Marjorie Doggett: Photographer of Singapore

Edward Stokes reflects on Characters of Light by Marjorie Doggett, first published in 1957, and on his own recent book, Marjorie Doggett’s Singapore, which portrays her life and work here.

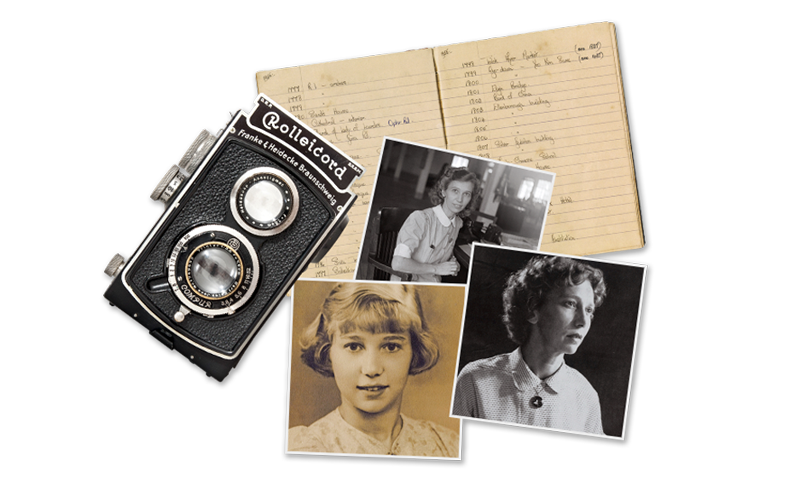

Montage showing the important logbook that Marjorie Doggett used to document her negatives (featuring two pages from the year 1955). The three portraits are of Marjorie at different stages of her life. The camera pictured – a medium-format Rolleicord – is similar to the one that Marjorie used to capture the images of Singapore for her 1957 photo book, Characters of Light.

Montage showing the important logbook that Marjorie Doggett used to document her negatives (featuring two pages from the year 1955). The three portraits are of Marjorie at different stages of her life. The camera pictured – a medium-format Rolleicord – is similar to the one that Marjorie used to capture the images of Singapore for her 1957 photo book, Characters of Light.

In 1957, a slender book titled Characters of Light: A Guide to the Buildings of Singapore was published.1 The book had been photographed and written by Marjorie Doggett, a 36-year-old English woman living in Singapore.2

The production was modest: 92 pages on low-quality wood-free paper, and in a relatively small format. With 79 photos accompanied by short captions, the work presents a loosely arranged selection of local buildings. However, in the coming years, the book would have a significant impact on the burgeoning awareness of local heritage, and the value of preserving the best of the city’s architecture from an earlier era.3

Significantly, Marjorie Doggett’s photos are the first seriously published visual record of Singapore’s urban landscape to have superbly captured many of the island’s grand structures as well as its more modest vernacular buildings. In the Urban Redevelopment Authority’s book, Conserving the Past, Creating the Future: Urban Heritage in Singapore (2011), geographer Lily Kong noted that Marjorie’s book “sought to record the beauty of the pre-war buildings at a time of impending change” and was an early example of a “stirring consciousness of the value of Singapore’s architectural heritage and historic districts”.4

Besides being the first photo book on Singapore’s buildings, Characters of Light is also notable because it was rare at the time for women to produce photo books, particularly outside the publishing centres of the United States, Britain and continental Europe. In Asia, the few women who did create photo books were virtually unknown, with Marjorie Doggett blazing the path.

Her Early Years

Born in 1921, Marjorie Joyce Millest grew up in Sutton, a large town located south of London. She was introduced to photography by a local chemist, who also taught her the basic skills in film development and printing.

In April 1940, Marjorie, then 19, began to compile her first photographic record: an album comprising her favourite town and landscape photos of England, images taken by a keen, self-taught amateur.

Almost seven years after starting work on this album, Marjorie, who had trained as a nurse and midwife during World War II, arrived in Singapore with her then fiancé Victor Doggett. Victor was two years her senior and had served in Singapore with the Royal Air Force from 1945 to 1946. After his return to Britain, demobilisation and subsequent reunion with Marjorie, the couple began planning for their future.

In January 1947, the young couple left England on the RMS Andes and arrived in Singapore on 9 February after a three-week journey.

Victor had hoped to set up a business in Singapore importing war surplus materials from Britain but the plans fell through. Thankfully he soon found a new vocation – teaching music. Over time, the income from The Music Studio that he opened would enable Marjorie to give up her job as a post-natal advisor for Nestlé and pursue her passion.

In the 1950s, Marjorie set out to create a photographic record of Singapore’s urban setting. In this, she was advised and urged on by two architects, Lincoln Page and T.H.H. Hancock, and a curator at the Raffles Museum, the polymath and photographer Dr Carl Alexander Gibson-Hill. Later, her energetic and equally demanding publisher Donald Moore took the lead.

Characters of Light

Marjorie shot most of the photographs in Characters of Light in 1955 and 1956, using a medium-format Rolleicord camera mounted on a tripod. She then developed the photos using a bedroom in her home on Amber Road as an improvised darkroom. The room was blacked out so that the prints could be developed and then washed in the nearby bathroom. Her son Nicholas recalls that she would “develop and print in the mornings, then open all the windows and doors to ventilate the bedroom”.5

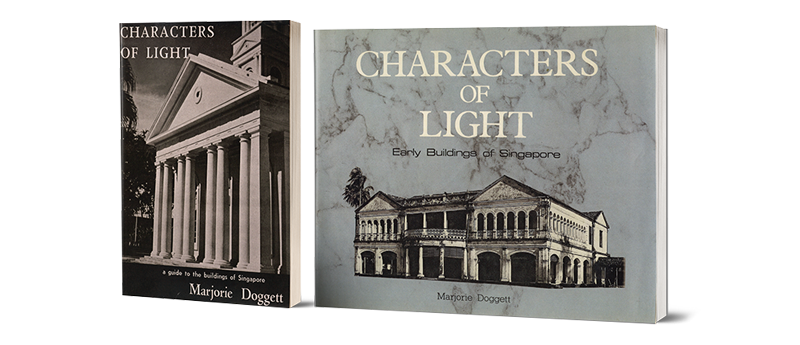

There are two editions of Characters of Light. The first in 1957 (left) features the Cathedral of the Good Shepherd on the cover. The cover of the second edition (right), published in 1985, shows “Joshua”, a mansion in Katong that was built around 1890.

There are two editions of Characters of Light. The first in 1957 (left) features the Cathedral of the Good Shepherd on the cover. The cover of the second edition (right), published in 1985, shows “Joshua”, a mansion in Katong that was built around 1890.

Marjorie recorded Singapore on the cusp of its physical transformation. Geographer Victor Savage sees 1959, two years after the publication of Characters of Light and the year Singapore was accorded self-government, as a watershed between “old” and “modern” Singapore. Thereafter, the gradual urban evolution that had marked the colonial era was replaced by rapid, planning-led development.6 Much of this aimed at remedying the housing shortage and the grim living conditions. Nonetheless, Marjorie foresaw the risks to heritage conservation that such progress would inevitably bring.

In addition to being a pioneering work, Characters of Light also stands out for Marjorie’s in-depth research into her subjects. Virtually alone among photographers of the time, she enriched her photographs with thoroughly researched and detailed captions. Thus, in later years, the book came to be valued by advocates for architectural conservation. Marjorie’s steady gaze made Characters of Light almost unique. Indeed, it was the aesthetic quality and the usefulness of the publication that helped mould her legacy.

After it was published, The Straits Times wrote that Characters of Light was “exactly the book of its kind that unknowingly we have been waiting for”.7 Meanwhile the Sunday Standard described the book as a “highly distinguished picture chronicle with clarity and simplicity”. The paper also suggested that, perhaps, Penang and Melaka should consider asking Marjorie to record their buildings as well.8

Marjorie and Victor Doggett at their Amber Road home in 1956, a year before the publication of Characters of Light.

Marjorie and Victor Doggett at their Amber Road home in 1956, a year before the publication of Characters of Light.

| THE MARJORIE DOGGETT COLLECTION AT THE NAS |

| Besides Characters of Light, the key source for this essay and Marjorie Doggett’s Singapore is the Marjorie Doggett Collection at the National Archives of Singapore (NAS) – a treasure trove of photos and documents. Marjorie Doggett’s care and discipline in keeping her photographic and other records effectively, if unknowingly, built the collection. |

| The Marjorie Doggett Collection was donated to the NAS by her son, Nicholas Doggett. This was advised by The Photographic Heritage Foundation which encourages its partners to donate such materials to public archives. The items are now being catalogued by the NAS and will be available for public access in 2022. |

| Two Doggett oral history recordings are also held by the NAS. These are the recollections of Victor Doggett, recorded in June 1990 with Daniel Chew, for the archives’ Oral History Centre; and the memories of Nick Doggett, primarily concerning his parents, recorded in November 2018 by Edward Stokes. The former is available online at www.nas.gov.sg/archivesonline/. |

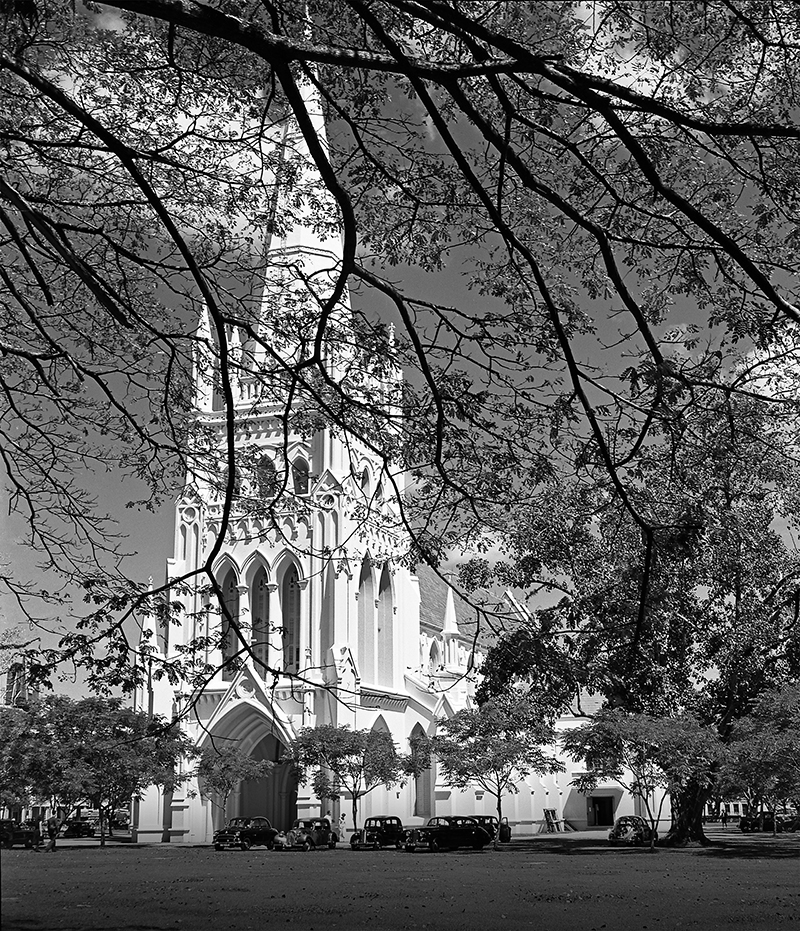

This photo of St Andrew’s Cathedral was taken in 1956 from a point near Coleman Street. Completed in 1861, the Anglican cathedral was designed by Ronald MacPherson and built by Indian convict labour. The original church on this site was designed by George D. Coleman and was completed in 1836. However, after two lightning strikes, it was demolished and replaced by this neo-Gothic structure. St Andrew’s Cathedral was gazetted as a national monument in 1973.

This photo of St Andrew’s Cathedral was taken in 1956 from a point near Coleman Street. Completed in 1861, the Anglican cathedral was designed by Ronald MacPherson and built by Indian convict labour. The original church on this site was designed by George D. Coleman and was completed in 1836. However, after two lightning strikes, it was demolished and replaced by this neo-Gothic structure. St Andrew’s Cathedral was gazetted as a national monument in 1973.

Taken in 1957 from Clifford Pier, Marjorie Doggett frames the Fullerton Building within one of the arches of the pier. The Fullerton Building was designed by government architects Major Percy Hubert Keys and Frank Dowdeswell. It was completed in 1928 and became synonymous with the General Post Office, a major and long-time tenant. Other tenants occupied the building for a time until its reopening in 2001 as The Fullerton Hotel Singapore. The restoration saw its Palladian-style architecture and grand Doric columns preserved and the introduction of modern interiors. In 2015, the building was gazetted as a national monument.

Taken in 1957 from Clifford Pier, Marjorie Doggett frames the Fullerton Building within one of the arches of the pier. The Fullerton Building was designed by government architects Major Percy Hubert Keys and Frank Dowdeswell. It was completed in 1928 and became synonymous with the General Post Office, a major and long-time tenant. Other tenants occupied the building for a time until its reopening in 2001 as The Fullerton Hotel Singapore. The restoration saw its Palladian-style architecture and grand Doric columns preserved and the introduction of modern interiors. In 2015, the building was gazetted as a national monument.

Later Life and Legacy

Marjorie Doggett had taken her photographs none too soon. Between 1947, when she and Victor arrived in Singapore, and 1961 when they became citizens, the population had doubled. The overcrowding that the colonial government’s urban redevelopment office, the Singapore Improvement Trust, had sought to remedy, albeit with insufficient finances and speed, was a primary – if not central – concern of the People’s Action Party, which formed the government in 1959. From then onwards, the pace of urban redevelopment escalated dramatically.

Following the 1966 Land Acquisition Act, Marjorie took a leading role in various architectural heritage debates. Noting Singapore’s recent achievements, in 1968 she wrote with genuine sympathy to The Straits Times concerning the planned demolition of the former Raffles Institution building in Bras Basah. Notwithstanding the anti-British sentiments of the time, Margaret foresaw that later generations of Singaporeans would come to cherish the city’s colonial-era buildings. She ended the letter with these words: “Our city will be poor indeed if, amongst all its dynamic modern environment and recreational activity, there is no place for the thinkers and ‘dreamers of dreams’.”9 Unfortunately, the school building was torn down in 1972.

The former Raffles Institution in Bras Basah, 1955. The building was originally designed by Lieutenant Philip Jackson with later extensions designed by George D. Coleman. It was demolished in 1972 and the site is currently occupied by the Raffles City complex. In 1968, Marjorie Doggett wrote to The Straits Times unsuccessfully calling for the school building to be preserved.

The former Raffles Institution in Bras Basah, 1955. The building was originally designed by Lieutenant Philip Jackson with later extensions designed by George D. Coleman. It was demolished in 1972 and the site is currently occupied by the Raffles City complex. In 1968, Marjorie Doggett wrote to The Straits Times unsuccessfully calling for the school building to be preserved.

By the mid-1980s however, while Marjorie continued to maintain an interest in the preservation of historic buildings, her main focus was animal welfare work. She was a founding member of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in 1954 (today known as the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, Singapore). In 1982, she became an advisor to the World Society for the Protection of Animals and the secretary of the International Primate Protection League.

A side view of Yin Fo Fui Kun with a five-footway, 1955. This is a Hakka clan house located at the junction of Cross Street and Telok Ayer Street. It was built around 1882. Light and shadows cast by the window rain canopies and shelters play off each other on the building’s off-white chunam walls. The building was gazetted as a national monument in 1998.

A side view of Yin Fo Fui Kun with a five-footway, 1955. This is a Hakka clan house located at the junction of Cross Street and Telok Ayer Street. It was built around 1882. Light and shadows cast by the window rain canopies and shelters play off each other on the building’s off-white chunam walls. The building was gazetted as a national monument in 1998.

Marjorie and her family also made countless butterfly collecting trips to Malaysia. By the 1990s, the trips had resulted in a Lepidoptera collection of significant value. Today, this collection is held by the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum.

Her husband Victor, who taught music and was also a music journalist and critic, died in 2005. Marjorie herself passed away peacefully at home on 15 August 2010 at the age of 89. Her son Nicholas was with her, as was Fina, her loyal helper. Seven years later, in recognition of her contributions to animal welfare, Marjorie was inducted into the Singapore Women’s Hall of Fame.

How “Marjorie Doggett’s Singapore” Came to Be

I first seriously studied Characters of Light at the National Library of Singapore. From its pages, photo after photo leapt up of 1950s Singapore, though with poor reproduction. The potential was intriguing. Might her negatives still exist? If so, what was their quality like? And, equally important, what was their present physical condition? And what about her life story? Did any personal or perhaps professional records exist? My photographer’s instinct – that no one with Marjorie’s method and dedication would lose or abandon her negatives – urged me on.

Soon after, I sought out Marjorie’s son Nick by telephone and we met in January 2011. Nick told me that his mother’s photographs and documents were safely stored in his home. My first visit to Nick’s Changi bungalow in July 2011 was a poignant moment. In handling negatives, prints and documents unseen for decades, I saw first-hand the depth and breadth of Marjorie’s work. Sorting through boxes dating back to the 1950s, Singapore, as it then was, came to life. The image quality in the negatives and prints was vastly superior to the reproductions found in the 1957 and the 1985 editions of Characters of Light.

Nick and I developed a shared resolve: to create a record of Marjorie’s life and work in book form and to have her materials donated to the National Archives of Singapore. With the donation to the archives completed in 2016, the next goal was to prepare and publish Marjorie Doggett’s Singapore.

Marjorie Doggett in the late 1990s with the family’s mongrel Wurst (front) and a neighbour’s dog. In 1954, she became a founding member of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. In some ways, Marjorie's advocacy work for animal rights has eclipsed her career as a photographer.

Marjorie Doggett in the late 1990s with the family’s mongrel Wurst (front) and a neighbour’s dog. In 1954, she became a founding member of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. In some ways, Marjorie's advocacy work for animal rights has eclipsed her career as a photographer.

The selection of photos and documentary research for the book were carried out between late 2017 and 2018. In a small room at the National Library, I spent three months immersed in the materials: negatives, prints, photo notebooks, letters, diaries, newspaper cuttings, invitations and much more. But one particular item was of exceptional value; indeed it became a virtual bible for much of my research. From 1952 until the early 1970s, Marjorie kept a logbook of her negatives. It records, with method and care almost beyond imagination, every photograph that she took during those years. Each is meticulously identified by year and place. By checking off the original negatives, we know that not once did Marjorie err. Thus, her photos can be given precise years as to when they were taken.

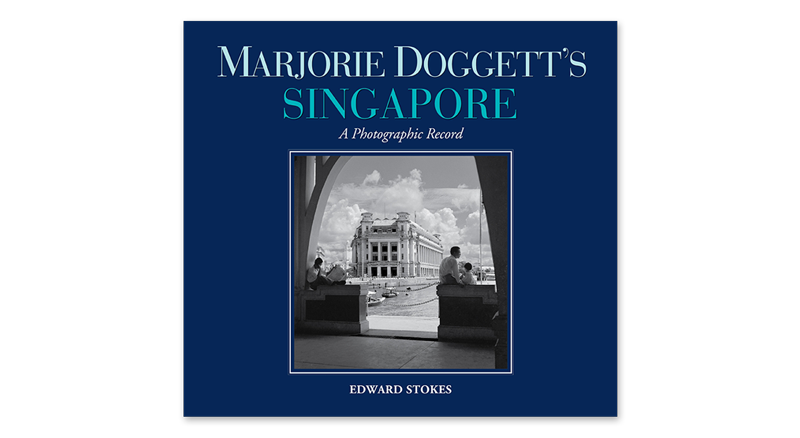

The heart of Marjorie Doggett’s Singapore are the photographs from Characters of Light, categorised and rearranged into completely different sections from the earlier editions. The book is also accompanied by a number of previously unpublished photographs, both taken by her, as well as photographs of her and her family. In putting together this book, I hope to introduce readers to Marjorie Doggett’s life and work, and to Singapore in the 1950s.

All photos by and of Marjorie Doggett © National Archives of Singapore.

|

| MARJORIE DOGGETT’S SINGAPORE Marjorie Doggett’s Singapore: A Photographic Record was published in November 2019. It was originated by The Photographic Heritage Foundation and co-published with Ridge Books, an imprint of NUS Press. The work was supported by funding from Ng Teng Fong Charitable Foundation. The book and this essay were put together based on the Marjorie Doggett Collection held by the National Archives of Singapore. The photos in the collection portray Marjorie Doggett’s life and work, as well as Singapore’s urban setting and architecture in the 1950s. Marjorie Doggett’s Singapore is available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries (Call nos.: RSING 959.5704 DOG-[HIS] and SING 959.5704 DOG-[HIS]). It also retails at major bookshops in Singapore. |

Edward Stokes is an Australian photographer and writer. He has a special interest in the photographic history of Asia. The founder and publisher of The Photographic Heritage Foundation, Edward’s many books about Hong Kong and Australia have been widely praised for blending photographs with illuminating historical texts. He was educated at Magdalen College, Oxford.

Edward Stokes is an Australian photographer and writer. He has a special interest in the photographic history of Asia. The founder and publisher of The Photographic Heritage Foundation, Edward’s many books about Hong Kong and Australia have been widely praised for blending photographs with illuminating historical texts. He was educated at Magdalen College, Oxford.

NOTES

-

The Marjorie Doggett Collection, with negatives, prints and documents, provided the primary research foundation for Marjorie Doggett’s Singapore and this essay. The materials were arranged in detail by Edward Stokes for his research needs. However, as the collection is currently being formally catalogued by the National Archives of Singapore, it is not possible here to give specific text references. ↩

-

Doggett, M. (1957). Characters of light: A guide to the buildings of Singapore. Singapore: Donald Moore. (Call no.: RCLOS 725.4095957 DOG) ↩

-

Characters of Light was reissued in 1985 as an expanded edition by Times Books International with 138 pages and 107 photos. It used glossy paper and kept most of the images featured in the 1957 publication, with the addition of 38 new photos. The captions were lengthened as well. Notably, given Singapore’s urban transformation since 1957, Marjorie Doggett’s texts made stronger comments on heritage and architectural preservation. See Doggett, M. (1985). Characters of light: Early buildings of Singapore. Singapore: Times Books International. (Call no.: RSING 722.4095957 DOG) ↩

-

Kong, L. (2011). Conserving the past, creating the future: Urban heritage in Singapore (p. 30). Singapore: Urban Redevelopment Authority. (Call no.: RSING 363.69095957 KON) ↩

-

Stokes, E. (2019). Marjorie Doggett’s Singapore: A photographic record (p. 25). Singapore: Ridge Books: The Photographic Heritage Foundation. (Call no.: RSING 959.5704 DOG-[HIS]) ↩

-

Teo, S.E., & Savage, V.R. (1991). Singapore landscape: A historical overview of housing image (p. 336). In E.C.T. Chew & E. Lee (Eds), A history of Singapore. Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 HIS-[HIS]) ↩

-

Enduring epitaphs. (1957, June 3). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

A picture chronicle of S’pore buildings. (1957, June 30). Sunday Standard, p. 23. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Doggett, M. (1968, July 13). Preserving Singapore history. The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩