Leprosy: A Story of Suffering,

But Also of Hope

People struck with leprosy were shunned and forced to live in isolation at the Trafalgar Home in Yio Chu Kang. Danielle Lim tracks the history of this disfiguring disease in Singapore.

Minister for Health Yong Nyuk Lin (second from left) visiting Trafalgar Home and interacting with residents, 1964. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Minister for Health Yong Nyuk Lin (second from left) visiting Trafalgar Home and interacting with residents, 1964. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Leprosy is a disease that has perhaps left the longest trail of illness and suffering in human history. The disease is mentioned in an ancient Chinese medical treatise, Neijing (内经; Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine), as early as 250 BCE.1 Leprosy is the result of an infection caused by the bacteria Mycobacterium leprae. It is a chronic, infectious, disfiguring disease that has historically caused its sufferers to be shunned by society. Known and feared for thousands of years, it was only in the late 1940s that a cure for the disease became available.

According to estimates by the World Health Organization, there were around 10 to 12 million leprosy cases globally between the mid-1960s and the mid-1980s.2 In 2010, the number of new cases dropped to 228,474.3 What is not known, however, is the cumulative total number of people who have suffered leprosy’s chronic course of incurable disfigurement and social exile over the centuries.

In Singapore, a total of 8,500 leprosy patients were registered between 1951 and 1995.4 Here, as in other parts of the world, leprosy carries a social stigma. Those who contracted the disease were ostracised by family and friends and banished from society. They lived as outcasts, people whom the community feared. It was only after a cure was discovered that sufferers could return to society, though not all of them chose to.

The segregation of leprosy sufferers in colonies and asylums was a common worldwide practice. In July 1897, the Lepers’ Ordinance was passed in the Straits Settlements empowering the authorities to detain leprosy sufferers indefinitely in asylums in order to prevent the spread of the disease.5 Prior to this, there was no law requiring compulsory segregation.

In the early 1900s, male lepers in Singapore were housed in rudimentary leprosariums in the city fringes and beyond, while females were warded in Kandang Kerbau Hospital. It was only in 1918 that a dedicated camp for male patients was established on McNair Road. In 1926, a small centre with four wards for female patients was constructed on the Trafalgar rubber estate off Yio Chu Kang Road. Four years later, a new male camp was built adjacent to the centre for females, and both sites became known collectively as the Singapore Leper Asylum.

Up to the 1920s, inmates of the asylum had to wear uniforms bearing the letter “L”. In the 1930s, the asylum’s gates were manned by security guards armed with rifles to prevent residents from escaping and infecting the rest of the population. The asylum was renamed Trafalgar Home in 1950.6

Trafalgar Home

In mid-20th century Singapore, there were three diseases known as the “three brothers”. Mental illness was considered the mildest and hence the little brother while tuberculosis was known as the second brother. The most feared was leprosy, known as the eldest brother.

So intense was the fear of leprosy that it was common for public buses to drive past the bus stop nearest to Trafalgar Home without stopping to pick up those waiting there. Nurses working at the home had to walk to the next bus stop to get a ride home.

It was no coincidence that Trafalgar Home was situated in a remote area in Yio Chu Kang, beside the old Woodbridge Hospital for patients with mental illnesses. With its high walls and barbed wire, the home could easily be mistaken for a prison.

Trafalgar Home in Yio Chu Kang – which was shuttered in 1993 – was surrounded by high walls and barbed wire to prevent residents from escaping. Courtesy of Loh Kah Seng.

Trafalgar Home in Yio Chu Kang – which was shuttered in 1993 – was surrounded by high walls and barbed wire to prevent residents from escaping. Courtesy of Loh Kah Seng.

Upon entering, one would encounter the home’s general office. Behind the office was the occupational therapy room where residents wove baskets and made items such as handbags and clothes, some of which were sold. Further inside was the female infirmary, followed by the community hall and then the male infirmary. The girls’ dormitory was above the female infirmary; similarly, the male dormitory was located above the male infirmary. There was also a chapel on the grounds.

Trafalgar Home was based on the concept of an “open village” with room for expansion. More than 60 semi-detached cottages, which could accommodate two adults each, were built on one end of the compound on the same side as the female infirmary. Each cottage had a kitchen, two cupboards, two bedside lockers and two beds. At one point, Trafalgar’s grounds occupied some 125 acres.7

The semi-detached cottages on the grounds of Trafalgar Home, 1952. Housing two adults, each unit was equipped with a kitchen, two cupboards, two bedside lockers and two beds. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The semi-detached cottages on the grounds of Trafalgar Home, 1952. Housing two adults, each unit was equipped with a kitchen, two cupboards, two bedside lockers and two beds. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Before World War II, nursing duties were performed mainly by the residents themselves as professional medical and nursing staff were reluctant to work in leprosariums. From the end of the Japanese Occupation until the mid-1960s, the Roman Catholic nuns of the Franciscan Missionaries of the Divine Motherhood (FMDM) order carried out most of the nursing duties at Trafalgar Home.

When the nuns left, they were replaced by local female nurses, many of whom approached their duties with dread and trepidation. One of the nurses admitted that when she was offered food prepared by the residents, she was so scared that she did not dare eat it. Another said she would immediately soak her clothes in Dettol when she returned home from work.8 As with other leper asylums throughout the world, the residents were mindful of such fears; they kept a respectful distance from healthy people and refrained from physical contact.

The home’s able-bodied residents worked and contributed to the daily running of the home as patient-workers. Some trained as nursing aides or hospital attendants, assisting in the medical care of fellow patients, while others became teaching aides and helped out at the school within the grounds. Others handled the cooking chores in the kitchen, did the laundry, carried out clerical duties in the office and wove baskets in the occupational therapy room. Such tasks made the residents feel useful and also enabled them to earn a small allowance.

Residents of Trafalgar Home weaving baskets and other items in the occupational therapy room, 1963. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Residents of Trafalgar Home weaving baskets and other items in the occupational therapy room, 1963. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A small farm on the grounds allowed residents to grow vegetables to supplement their rations. Social gatherings such as club nights on Fridays were organised, during which treats of orange juice were eagerly anticipated. At these activities, friendships were formed and occasionally love blossomed. At times, fights broke out, especially when gambling and alcohol consumption had taken place. For the children of Trafalgar Home, the highlight was the annual Christmas party. Residents were also involved in sports and participated in extra-curricular groups such as Boy Scouts and Girl Guides.

Because Mycobacterium leprae attacks the nerves and muscles, many patients suffered intense pain as the disease progressed. Steroids such as prednisolone relieved the pain, but these were prescribed very sparingly by doctors who were only too aware of the dangers of steroid addiction. Some patients would obtain the medication and sell it to other patients who were in great pain and desperate for relief.

| LIVING WITH LEPROSY |

| Here are firsthand accounts from former residents of Trafalgar Home as well as a nurse and a social worker. |

| This hand began to be clawed… |

| “My body was aching but I still went to work… After it passed, I had to endure a bit, and after a long time, it would be over. I also didn’t take medicine. But my hands began to have red patches. Red, like it has been scalded by boiling water… when the day was very hot, my body felt very cold… very slowly, this hand began to be clawed, every day the joints couldn’t flex.”9 |

| Tan Teow Meng ignored the initial signs of the disease and worked as a coffee shop assistant until he was admitted to Trafalgar Home in 1974, where he was a resident for about 20 years. |

| I think of myself as a living death |

| “No visitors were allowed to come in. It was surrounded by walls. I was just like a prisoner… I felt very sad, and I thought that there is no medicine to cure us… I think of myself as a living death, surrounded by walls and kept inside, with no medicine.”10 |

| Joseph Tan was admitted into the Singapore Leper Asylum (later renamed Trafalgar Home) in 1933 at the age of 11. |

| After a long time… your flesh becomes like metal |

| “The injection was on the arm or sometimes on my buttock. The needle was thick but when it went in, it got bent. After many injections, the skin there became like metal. The needle became bent like a snake. Every week, there were three injections. After the injection, the medicine remained in the arm and couldn’t diffuse. It was not watery, it was like milk. It was thick like white milk. After a long time, month, years, your flesh becomes like metal.”11 |

| Kuang Wee Kee was admitted into Trafalgar Home in 1949 when he was 19 years old. The Japanese Occupation had deprived him of the opportunity to seek immediate treatment. |

| The rotten sweet potato spoils the yam |

| “One person got leprosy and people will be afraid of the whole family. They said that you all have this horrible disease. Right? They may not show it openly but they will be afraid in their heart. You understand? The person will suffer. My brothers and sisters will also suffer… It was like that. We didn’t do anything. The rotten sweet potato spoils the yam. You understand? The sweet potato is rotten, the yam is not rotten, but because of the sweet potato, the yam will also be affected.”12 |

| Kuang Wee Kee. |

| If you took the bus, people would complain |

| “Some of them had ulcers and they wore bandages. Last time, many people complained about them. You couldn’t blame the bus [driver] for not allowing you to board. When the bus conductor saw you like this, he would ask you to wait for the next bus. It was not that they didn’t want to take you. If you took the bus, people would complain to the bus company. They told the bus conductor to tell you to take the next bus. So you… understand… [why] they didn’t want you to take the bus.”13 |

| Kuang Wee Kee. |

| Tell them she has gone to Penang |

| “I was in charge of the youth club in Trafalgar… the mother came crying with the child. She said the neighbours know. I said, ‘Tell them she has gone to Penang for further education, don’t tell them that your daughter is here’.”14 |

| Louis Kandiah was a male nurse in Tan Tock Seng Hospital before he was transferred to Trafalgar Home in the 1950s. He worked there until he retired. |

| Leprosy is not really an infectious disease |

| “Leprosy is not really an infectious disease. I have seen couples marry each other and they have children. None of the children has leprosy. They were brought up by parents who have leprosy.”15 |

| Joyce Fung Yong Siang began working in Trafalgar Home in 1973. She was a senior social worker there from 1976 to 1981. |

If left untreated, leprosy is a debilitating and disfiguring disease that causes intense pain to sufferers as the disease progresses. It affects the nerves, skin, eyes and respiratory tract. The nerve damage can result in the crippling of hands and feet, with fingers and toes sometimes requiring amputation. Photo from iStock. If left untreated, leprosy is a debilitating and disfiguring disease that causes intense pain to sufferers as the disease progresses. It affects the nerves, skin, eyes and respiratory tract. The nerve damage can result in the crippling of hands and feet, with fingers and toes sometimes requiring amputation. Photo from iStock. |

Lorong Buangkok School

Of the 1,358 cases of leprosy registered in Singapore between 1962 and 1967, 150 were under 15 years of age.16 The children admitted to Trafalgar Home lived in dormitories and studied at Lorong Buangkok School, which had been set up in 1947 to cater to children with leprosy.17

At the school, which was renamed Lorong Buangkok Government English School in 1958, lessons were taught by the Catholic FMDM nuns, trained teachers as well as educated residents who became teaching aides. Many of the teachers were themselves patients of the home, educators who had qualified as teachers prior to contracting the disease.

School was a major part of life for most of the children in Trafalgar Home. They would wake up at seven in the morning, put on the school’s blue and white uniform, and walk the half-kilometre from their dormitories to the school. The school catered to children from Primary One until Secondary Four.

Minister for Health A.J. Braga (third from left) visiting Lorong Buangkok School for children with leprosy in 1955. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Minister for Health A.J. Braga (third from left) visiting Lorong Buangkok School for children with leprosy in 1955. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The children of Trafalgar Home came from varied backgrounds: some were from poor families with little prior education while others had previously attended established schools with high academic standards. The nuns and teachers did what they could to provide education for this diverse group of children. Some students even managed to take their Senior Cambridge Certificate examination at the school.

| LEPROSY AND ITS CURE |

| Leprosy is a long-term infection caused by the bacillus, Mycobacterium leprae. It was first discovered by the Norwegian physician Gerhard Armauer Hansen in 1873, which is why leprosy is also known as “Hansen’s disease”. It is the first bacterium to be identified as causing disease in humans.18 |

| Primarily affecting the skin, nerves, eyes and respiratory tract, the progression of the disease can lead to a loss of sensation, skin ulcers, nerve damage, muscle weakness and atrophy as well as permanent disabilities. Chronic ulcers sometimes resulted in the necessary amputation of limbs, which is why leprosy is often viewed as a mutilating disease that causes fingers and toes to “drop off”. Facial palsy, blindness, claw-hands and foot-drop are common permanent disabilities associated with the disease. |

| Mycobacterium leprae is slow-growing with an incubation period of about five years. Although transmitted via contact with fluids from the nose and mouth of people with the disease, leprosy is not highly infectious, contrary to popular belief.19 The onset of the disease can be insidious however, and the first signs often appear on the skin as lesions or raised, red patches. As the disease advances, the damage to the nerves and muscles can result in much pain. |

| Sulfa Drugs as a Cure |

| From the 1920s to the 1930s, in a laboratory in Germany, a doctor and a chemist tested one chemical after another in a bid to find a cure for bacterial infections. The physician, Gerhard Domagk, had fought in World War I and had witnessed the suffering and deaths of thousands of soldiers due to bacterial infections such as cholera, typhoid fever, gas gangrene and tuberculosis. After the war, he dedicated his life to finding a way to eradicate bacteria that invaded the human body. |

| Domagk and the chemist Josef Klarer tested many chemicals from the late 1920s. Following years of failures and endless research, they finally discovered a compound – a red dye with a sulphur atom attached to it – that produced results. After being injected with this compound, bacteria-infected mice became free from infection. The compound was later patented as Prontosil and became the world’s first commercially available antibiotic.20 It was the first in the class of drugs called sulphonamides, also known as sulfa drugs, that were effective antibiotics. This drug marked a new era in medicine and in the treatment of bacterial infections.21 |

| Dapsone is a sulfa drug that was subsequently found to be effective against leprosy. However, the use of dapsone gave rise to a drug-resistant variant of the bacteria, which is why a multi-drug therapy consisting of dapsone and two other antibiotics, rifampicin and clofazimine, eventually became the standard treatment for leprosy. In Singapore, treatment by dapsone began in the 1950s. |

|

| German physician Gerhard Domagk and chemist Josef Klarer discovered a compound – a red dye with a sulphur atom attached to it – which was later patented as Prontosil and became the world’s first commercially available antibiotic. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. |

Life After Leprosy

In the 1930s, researchers discovered sulfa drugs – a class of antibiotics – that led to the development of dapsone, which kills the bacteria that causes leprosy. Doctors eventually developed a multi-drug therapy consisting of dapsone and two other drugs, rifampicin and clofazimine, that became the standard treatment for leprosy. At last, there was a cure for the disease. In Singapore, treatment by dapsone began in the 1950s.

The Leprosy Act, which mandated the segregation of infectious cases of leprosy, was repealed in 1976 and replaced by the Infectious Diseases Act. With the repeal, the remaining institutions with compulsory segregation were progressively shut down. Trafalgar Home was eventually closed in 1993.22 Today, leprosy is managed by the National Skin Centre, while other infectious diseases come under the purview of the National Centre for Infectious Diseases.

With the closure of Trafalgar Home, some residents decided to move to the Singapore Leprosy Relief Association Home in Buangkok. Although cured, they had lived in Trafalgar Home for so many years that they no longer had a home to return to. Some were left with deformed limbs and did not want to go back to a society that might not accept them as they were.

The rest, upon recovery, attempted to return to a normal life. But the process of social reintegration was far from easy. Some had lost contact with their loved ones while others were turned away by their families. Some women also discovered that their husbands had left them and remarried. Because of the stigma, many lied when neighbours and friends asked about their long absence. Former patients thus felt a deep ambivalence when they were discharged: although now free to integrate back into society, they did not know if they would be welcomed.

While there were difficulties, many of those who were cured managed to rejoin mainstream society. They went on to carve out successful careers as teachers, nurses, clerks and in the army. Many also contributed economically and socially to a newly independent Singapore in its formative years.

Today, the National Skin Centre in Singapore treats about 10 to 15 new leprosy patients each year. Although a handful are Singaporeans, the majority are migrant workers from countries like Indonesia, the Philippines, India, Bangladesh and Myanmar.23

The illness remains a problem in some countries. In India, for example, alarm bells rang when the Central Leprosy Division of the health ministry reported 135,485 new leprosy cases in 2017.24 One of the reasons for the resurgence of the disease could be the reluctance to seek treatment due to fear.

With multi-drug therapy providing an effective cure, leprosy is no longer the dreaded disease it once was. Yet while treatment is available, the deep-seated fear and social stigma remain as strong as ever.

|

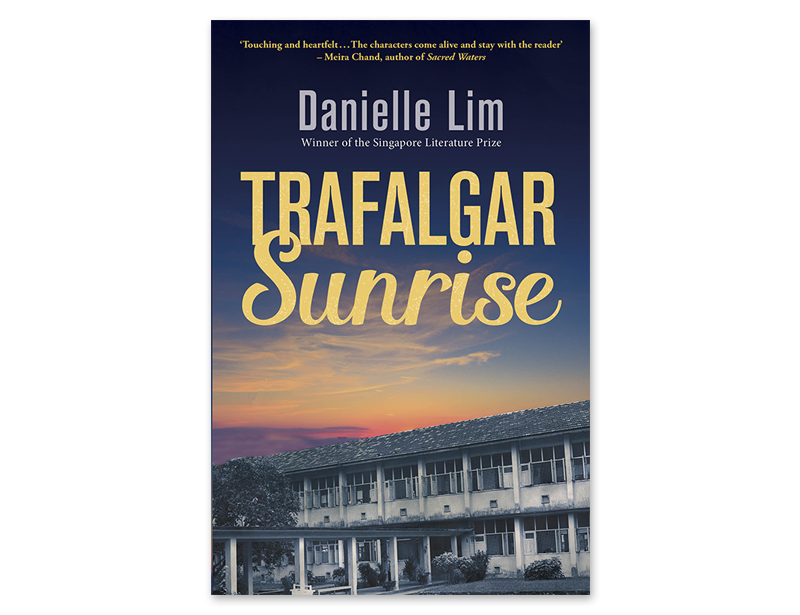

| In Trafalgar Sunrise (2018), ward sister Grace Hwang battles alongside fellow healthcare workers in Singapore during the SARS outbreak in 2003. In the thick of it, she looks back at her teenage years in Trafalgar Home, a leper asylum where Alice, her best friend, was forced to give her newborn up for adoption. With Alice now in the last stages of cancer, Grace attempts to reunite the mother with her long-lost daughter before time runs out. Trafalgar Sunrise is Danielle Lim’s first work of fiction. Her book is based on accounts by former residents of Trafalgar Home and nurses who fought the SARS outbreak. The book is available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries (Call nos.: RSING S823 LIM and SING LIM) as well as for digital loan on nlb.overdrive.com. It also retails at major bookshops in Singapore. |

Danielle Lim is an award-winning Singaporean author whose memoir about mental illness, The Sound of SCH, won the Singapore Literature Prize for non-fiction in 2016. Her latest book, Trafalgar Sunrise, was a

finalist at the 2019 Singapore Book Awards. She is a lecturer at Nanyang and Republic polytechnics.

Danielle Lim is an award-winning Singaporean author whose memoir about mental illness, The Sound of SCH, won the Singapore Literature Prize for non-fiction in 2016. Her latest book, Trafalgar Sunrise, was a

finalist at the 2019 Singapore Book Awards. She is a lecturer at Nanyang and Republic polytechnics.

NOTES

-

Khong, K.Y. (1969, September). Leprosy in Singapore: A survey of this disease between the years 1962–1967. Singapore Medical Journal, 10 (3), 194–197, p. 194. Retrieved from Singapore Medical Journal website. ↩

-

Noordeen, S.K., Bravo, L.L, & Sundaresan, T.K. (1992). Estimated number of leprosy cases in the world. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 70 (1), 7–10. Retrieved from World Health Organization website. ↩

-

World Health Organization (2011). Weekly epidemiological record no. 36, 86, 389–400. Retrieved from World Health Organization website. ↩

-

Seow, C.S. (1995). Leprosy – An update for clinicians [Bulletin for Medical Practitioners, National Skin Centre]. Retrieved from National Skin Centre website. ↩

-

Loh, K.S. (2009). Making and unmaking the asylum: Leprosy and modernity in Singapore and Malaysia (p. 21). Petaling Jaya: Strategic Information and Research Development Centre. (Call no.: RSING 614.54609595 LOH) ↩

-

Loh, 2009, p. 66. [Note: Before dapsone was used to treat leprosy, the main form of treatment was an injection of chaulmugra oil extracted from the seeds of the Hydnocarpus wightiana, a tropical tree indigenous to India and Southeast Asia.] ↩

-

Lim, K.C. (Interviewer). (1987, September 30). Oral history interview with Louis Kandiah [Recording accession no. 000822, reel 3 of 8]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Lee, P. (Interviewer). (2000, July 12). Oral history interview with Joyce Fung Yong Siang. [Recording accession no. 002354, 6 reels]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. [Note: Reels 1–3 are embargoed] ↩

-

Khong, Sep 1969, p. 194. ↩

-

World Health Organization. (2019, September 10). Leprosy: Keyfacts. Retrieved from World Health Organization website. ↩

-

World Health Organization, 20 Sep 2019. ↩

-

While Alexander Fleming had discovered penicillin in 1928, before Gerhard Domagk’s discovery of Prontosil, the latter antibiotic was produced commercially before penicillin. It was only in the early 1940s that penicillin could be manufactured in industrial quantities. For the treatment of leprosy, the sulfa drug dapsone was found to be effective. ↩

-

Hager, T. (2006). The demon under the microscope: From battlefield hospitals to Nazi labs, one doctor’s heroic search for the world’s first miracle drug (pp. 1–5). New York: Three Rivers Press. (Electronic book) ↩

-

Infection carriers can be arrested. (1976, September 9). New Nation, p. 2; Chan, C. (2005, February 5). Where leprosy patients were isolated. The Straits Times, p. 16; Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Loh, 2009, pp. 25–26. ↩

-

Shaffiq, A (2015, February 21). Former leprosy patients at Silra Home look forward to visitors during Chinese New Year. The New Paper. Retrieved from The New Paper website. ↩

-

Menon, R. (2019, January 4). Leprosy Is making a comeback In India, but the govt wants to deny it. The Wire. Retrieved from The Wire website. ↩