The King’s Chinese: The Life of Sir Song Ong Siang

Song Ong Siang was the first local-born barrister and the first person in Malaya to receive a knighthood. Kevin Y.L. Tan recounts the extraordinary life of this Peranakan luminary.

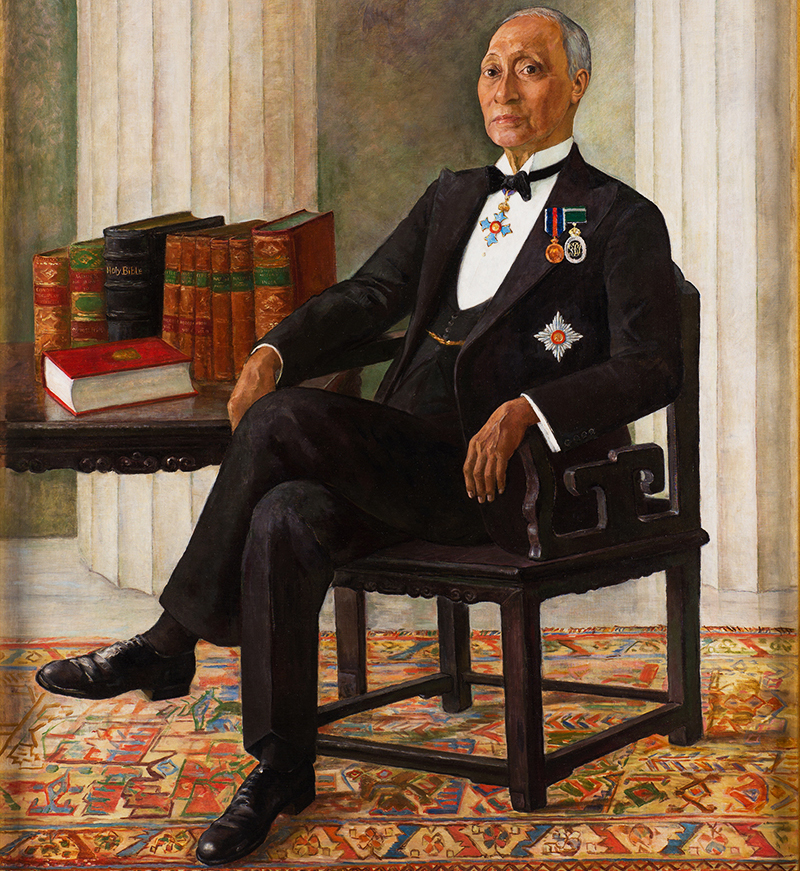

A painting of Song Ong Siang by J. Wentscher, 1936. Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

A painting of Song Ong Siang by J. Wentscher, 1936. Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

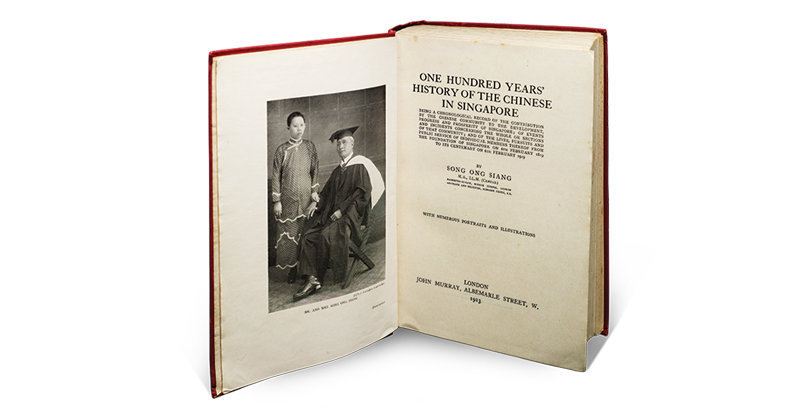

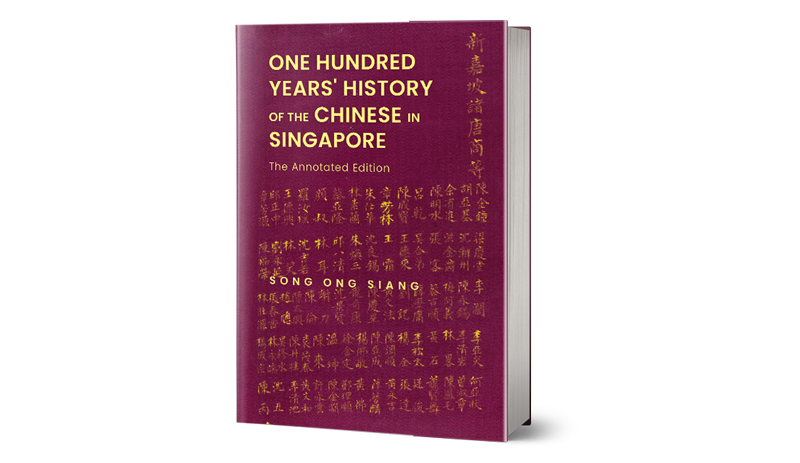

Ever since it was first published in 1923, Song Ong Siang’s (1871–1941) One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore1 has been the standard reference text on some of Singapore’s early Chinese personalities and their contributions. Although containing a number of errors and not academically referenced with footnotes, the book is nevertheless used as a primary source of information and was reprinted in facsimile form twice, in 1967 and 1984.2 Although now almost 100 years old, the book is important enough that an annotated version was published online in 2016 and in print earlier this year by the National Library Board and World Scientific Publishing.

Given its significance, it is remarkable to think that if not for a series of events, this book might never have come into being at all: Song was not the person originally identified to write the book; in fact, it was not meant to be a book in the first place but a small part of a larger book. And even after completing all the research and writing – an effort that took more than three years – financial issues threatened to scuttle its publication. Fortunately, all the obstacles were eventually overcome, and the book finally saw light of day – much later than planned, much longer than expected but much richer than it would have been otherwise.

One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore sprang from an effort to commemorate the centenary of Singapore’s founding with a book. The editors of what would be a two-volume anthology entitled One Hundred Years of Singapore3 originally thought that the book should have two or three chapters on the history of the Chinese in Singapore and that these chapters should be written by a Chinese.4 They had initially approached Dr Lim Boon Keng, but he was too busy and recommended Song instead.

The title page of Song Ong Siang’s One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore (1923). The frontispiece features a photo of Song and his wife, Helen Yeo Hee Neo, after he was conferred the Knight Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (KBE) in 1936. The photo was taken by Hills & Saunders in Cambridge during their European vacation. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession no.: B20048226B).

The title page of Song Ong Siang’s One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore (1923). The frontispiece features a photo of Song and his wife, Helen Yeo Hee Neo, after he was conferred the Knight Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (KBE) in 1936. The photo was taken by Hills & Saunders in Cambridge during their European vacation. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession no.: B20048226B).

No sooner had Song embarked on the work when he realised “the futility of attempting to write a historical review or a general survey of the subject which would be of any real value to the readers”. 5 It was like, as Song said, “trying to make bricks without straw” and he decided that he would instead “compile a chronological history of the Chinese in Singapore”, along the lines of Charles Burton Buckley’s An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore published in 1902.6

Song saw himself as a compiler rather than an author. “I do not claim originality,” he wrote. His aim, he said, was “to be just a faithful recorder” of events. The work involved in writing this book took Song and his two research assistants over three years. They were also assisted by members of the Straits Chinese Reading Club – especially Lim Seng Kiang, Tay Ah Bee, Cheang Peng Moh, Tan Kim Moh and Lee Peng Yam – who devoted “their Saturday afternoons, for many months, at the Raffles Library, poring over” back issues of local English-language newspapers.7

In addition to scouring old newspapers, Song also asked a number of individuals – most notably William Makepeace, John Anderson (of Guthrie & Co), and the Reverends J.A. Bethune Cook and William Murray – to provide character sketches of individuals to be featured in the book.

The two-volume One Hundred Years of Singapore was published by John Murray of London in 1921, but at the time, Song’s book was not ready. It was only in September 1922, while on holiday in Europe,8 that Song went to England to persuade the publisher John Murray to publish his manuscript. As Song was unable to underwrite the cost, he tried to fund its publication through subscriptions. However, the response was poor and Song wrote to inform Reverend William Murray, one of his assistants, that there was a likelihood the book would not be published.9

Murray then penned an open letter to the editor of The Straits Times, urging him to make the book a reality. It is not clear what happened after this but the book was eventually published by November 1923.10 Each copy was sold for $12, which was more than a month’s wages for most Chinese in Singapore at the time.

The Singapore Free Press published a long, glowing review of the book and opined that every “European house of business should possess a copy”. It added, rather presciently, that it would make a “unique gift” to “the present generation of Chinese and to generations yet to be born”. 11 A review in the Birmingham Post – republished in The Singapore Free Press in January 1924 – was less laudatory, calling the book “not so much history as the raw material for history”.12

For a “compilation” of this scale – focused as it was on the elite, wealthy, English-educated Straits Chinese community13 – the book has survived remarkably well. As historian Paul Wheatley noted in his review of the 1969 reprint, the book is about affluent Chinese with similar backgrounds to Song’s, and “there is practically nothing about the tens of thousands of coolies who pulled the rickshas, laboured in the gambier bangsals, worked on building construction, or served in the shops in Singapore”.14

That said, social historian James Warren noted that while one had to search through the index carefully “for the fragments of the life stories of ‘faceless’ coolies who did the difficult [and] dirty work of building and binding a nation”, Song nonetheless “encyclopaedically records more information about ordinary Chinese in Singapore than most earlier works in Chinese”.15

In 2016, I completed an annotated e-book version of this work,16 which was subsequently released in print in March this year. As Song did not offer detailed references to his sources in his book, the annotations attempted to trace the sources Song used and reference them for the modern reader. With the help of two other editors and a team of researchers, we verified facts, especially dates and details, and made notes of discrepancies and errors, all of which are recorded in the footnotes. These annotations will hopefully enhance the book’s value as a research tool and reference work for future generations of researchers and readers.

An Unconventional Prelude

If all that Song had achieved was to produce this seminal work, his reputation would be secure. But Song was much more than just the compiler of One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore. He was a man of great talent and intelligence – the first local-born barrister and lawyer, and the first person in Malaya to be knighted. Song was also a prominent leader of the Straits Chinese community and the Presbyterian Church on Prinsep Street.

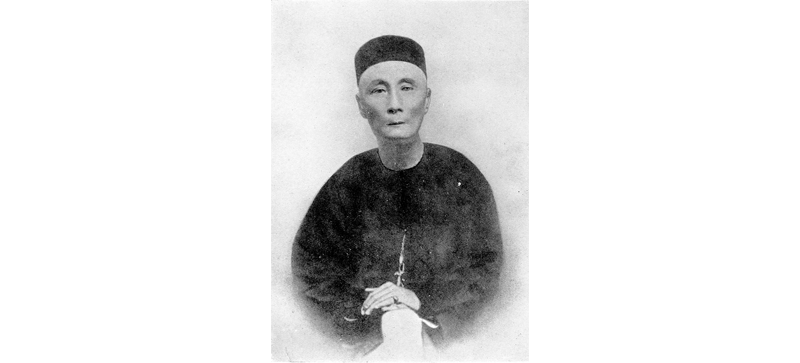

Although we do not know when Song’s forebears first arrived in Malaya from Fujian province in China,17 Walter Makepeace, who wrote the foreword to Song’s book, mentioned that Song was a fifth-generation Straits Chinese.18 Song’s father, Song Hoot Kiam, was born in 1830 and had studied in Melaka, Singapore and Hong Kong before receiving an education in Scotland where the plan was to groom him to become a missionary who would later serve in China.

Song Hoot Kiam, father of Song Ong Siang. Hoot Kiam Road in Singapore is named after him. Image reproduced from Song, O.S. (1923). One Hundred Years' History of the Chinese in Singapore (p. 78). London: John Murray. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession no.: B20048226B).

Song Hoot Kiam, father of Song Ong Siang. Hoot Kiam Road in Singapore is named after him. Image reproduced from Song, O.S. (1923). One Hundred Years' History of the Chinese in Singapore (p. 78). London: John Murray. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession no.: B20048226B).

This was not to be. On returning to Singapore in 1849, Hoot Kiam briefly joined the Singapore Institution Free School (later Raffles Institution), and then became a cashier with the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company (P&O) for 42 years until his retirement in 1895. In 1870, upon the death of his first wife, Hoot Kiam, then 40, married Phan Fung Lean, who hailed from a Christian family in Penang. Their first child, Song Ong Siang, was born on 14 June 1871. Song had at least one elder half-brother, Song Ong Boo, from his father’s first marriage, of which practically nothing is known, and a younger brother, Song Ong Joo. In 1878, Song entered Raffles Institution (RI),19 which, at the time, provided both primary and secondary education.

When he was 12, Song was awarded the Guthrie Scholarship – given out to the top Chinese pupil of the year, the Dux (or leader) – for the first time in 1883. In all, he won the scholarship a record five times at RI. Beyond his academic talents, Song’s leadership abilities were apparent and he was made Head Boy (or Head Prefect) in 1886.20

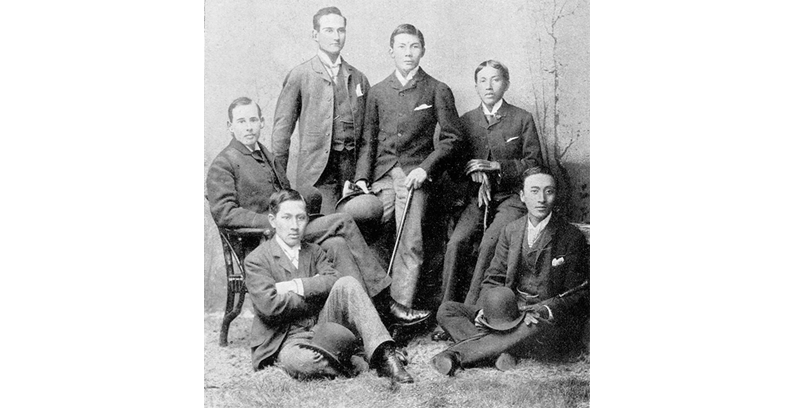

That year, when he was just 15, Song sat for the High Scholarship examination. This scholarship (renamed the Queen’s Scholarship in 1890) had been initiated by Cecil Clementi Smith, Governor of the Straits Settlements, who held the view that promising local boys be given the opportunity to complete their studies in England. Smith persuaded the government to set aside £400 annually for two Higher Scholarships.

A group of Queen’s Scholars. Back row from left: James Aitken (1886), Charles Spence Angus (1886), P.V.S. Locke (1887) and Dunstan Alfred Aeria (1888). Seated on the ground: Lim Boon Keng on the left (1887) and Song Ong Siang on the right (1888). Photo by the Straits Photographic Studio in Singapore. Image reproduced from Song, O.S. (1923). One Hundred Years' History of the Chinese in Singapore (p. 224). London: John Murray. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession no.: B20048226B).

A group of Queen’s Scholars. Back row from left: James Aitken (1886), Charles Spence Angus (1886), P.V.S. Locke (1887) and Dunstan Alfred Aeria (1888). Seated on the ground: Lim Boon Keng on the left (1887) and Song Ong Siang on the right (1888). Photo by the Straits Photographic Studio in Singapore. Image reproduced from Song, O.S. (1923). One Hundred Years' History of the Chinese in Singapore (p. 224). London: John Murray. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession no.: B20048226B).

Song topped the list of examinees while J.A. dos Remedios came in second, followed by Charles Spence Angus and James Aitken. Song and dos Remedios were disqualified as Song was underaged and dos Remedios was not a British subject by birth. Instead, Angus and Aitken – both also RI students – were awarded the scholarship. Song and dos Remedios did, however, win the Local Government Scholarships of $180 and $120 respectively in 1886. 21

A year later, Song topped the cohort yet again but was again disqualified for being underaged since he was not yet 16 at the time of the examination. In 1888, Song topped the examination a third time and was finally awarded the scholarship. He had initially wanted to study medicine as he was much impressed and inspired by Lim Boon Keng’s accounts of life as a medical undergraduate at the University of Edinburgh (Lim had been awarded the scholarship in 1887, in place of the disqualified Song).

However, Song changed his mind after reading about the exploits of Chan-Toon, the brilliant Burmese law student who bagged all eight principal prizes at Middle Temple. With his £200 scholarship money, Song headed for Middle Temple in London. Right up to the 20th century, one could qualify as a lawyer without a university degree. All an aspiring student needed was to read at one of the four Inns of Court22 and pass the Bar examinations. This was precisely what Song planned to do.

After arriving in England in 1888, Song met up with his former RI principal, Richmond William Hullett, who arranged for an old friend, W. Douglas Edwards – a property law expert – to tutor Song for a fee of five guineas23 a month. This fee came out of Song’s monthly allowance of just over £16. As Song had to pay tax on his scholarship and remit £5 a month to the Crown Agents who provided the advance of £150 for his Middle Temple entrance fee, he was left with very little to live on. Relief came from the first prize of 100 guineas that he had won in 1889 for Constitutional Law and Private International Law at Middle Temple. A year later, he won another 100 guinea-prize for Jurisprudence and Roman Law.

With these additional funds, Song decided he could read for a law degree and enrolled at Downing College at the University of Cambridge in 1890. There, he received an honourable mention in the Whewell Scholarship competition in International Law and topped the Second Class of Part I of the Law Tripos in 1892.

But Song won no further prizes after this and his financial position became precarious. His former RI schoolmate, Robert Frederick McNair Scott, urged his father, Thomas Scott (of Guthrie & Co), to provide Song with some financial assistance. In June 1893, Song graduated with Second Class in Part II of the Law Tripos, and in the same month was called to the English Bar at Middle Temple.24

Return to the Colony

Song returned to Singapore in October 1893 and immediately became active in the local scene. Like his father, Song worshipped regularly at the Straits Chinese Presbyterian Church (the former Malay Chapel; present-day Prinsep Street Presbyterian Church) and soon took on the role of a voluntary preacher. At the end of 1893, the 22-year-old Song was elected President of the Chinese Christian Association which his father Hoot Kiam had founded in 1889.25 Song served in this capacity until his death almost 50 years later.

Members of Prinsep Street Church, c. 1920s. Song Ong Siang is in a dark jacket in the middle of the front row (with his wife on his right). Prinsep Street Presbyterian Church Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Members of Prinsep Street Church, c. 1920s. Song Ong Siang is in a dark jacket in the middle of the front row (with his wife on his right). Prinsep Street Presbyterian Church Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Song was later appointed Secretary of the Deacons’ Court and succeeded his father as one of the church’s three Elders when Hoot Kiam passed away on 7 October 1900.26 Between 1908 and 1916, Song also edited the church’s monthly magazine, Prinsep Street Church Messenger.27 Song preached regularly in Malay and was a much-loved and honoured member of the church.

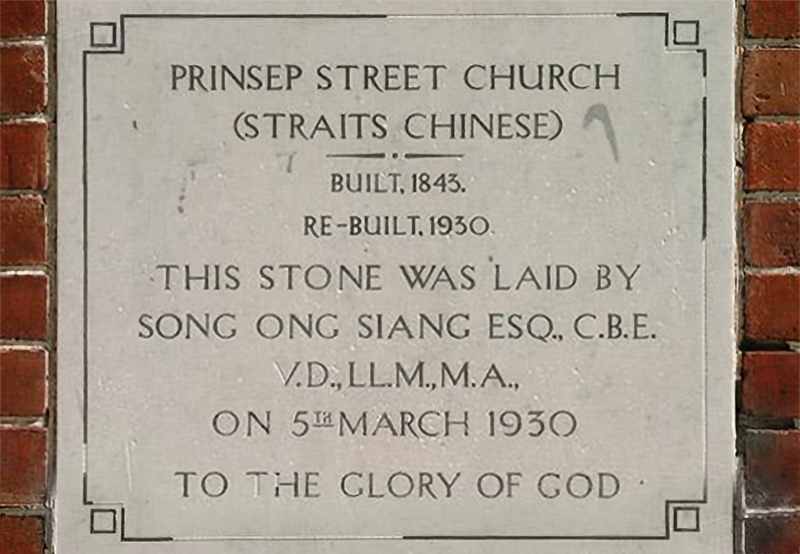

In March 1930, Song laid the foundation stone for the church’s new building, which opened in February 1931.28 He served the church faithfully and conducted services until a few months before his death in 1941.

The plaque mounted on the facade of the Prinsep Street church states that the foundation stone was laid by Song Ong Siang on 5 March 1930. Like his father, Song was a much-loved and honoured member of the church. Today, the church is known as the Prinsep Street Presbyterian Church. National Library Board, Singapore.

The plaque mounted on the facade of the Prinsep Street church states that the foundation stone was laid by Song Ong Siang on 5 March 1930. Like his father, Song was a much-loved and honoured member of the church. Today, the church is known as the Prinsep Street Presbyterian Church. National Library Board, Singapore.

The Prinsep Street Presbyterian Church with its distinctive red-brick facade and a sloping roof with a belfry at the front, 2003. The church was previously known as the Straits Chinese Church. National Library Board, Singapore.

The Prinsep Street Presbyterian Church with its distinctive red-brick facade and a sloping roof with a belfry at the front, 2003. The church was previously known as the Straits Chinese Church. National Library Board, Singapore.

His Life as a Lawyer

On 20 March 1894, William John Napier, who later became Attorney-General of the Straits Settlements, moved a petition for Song to be called to the Singapore Bar. One week later, Song was admitted to the Singapore Bar, the first Chinese barrister to do so.29

Song reconnected with his former Raffles classmate, James Aitken, and together they established the law firm of Aitken & Ong Siang.30 It was a successful partnership, and both senior partners appeared regularly in court representing clients in all sorts of cases, including criminal matters. It appears that much of Song’s own practice concerned Chancery work (which deals with trusts, probate, real property and tax).31

On top of his work at the law firm, Song was also Assistant Editor of the Straits Settlements Law Reports from 1894 to 1899.

During Aitken’s absence from Singapore between 1914 and 1919, Song ran Aitken & Ong Siang single-handedly.32 Following Aitken’s death in 1928, Song became the doyen of the Singapore Bar. When he died in September 1941, his wife petitioned to appoint C.H. Koh as receiver and manager to carry on the affairs of the firm until the end of 1941 when the firm was dissolved.33

Advancing Singapore’s Straits Chinese Community

Beyond his legal and church work, Song was active in many other civic organisations and causes. In July 1894, Song and his brother-in-law Tan Boon Chin started a daily newspaper in Romanised Malay called Bintang Timor (“Star of the East”). Unfortunately, this enterprise ran into financial difficulties and lasted less than a year.34

Undaunted, Song teamed up with Lim Boon Keng to start The Straits Chinese Magazine: A Quarterly Journal of Oriental and Occidental Culture in March 1897; the inaugural issue sold 800 copies.35 This was the first English-language magazine published by the Straits-born and targeted at the educated Straits-born community who needed “a medium for the discussion of political, social and other matters affecting the Straits people generally”.36 The magazine was in circulation until December 1907 when it folded due to the “lack of financial support”.37

Song, Lim Boon Keng and two other senior Straits Chinese notables – Tan Jiak Kim and Seah Liang Seah – founded the Straits Chinese British Association (SCBA; predecessor of today’s Peranakan Association) on 17 August 1900. Tan Jiak Kim was elected the first President of the association, with Song as Secretary.38 By establishing the SCBA, the Straits Chinese would now have a voice as they demonstrated their loyalty to the British Crown. Thus they became known as the “King’s Chinese”, distinct from the rest of their Chinese kin in their dress, language and attitudes.

Song also helped establish the first Chinese Company of the Singapore Volunteer Infantry in November 1901 and was appointed Sergeant of B Company. In August 1902, he was among the seven volunteers selected to represent the Company in the Straits Contingent at the coronation of King Edward VII in London. Song eventually rose to the rank of Captain.39

During World War I, Song mobilised Chinese volunteers “to do Guard duty at various strategical posts on the island”.40 For his services in the Volunteer Infantry, Song was awarded the Volunteer Long Service Medal in 1922 and the Volunteer Officer’s Decoration in 1924.

Song was also a strong advocate of the welfare of women in Singapore. Through his influence as a member of the 1926 Chinese Marriage Committee, he pushed for reforms that resulted in the Civil Marriage Ordinance of 1941 which imposed monogamy on non-Muslim marriages registered under the law.41 He also founded the Singapore Chinese Girls’ School in 1899 with Lim Boon Keng and other prominent Chinese leaders.42

In November 1919, Song was appointed Acting Chinese Unofficial Member of the Straits Settlements Legislative Council for two months, and then again from February to August 1921. When Lim Boon Keng left Singapore for China in October 1921 to become the President of Amoy University, Song replaced him as Unofficial Member of the Legislative Council. Except for a two-year break, Song held this post until his retirement in October 1927.43

Other Public Contributions

Song was also President of the Straits Chinese Literary Association and the Old Boys’ Association of Raffles Institution, as well as Honorary Member of the Rotary Club.

He also served on the Raffles Museum and Library Committee and the Governor’s Straits Chinese Consultative Committee. He was instrumental in establishing the Hullett Memento Fund44 and the Hullett Memorial Library at Raffles Institution (in honour of his former school principal) and in setting up the Friends of Singapore Society.45 He was elected as president of the latter and remained in office until his death in 1941.

For his public service and contributions, Song was made Knight Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire in August 1936, the first Singapore-born person to be knighted.46

Song’s Personal Life

On 29 September 1907, when Song was 36 years old, he married Helen Yeo Hee Neo (the second daughter of Yeo Poon Seng, a well-known sawmill owner), who was 16 years his junior.47 It was an arranged marriage and the first Chinese military wedding to be held in the Straits Settlements. The couple had no children of their own but adopted three daughters.48 While his father Hoot Kiam lived in the heart of town, at 60 North Bridge Road, Song and his family lived at 322 East Coast Road in Katong, the favoured hub of wealthy Straits Chinese families.

After a brief illness, Song died at home on 29 September 1941 at the age of 70. The funerary church service was conducted by Reverend T. Campbell Gibson at Song’s beloved Straits Chinese Presbyterian Church on Prinsep Street. The Union Jack-draped coffin was then placed on a gun carriage and conveyed to Bidadari Cemetery where officers and non-commissioned officers of the Chinese Company formed the guard-of-honour. Three volleys were fired and six regimental buglers sounded the last post.49

|

| One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore: The Annotated Edition is available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries (Call nos.: RSING 959.27 SON-[HIS] and SING 959.57 SON-[HIS]). The book also retails at major bookshops in Singapore. |

Dr Kevin Y.L. Tan is Adjunct Professor at the Faculty of Law, National University of Singapore, and at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University. He specialises in Constitutional and Administrative Law, International Law and International Human Rights. He has written and edited over 50 books on the law, history and politics of Singapore.

NOTES

-

Song, O.S. (1923). One hundred years’ history of the Chinese in Singapore. London: John Murray. (Accession no.: B02956336A) [Note: For the purposes of this article, references to Song’s classic book will be to the original version.] ↩

-

The first reprint was by the University of Malaya Press in 1967. The second facsimile reprint was undertaken by Oxford University Press in 1984. ↩

-

Although the book was meant to commemorate Singapore’s centenary in 1919, it was only published two years later in 1921. See Makepeace, W., Brooke, G.E., & Braddell, R.S.J. (Eds.) (1921). One hundred years of Singapore: Being some account of the capital of the Straits Settlements from its foundation by Sir Stamford Raffles on the 6th February 1819 to the 6th February 1919 (Vols. I and II). London: John Murray. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.51 MAK) ↩

-

Song, 1923, p. ix; See Buckley, C.B. (1902). An anecdotal history of old times in Singapore: From the foundation of the settlement under the honourable the East India Company, on February 6th, 1819, to the transfer of the Colonial Office as part of the colonial possessions of the Crown on April 1st, 1867 (Vols. I and II). Singapore: Fraser & Neave. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.57 BUC) ↩

-

Song Ong Siang and his wife Helen embarked on a 10-month extended holiday in Europe on 24 March 1922, returning only on 25 January 1923. Accompanying them were Helen’s sister and her husband, Tan Soo Bin. During their trip, the Songs wrote many postcards to family members back in Singapore. In 2017, Dorothy and Joyce Tan donated a collection of 43 postcards to the National Library Board in memory of their father, Tan Kek Tiam. Tan was married to Song Siew Lian, the adopted daughter of Mr and Mrs Song Ong Siang. See Ong, E.C. (2017, Oct–Dec). Mr Song’s European Escapade. BiblioAsia, 13 (3). Retrieved from BiblioAsia website. ↩

-

Murray, W. (1922, October 11). History of the Chinese community. The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Chinese in Singapore. (1923, November 23). The Malaya Tribune, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Chinese in Singapore. (1923, November 27). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The review is reproduced in The Chinese in Singapore. (1924, January 16). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (Weekly), p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The term “Straits Chinese” refers to the Malayan-born Chinese of the 19th and early 20th centuries. They are also called Peranakan Chinese or Baba, although the latter term refers mainly to Peranakan men. Peranakan women are called nonya. During the colonial era, the Straits Chinese were also known as the King’s Chinese in reference to their status as British subjects after the Straits Settlements became a Crown colony in 1867. The Peranakans speak a version of Malay, called Baba Malay, which has borrowed many Hokkien words and phrases. Their cuisine also reflect Malay influences. See National Library Board. (August 26, 2013). Peranakan (Straits Chinese) community written by Jaime Koh. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia. ↩

-

Wheatley, P. (1969, February). Book review: One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore. The Journal of Asian Studies, 28 (2), 402–403, p. 403. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Warren, J. (1985, December). Book review: One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore. The American Historical Review, 90 (5), 1259–1260, p. 1260. Retrieved from Oxford University Press website. ↩

-

Song, O.S. (2016). One hundred years’ history of the Chinese in Singapore: The annotated edition (annotated by Kevin Y. L. Tan). Singapore: National Library Board. ↩

-

According to Lee Guan Kin, Song’s ancestry can be traced to Nanjing county in Fujian. See Lee, G.K. (2012). Song Ong Siang (p. 1009). In L. Suryadinata (Ed.), Southeast Asian personalities of Chinese descent: A biographical dictionary (Vol. 1, pp. 1008–1100). Singapore: Chinese Heritage Centre & Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSING 959.004951 SOU) ↩

-

Raffles Institution. (1886, December 23). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Notes. (1886, October 16). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The four inns of Court are Middle Temple, Inner Temple, Gray’s Inn and Lincoln’s Inn. To be called to the English Bar and practise as a barrister in England and Wales, a person must belong to one of these inns. ↩

-

At the time, a guinea was equivalent to 1 pound and 1 shilling; 20 shillings made up a pound. ↩

-

Chinese Christian Association. (1893, September 9). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Death. (1900, October 8). The Straits Times, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Untitled. (1930, March 3). The Malaya Tribune, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Roll of Advocates and Solicitors Singapore: 1852–1968 (Supreme Court Library, Singapore). ↩

-

‘Knight without fear & without reproach’. Morning Tribune, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Untitled. (1941, October 2). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Trocki, C.A. (2006). Singapore: Wealth, power and the culture of control (p. 60). London; New York: Routledge. (Call no.: RSING 959.5705 TRO-[HIS]) ↩

-

The National Library of Singapore holds the complete 11 volumes of the magazine, which was published four times a year – in March, June, September and December. ↩

-

The “Straits Chinese Magazine”. (1897, March 31). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Straits Chinese British Association. (1900, August 18). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

“One of greatest Straits Chinese”. (1941, September 30). The Straits Times, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore Chinese Girls’ School. (1899, April 24). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Sir Ong Siang Song dies. (1941, September 29). Morning Tribune, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Presentation to Mr Hullett. (1906, September 28). Eastern Daily Mail and Straits Morning Advertiser, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

“Friends of Singapore” Society. (1937, June 29). Morning Tribune, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Long and brilliant career of Sir Ong Siang Song. (1936, August 25). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 9; Malaya’s first Chinese knight. (1936, January 5). Sunday Tribune (Singapore), p. 2; Mr Small’s address. (1936, August 25). Morning Tribune, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Song, O.S. (1984). One hundred years’ history of the Chinese in Singapore (p. xi). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 SON-[HIS]) ↩

-

Funeral service. (1941, October 1). The Morning Tribune, p. 15. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩