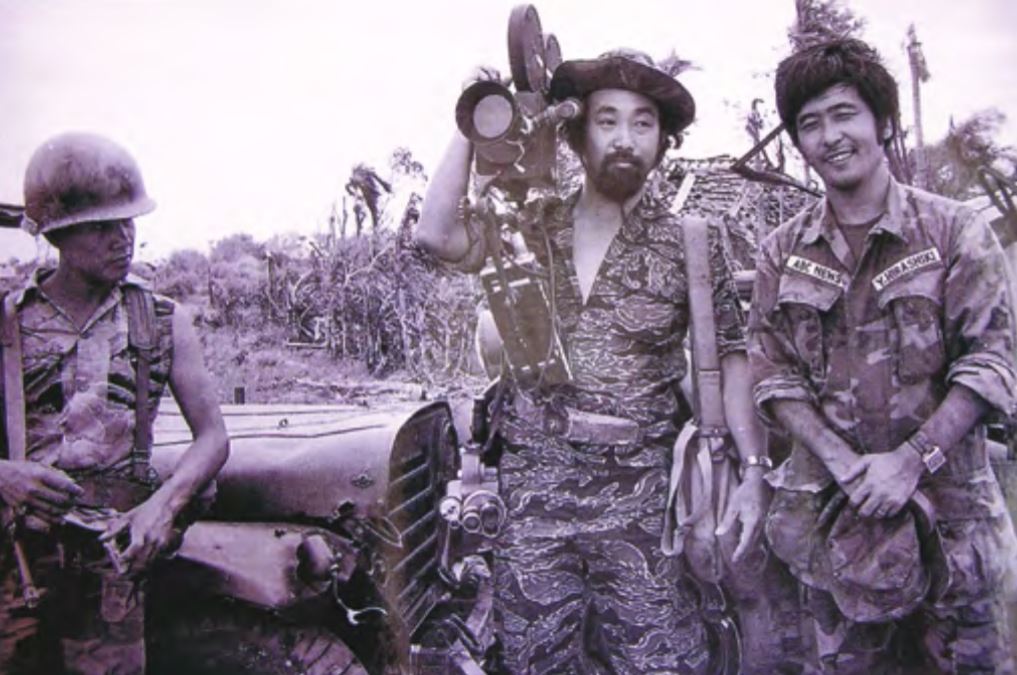

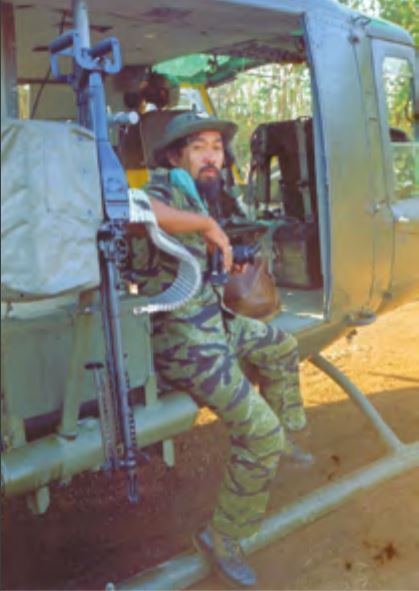

Before long, Khoo was hired by ABC News as a cameraman where he became much sought after for not only his keen eye, but also his language skills and personable nature. Apart from speaking English, Malay and several Chinese dialects, Khoo picked up French and Vietnamese, thus making him indispensable to his American colleagues. The ability to speak the local language also endeared him to the Vietnamese with whom he worked.

Among the Asian journalists, Khoo was looked upon as a leader and mentor, especially to many of the younger, inexperienced journalists in Saigon. He welcomed them at his house, which was fondly referred to as “Terry’s Villa”, and provided them with food. He even lent money whenever someone was in need.15

Khoo’s ability to remain cool and calm under pressure also earned him great respect among his peers. In Cambodia, where the situation was far more unpredictable and dangerous, Khoo and his ABC News colleagues – American correspondent Steve Bell and Japanese soundman Takayuki Senzaki – were once captured by an insurgent patrol and held for several hours in an area several kilometres outside of Phnom Penh. Khoo managed to talk his way out of the situation and even offered himself up as hostage when the insurgents wanted to hold Steve Bell. Luckily for everyone, the leader changed his mind and let them all go free.

An incident in early June 1972 in the besieged town of An Loc, in southeastern Vietnam, demonstrated the kind of person Khoo was. When Khoo and ABC News correspondent Howard Tuckner arrived in An Loc, they found it littered with dead bodies as well as numerous wounded American soldiers waiting to be evacuated by helicopter.

After completing their assignment, Khoo and Tuckner were supposed to return by helicopter to Saigon that same day. However, instead of boarding the only helicopter of the day, the two men elected to give up their seats to severely wounded soldiers in need of urgent medical attention.

Staying an unplanned night in An Loc could have cost them their lives and their exclusive report but they made the decision to stay. For his bravery, skill and generous spirit, Khoo was dubbed “The Dean of the Vietnam Cameramen”.

Sam Kai Faye, who had left for Saigon in the late 1960s, started as a freelance cameraman for ABC News, but soon became a permanent member of the team. Sam Yoke Tatt, Sam Kai Faye’s only nephew, remembers his uncle as a calm, mild-mannered man with an adventurous streak. It was this sense of adventure that drew him to cover the Vietnam War, despite the obvious dangers.

From 1959 until the time he left for Vietnam, Sam and his brother Kai Yee ran a photography business in Singapore called Sam Brothers Photographers, doing commercial, event and editorial photography work. According to Sam Yoke Tatt, Khoo, who had already established himself in Saigon, persuaded Sam Kai Faye to leave Singapore to join him at ABC News as a cameraman, although Sam was more of a stills photographer. Once in Vietnam, Khoo helped Sam familiarise himself with the film camera, which Sam quickly mastered.16

Among the many assignments that Sam took on for ABC News was one on a B-52 bombing mission over North Vietnam. His nephew, Yoke Tatt, said that Sam had received a certificate from the American military when the mission was completed.17

Both Khoo and Sam were described by Kevin Delany, ABC News bureau chief, as “tough and courageous Singapore Chinese who had produced years of combat footage”.18

It’s All Fate Anyway…

In late 1971, Chin met with Khoo and Sam in Saigon for what would be the last time all three would be together. Chin was with Sam in his hotel room, chatting about the situation in Vietnam and the future. Khoo had not arrived as he was delayed by the curfew, which took place regularly after dark in Saigon.19

Chin remembered Sam saying that he was feeling more and more afraid of the situation. The Viet Cong forces were becoming better armed, and the fighting was getting more intense. Sam told Chin that he wanted to call it a day and return to Singapore.

Khoo joined them after midnight and, like Sam, also felt that it was time to leave. That night, the three Singaporeans talked about their future into the wee hours of the morning.

Yasutsune “Tony” Hirashiki, a renowned ABC News cameraman and Khoo’s best friend in Vietnam, wrote in his memoir, On the Frontlines of the Television War: A Legendary War Cameraman in Vietnam, about Khoo’s growing anxiety over their safety in Vietnam. Khoo told Hirashiki that he had accepted a transfer to ABC’s bureau in Bonn, Germany. The Singaporean had become engaged to Winnie Ng, a secretary in ABC’s Hong Kong office, and he was looking forward to getting married and starting a new life with her.

Some time in mid-July 1972, Khoo returned to Saigon after a vacation in Hong Kong and was supposed to remain there in preparation for his imminent departure to Bonn. Instead of remaining in Saigon, Khoo told his bureau chief Kevin Delany that he needed a few more photographs for an unfinished feature story and left for Hue on 15 July.

On 18 July, Korean cameraman In Jip Choi was supposed to relieve Khoo in Hue. As Choi was nursing a nasty cold, Delany asked Sam to go in Choi’s place. The plan was for Choi to take over from Sam once he was feeling better. Together with newly minted news correspondent Arnie Collins, Sam arrived in Hue on 20 July to replace the crew consisting of Khoo, Korean soundman T.H. Lee and veteran American correspondent Jim Bennett.

In Hue, Khoo heard a rumour that a North Vietnamese tank had been spotted west of Highway One, between Hue and Quang Tri City, located south of the demilitarised zone. Quang Tri was the site of the bloody Easter Offensive of 1972 during which the North Vietnamese an effort to gain territory. The fighting began on 31 March and continued until 22 October that year.

Never one to miss a story, Khoo insisted on checking out the situation although having completed his last assignment, he was supposed to be on his way back to Saigon. On 20 July, Khoo, Sam, T.H. Lee and South Vietnamese Army photographer Tran Van Nghia headed to an open field near Highway One where fighting was reported to have occurred.

Moving into the deceptively quiet field with their heavy camera equipment, the men were suddenly caught by sniper fire, which hit Sam. Everyone quickly dived for cover. Lee asked Khoo, “Are you all right?” to which Khoo replied, “I’m ok but Sam has been hit.”20

When a second attack happened, Lee heard Khoo moaning in pain. Tran was also injured but Lee, who was trained in martial arts, managed to roll along the ground until he reached the edge of the field near the road and escape to safety.

The heavy fighting continued with Khoo, Sam and Tran caught in the crossfire. A US reconnaissance plane later saw Khoo and Sam lying motionless, side by side on the ground, but could not confirm if they were dead or alive. After three days of heavy shooting, their bodies were finally retrieved. Hirashiki and Delany had to identify the bodies.21

In 2006, Delany wrote, “It was clearly the low point of my stay in Vietnam. Heavy fighting had continued in the area of ambush for three days after they went down, and by the time another cameraman and I were able to travel to the scene, we had trouble identifying their remains.”22

According to Chin, the hospital in Saigon had instructed that the coffins remained closed during Khoo’s and Sam’s funeral service in Singapore.

Following the deaths of his two good friends, Chin recalled that Khoo had once said, “When I die, I’ll surely go to heaven, because I’ve already been to hell,” a reference to his experiences during the war. ABC News correspondent Arnie Collins, who was with Khoo and Sam before they left on their fateful assignment, recounted Khoo’s last words after warnings for them to be careful: “It’s all fate anyway, baby, so play it cool.”23

In memory of both men, ABC News set up a two-year fellowship in the name of Terence Khoo and Sam Kai Faye for Asian students studying at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism. Khoo also bequeathed a third of his insurance money of $62,500 to the University of Singapore (now National University of Singapore). Yearly awards of $1,300 were given to medical students from low-income families.

Chellapah “Charlie” Canagaratnam

The fourth Singaporean journalist in Vietnam was Chellapah Canagaratnam, nicknamed Charlie or Charles Chellapah by the Americans. He was born in Singapore in 1940, the fourth child in a family of 10.24

Chellapah arrived in Saigon in January 1965.25 Although Chin, Khoo and Sam were in South Vietnam at around the same time that Chellapah was there, there is no evidence that the trio met Chellapah in Saigon or that they were even acquainted with him.

Chellapah had been a sports reporter with The Singapore Free Press, covering mostly soccer matches before becoming a freelance photographer. He then moved to Kuala Lumpur where he worked for The Malayan Times and subsequently to Sabah for the Sabah Daily Express.26

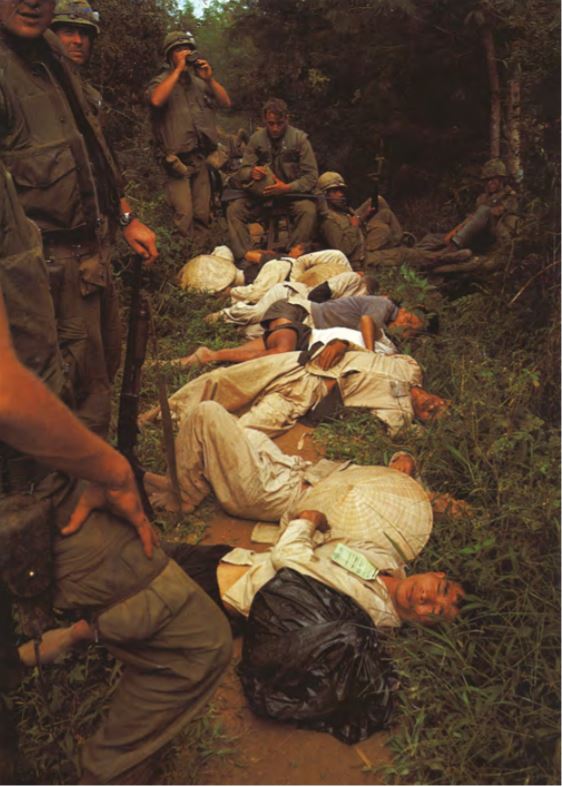

An avid sportsman, Chellapah raced both cars and motorcycles, and participated in local Grand Prix races. Still a bachelor, his thirst for adventure, his free spirit and sense of purpose brought him to Vietnam where he worked as a freelance photographer for Associated Press. Chellapah’s close-up shots of casualties and combat were so dramatic that he was warned by Horst Faas, his Associated Press photo editor, to be careful.27

On 14 February 1966, Chellapah was in Cu Chi, northwest of Saigon, where he had accompanied some American soldiers on a road-clearing mission. Cu Chi was also known as Hell’s Half Acre because of the sheer number of people killed by camouflaged Viet Cong snipers in the dense jungle, under which was a complex network of connecting tunnels used by the Viet Cong.28

During the mission, a Viet Cong mine was set off. As Chellapah scrambled towards those wounded, a second mine exploded, instantly killing everyone. His family only learned of his death later from the BBC World Service.29

Chellapah was the third Associated Press photographer to die in Vietnam in less than a year, and Horst Faas had to report the circumstances of his death to the president of the company. According to Faas, Chellapah’s last roll of film showed how he was in the thick of the action.

He said, “Here are the last pictures by photographer Charlie Chellapah… This last roll of film was released by the authorities today along with his other personal effects. The pictures reveal, better than any words could, how close Chellapah was to the action up to the moment of his death.”30 The last photograph taken by him shows an American soldier holding a seriously wounded comrade.31

Associated Press made arrangements for Chellapah’s body to be flown back to Singapore. He was cremated and his ashes scattered in the sea off Bedok.32

Chellapah’s elder brother and his sister recounted that one month after his funeral, they received a letter Chellapah had written before he died, informing them that he was planning to go to Hong Kong and at the same time purchase insurance coverage for himself. Sadly, this did not happen.33 According to Chellaph’s brother C. Tharmalingam, “Chellapah was a selfless person who always put others before himself, whether it was his school mates, colleagues or comrades. It was this commitment to work and friendship which claimed his life. Unfortunately, his courage was his misfortune.”34

Leaving a Legacy

These Singaporean journalists went to Vietnam with a sense of purpose and devotion to duty: to bring stories of the war and the people involved in it to the world. The photographs taken by Sam Kai Faye, Terence Khoo and Chellapah “Charlie” Canagaratnam were published in international newspapers and magazines, and the footage they shot appeared nightly on the news on American television. Whether they were aware or not, their perspectives of the war as seen through their work contributed to the international public discourse about Vietnam at the time. As the bureau chief of PANA, the stories that Chin Kah Chong wrote and the books he published offer an Asian perspective on this prolonged war in Southeast Asia.

The news stories that these men chased came at a great personal cost. Three of them paid with their lives. Chellapah, in wanting to help the wounded, met his fate, cutting short the life of an exceptional young journalist who had a bright future ahead of him. Sam and Khoo died as they had lived – as best friends committed to each other and wanting to help each other out. Chin survived the war but lost two close friends.

Their consummate professionalism, their selfless courage, and their unstinting generosity of spirit continue to be an inspiration to journalists all over the world.

The First Indochina War (1945–54), or what the Vietnamese called the Anti-French Resistance War, came on the back of World War II in Asia. The returning French colonial forces were pitted against the nationalists led by Ho Chi Minh and Vo Nguyen Giap, united under the banner of the Viet Minh fighting for Vietnamese independence.

Fearing a communist victory, the United States officially provided military assistance to the French in 1950 and laid the groundwork for the subsequent protracted American involvement in Indochina.

The Viet Minh forces were, in turn, supported by China and the Soviet Union. What started as a low-level insurgency escalated into conventional war, which raged on until the Battle of Dien Bien Phu that lasted from 13 March to 7 May 1954 and saw the defeat of France.

In July 1954, the Geneva Agreements were signed. As part of the agreement, the French agreed to withdraw their troops from North Vietnam, leaving the Viet Minh in control.

South Vietnam came under the control of Ngo Dinh Diem, who was first the prime minister and then became president in 1955.

Vietnam temporarily became a divided country at the 17th parallel, pending elections within two years to choose a president and reunite the country.

As the French withdrew, the First Indochina War segued into the Second Indochina War (1955–75), also known as the Vietnam War. Officially, it was a war waged between the communist North Vietnamese Army and its allies, the Viet Cong, and the South Vietnamese government backed by the United States.

By 1961, the American military effort had intensified and in 1965, the first combat units from the United States landed in South Vietnam, marking a turning point in the war.

American public support for the war soon declined because of the prolonged nature of the conflict and the large number of American casualties in a war that was taking place overseas. Media reports, news photographs and video footages also helped fan resistance to the war.

In 1970, America began withdrawing its troops from Vietnam with the last batch of soldiers leaving in 1973. The North Vietnamese Army continued its push into South Vietnam after the American withdrawal. With the US Congress cutting military aid to South Vietnam, the weakened South soon proved unable to hold back the North. On 30 April 1975, Saigon fell to the North Vietnamese Army. According to estimates, about three million Vietnamese civilians and combatants died during the conflict while close to 60,000 Americans were killed or missing in action.

The war in Vietnam soon spilled over into neighbouring Cambodia and Laos, resulting in the Third Indochina War (1975–91) which involved Thailand and China. In 1975, armed conflicts between Vietnam and Cambodia resulted in the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia in 1978 that eventually led to the fall of the Khmer Rouge government in Phnom Penh. The remaining Khmer Rouge forces retreated to the Thai-Cambodian border. In the following decade, Thai and Vietnamese troops clashed on several occasions.

China had objected to the invasion of Cambodia and launched attacks on Vietnam’s northern provinces in February 1979, capturing several cities near the border. Although China withdrew from Vietnam in March 1979, both countries were engaged in border disputes and clashes until 1990.’ The 1991 Paris Peace Agreements officially marked the end of the war between Vietnam and Cambodia.

Shirlene Noordin is a communications consultant specialising in arts and culture. In 2011, she organised the exhibition “Requiem - By the photographers Who Died In Vietnam and Indochina” with NAFA Galleries. In March 2019, she curated the exhibition “Battlefield Lens: Photographers of Indochina Wars 1950–1975” held at the Selegie Arts Centre.

Shirlene Noordin is a communications consultant specialising in arts and culture. In 2011, she organised the exhibition “Requiem - By the photographers Who Died In Vietnam and Indochina” with NAFA Galleries. In March 2019, she curated the exhibition “Battlefield Lens: Photographers of Indochina Wars 1950–1975” held at the Selegie Arts Centre.

Notes

-

Spector, R.H. (n.d.). The Vietnam War and the media. Retrieved from Britannica website. ↩

-

Conscription in the United States is commonly known as the draft. From a pool of around 27 million, the draft raised some 2.2 million American men for military service during the Vietnam War. ↩

-

There were three Indochina wars: First Indochina War (1945–54), the Second Indochina War or Vietnam War (1955–75) and the Third Indochina War (1975–91). ↩

-

The Battle of Dien Bien Phu took place between 13 March and 7 May 1954. The French fought against Viet Minh forces for the control of a small mountain outpost on the Vietnamese border near Laos. The Viet Minh, or League for the Independence of Vietnam, was formed by Ho Chi Minh to fight for Vietnamese independence from French rule. The Viet Minh’s victory over the French effectively ended the First Indochina War. ↩

-

Author’s interview with Chin Kah Chong, 11 September 2019. ↩

-

陈加昌 (Chen, J.C. [a.k.a. Chin Kah Chong]). (2011). 越南,我在现场:一个战地记者的回忆 (Vietnam, I was there: A war correspondent’s stories) (p. 258). 新加坡: 八方文化创作室. (Call no.: Chinese RSING 959.704 CJC) ↩

-

The Geneva Accords of 1954 resulted from a conference held in Geneva, Switzerland, from 26 April to 21 July 1954 that aimed to resolve the war between French and Viet Minh forces. There were representatives from Britain, France, China, the Soviet Union, the United States, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia and the State of Vietnam (later South Vietnam). The accords called for national elections in 1956 to reunify Vietnam. ↩

-

陈加昌, 2011; Author’s interview with Chin Kah Chong, 11 September 2019. ↩

-

Author’s interview with Chin Kah Chong, 11 September 2019. ↩

-

陈加昌 (Chen, J.C. [a.k.a. Chin Kah Chong]). (2015). 我所知道的李光耀 (LKY Whom I Knew). 新加坡: 玲子传媒私人有限公司. (Call no.: Chinese RSING 959.57051092 CJC-[HIS]) ↩

-

Author’s interview with Sam Yoke Tatt, 2011 and on 23 November 2019; Fass, H., & Page, T. (Eds.). (1997). Requiem: By the photographers who died In Vietnam and Indochina (p. 318). New York: Random House. (Call no.: RSEA q959.7043 REQ-WAR]) ↩

-

Author’s interview with Chin Kah Chong, 11 September 2019. ↩

-

Author’s interview with Chin Kah Chong, 21 November 2019. ↩

-

Hirashiki, Y. (2017). On the frontlines of the television war: A legendary war cameraman in Vietnam (p. 272). Philadelphia: Casemate Publishers. (Call no.: RSEA 959.70438 HIR-[WAR]) ↩

-

Author’s interview with Chin Kah Chong, 11 September 2019; oral interview with Sam Yoke Tatt, 23 November 2019; Hirashiki, 2017, pp. 272–273. ↩

-

Author’s interview with Sam Yoke Tatt, 23 November 2019. ↩

-

Author’s interview with Sam Yoke Tatt, 23 November 2019. ↩

-

Delany, K. (2006, September). The Saigon I left behind. Williams Alumni Review. Retrieved from Williams College website. ↩

-

Author’s interview with Chin Kah Chong in March 2011 for the Requiem exhibition held in Singapore from 13 June to 21 August 2011. ↩

-

Delany, Sep 2006. ↩

-

Author’s interview with the Chellapah family in April 2011 for the Requiem exhibition held in Singapore from 13 June to 21 August 2011. ↩

-

Nag, N. (Ed.). (2016). Inspirations of a nation: Tribute to 25 Singaporean South Asians (p. 30). Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co Pte Ltd. (Call no.: RSING 305.8914105957) ↩

-

Author’s interview with the Chellapah family in April 2011 for the Requiem exhibition held in Singapore from 13 June to 21 August 2011; Nag, 2016, p. 32. ↩

-

Tay, K.C. (1997, December 6). ‘I’m OK.’ Moments later, he was shot. The Straits Times, p. 28. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

During the Vietnam War, the tunnels were used by Viet Cong soldiers as hiding spots during combat. These also served as communication and supply routes, hospitals, food and weapon caches and even living quarters for the soldiers. The tunnels were instrumental to the Viet Cong in their fight against the American forces and helped to counter the growing American military effort. The 121-kilometre-long Cu Chi Tunnels are a popular tourist attraction today. ↩

-

Oral interview with the Chellapah family in April 2011 for the Requiem exhibition held in Singapore from 13 June to 21 August 2011. ↩

-

Fass & Page, 1997, p. 174. ↩

-

Chellapah, C. (1966, February 14). Vietnam War photographer’s last photo. Retrieved from Associated Press website. ↩

-

Author’s interview with the Chellapah family in April 2011 for the Requiem exhibition held in Singapore from 13 June to 21 August 2011. ↩