Mad Dogs and Englishmen: Rabies in 19th-century Singapore

Fears of the deadly disease here led to more than 22,000 dogs being killed during the 1890s. Timothy P. Barnard sniffs out the details of this long-forgotten episode.

An 1879 watercolour painting by John Edmund Taylor of a European woman with her pet dogs at the Singapore Botanic Gardens. Throughout the 1890s, no dogs were allowed into Singapore due to an outbreak of rabies among the pet dog population. Image reproduced from Sketches in the Malay Archipelago: Album of Watercolours and Photographs Made and Collected by J.E. Taylor. Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

An 1879 watercolour painting by John Edmund Taylor of a European woman with her pet dogs at the Singapore Botanic Gardens. Throughout the 1890s, no dogs were allowed into Singapore due to an outbreak of rabies among the pet dog population. Image reproduced from Sketches in the Malay Archipelago: Album of Watercolours and Photographs Made and Collected by J.E. Taylor. Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

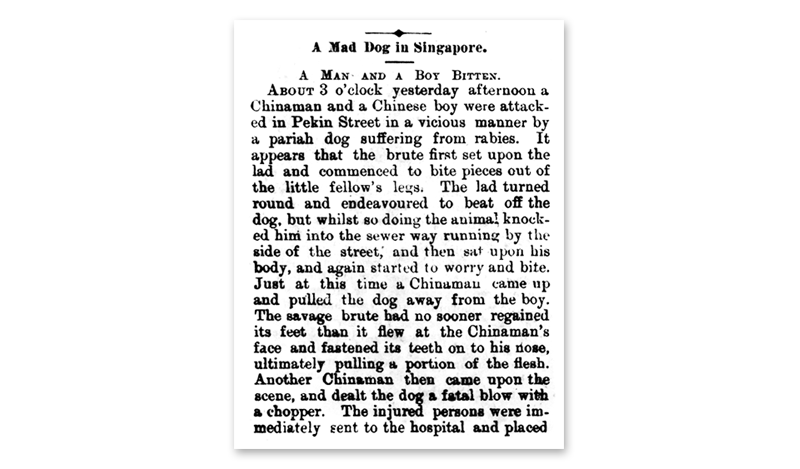

The blacksmith’s son was one of the first victims. It was about three in the afternoon and the boy was playing outside his father’s shop in Pekin Street when a rabid dog suddenly appeared. The dog went after the boy, biting “pieces out of the little fellow’s legs.” While fighting off the animal, the boy fell into a sewer drain, taking the dog with him. When the boy’s father rushed to help, the dog “flew at the Chinaman’s face and fastened its teeth on his nose, ultimately pulling a portion of the flesh”. The pair were ultimately saved by a passerby who killed the dog with a chopper.1

Although the boy survived the initial attack, which took place in early September 1889, he fell seriously ill about a month later, and his last hours were “simply agonizing to witness”, according to The Straits Times. “He was attacked with periodical convulsions, when he would call for water, but on water being brought to him, he would draw back and bark after the fashion of a dog, and so his agony continued until death put an end to his sufferings.”2

This horrific incident marked the beginnings of the “Hydrophobia Scare of 1889” as it came to be known in Singapore,3 which saw calls for all dogs to be quarantined on St John’s Island for six months or be killed. And although blame was initially laid at the paws of the numerous strays wandering around Singapore, the source of the rabies outbreak was actually a shipment of pure-bred dogs that had arrived from England five years earlier. It was only in 1899, 10 years after the outbreak, that rabies was completely eradicated from Singapore. This was only achieved, though, by putting down more than 22,000 dogs over the course of a decade.

The Straits Times reporting the attack on the blacksmith and his son by a rabid dog on Pekin Street. The Straits Times Weekly Issue, 9 September 1889, p. 2.

The Straits Times reporting the attack on the blacksmith and his son by a rabid dog on Pekin Street. The Straits Times Weekly Issue, 9 September 1889, p. 2.

Dogs in Early Singapore

Although archaeologists have yet to find any fossilised canine remains in Singapore’s acidic soil, it is likely that dogs roamed the ancient settlement of Temasek as far back as the 13th century. Dogs were certainly present in early colonial societies throughout Southeast Asia. As John Crawfurd, the second Resident of Singapore, wrote, “the dog is found in all the islands of the Archipelago in the half-domestic state in which it is seen in every country of the East”. He added, “it is the same prick-eared cur as in other Asiatic countries, varying a good deal in colour – not much in shape and size – never owned – never become wild, but always the common scavenger in every town and village”.4

Most dogs in early colonial Singapore roamed in packs about the town, making them “one of the greatest nuisances in the settlement”. The “wretched creatures” would follow the “dust carts” that collected rubbish, or tag along with soldiers who were carrying out their duties. A letter published in The Singapore Free Press in January 1843 complained that “every morning when the guard is relieved at the Court house a swarm of Pariah dogs come out with the soldiers, and attack the passing natives and many times throw them down and bite them, and tear their cloths off, and the sepoys appear to injoy [sic] it, although he says they take the dogs off when they see them going to extremities…”.5 In August 1844, an irate member of the public wrote that “when the sepoys exchange guard at the Court House they are invariably followed by about 30 dogs and these are a complete nuisance to the neighbourhood”.6

The annoyance created by these stray dogs was so great that as early as April 1833, the authorities had issued a notice that read: “All dogs found running loose about the streets between the 8th and 18th… will be destroyed.”7 This was the beginning of an approach used throughout the world to control canines: with extreme malice, stray dogs were to be culled.

The culling exercises typically occurred four times a year over three or four days, although extra sessions could be arranged if needed. Despite regular culling, however, mongrels were still found on the streets of Singapore well into the 1880s. The small consolation was that while the stray dogs were a significant public nuisance, cases of rabies were few and far between. But all this was to change with the arrival of the steamship Oxfordshire in April 1884.

Tainted Pure Breds

When the Oxfordshire pulled into the harbour of Singapore, it carried on board “some twenty or thirty well bred dogs”, including terriers, bulldogs, greyhounds and poodles. These animals were ferried ashore, along with English potatoes, and auctioned off on 7 April at Commercial Square (present-day Raffles Place).8

In contrast to the semi-feral native mongrels, these imported dogs were the result of breeding and eugenics, the fruits of a movement that had begun a few decades earlier in England: the creation of a canine sub-species with desired characteristics and were deemed to be “pure”. These greyhounds and terriers were symbols of social divisions and distinctions. To own one of these living examples of imperial superiority characterised its human master as a member of the elite of a rapidly changing and industrialising society.

The residents of Singapore who successfully secured a four-legged friend that fateful day in April, however, had no inkling of what was to come. During the journey to Singapore, one or two of the dogs that showed symptoms of rabies had to be culled. Over the next few years, these “fancy dogs” sparked an outbreak of rabies that led to increased restrictions and regulations as well as further domestication of the common pet in Singapore. Ultimately, these imported animals would lead to changes in the way Singapore regulated and domesticated dogs.9

About a month after the Oxfordshire docked, rabies began appearing among the local canine population. It was reported that there had been “a few peculiar cases of mania” among the dogs in the military encampment near the Botanic Gardens. But this was only the beginning: in quick succession, three Europeans died of hydrophobia.10

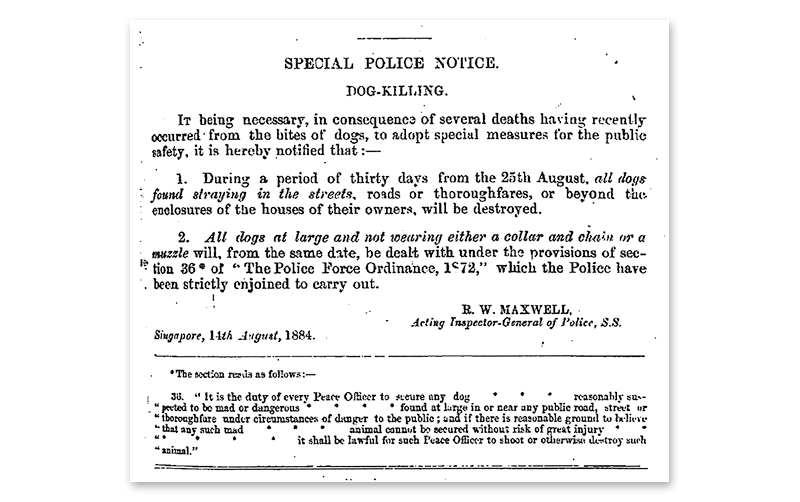

The initial response to the rabies outbreak was to simply cull mongrels, a practice that had existed for decades in Singapore. Although efforts were ramped up in July 1884 to limit the stray dog population, rabies persisted. In mid-August, the authorities announced that they would begin a month of dog-killing on 25 August. “All dogs at large and not wearing either a collar and chain or a muzzle” would be killed.11 The culling was subsequently extended, continuing well into 1885.

A police notice dated 14 August 1884 listing the measures adopted by the police in light of several deaths arising from dog bites. With effect from 25 August, all stray dogs would be killed and dogs not wearing either a collar and chain or a muzzle would be dealt with. Special Police Notice: Dog-killing. (1884, August 14). Government Gazette. CO276/15: Government Notification, No. 345, p. 871.

A police notice dated 14 August 1884 listing the measures adopted by the police in light of several deaths arising from dog bites. With effect from 25 August, all stray dogs would be killed and dogs not wearing either a collar and chain or a muzzle would be dealt with. Special Police Notice: Dog-killing. (1884, August 14). Government Gazette. CO276/15: Government Notification, No. 345, p. 871.

When cases of rabies persisted, particularly in residential areas where people kept dogs as pets, the authorities began to realise that the disease was endemic among the well-bred pets. To deal with the problem, starting from mid-1885, the direct importation of dogs into Singapore was prohibited and all pet dogs had to be confined within houses or at least chained up in compounds, while orders were issued “to kill all dogs, day and night”.12

Barking Up the Wrong Tree

Rabies persisted in Singapore for the remainder of the 1880s despite quarantine provisions and increased efforts at exterminating stray mongrels. The disease had, unfortunately, become endemic among the pet dog population on the island, and these precious animals were under the protection of wealthy residents who were reluctant to address the root of the problem. A reminder of this conundrum occurred in December 1886 when a Chinese man went to the Central Police Station and requested to be sent to the hospital. He died shortly thereafter from hydrophobia. Several weeks earlier, “a small dog belonging to one of the European police” had bitten the man.13

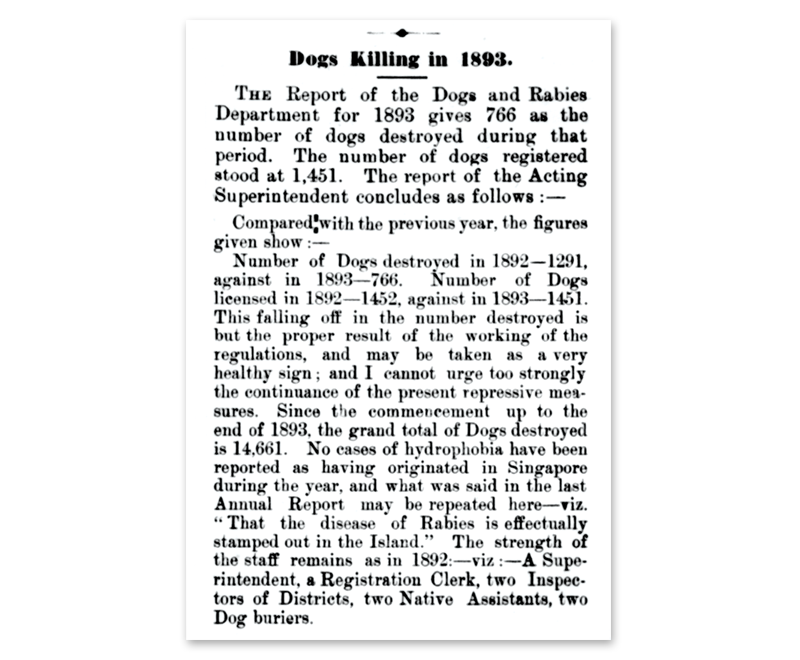

The Dogs and Rabies Department reported that 766 dogs were culled in 1893, compared with 1,291 the year before. The reduction in the number of dogs killed was attributed to the new regulations that had been introduced. No cases of hydrophobia were reported for the year 1893. The Straits Times, 5 April 1894, p. 3.

The Dogs and Rabies Department reported that 766 dogs were culled in 1893, compared with 1,291 the year before. The reduction in the number of dogs killed was attributed to the new regulations that had been introduced. No cases of hydrophobia were reported for the year 1893. The Straits Times, 5 April 1894, p. 3.

Even though public dog culling had become the norm, rabies remained entrenched among the pets of the elite. Thus the government imposed a dog tax, with its associated licensing and registration.14 The main goal of the tax, which came into effect in December 1888, was to force residents to declare their responsibilities. Under the new directives, every dog in Singapore had to be “registered by the Commissioners of the Municipality within which the dog is kept”.

For an annual fee of $1 within the Municipality and 50 cents in rural areas, residents received a “metal label bearing the registered number of the dog in respect of which the tax is paid”. The government also maintained a record containing the name of the owner, along with other information that identified the animal. Any dog found without a collar and identification number would be “destroyed, impounded or dealt with”. In the first month of implementation, 201 dogs were registered; by the end of 1889, the figure had reached 3,664.15

A stray dog sniffing the goods of a hawker. From as early as the 1830s, stray dogs had roamed the town of Singapore in packs, creating a nuisance for some. The authorities carried out dog-culling exercises to control the canine population. Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

A stray dog sniffing the goods of a hawker. From as early as the 1830s, stray dogs had roamed the town of Singapore in packs, creating a nuisance for some. The authorities carried out dog-culling exercises to control the canine population. Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Unfortunately, the attack on the blacksmith and his son in September 1889 exposed the limitations of this approach. The rabid canine in question had been registered – No. 183 – and the owner was a Tah Wah Liang who lived at 148 Kampong Bugis.16 After the boy died, several other people also contracted the disease in similar attacks. This was the beginning of the greatest rabies outbreak in Singapore’s history: the Hydrophobia Scare of 1889. Because preventive measures had not adequately addressed the core issue – the presence of the disease among dogs owned by the rich – panic began to seep into society.

| WHAT IS RABIES? |

| Rabies is caused by a virus. Unlike most viruses which travel through the bloodstream, Rabies lyssavirus moves through the nerves and does so slowly. It enters the body through a bite, or breaks in the skin. Once it enters a nerve, the virus usually proceeds at a pace of only a few centimetres a day until it reaches the brain. It then begins replicating itself in the brain, causing inflammation of the organ and destroying nerve cells in the process, leading to a warping of normal behavior while stimulating aggression. If any other mammal is bitten during these periods of aggression, the disease could spread.17 |

| Rabies has been present for millennia, having been reported in ancient Mesopotamia and India. In an age when the source of most diseases was thought to result from “bad air”, it was one of the few whose real origins were understood: it came from the bite of an animal.18 |

| Although it is most closely associated with dogs, almost all mammals can catch rabies, which refers to the disease in animals; in the 19th century, humans were said to have caught “hydrophobia”. Meaning the fear of water, hydrophobia refers to a particular symptom where the victims recoil violently when offered water, although they may be thirsty.19 |

| The disease begins to manifest itself after one to three months with a fever and nerve tingling at the site of the bite. Violent spasms, uncontrolled excitement, paralysis of random limbs, confusion and a loss of consciousness follow. The carrier of the virus will then violently attack others, often followed by periods of lucidity. |

| Rabies created a tremendous amount of anxiety and fear throughout the world in the 19th century, and the conquest of the disease was a scientific triumph in an era when there were great advances in the knowledge of diseases and germ theory. |

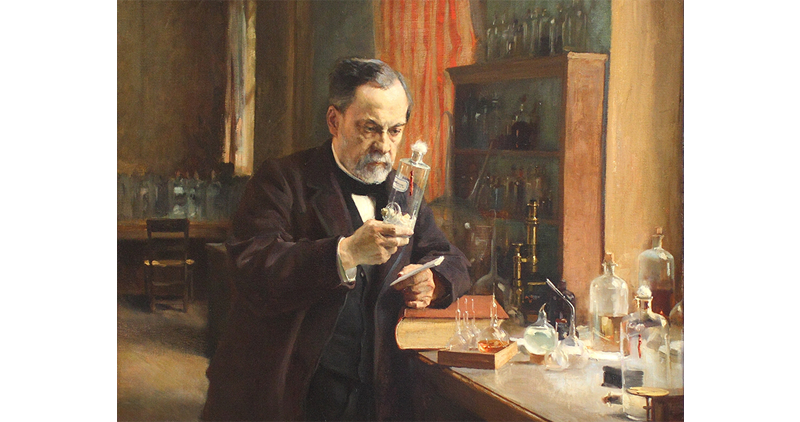

| Much of the credit was due to the pioneering French microbiologist Louis Pasteur, who began experiments to develop a vaccine in 1880. |

| Four years later, Pasteur announced that he had found a treatment involving a modified rabies virus of reduced virulence. He then turned his attention to the development of a treatment for hydrophobia and, in 1885, used graduated doses of the vaccine to save the life of a young boy named Joseph Meister. The development of the rabies vaccine was a global sensation.20 |

| It was around this time that the disease entered Singapore.21 In the late 1880s, the Legislative Council considered making the rabies vaccine in Singapore, but the high cost and the difficulties involved in operating vaccine-making facilities were a deterrence.22 |

|

| An oil painting of the French microbiologist Louis Pasteur working in his laboratory by Finnish painter and illustrator Albert Edelfelt, 1885. Pasteur developed the first vaccine for rabies, which was successfully used on a nine-year-old boy in 1885. This painting is found in the collection of the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. Image reproduced from Wikimedia Commons. |

Drastic Measures

Soon after the death of the blacksmith and his son, the Legislative Council met in October 1889 to discuss whether increased regulation was the best way to resolve the situation. The main proposal under consideration called for a reminder that all dogs be registered as well as “compulsory muzzling under a penalty of non-compliance”. At the same time, the Municipal Commissioners formed a Hydrophobia Committee, which released a report in January 1890.23

The committee supported a combination of “extirpation and quarantine”, but were reluctant to enforce both measures. As a compromise, they advocated a combination of drastic measures, including the continued culling of stray dogs and muzzling as well as registration, higher taxation, strict control and a restriction on the number of dogs allowed in each residence.24

The ideal quantity was two dogs per household. “This number is in most cases sufficient for protection purposes, and if any additional dog be licensed it should be on special conditions.”25 The Municipal Commission arranged for the registration of all dogs on the island to take place at police stations and at the main Municipal Office, while active groups of civil servants roamed the island to exterminate stray dogs.

In March 1891, the Legislative Council met to finalise the new regulations and ultimately passed the Singapore Dog Ordinance of 1891. Under the legislation, every canine in Singapore had to be registered and muzzled at all times when outdoors. Owners were required to bring their dogs to the Municipal Office to obtain the licence. If they were unable to do so, they had to provide a full description of the dog “written in English” to be “handed to the registering officer”. The officer would “properly affix” the badge “bearing the registered number for the current year” to the dog’s collar. Each owner would then receive a printed receipt and licence “in which shall be entered a description of the dog”. Any individual harbouring an unregistered dog was subject to a fine of $10.26

The solution after several years of rabies outbreaks was thus to register, muzzle, destroy and ban. The decision to muzzle dogs was seen as a compromise, as the cost of quarantining dogs would have been borne by the owners, which would put it beyond the reach of many. “On the other hand, muzzling does not cost much, and every man, be he rich or poor, if he so desires, can save his dog.”27 In addition, the government would provide the first muzzle free-of-charge.

Before the muzzles could arrive, however, a new wave of government-approved dog cullings had commenced under the leadership of three more dog inspectors hired to carry out the task. It was a period in which “the Dog exterminators seem to breathe vengeance against the canine tribe. No mercy is shown to poor doggie, and not the ghost of a chance is ever given him to escape the deadly missile”.28

At times, the dog-culling campaign went too far. There was a public outcry over the killing of a dog belonging to a person named Sahat on 24 August 1891. The dog inspector, A. Cheeseman, killed the dog in the verandah of Sahat’s home on Serangoon Road, despite protests from the lady of the house. The Straits Times reported the incident:

“A dog having been shot, while it was attached by a very short chain to the verandah pillar of a compound house; and while a woman and children were weeping within a few feet of it; and while the woman was praying for the favorite’s life, and offering to muzzle the dog, with the muzzle that they had removed to feed it.”29

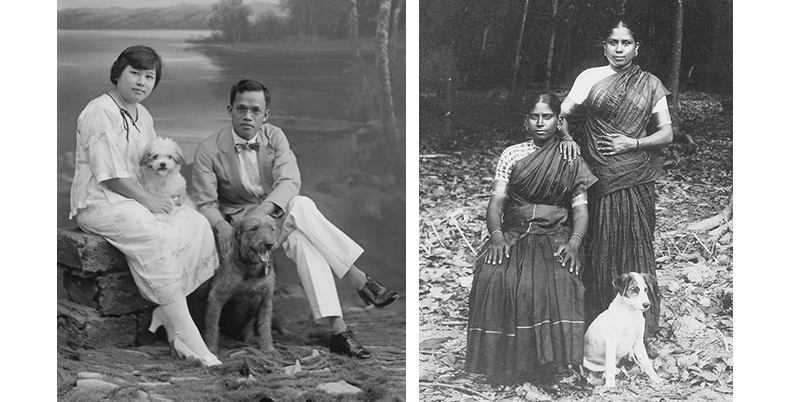

Keeping dogs was popular with the local population of Singapore as well, as these two photos from the early 20th century show. Lee Brothers Studio Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore (left) and courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board (right).

Keeping dogs was popular with the local population of Singapore as well, as these two photos from the early 20th century show. Lee Brothers Studio Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore (left) and courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board (right).

By March 1892, according to The Daily Advertiser, “it is positively a wonder that there are any more dogs left to kill” in Singapore, which led government officials to begin considering whether the regulations on muzzling, registration and importation of canines were still necessary.30 After meeting with the Executive Council, the decision was made to extend the dog regulations for another year, although the issuance of free muzzles was discontinued in April 1892. There was also a reduction in the number of personnel in the Rabies Suppression Unit. Enforcement in the Municipality shifted to regulation and monitoring, with dog inspectors issuing 94 summonses in 1892, 77 of which were orders to pay fines.31

Rabies Eventually Eliminated

By early 1893, it appeared that rabies in Singapore had been contained. In January, the government published an assessment of the measures it had taken and trumpeted their effectiveness. There were no reported cases of hydrophobia for the entire year of 1892; the last case had been the death of a Chua Kim Soon in October 1891.

The absence of rabies cases for the next two years resulted in the promulgation of the Singapore Dogs Orders 1893. The new regulations revoked the need for a muzzle within the Municipality, although all dogs still had to be registered and wear a collar with an identifying tag. Any dog without such a collar could be culled. The ban on the importation of dogs continued.32

In 1894, funding for the Department for the Suppression of Rabies was dropped from the budget. The police assumed responsibility for licensing and other related activities, particularly those taking place outside the Municipality. By 1896, the authorities were ready to further ease some of the other restrictions as there had not been a reported case of rabies in Singapore since 1891. G. Owen, the Superintendent of Rabies Suppression, announced that there was “no danger of the disease again showing itself”, and proclaimed that throughout the island, “with the exception of an occasional unhealthy looking dog, the present classes of native dogs on the Island are strong and healthy looking and cared for”.33

The suppression of rabies was a triumph for the Municipal Commission as well as the Straits Settlements government. Government programmes had rid the island of a scourge and brought under control the canine nuisance that had plagued the residents for decades.

During the 1890s, over 22,000 dogs were killed in Singapore according to government records, while the number of registered dogs in the Municipality was fewer than 3,000. The only drawback, according to the government report, was that pedigree dogs – such as fox terriers, spaniels and setters – had “greatly degenerated from lack of new stock and hardly a pure bred dog is now to be met with”. By 1899, the Chief Medical Officer was able to announce that “rabies has been completely stamped out of the Island of Singapore”. This occurred three years before the disease was eradicated in Britain.34

To start the new century, Superintendent Owen asked to return to England on home leave. The government approved the sabbatical and used his absence to ease many of the strict regulations relating to dogs. Beginning in August 1900, dog owners could attach the registration badge to their pet’s collar without the presence of a government official. More importantly, canines were now allowed ashore from ships as long as they went directly to the quarantine station for animals that had been established on St John’s Island. The dog owner would pay the fees for the period of upkeep and inspection.35

This established the quarantine and importation rules for dogs, which remained for the rest of the colonial period in Singapore. Dogs were allowed once again, but only if they were monitored, registered and controlled – as well as tolerated – by colonial society.

|

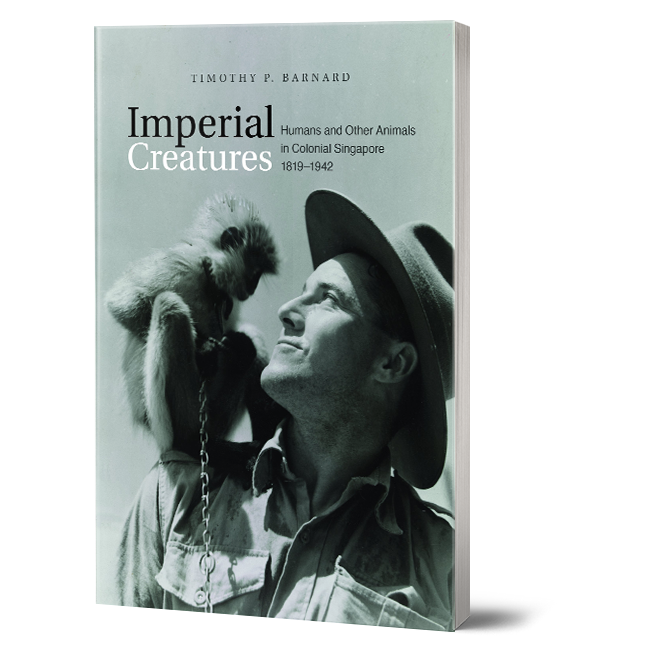

| This essay is based on a chapter in Timothy P. Barnard’s Imperial Creatures: Humans and other Animals in Colonial Singapore, 1849–1942 (2019), which retails at major bookshops. It is also available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries (Call nos.: RSING 304.2095957 BAR and SING 304.2095957 BAR). |

Dr Timothy P. Barnard is an associate professor in the Department of History at the National University of Singapore, where he specialises in the environmental and cultural history of Southeast Asia.

Dr Timothy P. Barnard is an associate professor in the Department of History at the National University of Singapore, where he specialises in the environmental and cultural history of Southeast Asia.

NOTES

[All other Colonial Office (CO) reports and Minutes of the Proceeding of the Municipal Commissioners (MPMC) can be accessed at NUS Libraries.]

-

A mad dog in Singapore. (1889, September 9). The Straits Times Weekly Issue, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Hydrophobia in Singapore. (1889, October 7). The Straits Times Weekly Issue, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Technically, rabies is the disease in animals while hydrophobia – the fear of water – historically refers to the disease in humans caused by rabies. The term “hydrophobia” is derived from one of the symptoms in humans affected by the virus. During the 20th century, it became more common to call the disease in both animals and humans “rabies”. ↩

-

Crawfurd, J. (1856). A descriptive dictionary of the Indian Islands and adjacent countries (p. 121). London: Bradbury and Evans. Retrieved from BookSG; Mikhail, A. (2015, May). A dog-eat-dog empire: Violence and affection on the streets of Ottoman Cairo. Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, 35 (1): 76–95, p. 87. Retrieved from ResearchGate. ↩

-

Untitled. (1843, January 5). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Correspondence. (1844, August 8). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Notice. (1833. April 4). Singapore Chronicle and Commercial Register, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Singapore Debating Society: Hydrophobia in Singapore. (1889, October 15). The Straits Times Weekly Issue, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Notebook volume 3 (p. 123) (1891–1896). HNR/3/2/3. Papers of Henry Nicholas Ridley, Director of Gardens and Forests, Straits Settlements. Retrieved from Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Library and Archives. ↩

-

CO275/39: Report of Committee Appointed to Enquire into the Question of Rabies in Singapore, Papers Laid before the Legislative Council, No. 4 (1890), p. C19. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore; Page 2 Advertisements Column 4: Sale of English dogs. (1884, April 4). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

CO275/39: Report of Committee Appointed to Enquire into the Question of Rabies in Singapore, p. C19. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore; Untitled. (1885, February 10). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, Henry Nicholas Ridley Collection, HNR/3/2/3: Notebooks, Vol. 3, p. 123. ↩

-

Hydrophobia. (1884, July 30). The Straits Times Weekly Issue, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

CO273/246/4381: Report on the Suppression of Rabies, (1899), p. 224; Prevention of disease. (1886, November 13). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; CO276/17: Ordinance No. XIX of 1886, (1886), pp. 2139–42; CO276/16: Government Notification, No. 341, 1885, pp. 1048–9. ↩

-

Occasional reports of a similar nature appeared periodically in the newspapers. See Notes. (1886, December 4). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 331. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; CO276/18: Government Notification, No. 69, 1887, p. 186. ↩

-

CO276/18: Government Notification, No. 69, 1887, p. 186; The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 4 Dec 1886, p. 331. ↩

-

CO276/19: Government Notification, No. 582 (1888), p. 2023; CO276/19: Government Notification, No. 583 (1888), p. 2024; CO276/19: Government Notification, No. 280 (1888), pp. 953–4; CO273/246/4381: Report on the Suppression of Rabies (1899), p. 225; CO276/19: Government Notification, No. 752 (1888), p. 2539; NA425: MPMC: 6 Jan 1888, p. 1411; 1 Aug 1888, p. 1491. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore. ↩

-

The Straits Times Weekly Issue, 9 Sep 1889, p. 2. ↩

-

Wasick & Murphy. (2012). Rabid: A cultural history of the world’s most diabolical virus (pp. 3–5). New York: Penguin Books. (Call no.: 614.563 WAS-[HEA]) ↩

-

Wasick & Murphy, 2012, pp. 17–31. ↩

-

Wasick & Murphy, 2012, pp. 8–10. ↩

-

CO275/39: Report on Hydrophobia, pp. C76–79; Pemberton, N., & Worboys, M. (2007). Rabies in Britain: Dogs, disease and culture, 1800–2000 (pp. 102–132). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. (Not available in NLB holdings); Wasick & Murphy, 2012, pp. 119–148. ↩

-

CO275/39: Report on Hydrophobia, pp. C76–79; Pemberton & Worboys, 2007, pp. 102–132; Wasick & Murphy, 2012, pp. 119–148. ↩

-

This is covered in a series of letters requesting the purchase of equipment and other materials found in CO273/164; CO275/39: Report on Hydrophobia, pp. C79–80. ↩

-

The prevention of hydrophobia. (1889, November 13). The Straits Times, p. 2; The prevention of hydrophobia. (1889, October 5). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Report on rabies. (1890, January 25). The Straits Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; CO275/39: Report of Committee Appointed to Enquire into the Question of Rabies in Singapore, pp. C24–5. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore. ↩

-

CO275/39: Report of Committee Appointed to Enquire into the Question of Rabies in Singapore, p. C23; NA425: MPMC: 26 Mar. 1890, p. 1682. ↩

-

CO276/22: Government Notification, No. 120, pp. 360–1; The Legislative Council. (1891, February 25). The Straits Times Weekly Issue, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; NA425: MPMC: 1 Apr. 1891, pp. 1853–4. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore. ↩

-

Government action re hydrophobia. (1891, March 10). The Daily Advertiser, p. 2; The Daily Advertiser, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

NA425: MPMC: 24 Jun 1891, p. 1884. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore; The Daily Advertiser, 10 Mar 1891, p. 2; Random notes. (1891, July 4). The Daily Advertiser, p. 2; Dog statistics. (1891, November 10). The Straits Times Weekly Issue, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The municipal dog-killing. (1891, October 7). The Straits Times Weekly Issue, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Local and general. (1892, August 8). The Daily Advertiser, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

CO276/26: Report on the Work of Suppression of Rabies; CO276/24: Government Notification, No. 159 (1892), p. 1043; Municipal Commission. (1892, March 31). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 3; The dog regulations. (1892, April 4). The Daily Advertiser, p. 3; Suppression of rabies. (1892, March 21). The Daily Advertiser, p. 3; The Municipal Commission. (1892, March 4). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 2; CO273/246/4381: Report on the Suppression of Rabies, (1899), p. 228. ↩

-

H.E.’s veto in municipal affairs. (1893, March 28). The Straits Times Weekly Issue, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; CO276/24: Government Notification, No. 163 (1893), pp. 578–9; CO273/246/4381: Report on the Suppression of Rabies, (1899), p. 228; NA 426: MPMC: 15 Feb. 1893, p. 2158; 15 Mar. 1893, pp. 2169–70. ↩

-

CO276/28: Government Notification, No. 275 (1894), pp. 734; Unlicensed dogs. (1895, January 8). The Mid-Day Herald, p. 2; Official report of the Legislative Council Meeting. (1896, April 24). The Mid-Day Herald, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Poon, S.W. (2014, March). Dogs and British colonialism: The contested ban on eating dogs in colonial Hong Kong. The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 42 (2): 308–328, p. 316. Retrieved from ResearchGate; Pemberton, N., & Worboys, M. (2007). Rabies in Britain: Dogs, disease and culture, 1800–2000 (p. 1). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. (Not available in NLB holdings); CO273/246/4381: Report on the Suppression of Rabies, (1899), pp. 230–1. ↩

-

NA427: MPMC: 20 June 1900, p. 3885; 15 Aug. pp. 3931–3. ↩