Malay Seals from Singapore

Malay seals of the 19th century hold important information says Annabel Teh Gallop.

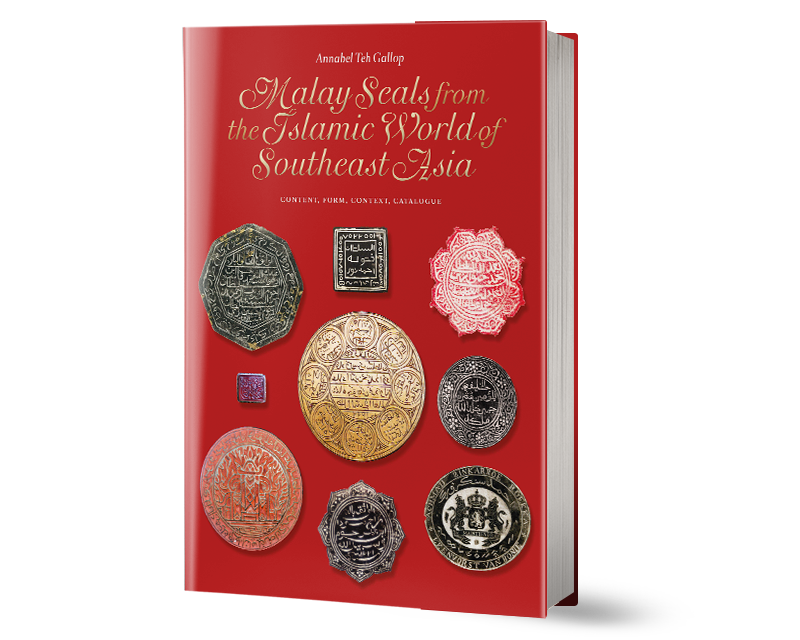

Malay seals – defined as seals from Southeast Asia, or used by Southeast Asians, with inscriptions in Arabic script – have been found everywhere in the Malay Archipelago. As small but highly visible and symbolic emblems of their owners, Malay seals were designed to portray the image of the self that the seal holder wished to project, but they were also no less strongly shaped by the prevailing cultural, religious and artistic norms of their time. These multiple layers of identity – both consciously and subconsciously revealed in seals – are recorded, explored and interpreted in a new catalogue of Malay seals.

Malay Seals from the Islamic World of Southeast Asia – published in Singapore by NUS Press in association with The British Library,1 and in Indonesia by Lontar Foundation – presents 2,168 Malay seals sourced from more than 70 public institutions and 60 private collections worldwide. The seals were retrieved mainly from impressions stamped in lampblack (a material obtained from candles or oil lamps), ink or wax on manuscript letters, treaties and other documents. In addition, around 300 silver, brass and stone seal matrices (the objects used to make the impression) are also documented.

The seals featured in the book originate from the present-day territories of Malaysia, Brunei, Singapore, Indonesia and the southern regions of Thailand, Cambodia and the Philippines, and date from the second half of the 16th century to the early 20th century. The concise and precise inscriptions on these seals, over half of which are dated, constitute a treasure trove of data that can throw light on myriad aspects of the history of the Malay world.

The catalogue is arranged geographically by clusters of kingdoms – sweeping broadly from west to east across Southeast Asia – from Aceh on the northern tip of Sumatra to Mindanao in the southern Philippines. Many of these clusters map easily onto modern political and administrative boundaries, but the chapter labelled “Johor, Riau, Lingga and Singapore”, which features 134 seals, proved harder to organise coherently than that of any other Malay state because of the uniquely complex history of the polity.

A Succession Dispute and the Arrival of Stamford Raffles

In 1811, Sultan Mahmud Syah III of the Johor-Riau empire died suddenly, without naming a successor. As his oldest son Tengku Husain (also known as Tengku Long) was in Pahang getting married at the time, a faction in the court installed the Sultan’s younger son, Tengku Abdul Rahman, as the new sultan. This act was not recognised by the most senior ministers – the Bendahara in Pahang and the Temenggung in Johor – or by Sultan Mahmud’s widow, who held the sacred regalia. She favoured Tengku Husain and by refusing to hand over the royal regalia, prevented Tengku Abdul Rahman from being ceremonially installed.

Into this scene of fractious stalemate arrived Stamford Raffles in January 1819. Seeking a new port for the East India Company, he adroitly came to an arrangement with Temenggung Abdul Rahman of Johor (who was based in Singapore). Tengku Husain was brought from Riau to Singapore and swiftly installed as a rival sultan of Johor on the morning of 6 February 1819. Thus enthroned and empowered, Husain signed a treaty that very afternoon, together with the Temenggung, granting the British permission to establish a trading post in Singapore.

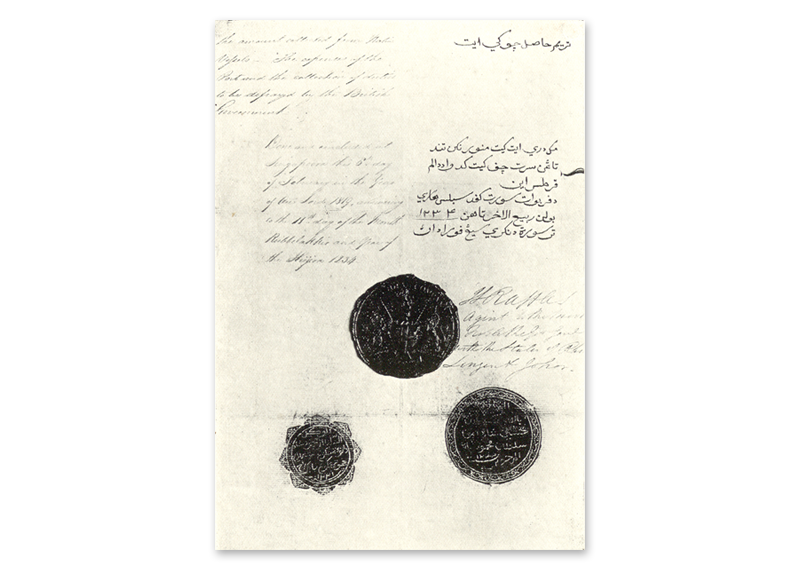

As the whereabouts of the original treaty of 6 February 1819 are unknown, all that remains today is an old photograph published in 1902 on the frontispiece of Charles Burton Buckley’s An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore which mentions that the treaty was “found among the Records in Johore”. The image shows the last page of the bilingual treaty, in English and Malay in Jawi script,2 with the red wax seal of Raffles, and the seal impressions of Sultan Husain Syah and Temenggung Abdul Rahman stamped in lampblack.3

A black and white reproduction of the last page of the treaty signed on 6 February 1819. The bilingual treaty – in English and Malay in Jawi script – shows the signature of Stamford Raffles and his red wax seal (top), and the seal impressions of Temenggung Abdul Rahman (left) and Sultan Husain Syah (right) stamped in lampblack. Image reproduced from Buckley, C.B. (1902). An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore (vol. I; Frontispiece). Singapore: Fraser & Neave, Limited. Collection of the National Library, Singapore (Accession no.: B02966444B).

A black and white reproduction of the last page of the treaty signed on 6 February 1819. The bilingual treaty – in English and Malay in Jawi script – shows the signature of Stamford Raffles and his red wax seal (top), and the seal impressions of Temenggung Abdul Rahman (left) and Sultan Husain Syah (right) stamped in lampblack. Image reproduced from Buckley, C.B. (1902). An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore (vol. I; Frontispiece). Singapore: Fraser & Neave, Limited. Collection of the National Library, Singapore (Accession no.: B02966444B).

An eyewitness account of the sealing of the treaty was given by J.G.F. Crawford, captain of the survey ship Investigator, who served under Raffles:

“Their mode of sealing is peculiar. The seal, about three inches in diameter, is made of silver, on which is deeply and admirably well engraved the name and rank of the proprieter; that is held over a candle which heats and blackens it with smoke. It then is pressed on the paper, over a soft cushion. It leaves a beautiful, clear impression of the characters, but which, I should suppose, would not last long without the greatest care being taken to prevent any friction over the soot.”4

A closer look at these two exemplars of Malay sigillography (the study of seals) illustrates the rich nuggets of historical data that Malay seals can yield upon scrutiny and study.

The Temenggung’s seal is inscribed al-wakil al-Sultan Mahmud Syah Datuk Temenggung Seri Maharaja cucu Temenggung Paduka Raja sanat 1221. This is translated into English as “The deputy of the Sultan Mahmud Syah, Datuk Temenggung Seri Maharaja, grandson of Temenggung Paduka Raja, the year 1221” (1806/7). The year on a Malay seal usually refers to the date of appointment. Hence, this is the seal granted by Sultan Mahmud Syah to the Temenggung following his installation as Datuk Temenggung Seri Maharaja in 1806, or 1221 in the Islamic calendar. It is notable that the pedigree on the seal names his grandfather rather than his father, reflecting the fact that while his father did not hold the office of Temenggung, his grandfather indubitably did.

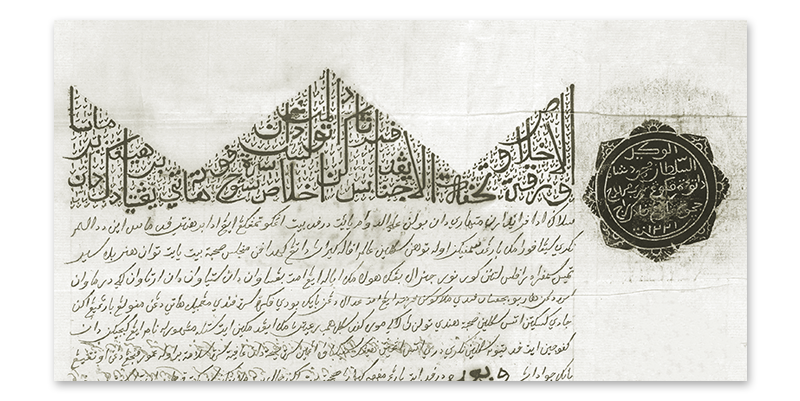

The petalled floral shape is typical of Malay seals, recalling the lotus blossom; the eight petals reflect a deep-seated Malay attachment to the cosmographical significance of multiples of four. Temenggung Abdul Rahman used this seal all his life and it is shown below impressed on a letter to Raffles in 1824. As is well known, all of Raffles’ possessions and correspondence from his second period of service in Southeast Asia were lost in the wreck of the Fame on his voyage homewards on 2 February 1824. However, this letter from the Temenggung is dated 23 August 1824 and must therefore have been sent to Raffles when he was already back in London.

Letter from Temenggung Abdul Rahman of Johor (featuring his seal) to T.S. Raffles in Bengkulu, 27 Zulhijah 1239 (23 August 1824). British Library, MSS Eur D.742/1, f. 148 (cat. 879 in Gallop 2019).

Letter from Temenggung Abdul Rahman of Johor (featuring his seal) to T.S. Raffles in Bengkulu, 27 Zulhijah 1239 (23 August 1824). British Library, MSS Eur D.742/1, f. 148 (cat. 879 in Gallop 2019).

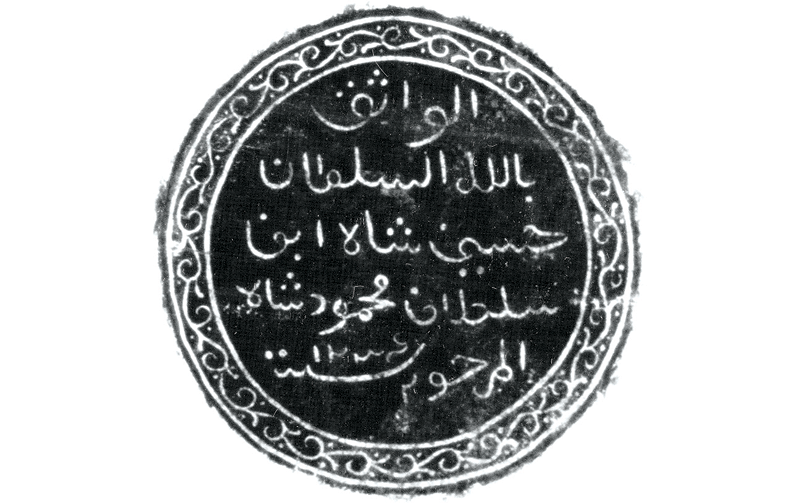

Sultan Husain’s seal, on the other hand, opens with the most common expression of piety found on Malay seals: al-wāthiq billāh al-Sultan Husain Syah ibn Sultan Mahmud Syah al-marhum sanat 1234, which means “He who trusts in God, the Sultan Husain Syah, son of the late Sultan Mahmud Syah, the year 1234” (1818/9). In order for it to be used for the treaty signing on the afternoon of 6 February 1819, the silver seal must have been made at very short notice, namely in the brief interval between Raffles’ preliminary agreement with Temenggung Abdul Rahman on 30 January, and Husain’s installation as sultan in Singapore a week later, on the morning of 6 February. It was therefore most probably made in Singapore by a silversmith in the Temenggung’s entourage.

Seals of Malay Nobles

In many parts of the Islamic world, from Istanbul to Cairo, seals were used at all levels of society, from sultans to slaves. In the Malay world however, seals were a royal prerogative and the use of seals was restricted to court circles. The clearest proof of this accepted convention was that even the famous writer Munsyi Abdullah (born Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir), who was renowned as a seal designer, did not have his own seal. His last will and testament, drawn up before he embarked on his Haj pilgrimage in 1856 – and recently exhibited in the National Library of Singapore’s exhibition “On Paper: Singapore Before 1867” – is not sealed. Thus, the story of Malay seals from Singapore is essentially a study of the seals of Sultan Husain Syah and his short-lived line, until superseded in the second half of the 19th century by the seals of the British colonial government.

Seal of Sultan Husain Syah in a letter to William Farquhar in Singapore, undated. Library of Congress, MS Jawi 12, no. 41 (cat. 983 in Gallop 2019).

Seal of Sultan Husain Syah in a letter to William Farquhar in Singapore, undated. Library of Congress, MS Jawi 12, no. 41 (cat. 983 in Gallop 2019).

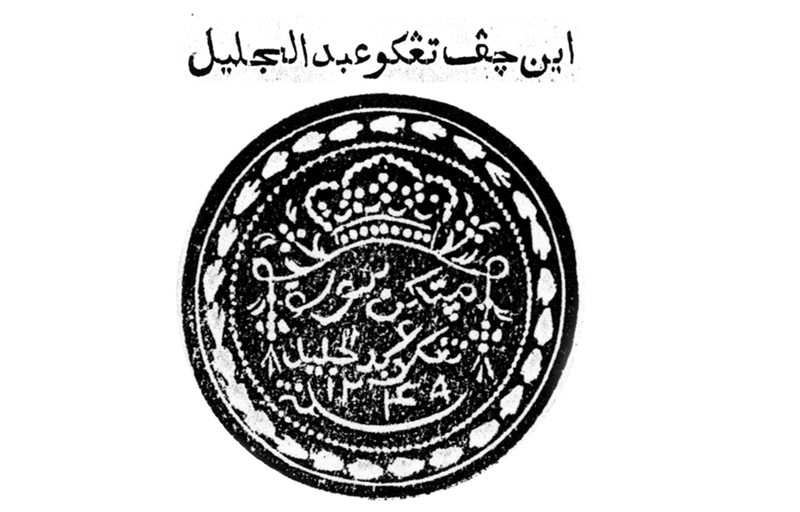

Among the seals of Sultan Husain Syah’s descendants, that of his oldest son, Tengku Abdul Jalil, is of special significance because it is the earliest dated example of lithography in Singapore. The seal appears on a letter written in Jawi from Thomas Church, the Resident Councillor of Singapore, in 1838. The letter urged the Malay chiefs to send their children for instruction at the Singapore Institution (subsequently renamed Raffles Institution in 1868).

The seal is round, with the inscription in the middle – Menyatakan surat Tengku Abdul Jalil sanat 1249, which means “Signifying a document from Tengku Abdul Jalil, the year 1249” (1833/4) – surmounted by a crown and framed by a shield-shaped looped cord; such borrowings from the iconographic vocabulary of European heraldry can be seen in some Malay seals since the 17th century.

The seal of Tengku Abdul Jalil, lithographed on a typeset printed Malay letter from Thomas Church, Resident Councillor of Singapore, 1838. The British Library, 14629.c.42 (3) (cat. 985 in Gallop 2019).

The seal of Tengku Abdul Jalil, lithographed on a typeset printed Malay letter from Thomas Church, Resident Councillor of Singapore, 1838. The British Library, 14629.c.42 (3) (cat. 985 in Gallop 2019).

Church’s initiative had little success. The Malay nobles were reluctant to have their children educated in a British establishment although “[f]ive hundred copies [of the letter] were printed and placarded over Singapore and Kampong Glam, and sent to no less than thirty different places round the coast and Borneo and Celebes by the nakhodas [captains] of trading vessels, but it led to no result”.5

Another seal in the catalogue from the line of Sultan Husain Syah is that of his successor. Following his death in 1835, Sultan Husain Syah was succeeded not by Tengku Abdul Jalil, whose mother Cik Wak was a commoner, but by Tengku Ali, the oldest son of his fourth wife, Tengku Perabu. She was of royal descent, being the granddaughter of Sultan Daud of Terengganu. At the time of his father’s death, Tengku Ali was just 11 years old. It was only in 1840, when he turned 17, that he was recognised as the legitimate successor to his father’s properties by the colonial government in Singapore.

Sultan Ali Iskandar Syah’s red ink seal, dating from 1840, is inscribed thus: al-wāthiq billāh al-Malik al-Mannān al-Sultan Ali Iskandar Syah ibn al-Sultan Husain Syah al-malik Johor sanat 1256, which means “He who trusts in God, the King, the Ever-Bestowing One, the Sultan Ali Iskandar Syah, son of the Sultan Husain Syah, the king of Johor, the year 1256” (1840/1).

Red ink seal impression of Sultan Ali Iskandar Syah, from a letter to Orfeur Cavenagh, Governor of the Straits Settlements, 30 May 1861. The British Library, MSS Eur. G.38/III, f. 115c (cat. 984 in Gallop 2019).

Red ink seal impression of Sultan Ali Iskandar Syah, from a letter to Orfeur Cavenagh, Governor of the Straits Settlements, 30 May 1861. The British Library, MSS Eur. G.38/III, f. 115c (cat. 984 in Gallop 2019).

Although Sultan Ali Iskandar’s seal inscription grandiloquently describes him as “the king of Johor”, this claim was short-lived for in 1855, he agreed to relinquish sovereign power to Temenggung Daeng Ibrahim of Johor in return for a pension as well as jurisdiction over the small district of Kesang-Muar. The seal he issued to his senior minister in Muar, Encik Bujal, bears the inscription al-wakil wa-al-wazir al-Sultan Ali Bujal bin Saadat sanat 1275, or “The deputy and the vizier of the Sultan Ali, Bujal, son of Saadat, the year 1275” (1858/9). The use of the term al-wakil recalls the seals granted by Sultan Ali’s grandfather, Sultan Mahmud Syah III, to his own officers of state.

The silver seal matrix of Encik Bujal, official of Sultan Ali, exhibited

in the Malay Heritage Centre in 2012 (cat. 991 in Gallop 2019).

The silver seal matrix of Encik Bujal, official of Sultan Ali, exhibited

in the Malay Heritage Centre in 2012 (cat. 991 in Gallop 2019).

| The Politics of the Johor Sultanate |

| The kingdom of Johor was established following the fall of Melaka to the Portuguese in 1511 when Mahmud Syah (also spelled as Shah), the exiled sultan, and his court fled southwards and took refuge along the Johor River. In 1699, Mahmud Syah II – the despotic last sultan of Johor who was descended from the Melaka royal line – was murdered by his nobles while being borne to the mosque on a dais (hence his posthumous title Marhum Mangkat Dijulang, which means “The late one who died as he was being carried aloft”). |

| As Mahmud Syah II had died without an heir, Bendahara Abdul Jalil, who was the most senior minister at the time, was proclaimed Sultan Abdul Jalil Riayat Syah IV of Johor. But he was in turn unseated by a Minangkabau prince, Raja Kecil of Siak, who claimed to be a posthumous son of Mahmud Syah II. Raja Kecil installed himself as Sultan Abdul Jalil Rahmat Syah of Johor and arranged for the killing of his predecessor. |

| In 1721, the son of Abdul Jalil Riayat Syah IV, Raja Sulaiman, accepted help from the Bugis to drive out Raja Kecil and, in return, the Bugis gained a permanent foothold in Johor. |

| Thenceforth, there were two seats of power within the sultanate of Johor, both located in the Riau Archipelago: the Malay sultan based on the island of Lingga as well as the Bugis viceroy, or Yang Dipertuan Muda, on the island of Penyengat. Two of the great officers of state advising the sultan – the Bendahara in Pahang and the Temenggung in Johor – effectively held sway within their own fiefdoms. |

| The last sultan able to lay claim to jurisdiction over the great kingdom of “Johor and Pahang and Riau and Lingga” was Mahmud Syah III. He reigned for over 50 years but died in January 1811 without naming which of his two sons – by different wives – was to succeed him. |

| As the older son Tengku Husain was away in Pahang fulfilling his father’s instruction to marry the daughter of the Bendahara, the powerful Bugis faction led by the Yang Dipertuan Muda, Raja Jafar, seized the opportunity to install the younger son, Tengku Abdul Rahman, who happened to be Raja Jafar’s nephew. This unilateral action was neither recognised by the Bendahara and Temenggung nor by Sultan Mahmud’s primary consort, Tengku Puteri, who refused to hand over the sacred regalia. |

| This was the succession dispute that Stamford Raffles took advantage of in 1819. Raffles installed Tengku Husain as sultan and the latter, thus empowered, signed a treaty with Raffles allowing a trading post to be set up on the island of Singapore. |

Seals Used by Women

Of the more than 2,000 seals recorded in the catalogue, only 17 belonged to women. The seal of Tengku Perabu – fourth wife of Sultan Husain Syah and the mother of Sultan Ali Iskandar Syah – is one of these. Her seal is a simple circle with an incised border and is inscribed: Tengku Perabu isteri Sultan Husain bin Mahamud Singkapura, or “Tengku Perabu, wife of Sultan Husain, son of Mahamud, Singkapura”. The terse composition, and non-standard spelling of Mahamud and Singkapura, suggest a less-than-accomplished scribe.

Tengku Perabu’s seal is found on a letter from Baboo Ramasamy, a school teacher in Singapore who had been granted a power of attorney by Sultan Ali in 1868. The letter, which claims authority in the name of Sultan Ali and his second son (and later nominated successor) Tengku Besar, is addressed to the Bendahara of Pahang and complains about boundary issues. Although undated, the letter mentions that the Governor of the Straits Settlements, Harry St George Ord, and the Chief Justice, Peter Benson Maxwell, had just left for Europe, which would place the letter around 1871.

Some insight into the character of Baboo Ramasamy is perhaps best revealed in a letter some two decades later, reproduced in The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (Weekly) on 28 September 1897. The letter is addressed to the editor of The Bangkok Times by “Baboo Ramasamay, now resident in Bangkok”, and signed “Baboo Ramsamy, Ex-Regent of Muar and Kesang and Lawful Heir to the Kingdom of Johore and its dependencies”.

In the course of a series of rhetorical questions defending the claims of the line of Sultan Husain Syah against the wiles of the Bendahara of Pahang and the Temenggung of Johor, Baboo Ramasamy raises his own case:

“Was I not in H[er] B[rittanic] M[ajesty]’s Court at Malacca, publicly adopted by H.M. Sultan Tuanku Purboo (widow and Dowager of H.M. the late Sultan Mahmood Hoosainshah Malik Al Johore and Ceder of the Island of Singapore to the East India Company) as her adopted son for ever and ever? Did Her Majesty not install me as the heir-at-law to the Kingdom of Johore and its dependencies, empowering me to put the Kingdom of Johore into proper order?… Did Her Majesty not command her son H.H. Sultan Allee to make over to me the territory of Muar and Kesang? Did H.H. Sultan Allee make over to me the territory and remain three days in the presence of the Punghulus and inhabitants?… Did I not reign over the said territory from 1868 to 1877 at a cost of more than 17,000 dollars?”6

Although Tengku Perabu is not mentioned in Baboo Ramasamy’s letter to the Bendahara of Pahang, he evidently had access to her seal which he used to support his claim of acting in the name of her son and grandson. In view of the unconventional wording and spelling on her seal, Tengku Perabu’s “adopted son for ever and ever” and his personal motivations may indeed have been the driving force behind its very creation.

Seal of Tengku Perabu, wife of Sultan Husain Syah and mother of Sultan Ali Iskandar Syah, stamped on a letter from Baboo Ramasamy to the Bendahara of Pahang, ca. 1871. Leiden University Library, KITLV Or. 171 (1) (cat. 988 in Gallop 2019).

Seal of Tengku Perabu, wife of Sultan Husain Syah and mother of Sultan Ali Iskandar Syah, stamped on a letter from Baboo Ramasamy to the Bendahara of Pahang, ca. 1871. Leiden University Library, KITLV Or. 171 (1) (cat. 988 in Gallop 2019).

Malay Seals of Arabs

One of the most intriguing seals from Singapore belonged to a Hadhrami7 merchant and ship owner, Syed Safi bin Ali al-Habshi. On 3 December 1865, he wrote to the Yang Dipertuan Muda of Riau, Raja Muhammad Yusuf, announcing his imminent appointment as Turkish consul:

“Paduka ayahda memaklumkan hal pada tahun ini paduka ayahda dapat perintah nanti sedikit hari lagi boleh dijadikan konsul.”8

[Your eminent father (i.e. Syed Safi) informs you that this year your eminent father received a command that in a few days’ time he may be appointed as consul.]

The letter, written in Jawi script and bearing the Syed’s seal, was most likely intercepted by the Dutch authorities or passed on to them by Raja Muhammad Yusuf. The document must have caused considerable concern as it was forwarded immediately to the Governor-General in Batavia by Elisa Netscher, the Dutch Resident in Riau.

A second letter from Syed Safi to Raja Muhammad Yusuf, written in Singapore on 6 January 1866 and bearing an even bigger and grander seal, was similarly sent to Batavia. Both letters are now held in the National Archives of Indonesia.

The two seals are of a calligraphic calibre not usually encountered in Southeast Asia and were, therefore, most likely made in Istanbul or elsewhere in the Ottoman realm. The larger one is inscribed in Arabic, with no fewer than four Qur’anic quotations:

“Min al-wāthiq bi-Rabbih al-Ghanī khādim al-shar‘ al-sharīf al-wafi wa-al-dawlat al-‘alīyat al-‘Uthmāniyah wa-al-dīn al-Hanafī al-Sayyīd al-Sāfī bin ‘Alī bin Muhammad bin Ahmad al-Habshī ‘Alawī ‘afā Allāh anhu sanat 1282 // bismillāh al-Rahmān al-Rahīm nasr min Allāh wa-fath qarîb hasbunā Allāh wa-ni‘ma al-Wakīl ni‘ma al-Mawlā wa-ni‘ma al-Nasīr ghufrānaka rabbanā wa-ilayka al-masīr.”9

[From he who trusts in his Lord, the Independent One, the servant of the noble and complete Law, of the masters and government of the Ottoman dynasty, and of the upright monotheistic faith, al-Sayyīd al-Sāfī bin ‘Alī bin Muhammad bin Ahmad al-Habshī ‘Alawī, may God forgive him, the year 1282 (1865/6) // “In the name of God, Most Gracious, Most Merciful” (Qur’an 27:30); “Help from God and a speedy victory” (Qur’an 61:13); “For us God suffices, and He is the best disposer of affairs” (Qur’an 3:173); “The Best to protect and the Best to help” (Qur’an 8:40); “(we seek) Your forgiveness, our Lord, and to You is the end of all journeys” (Qur’an 2:285).]

The first Ottoman consul in Singapore was Syed Abdullah bin Omar Aljunied, a Hadhrami Arab who was appointed on 31 December 1864. However, after only a few months in the post, he died in Mecca en route to Istanbul to pay his respects to the sultan. Although Syed Abdullah had named his brother Syed Junaid as vice-consul before he left, the latter was not confirmed as the new consul by the Ottoman authorities until 1882.

It is possible that in the period following Syed Abdullah’s death, there may have been some jockeying among Hadhrami notables in Singapore for the post of consul with Syed Safi being one of the contenders. However there is no mention of Syed Safi in official Ottoman documents and the only known mention of him appears in The Straits Times on 2 February 1861. The newspaper reported that Syed Safi, the owner of the ship Kangaroo that was used to transport pilgrims to the Hijaz, had tried to circumvent official limits on capacity by sending numerous extra passengers by tongkang (small cargo boats) to Karimun island, from where they could embark the ship lying outside of British jurisdiction.10 In any case, it seems as if Syed Safi’s ambitions of representing the Ottoman government in Singapore, as embodied in the beautiful seals he pre-emptively commissioned, were not to be realised.

Seal of Syed Safi bin Ali al-Habshi, on a letter to Yang Dipertuan Muda Raja Muhammad Yusuf in Pulau Penyengat, 6 January 1866; at 100 mm in diameter, this is the largest Malay seal in the catalogue. Arsip Nasional Republik Indonesia, Riouw 119 (cat. 1001 in Gallop 2019).

Seal of Syed Safi bin Ali al-Habshi, on a letter to Yang Dipertuan Muda Raja Muhammad Yusuf in Pulau Penyengat, 6 January 1866; at 100 mm in diameter, this is the largest Malay seal in the catalogue. Arsip Nasional Republik Indonesia, Riouw 119 (cat. 1001 in Gallop 2019).

British Malay Seals

The presence of an inscription in Arabic script is such a defining characteristic of seals used by Muslims all over the world that it tends to mask the fact that similar seals were also used by myriad other groups and ethnicities, including Christians in Ethiopia and Syria, Samaritans in Palestine, Hindu subjects of the Mughal emperor, European scholars of Arabic and Persian studies, and British officials of the East India Company, including in Southeast Asia.

The earliest known of these British Malay seals is that of Francis Light (1740–94) who, on behalf of the East India Company, negotiated with the Sultan of Kedah to establish a trading settlement in Penang in 1786. With the expansion of British colonial rule across the Malay Peninsula, seals with Jawi inscriptions – occasionally accompanied by elements in English – continued to be used by senior British officials.

In 1811, Raffles had a Malay seal made for Lord Minto, Governor-General of Bengal. There is no evidence, though, that Raffles himself ever used a Malay seal. A point of difference in usage can be noted: while traditional Malay seals can be characterised as personal official seals – each seal was issued in the name of an individual post holder – British Malay seals were seals of office and could be used by any incumbent.

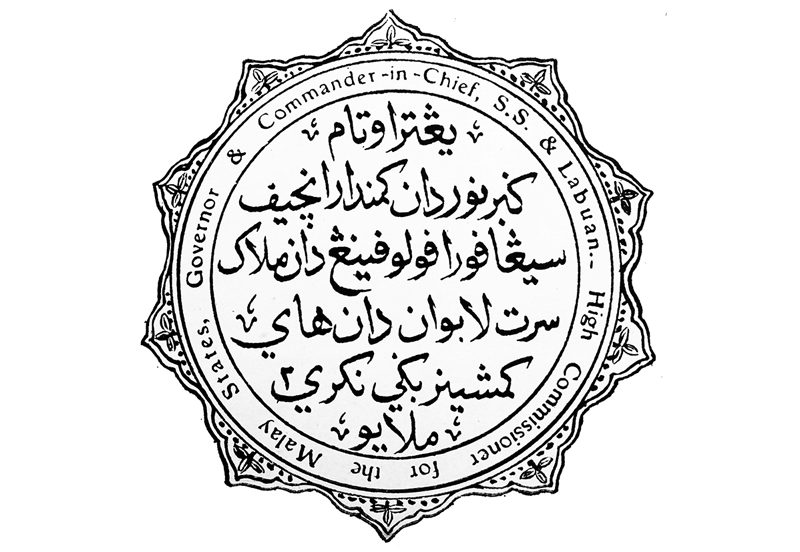

At least four Malay seals used from 1883 to 1927 by British governors of the Straits Settlements in Singapore are documented in the catalogue. Shown below is the seal used by at least three governors – Arthur Young (1911–20), Laurence Guillemard (1920–7) and Hugh Clifford (1927–30) – inscribed in Malay and English: Yang terutama Gabenor dan Komandar in Cif Singapura Pulau Pinang dan Melaka serta Labuan dan Hai Komisyiner bagi negeri2 Melayu // Governor & Commander-in-Chief, S.S. & Labuan, High Commisioner for the Malay States.

Malay seal of the British Governor of the Straits Settlements, on a letter from the Acting Governor to Sultan Sulaiman of Terengganu, 11 June 1925. Arkib Negara Malaysia Terengganu [1985] (cat. 998 in Gallop 2019).

Malay seal of the British Governor of the Straits Settlements, on a letter from the Acting Governor to Sultan Sulaiman of Terengganu, 11 June 1925. Arkib Negara Malaysia Terengganu [1985] (cat. 998 in Gallop 2019).

Traditional Malay seals were generally personal official seals. Behind the office of state named on each seal was an individual, whose predilections might be glimpsed in the form of name, family pedigree, date of accession to office and religious sentiment that they chose to have inscribed, as well as in the aesthetic choices affecting shape and decoration. However, with the introduction around the beginning of the 20th century of European-style seals of office – designed to be used by successive incumbents of a post – personal preferences began receding from view and we are merely left with the anonymising cloak of administrative authority.

|

| Annabel Teh Gallop’s Malay Seals from the Islamic World of Southeast Asia (2019) is published in Singapore by NUS Press in association with The British Library. The catalogue is available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library (Call no.: RSING 737.60959 GAL). It also retails at major bookshops in Singapore and overseas. |

Dr Annabel Teh Gallop is head of the Southeast Asian Collection at The British Library. She works on Malay and Indonesian manuscripts and has a particular interest in letters, documents, seals, and the illumination of Qur’ans and other Islamic manuscripts from Southeast Asia.

Dr Annabel Teh Gallop is head of the Southeast Asian Collection at The British Library. She works on Malay and Indonesian manuscripts and has a particular interest in letters, documents, seals, and the illumination of Qur’ans and other Islamic manuscripts from Southeast Asia.

REFERENCES

Buckley, C.B. (1984). An anecdotal history of old times in Singapore 1819–1867. Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 BUC-[HIS])

Ismail Hakki Kadi & Peacock, A.C.S. (2020). Ottoman-Southeast Asian relations: Sources from the Ottoman archives. Leiden: Brill. (2 vols.). (Not available in NLB holdings)

Taner, S.H. (2015). The first Turkish representatives in Singapore and Consul General Ahmed Ataullah Efendi. Singapore: Embassy of the Republic of Turkey in Singapore. (Available via Publication SG)

Winstedt, R.O., Khoo, K.K., & Ismail Hussein. (1992). A history of Johore (1365–1941). Kuala Lumpur: Printed for the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society by Academe Art & Printing Services Sdn. Bhd. (Call no.: RSING 959.511903 WIN)

NOTES

-

Gallop, A.T. (2019). Malay seals from the Islamic world of Southeast Asia: Content, form, context, catalogue. Singapore: NUS Press in association with The British Library. (Call no.: RSING 737.60959 GAL) ↩

-

Jawi is the modified Arabic script used to write the Malay language before it became displaced in popular use by a romanised script known as Rumi. ↩

-

Buckley, C.B. (1902). An anecdotal history of old times in Singapore (Vol. I, Frontispiece). Singapore: Fraser & Neave, Limited. (Accession no.: B02966444B). Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

How Singapore was founded: Signing of the treaty on February 6, 1819. (1937, October 25). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Johore claimant. (1897, September 28). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser (Weekly), p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Hadhramis inhabit the Hadhramaut region in Yemen. Hadhrami Arabs began migrating to Southeast Asia in great numbers from the mid-18th century onwards. The majority of Arabs in Singapore are descended from the Hadhramis. ↩

-

National Archives of Indonesia, Riouw 119. Letter in Malay from al-Sayyid al-Safi bin ‘Ali al-Habshi to Yang Dipertuan Muda Raja Muhammad Yusuf ibn al-marhum Raja Ali in Riau, 14 Rejab 1282 (3 December 1865). ↩

-

Untitled. (1861, February 2). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩