History Through Postcards

One postcard may not say much, but a collection of postcards can speak volumes. Stephanie Pee tells us what Postcard Impressions of Early 20th-century Singapore has to say.

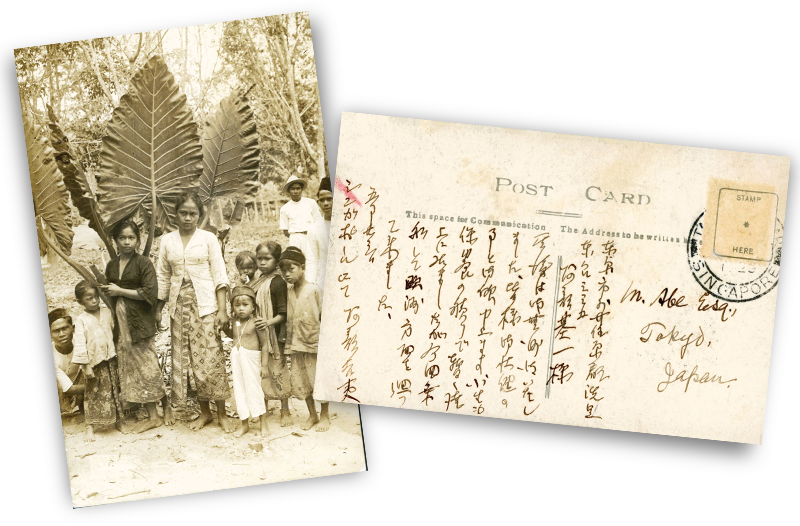

This undated postcard features a group of villagers in traditional Malay attire. Japanese travellers would send postcards featuring scenes such as this back home as a way of sharing their experiences abroad. In this card, the writer conveys his general greetings and notes that he is fine in Singapore. Accession no.: B29626253B_0047.

This undated postcard features a group of villagers in traditional Malay attire. Japanese travellers would send postcards featuring scenes such as this back home as a way of sharing their experiences abroad. In this card, the writer conveys his general greetings and notes that he is fine in Singapore. Accession no.: B29626253B_0047.

These days, when we want to chat with friends and family living abroad, we just pick up our smartphones. The ability to communicate cheaply and easily with someone who lives thousands of kilometres away is something that we take for granted.

This was not the case even 30 years back, let alone 100 years ago. And while early 20th-century Singapore did have telephone and telegraph links with the rest of the world, most people could only afford to communicate using letters and postcards.

Postcards, in particular, were popular. Although space was limited and the messages written were exposed for all to see, postcards were affordable and, more importantly, allowed the sender to share images of distant lands. Very quickly, people began collecting them and, over time, old postcards have become a valuable source of information about the past.

Scenes such as this gave recipients an idea of what Singapore was like. Addressed to Mr J. Takeda in Tokyo, this postcard features the Central Police Station on South Bridge Road (left) as well as the vessel S.S. Sanuki Maru of the Nippon Yūsen Kaisha (bottom right). The sender says that he has arrived in Singapore and is awaiting his ship to Java. He also notes that the steamy temperature on board the ship (86–88°F or 30–31°C) is similar to Singapore’s weather. Postmarked 22 October 1907. Publisher: Nippon Yūsen Kaisha. Accession no.: B32413805D_0093.

Scenes such as this gave recipients an idea of what Singapore was like. Addressed to Mr J. Takeda in Tokyo, this postcard features the Central Police Station on South Bridge Road (left) as well as the vessel S.S. Sanuki Maru of the Nippon Yūsen Kaisha (bottom right). The sender says that he has arrived in Singapore and is awaiting his ship to Java. He also notes that the steamy temperature on board the ship (86–88°F or 30–31°C) is similar to Singapore’s weather. Postmarked 22 October 1907. Publisher: Nippon Yūsen Kaisha. Accession no.: B32413805D_0093.

The first official postcards in Singapore were issued by the Straits Settlements government in 1879.1 By the 1900s, the sale of private picture postcards had become a profitable business, with many international and local publishing firms entering the market.2 Other factors that contributed to this growth include the affordability and availability of such privately printed picture postcards, and the inexpensive postal rates for postcards in 1905.

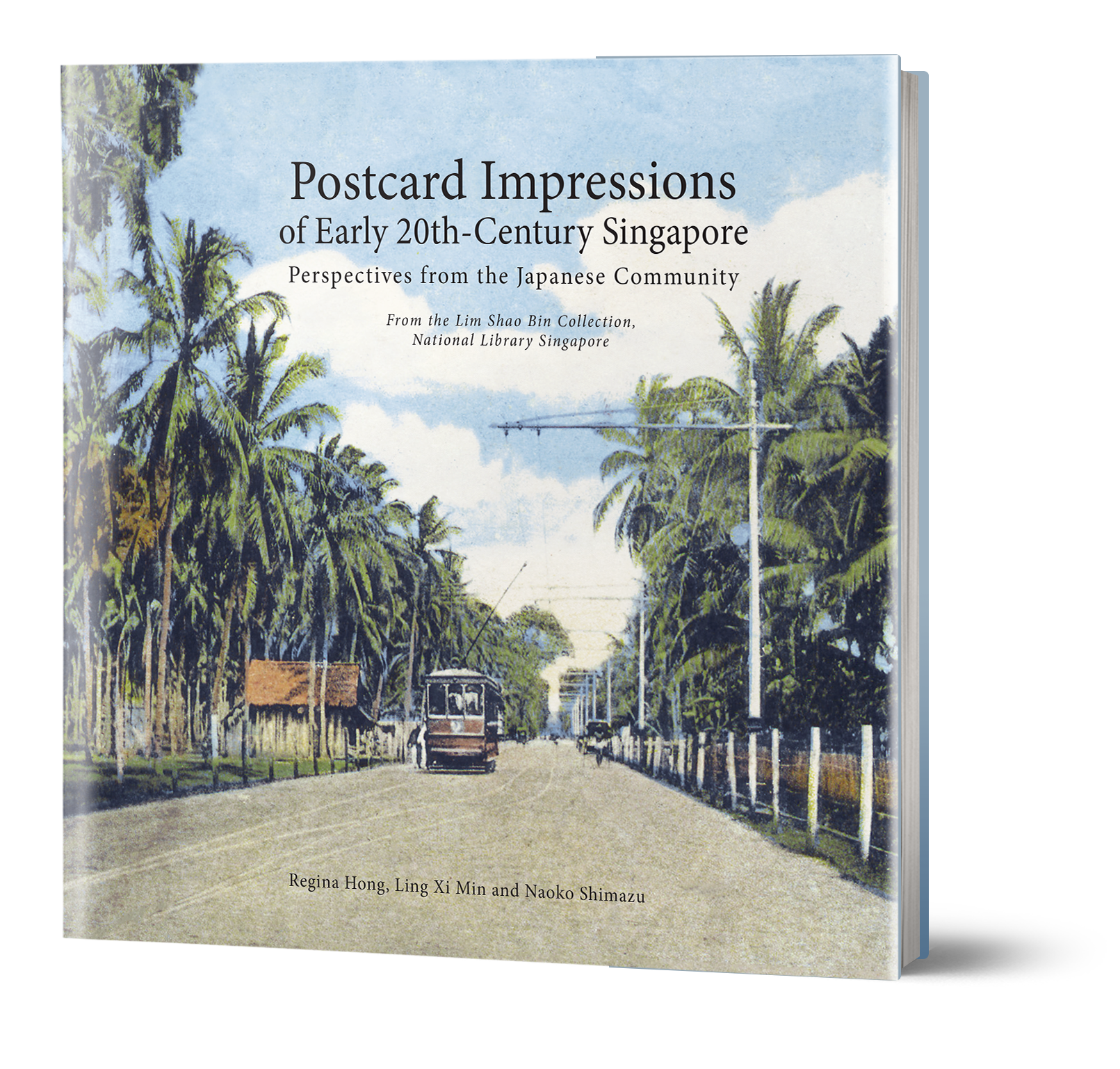

A selection of some 160 Japanese postcards from the National Library’s Lim Shao Bin Collection – spanning the early 20th century to the 1940s – was recently published in the hardcover book Postcard Impressions of Early 20th-century Singapore. These comprise postcards featuring Japanese subject matter; postcards produced in Japan or by Japanese photographic studios, printers and stationers based in Singapore or Malaya; and postcards bearing messages written in Japanese.

The postcards printed in Singapore feature scenes and activities of a bygone era: tranquil beaches, old buildings that have since been demolished, rubber plantations, fishing villages as well as flora and fauna. The brief messages on the postcards written by early Japanese residents in Singapore offer a glimpse into their daily lives here.

Postcard Impressions of Early 20th-century Singapore looks at three different categories of postcards: those with maps featuring Singapore; those that show how Singapore was perceived by Japanese travellers; and those that illustrate characteristics of the pre-war Japanese community here.

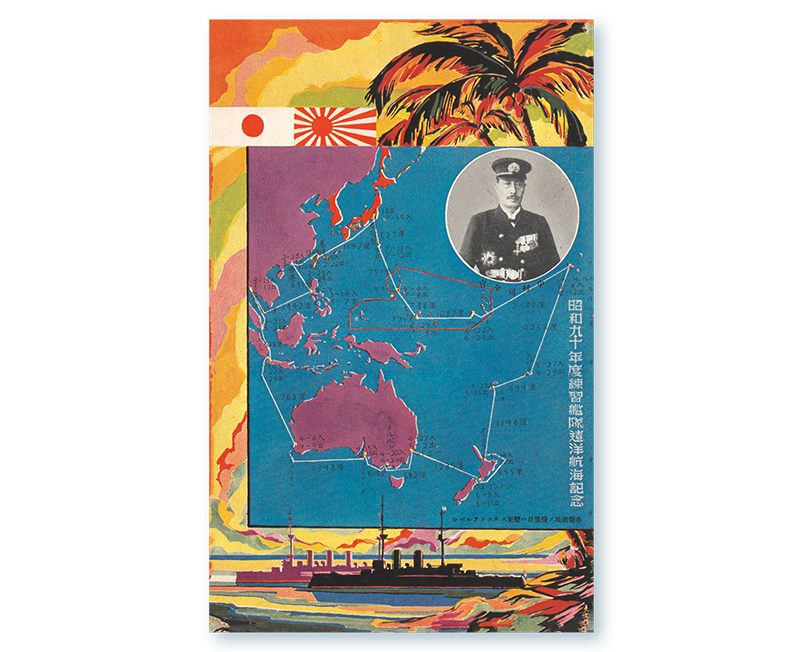

This postcard was posted from the warship Asama by Major Ōhashi Kyōzō and mailed to an address in Aichi prefecture. Being a military postcard, it did not require a postage stamp. The postcard shows a tropical sunset and two coconut trees set within a frame. The motif of the coconut tree was frequently used to evoke the exotic South Seas (Nanyō, or Nanyang) after the Japanese colonisation of Taiwan in 1895. The postcard was produced in commemoration of the Japanese Navy’s overseas training voyage from 1934 to 1935, which included Singapore (written in katakana characters) as a stopover. Postmarked 1 January 1935. Printed by Tokyo Shibaura Asahi Printing Company. Accession no.: B32413808G_0026.

This postcard was posted from the warship Asama by Major Ōhashi Kyōzō and mailed to an address in Aichi prefecture. Being a military postcard, it did not require a postage stamp. The postcard shows a tropical sunset and two coconut trees set within a frame. The motif of the coconut tree was frequently used to evoke the exotic South Seas (Nanyō, or Nanyang) after the Japanese colonisation of Taiwan in 1895. The postcard was produced in commemoration of the Japanese Navy’s overseas training voyage from 1934 to 1935, which included Singapore (written in katakana characters) as a stopover. Postmarked 1 January 1935. Printed by Tokyo Shibaura Asahi Printing Company. Accession no.: B32413808G_0026.

Mapping the World

Maps and shipping routes were frequently featured on postcards issued by Japanese shipping companies, such as Nippon Yūsen Kaisha, whose vessels often carried both passengers and cargo. These postcards depict maps that traced important transnational shipping routes, indicating their dates of arrival at different ports-of-call, including Singapore.

These postcards also conveyed information to potential customers about a company’s major shipping routes and schedules, and enabled families of travellers to track their loved ones’ journeys. The postcards generally point to Singapore as an important port along major international shipping routes.

Japanese economic migrants were another group of travellers who made use of postcards to communicate with families back home. In the 19th century, the Japanese government encouraged migration as a means of managing its growing population and alleviating the pressures faced by its domestic economy. These people made their way to destinations such as the United States, Canada, Europe and even Brazil. Migrants headed for these countries often stopped over in Singapore and took the opportunity to send a postcard home.

Included in the book are postcards issued by the Imperial Japanese Navy. Singapore was an important port-of-call for training voyages, which honed the technical skills of rookie cadets by exposing them to conditions in the Pacific Ocean as well as to raise public awareness of the Nanyō (South Seas, or Nanyang).3 These training voyages also signalled Japan’s increasing knowledge of current political developments unfolding beyond its shores.

In addition, the book features commemorative postcards marking the fall of Singapore in February 1942. These were issued by the Imperial Japanese postal service, which also came up with special postmarks and postage stamps.

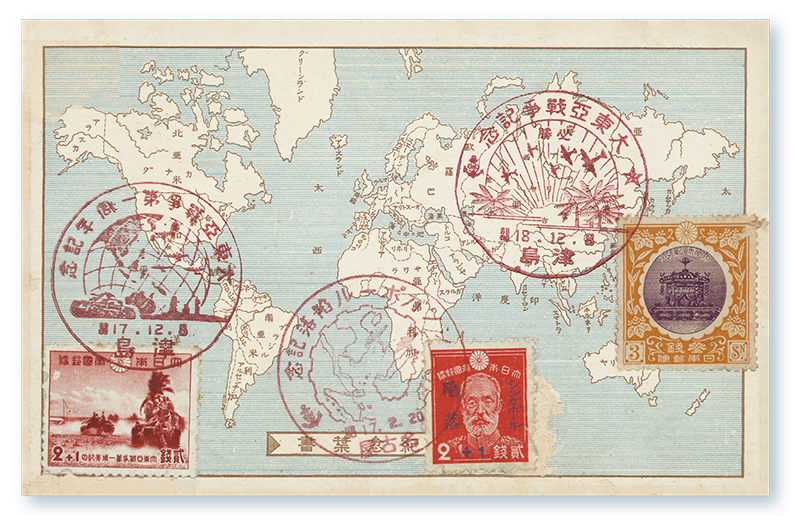

Produced to mark the fall of Singapore in February 1942, this postcard features three different commemorative postmarks and postage stamps. A Japanese stamp collector had intentionally visited the post office on three separate occasions to collect these postmarks. From the left: the first anniversary of the Pacific War (dated 8 December 1942); the fall of Singapore (dated 20 February 1942 at Nagoya); and the second anniversary of the Pacific War (dated 8 December 1943). Dated 1942 and 1943. Accession no.: B32413808G_0030.

Produced to mark the fall of Singapore in February 1942, this postcard features three different commemorative postmarks and postage stamps. A Japanese stamp collector had intentionally visited the post office on three separate occasions to collect these postmarks. From the left: the first anniversary of the Pacific War (dated 8 December 1942); the fall of Singapore (dated 20 February 1942 at Nagoya); and the second anniversary of the Pacific War (dated 8 December 1943). Dated 1942 and 1943. Accession no.: B32413808G_0030.

Early Japanese Tourists

Early Japanese tourists to Singapore only had a few reliable sources to turn to for travel information: word-of-mouth from family and friends, published writings by other travellers (such as travel guidebooks) and, of course, postcards sent by acquaintances who had been on similar journeys.

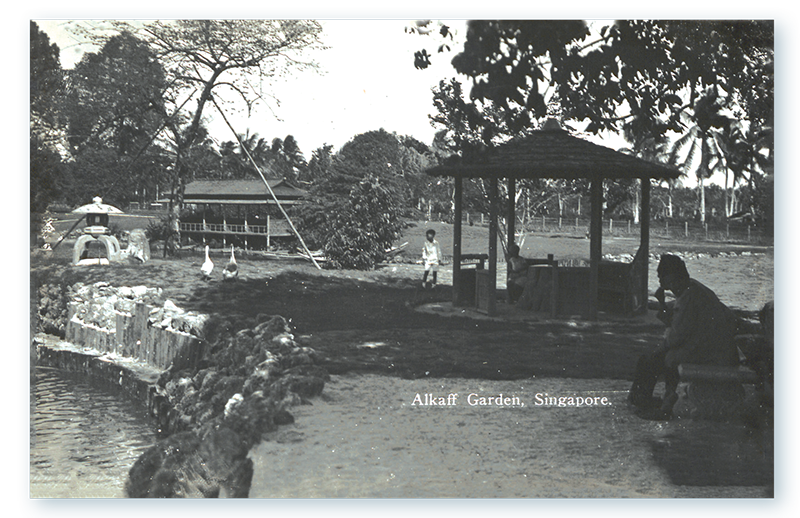

Alkaff Gardens was built in 1930 in the style of a Japanese park, and was a popular destination among locals and Japanese tourists. The garden had a Japanese teahouse that served “refreshments all day and night until 12 o'clock”. The picture on this undated postcard is also featured in an advertisement for Alkaff Gardens published in the 31 May 1930 issue of the Malayan Saturday Post, suggesting that the postcard had been specially commissioned to publicise the garden. On the far left of the picture is a traditional Japanese lantern made of stone called a tōrō. The garden, which was located near the former Bidadari Cemetery, closed in December 1941 in preparation for war. Cedar Girls’ Secondary School currently occupies the site. Accession no.: B32413806E_0002.

Alkaff Gardens was built in 1930 in the style of a Japanese park, and was a popular destination among locals and Japanese tourists. The garden had a Japanese teahouse that served “refreshments all day and night until 12 o'clock”. The picture on this undated postcard is also featured in an advertisement for Alkaff Gardens published in the 31 May 1930 issue of the Malayan Saturday Post, suggesting that the postcard had been specially commissioned to publicise the garden. On the far left of the picture is a traditional Japanese lantern made of stone called a tōrō. The garden, which was located near the former Bidadari Cemetery, closed in December 1941 in preparation for war. Cedar Girls’ Secondary School currently occupies the site. Accession no.: B32413806E_0002.

These postcards provided their recipients with an inkling of life in Singapore as well as ideas of places to visit, sights to see and foods to savour. These scenes fostered perceptions of Singapore as a romantic, tropical destination worthy of a visit, which in turn fuelled the sale of such memorabilia.

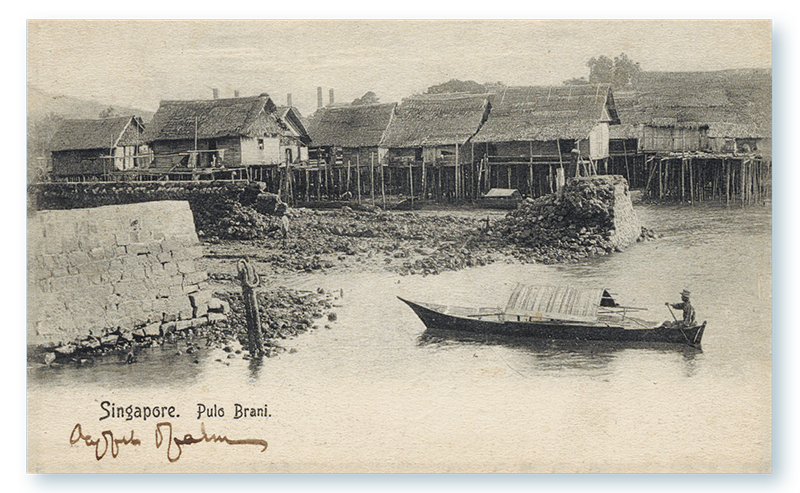

Recurring images featured on postcards include fishing villages on Pulau Brani, tree-lined beaches, street views and buildings such as St Andrew’s Cathedral.

Idyllic fishing villages were very likely the first scenes that greeted travellers when they set foot on Singapore.4 The sight was a great source of fascination to Japanese travellers, and was frequently mentioned in their written and illustrated accounts of the island.5

Sampans and serene fishing villages off Pulau Brani were sights early visitors to Singapore might have seen as they arrived on the island. This postcard was addressed to someone in Russia but appears not to have been sent. Publisher: Wilson & Co. for Hotel de l’Europe & Orchard Road, Singapore. Accession no.: B32413807F_0004.

Sampans and serene fishing villages off Pulau Brani were sights early visitors to Singapore might have seen as they arrived on the island. This postcard was addressed to someone in Russia but appears not to have been sent. Publisher: Wilson & Co. for Hotel de l’Europe & Orchard Road, Singapore. Accession no.: B32413807F_0004.

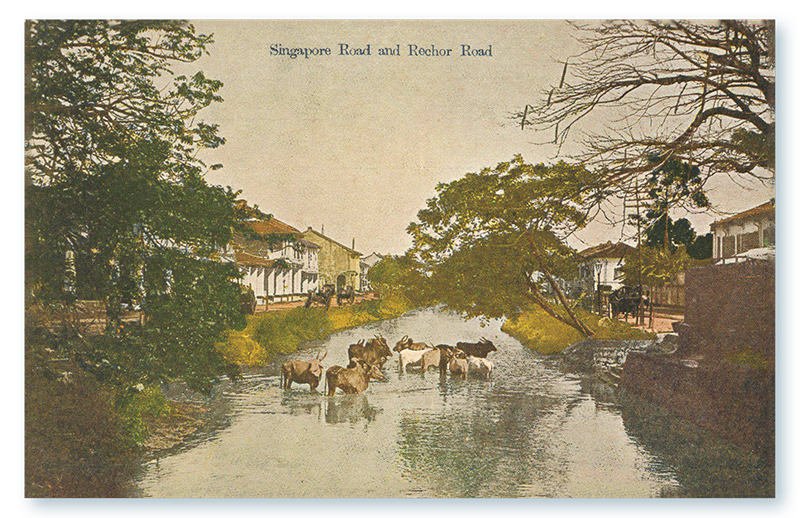

A small herd of cattle in a river, possibly the Rochor River, that once flowed in the vicinity of Selegie and Rochor Canal roads. Accession no.: B32413805D_0171.

A small herd of cattle in a river, possibly the Rochor River, that once flowed in the vicinity of Selegie and Rochor Canal roads. Accession no.: B32413805D_0171.

The photo featured on this undated postcard is part of a series of four photographs titled “A Big Snake Swallowing a Deer”. The photos depict the snake with its distended belly, its capture and the subsequent release of the deer from its stomach. Postcards like this suggest that there was a market for such exotica in Singapore. Accession no.: B32413807F_0146.

The photo featured on this undated postcard is part of a series of four photographs titled “A Big Snake Swallowing a Deer”. The photos depict the snake with its distended belly, its capture and the subsequent release of the deer from its stomach. Postcards like this suggest that there was a market for such exotica in Singapore. Accession no.: B32413807F_0146.

This postcard featuring the Botanic Gardens was addressed to T. Matsuki in Tokyo. The brief message on the front of the postcard says that the sender is writing from “far away” and that the picture is of Singapore. Postmarked 15 March 1906 (Singapore); 19 March 1906 (Hong Kong); 24 March 1906 (Tokyo). Accession no.: B32440324K_0011.

This postcard featuring the Botanic Gardens was addressed to T. Matsuki in Tokyo. The brief message on the front of the postcard says that the sender is writing from “far away” and that the picture is of Singapore. Postmarked 15 March 1906 (Singapore); 19 March 1906 (Hong Kong); 24 March 1906 (Tokyo). Accession no.: B32440324K_0011.The postcards in the book are from a collection donated by researcher and collector Lim Shao Bin to the National Library Board.

Lim began collecting Japanese historical materials on Singapore and Southeast Asia when he was living in Japan in the 1980s. Between 2016 and 2020, he donated more than 1,500 items to the National Library Board, which had been painstakingly amassed over a 30-year period.

The collection represents a rich resource for the study of the pre-war Japanese community in Singapore as well as Japan’s military expansion and subsequent occupation of Southeast Asia during World War II. It comprises maps, newspapers, postcards, books, periodicals, primary documents and ephemera dating from the 1860s to the 2000s. Notable items include Japanese wartime maps and some of the earliest locally published Japanese guides on Singapore – *Harada’s Guide* (1919) and *Shingapōru Gaiyō* (1923).

Lim donated these rare materials to encourage research and scholarship into an important period of Singapore’s multifaceted history.

REFERENCES

For more information on the collection, see Lee, G. (2018, Jul–Sep). Japan in Southeast Asia: The Lim Shao Bin Collection. BiblioAsia, 14 (2). (Retrieved from BiblioAsia website)

Lim Shao Bin is the editor of Images of Singapore from the Japanese Perspective (1868–1941), which contains over 1,000 images from postcards, maps and photo albums that trace shifting Japanese perspectives of Singapore. See Lim, T.W. & Lim, S.B. (2004). Images of Singapore from the Japanese perspective (1868–1941). Singapore: The Japanese Cultural Society. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 IMA-[HIS])

Early Japanese Community

The early Japanese community in Singapore comprised traders, businessmen, professionals and sex workers known as karayuki-san. The postcards in the book provide us with a sense of their lives here.

Part of the Lim Shao Bin Collection includes a set of postcards documenting the correspondence between businessman Ejiri Koichirō and his friend Tajika Shōjiro, spanning a decade across various countries. These postcards give us an idea of how early migrants adapted to life in Singapore. Some of the postcards exchanged between the two men are featured in the book.

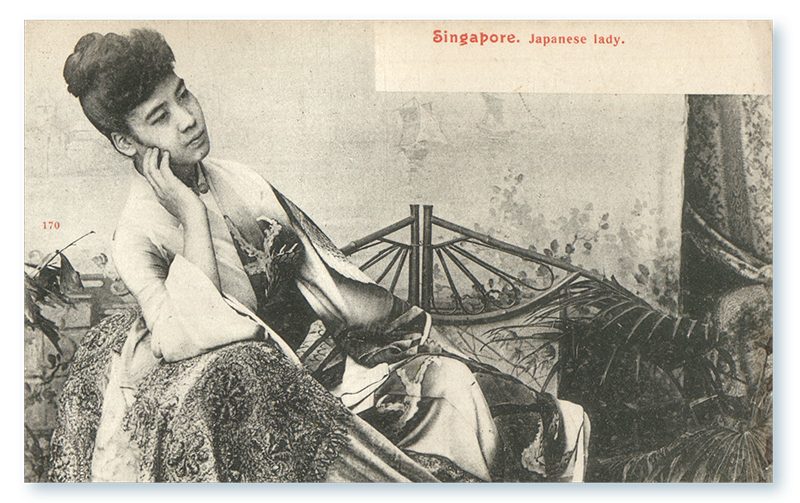

One group of Japanese migrants who received particular attention in postcards are the karayuki-san. Many of these women were from the poor, rural regions of Kyushu island and had been sold or kidnapped, and subsequently forced into the sex trade overseas. While often ostracised or looked down upon, they played an important role in Japan’s economic and social fabric as their presence supported fledgling local Japanese businesses (and in turn the wider Japanese economy). The women even responded to disaster relief efforts in Japan by sending home much-needed funds and supplies.

This undated postcard features a Japanese woman, likely a karayuki-san, in her kimono. Karayuki-san, or Japanese prostitutes, sometimes posed for a fee at the request of photographers in Singapore. Accession no.: B32440324K_0076.

This undated postcard features a Japanese woman, likely a karayuki-san, in her kimono. Karayuki-san, or Japanese prostitutes, sometimes posed for a fee at the request of photographers in Singapore. Accession no.: B32440324K_0076.

Some postcards featured the karayuki-san posing provocatively in their kimonos, which reinforced the image of Singapore “as a centre of romanticism, exoticism, and easy sex”.6 Regardless whether the women were indeed karayuki-san or whether they were even living in Singapore, the fact that these postcards were bought and used suggests that the women formed part of the impressions that early travellers held of Singapore.

As not much has been written about the pre-war Japanese community in Singapore, these postcards provide insights into the lives of these migrants and their social networks, and also offer new perspectives of Singapore society in the early 20th century.

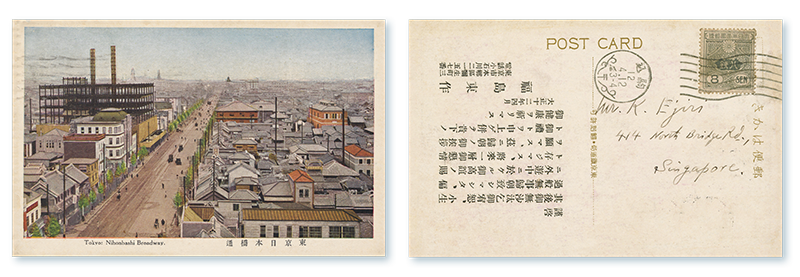

Featuring the Nihonbashi Broadway in Tokyo, this postcard was sent by Fukujima Tōsaku to Ejiri Koichirō, the proprietor of the pharmacy, K. Ejiri & Co., in Singapore. Fukujima had visited Ejiri in Singapore. On the reverse of the postcard is a stock message to inform those who had hosted Fukujima during his travels that he had returned safely to Japan and to thank them for their kind hospitality. Dated April 1923. Accession no.: B32413805D_0100.

Featuring the Nihonbashi Broadway in Tokyo, this postcard was sent by Fukujima Tōsaku to Ejiri Koichirō, the proprietor of the pharmacy, K. Ejiri & Co., in Singapore. Fukujima had visited Ejiri in Singapore. On the reverse of the postcard is a stock message to inform those who had hosted Fukujima during his travels that he had returned safely to Japan and to thank them for their kind hospitality. Dated April 1923. Accession no.: B32413805D_0100.

Postcard Impressions of Early 20th-century Singapore: Perspectives from the Japanese Community, researched and written by Regina Hong, Ling Xi Min and Professor Naoko Shimazu, is co-published by the National Library, Singapore, and Marshall Cavendish International (Asia). The book is available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries ([Call nos.: RSING 959.57 HON-[HIS] and SING 959.57 HON-[HIS]](https://eservice.nlb.gov.sg/item_holding.aspx?bid=204353382)). It also retails at major bookshops in Singapore.

Postcard Impressions of Early 20th-century Singapore: Perspectives from the Japanese Community, researched and written by Regina Hong, Ling Xi Min and Professor Naoko Shimazu, is co-published by the National Library, Singapore, and Marshall Cavendish International (Asia). The book is available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries ([Call nos.: RSING 959.57 HON-[HIS] and SING 959.57 HON-[HIS]](https://eservice.nlb.gov.sg/item_holding.aspx?bid=204353382)). It also retails at major bookshops in Singapore. Stephanie Pee is an Assistant Manager with the Publishing department at the National Library, Singapore. She edits publications produced by the National Library and manages book projects.

Stephanie Pee is an Assistant Manager with the Publishing department at the National Library, Singapore. She edits publications produced by the National Library and manages book projects.

NOTES

-

Cheah, J. S. (2006). Singapore: 500 early postcards (p. 8). Singapore: Editions Didier Millet. (Call no.: RSING 769.566095957 CHE) ↩

-

National Archives. (1986). Singapore historical postcards from the National Archives Collection (p. 8). Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Call no.: RSING 769.95957 SIN) ↩

-

Schencking, J.C. (1999, October). The Imperial Japanese Navy and the constructed consciousness of a South Seas destiny, 1872–1921. Modern Asian Studies, 33 (4), 769–796, pp. 772–73. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Nishihara suggests that Pulau Brani was likely the model for the water villages depicted in the works of Shikō Imamura’s (今村紫紅) Scrolls of Tropical Countries (Morning Scroll) [熱国之巻(朝之巻)] [Nekkoku no Maki (Asa no Maki)], which was designated as an important cultural property in Japan, indicating that the sight of Pulau Brani likely constituted one of the key Japanese perspectives of Singapore. 西原大輔 [Daisuke Nishihara]. (2017). 日本人のシンガポール体験:幕末明治から日本占領下・戦後まで [Nihonjin no Shingapōru Taiken: Bakumatsumeiji kara nihonsenryōka.sengo made] (p. 88). Kyoto, Japan: Jinbun Shoin. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Nishihara, 2017, p. 88. ↩

-

Warren, J. (1993). Ah ku and karayuki-san: Prostitution in Singapore (p. 252). Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 306.74095957 WAR) ↩