Keong Saik Road: The Other Side of the Red-Light District

Charmaine Leung relives the sights and sounds of Keong Saik Road – where she lived in the 1970s and 80s – and says it has more to offer than its former notoriety.

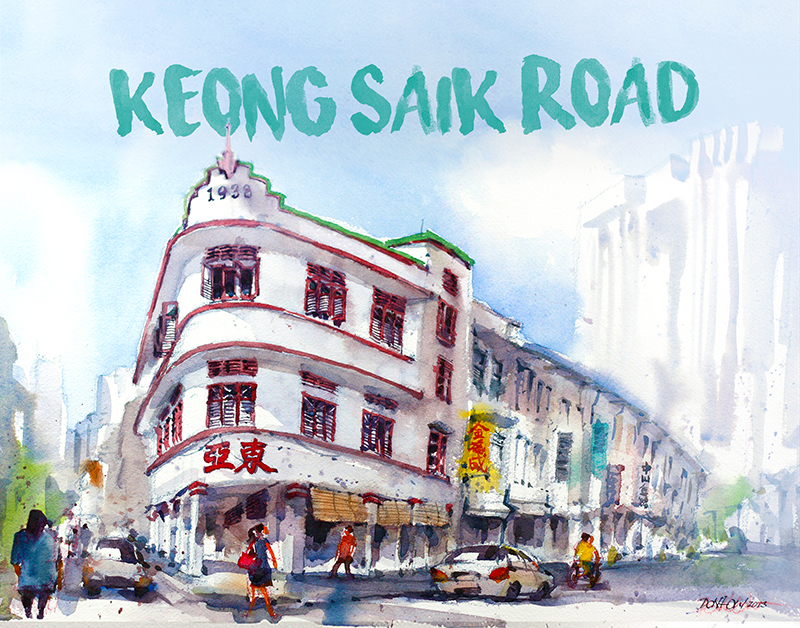

The iconic Tong Ah Eating House at the junction of Keong Saik and Teck Lim roads. Watercolour painting by Don Low, 2014. Courtesy of Don Low.

The iconic Tong Ah Eating House at the junction of Keong Saik and Teck Lim roads. Watercolour painting by Don Low, 2014. Courtesy of Don Low.

If I were to think of Keong Saik as a person, it would be a woman. In particular, I see an elderly lady who is hardworking, loyal and reliable, tirelessly working to provide for her family and her employers.

This image, long entrenched in my mind, is an impression very much influenced by Auyong Foon – someone I called “grandaunt”. Auyong Foon was not a relative but a dear friend of my grandmother’s, and I was fortunate to have spent my formative years in her company – an experience I treasure immensely. She was my favourite grandaunt and I fondly addressed her as Foon Yee Por (“Yee Por” is a Cantonese term used to address female contemporaries of one’s grandmother).

The Indomitable Majie

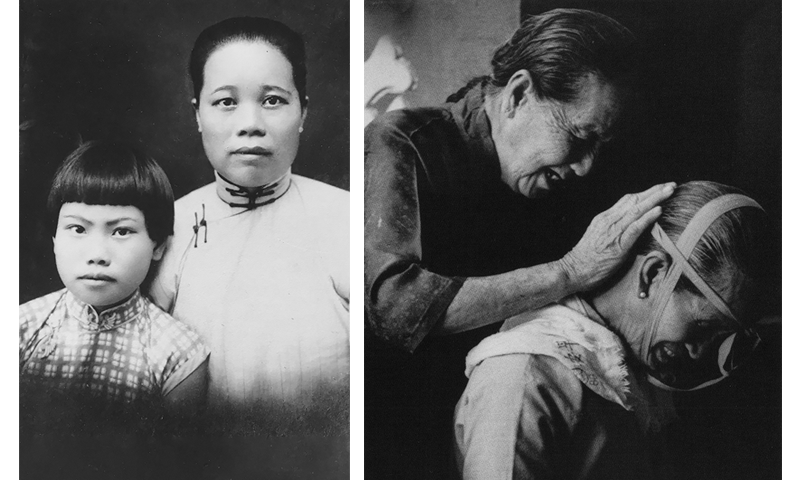

Both Foon Yee Por and my grandmother were majie (妈姐) – a term referring to Chinese women who journeyed to Southeast Asia in search of a better life in the 1930s, working mainly as domestic servants in the homes of wealthy families.1

These Cantonese women, from the Pearl River Delta in Guangdong province, left behind their elderly parents and younger siblings to find work in Nanyang2 and Hong Kong. They formed a group of early Chinese immigrants who helped lay the foundations for Chinese culture and community in Singapore.

In Singapore, the majie congregated mainly in Chinatown. Their lives, employment and recreational activities extended to the outskirts of Chinatown to include Keong Saik Road, Bukit Pasoh Road, Tanjong Pagar Road and Cantonment Road, as well as other parts of Singapore.

Many of these unmarried women were in their 20s. Once they arrived in Singapore, they banded together, forming a tight-knit group. They established clan associations, known as kongsi (公司), and pooled their resources to rent accommodations called kongsi fong (公司房). The women also took care of each other and depended on one another for moral, psychological and financial support. Those who arrived earlier would write letters to inform their friends and families back home about work opportunities in Singapore.

Many of these hardworking and independent majie took vows of celibacy, pledging to remain unmarried for life. This ceremonial vow included a ritual known as sor hei in Cantonese (梳起; literally “comb up”) that involved styling their hair into a neat bun at the back of their head. For the majie, this hairstyle became an expression of their social maturity and celibate status, in contrast to girly styles such as plaiting their hair into two braids. Once the majie reached her 40s, it was common to adopt young daughters so that she would have someone to depend on in her old age.

(Left) A majie. and her adopted daughter. Majie were Cantonese women from the Pearl River Delta region in China's Guangdong province, who journeyed to Southeast Asia in the 1930s to work mainly as domestic servants for wealthy families. Courtesy of Charmaine Leung.

(Left) A majie. and her adopted daughter. Majie were Cantonese women from the Pearl River Delta region in China's Guangdong province, who journeyed to Southeast Asia in the 1930s to work mainly as domestic servants for wealthy families. Courtesy of Charmaine Leung.{Right) Majie took vows of celibacy. Image shows a ritual called sor hei (梳起; literally “comb up”) in which the women styled their hair into a neat bun at the back of their head. Photo by Yip Cheong Fun. Courtesy of Andrew Yip.

My Foon Yee Por has since passed away and many of the majie known to my family are no longer around. Singapore probably has a handful of surviving majie left. Before long, they too will pass on. But they have certainly left behind many stories of old Keong Saik Road, and Foon Yee Por and her community form an indelible part of Singapore’s history and heritage today.

Wine, Women and Song

Keong Saik Road did not start off as a red-light district, although it was next to the notorious Smith Street, which was lined with brothels servicing workers and labourers.

Its beginnings were more wholesome. In the 1930s, many clan associations and wholesalers set up offices on Keong Saik Road. Because it was a place for business meetings and gatherings, there was a strong demand for post-meeting entertainment. This led to the birth of clan associations-cum-entertainment houses in the Keong Saik area which, in turn, saw the emergence of a culture where wealthy men indulged in food, alcohol, gambling, opium-smoking and entertainment by women.

Located on Keong Saik Road and Bukit Pasoh Road, the entertainment houses were premium set-ups aimed at the well-heeled. At these establishments, female singers and musicians, such as the pipa tsai (Cantonese for “little pipa player”),3 entertained men with song and music. Over time, this entertainment provided by such women led to the transformation of Keong Saik Road into a red-light district, complete with opium dens.

It was in the offices, clan associations and entertainment houses on Keong Saik Road that many majie found work as domestic helpers and cleaners. These early Chinese migrants brought with them many cultural and religious practices that are still being observed today such as “Beat the little people”.

Nestled among the shophouses is Zhun Ti Gong (or Cundhi Gong) – a Chinese temple dedicated to Guanyin, the Goddess of Mercy – located at 13 Keong Saik Road. An ornate structure with a roof featuring decorative beams and adorned with intricate motifs of dragons, peacocks, phoenixes and flowers, the temple has witnessed many sor hei ceremonies held by the majie.

Today, this temple is especially popular with former residents of Chinatown. While many of these elderly devotees have since moved to newer housing estates with their children, many still return with younger family members to offer their prayers on the first and 15th days of the lunar month.

The Zhun Ti Gong Temple (or Cundhi Gong) at 13 Keong Saik Road, 2000. Built in 1928, the temple played an important role in the lives of majie. Many of the sor hei ceremonies by the majie took place at the temple. Courtesy of Charmaine Leung.

The Zhun Ti Gong Temple (or Cundhi Gong) at 13 Keong Saik Road, 2000. Built in 1928, the temple played an important role in the lives of majie. Many of the sor hei ceremonies by the majie took place at the temple. Courtesy of Charmaine Leung.

The Indian Community

Apart from the predominantly Cantonese-speaking Chinese community who lived and worked on Keong Saik Road, a small community of Indians also called it their home.

Keong Saik Road was home to a shophouse occupied by Indian coolies. Many were young bachelors working in Singapore, but some were older men who had left their families in India in search of greener pastures in Singapore.

Devotees at the Sri Layan Sithi Vinayagar Temple welcoming the silver

chariot bearing Lord Murugan that has just arrived from the Sri Thendayuthapani Temple. The annual procession is called Punar Pusam and takes place the day before Thaipusam. Courtesy of the Chettiars’ Temple Society - Sri Thendayuthapani Temple.

Devotees at the Sri Layan Sithi Vinayagar Temple welcoming the silver

chariot bearing Lord Murugan that has just arrived from the Sri Thendayuthapani Temple. The annual procession is called Punar Pusam and takes place the day before Thaipusam. Courtesy of the Chettiars’ Temple Society - Sri Thendayuthapani Temple.

I remember an Indian man in his 30s living there who operated a “mama shop”4 just across the street. He spoke fluent Cantonese and always sold candy to kids at a discount, even giving them extra treats. He allowed children to hang around his shop, letting them admire the wide array of colourful merchandise that included toy swords, badminton rackets and magazines.

The shophouse where the Indian coolies lived was close to the Sri Layan Sithi Vinayagar Temple at 73 Keong Saik Road. During the Thaipusam festival that takes place between 14 January and 14 February each year, Keong Saik Road becomes a hive of activity. The Sri Layan Sithi Vinayagar Temple plays an important role in the run-up to Thaipusam. On the eve of the festival, at about 6 am, a silver chariot from the Sri Thendayuthapani Temple on Tank Road makes it way to the Sri Layan Sithi Vinayagar Temple during a procession known as Punar Pusam. The chariot bears Lord Murugan, the Hindu god of war, and it stays at the Sri Layan Sithi Vinayagar Temple until evening when the chariot and the procession return to the temple on Tank Road.5

| BEAT THE LITTLE PEOPLE |

| An interesting practice that was popular among the Chinese community of Keong Saik Road and Chinatown was to go to a wall near the Sri Layan Sithi Vinayagar Temple to “beat the little people” (打小人; da xiao ren in Mandarin). The term “little people” in the Chinese language is synonymous with evil people and negativity. |

| The ritual involved using either a clog or a shoe to repeatedly hit human-shaped paper figurines that symbolised the negativity in one’s life. An auspicious piece of red paper would be placed on top of the beaten figurines and the figurines pasted on the wall. Incense was then offered. |

| The Chinese believed that the ritual was effective in warding off evil and dispelling negativity in one’s life. It was commonly observed among the Cantonese communities of Hong Kong and Guangdong. It usually took place at road intersections, under bridges, and at the foot of a hill or mountain as these places were generally perceived to have bad fengshui and thus prone to the influence of evil spirits. |

|

| Women “beating the little people” on Keong Saik Road, 1950s. The Cantonese believe that the ritual would ward off evil and banish negativity in one’s life. In the background is the Sri Layan Sithi Vinayagar Temple before it was renovated into the current structure. Photo by Yip Cheong Fun. Courtesy of Andrew Yip. |

A Bustling Neighbourhood

In the 1970s and 1980s, the Keong Saik area also had businesses that co-existed with the brothels. Next to the Hindu temple was a seamstress whom the ladies of Keong Saik patronised to have their clothes tailored, while a nearby dentist looked after the dental health of residents.

Sim San Loke Hup Athletic Association was at No. 65, very close to the Indian dormitory. This was a place where young Chinese men learned and practised martial arts, and sometimes performed lion and dragon dances for the Keong Saik community during the Lunar New Year and other special occasions. The association is currently located at 85-B.

Besides the “mama shop”, there were two other provision shops on Keong Saik Road. One was situated across the road from the Indian dormitory, and the other was at the other end of the street, closer to Neil Road. There were no lack of options for dry provisions at Keong Saik, and residents only went to the wet markets of Chinatown to buy fresh produce.

At least two businesses provided specialised services for those who wanted to stay connected with China: a Chinese calligraphy shop offered letter-writing services for the illiterate who wanted to write home, and a sundries shop imported goods directly from China for those who yearned for special items and produce that were only available from their hometowns.

Located near Keong Saik Road was a factory called Yip Choy Sun (叶彩新), a family-run business that produced a variety of handmade paper boxes. It operated on the ground floor of 6 Jiak Chuan Road.6 The factory was busiest during the Mid-Autumn Festival when it produced thousands of boxes for Tai Chong Kok (大中国), a traditional bakery in Chinatown that was popular for its mooncakes. Yip Choy Sun operated at full capacity to meet the orders for mooncake boxes and because it was not uncommon to receive last-minute orders, the entire family would pitch in to get the orders out. The family moved out of the Keong Saik area when the patriarch passed away in October 1997.

A well-loved icon of Keong Saik Road, then and now, is the famous Tong Ah Eating House, formerly located in the distinctive red-and-white three-storey building situated on the triangular plot of land at the junction of Keong Saik and Teck Lim roads. The coffee shop was opened in 1939, the same year that the building was completed. Favoured by the residents of Keong Saik, Tong Ah was packed every morning. One of the most sought-after breakfast items was buttered toast topped with kaya.7

In 2013, the coffee shop moved across the street to number 35. The Chinese characters 東亞 (Tong Ah) remain inscribed on the facade of the former location. The kaya toast set – comprising buttered toast slathered with homemade kaya and paired with two soft-boiled eggs drizzled with soya sauce and a dash of pepper, all accompanied by hot coffee or tea – remains popular.

Keong Saik Road Today

To the uninitiated, Keong Saik Road may be just another street in Singapore. But for those who are interested in the history of our country, Keong Saik is part of Singapore’s heritage, offering a glimpse into the lives of early Chinese immigrants. The eclectic mix of communities and businesses at the Keong Saik Road of yesteryear has given the place a unique identity.

Shophouses on Keong Saik Road, 1997. Joanne

Lee Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Shophouses on Keong Saik Road, 1997. Joanne

Lee Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Keong Saik Road is now a trendy neighbourhood offering contemporary wine and dine options in restored shophouses, attracting many tourists who are often seen on the street posing for photographs. (Keong Saik’s international profile was raised after it was voted one of the top four travel sights in Asia by Lonely Planet in 2017). For me, Keong Saik Road is the first home I knew.

As I stroll along the Keong Saik area today, what I encounter now is very different from what I remember. On a recent visit, I walked past fancy restaurants and ultra-modern boutique hotels stylishly designed to attract a new generation of visitors. The community there is no longer the one I had been familiar with.

Although newness brings excitement, if we are not deliberate in preserving the spirit of our heritage beyond its physical structures, we may one day lose the intangible beauty of our past and heritage completely. I am grateful for the privilege to have lived in an iconic part of Singapore’s past and to have experienced the old Keong Saik Road and its community. As one of Singapore’s daughters, I can only hope that I have done my part in helping to preserve a little of Singapore’s heritage in my sharing about a street that was once my home.

|

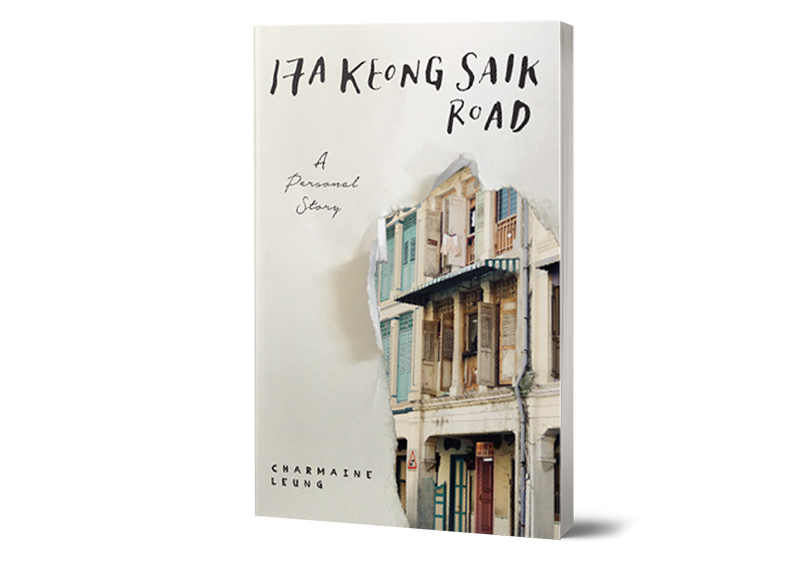

| Charmaine Leung grew up on Keong Saik Road in the 1970s and 80s as the daughter of a brothel operator. After having lived overseas for almost 20 years, Charmaine returned to Singapore and discovered a vastly different Keong Saik Road. |

| The unspoken family shame that shrouded much of her young life – and the changes she witnessed upon her return – prompted her to pen a memoir of her childhood years. |

| Leung’s book, 17A Keong Saik Road (2017) is available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries (Call nos.: RSING 959.57004951 LEU and SING 959.57004951 LEU) as well as for digital loan on nlb.overdrive.com. The book also retails at major bookshops and ethosbooks.com.sg. |

Charmaine Leung is the author of 17A Keong Saik Road, which was shortlisted for the Singapore Literature Prize in 2018. When she is not writing, Charmaine is a curious traveller who enjoys roaming the globe and seeking out off-the-beaten tracks to capture landscapes and communities through photography.

Charmaine Leung is the author of 17A Keong Saik Road, which was shortlisted for the Singapore Literature Prize in 2018. When she is not writing, Charmaine is a curious traveller who enjoys roaming the globe and seeking out off-the-beaten tracks to capture landscapes and communities through photography.

NOTES

-

See Loo, J. (2017, Oct–Dec). A lifetime of labour: Cantonese amahs in Singapore. BiblioAsia, 13 (3): 2–9. Retrieved from BiblioAsia website. ↩

-

Nanyang, which means “South Seas” in Mandarin, refers to Southeast Asia. ↩

-

The pipa, or Chinese lute, is a pear-shaped four-stringed musical instrument made of wood. Pipa tsai were girls trained to play various musical instruments and sing to entertain men in clubs and brothels in Singapore. In some instances, the girls were forced into prostitution. ↩

-

A “mama shop” or “mamak shop” (from Tamil word mama meaning “uncle” or “elder”) is a convenience store or sundry shop selling a wide variety of goods and provisions. ↩

-

The Punar Pusam procession takes place the day before Thaipusam, which is an annual festival dedicated to Lord Subramaniam, also known as Lord Murugan, the Hindu god of war. During Thaipusam in Singapore, devotees will carry a kavadi (which means “burden” or “load”) from the Sri Srinivasan Perumal Temple on Serangoon Road to the Sri Thendayuthapani Temple on Tank Road. For more information about Thaipusam, see National Library Board. (2016). Thaipusam written by Bonny Tan. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. For more information on Punar Pusam, see Ng, M. (2017, Oct–Dec). Micro India: The Chettiars of Market Street. BiblioAsia, 13 (3): 10–17. Retrieved from BiblioAsia website. ↩

-

Jiak Chuan Road – named after Tan Jiak Chuan, grandson of the philanthropist Tan Kim Seng – links Keong Saik Road to Teck Lim Road. It is home to several budget hotels and eateries today. The road was formerly part of the Keong Saik Road red-light district. ↩

-

Kaya is a type of jam made from coconut, eggs and sugar, and is typically spread on toast. It is popular in Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia. ↩