Milestones to the Metric System

Prior to the 1970s, Singapore used three different systems of weights and measures. Shereen Tay traces how we transitioned to the metric system.

A metric information stall set up at Circuit Road Market to educate residents during the Zonal Metric Educational Programme for the MacPherson constituency in 1979. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A metric information stall set up at Circuit Road Market to educate residents during the Zonal Metric Educational Programme for the MacPherson constituency in 1979. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

When people in Singapore reminisce about a time when life was simpler, it is unlikely that they would be referring to how they measured things. Until the 1970s, if you were buying cooking oil, for instance, you would be juggling three different systems of measurement: metric, Imperial and local.

Baey Lian Peck, Chairman of the Singapore Metrication Board during its existence from 1971 to 1981, recalled that at one point, “[cooking oil] was… sold in 36 different sizes and quantities, believe it or not. Rival brands [were] packed in gallons, fluid ounces, pounds, litres, kilograms, and kati”.1

The metric system, also known as the International System of Units (SI), uses units like the metre, the gram and the litre. Although this system is now commonly used worldwide, it was not the case in Singapore before the 1980s when the Imperial System reigned supreme. This meant using units such as inches, feet and miles for length; roods and acres for land area; fluid ounces, pints and gallons for volume; and ounces, pounds and stones for weight.2

Co-existing with these two systems were local units of measurement such as the kati, tahil and pikul for weight, and chupak and gantang for volume.

Why Metric?

The British Imperial System was introduced during the colonial era when measurements such as gallons, ounces, pounds, feet, inches and yards were used in the public and commercial sectors and in the markets. Local units of measurement such as chupak, gantang, tahil, kati and pikul were common in the retail trade. The metric system, on the other hand, was used rarely, mainly in specialised sectors such as engineering and science.3

The metric system was first adopted in France in the late 18th century and, over time, gained acceptance around the world (the United States being a major exception). In 1965, the United Kingdom announced that it would begin metrication, which sparked similar moves from other Commonwealth countries such as Australia and New Zealand. “[B]y 1969, 90 percent of Singapore’s external trade was with countries that were either already using the metric system or committed to conversion to the system,” said Baey.4

After Singapore gained independence in 1965, the government felt that moving to metric was necessary as the market for goods based on metric measurements would increase over time. The metric system also had other advantages: it was decimal-based and thus made computation easier. Children also found the metric system easier to learn compared with other systems of weights and measures. Commercially, industries would enjoy cost savings because they would not have to package the same product for different systems.5

In November 1970, the Ministry of Science and Technology submitted a White Paper recommending that Singapore convert to the metric system in carefully planned stages, starting with government departments, followed by the private sector.6

To “guide, stimulate and co-ordinate the metrication programme, particularly in the private sector”, the White Paper proposed that a Metrication Board be set up under the auspices of the Ministry of Science and Technology. Speaking in parliament while introducing the legislation to implement metrication, Toh Chin Chye, then Minister for Science and Technology, said:

“As Singapore’s economy is very much dependent on developments outside the country, we must move in step with the metricating world… It is impossible to expect housewives, amahs, or hawkers to change overnight their familiarity with customary units of measures… There must be a long period of… education to orientate the public towards the new system.”7

The Singapore Metrication Board was formed on 13 December 1970, with Baey as chairman. A businessman who joined the public service in his late 30s, Baey was then Chairman of the Trade General Committee of the Singapore Manufacturers’ Association and a member of several other boards. The Singapore Metrication Board included representatives from major economic, industrial and professional organisations to ensure that the decisions of the board reflected the consensus of all the organisations represented.8

Two bills were subsequently passed in February 1971 to formalise the use of the metric system in Singapore: the Metrication Bill (1970), which introduced the International System of Units (SI units), and the Weights and Measures (Amendment) Bill, which legalised the usage of SI units.9

| LOCAL UNITS OF MEASUREMENTS |

| The traditional units of weight in Malaya were tahil, kati and pikul. |

| 16 tahils = 1 kati 100 katis = 1 pikul |

| 1 tahil = 37.8 grams 1 kati = 600 grams (approximate) 1 pikul = 60 kilograms (approximate) |

| For volume, the traditional units of measurement were gantang (equivalent to 1 Imperial gallon or about 4.5 litres) and chupak. |

| 1 gantang = 4 chupak |

| REFERENCE |

| Lim, L. (2018, January 18). How catty and tael entered the English language, along with picul, mace and candareen – Asian weight measurements. South China Morning Post. Retrieved from South China Morning Post website. |

Public Sector: Miles Ahead

The public sector set the pace for adopting the metric system because any changes implemented by government departments and statutory bodies would cause ripple effects in the private sector and among the general population. All households in Singapore, for example, would be affected when the Public Utilities Board converted to the metric system when billing consumers for water usage. Similarly, the adoption of the metric system by the Housing and Development Board (HDB) would spur the construction industry to follow suit.10

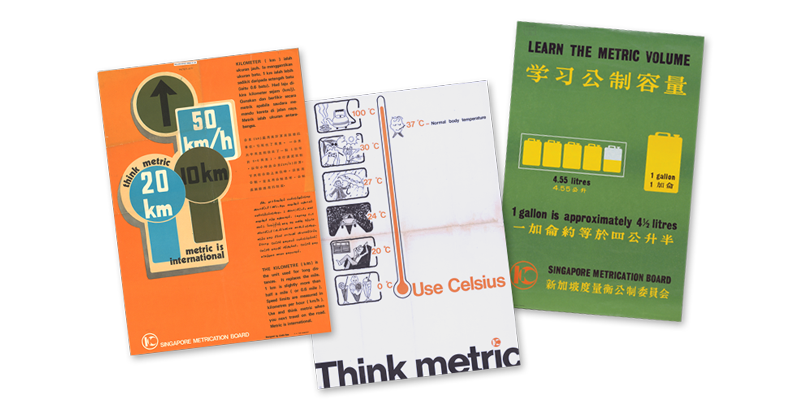

In the 1970s, the Singapore Metrication Board published a variety of posters with different themes to educate the public on the new metric system. Posters in four languages were displayed at government departments, schools, offices, factories, bus stops and even in coffee shops to reach out to as many people as possible. Think Metric, Use Celsius and Think Metric, Metric is International are from the collection of the National Library, Singapore (Accession nos.: B21228880I; B15913223D). Learn the Metric Volume is from the Singapore Metrication Board Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

In the 1970s, the Singapore Metrication Board published a variety of posters with different themes to educate the public on the new metric system. Posters in four languages were displayed at government departments, schools, offices, factories, bus stops and even in coffee shops to reach out to as many people as possible. Think Metric, Use Celsius and Think Metric, Metric is International are from the collection of the National Library, Singapore (Accession nos.: B21228880I; B15913223D). Learn the Metric Volume is from the Singapore Metrication Board Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The metrication of water usage and gas billing began in 1971. For road transport, speed limit signs in metric were put up along major expressways in 1972 and all new cars imported into Singapore came pre-installed with speedometers in metric units the following year.

Postal weight was metricated in 1972. In education, the metric system was used exclusively in the Primary School Leaving Examination for mathematics and science from 1973, while plans were made for secondary schools and tertiary institutions to switch to the metric system completely by 1975. By the end of 1973, most of the public sector had completed its conversion to the metric system, with the exception of those who had close workings with the private sector.11

The private sector generally supported metrication but there were challenges. Progress was slower for companies that had overseas parent headquarters or dealt primarily in international markets. Among the holdouts were companies in the oil rig building industry. Many were headquartered in the US and were, therefore, still using Imperial units. Civil aviation also lagged behind because it was dependent on the international regulatory bodies to convert to metric first.12

The most resistant industry was the retail trade which consisted of multiple players such as foreign exporters, importers, wholesalers, retailers and, most importantly, the general public. Because of the challenges, the Singapore Metrication Board decided to implement the changes in stages starting with a period of voluntary conversion followed by a mandatory changeover.13

Very early on, the board realised that the packaging of commodities had to be addressed. Surveys revealed that for some commodities such as cooking oil, the same item and quantity were sold in various sizes. This was confusing for consumers and also uneconomical for suppliers since the latter had to carry a wide range of the same stock. To address this, the board worked closely with respective industries to adopt a range of ideal sizes for consumer goods like soft drinks, milk powder, rice, ice-cream, bread, instant coffee, shampoo, toothpaste and detergent.14

But not all retail sectors were cooperative. Although the textile sector had agreed to use metric from 1972, the board noticed that they were still importing and selling fabrics by the yard in 1974. This was in part due to confusion and misinformation in the marketplace. In a 1976 news report, a stallholder in Tiong Bahru Market said customers believed that textiles sold by the metre were more expensive than those sold by the yard so they would rather shop at stalls still using Imperial units. The stallholder added, “They do not realise that one metre is three inches more than one yard. Since then I’ve reverted to tagging my goods in imperial units.”15 To assure the public that metrication would not lead to higher prices, the board produced conversion tables that rounded downwards instead.16 By 1978, a survey found that 93 percent of textile sellers were willing to sell in metres when requested by customers.

Vegetable sellers, however, were more recalcitrant. The same survey found that 30 percent of stallholders still refused to sell in kilograms. One of the main reasons was the unwillingness to learn, with one vegetable seller complaining, “I am too old to change and I think it is easier to use the daching.” Market stallholders, in general, also wanted to shift the responsibility of adopting metric to wholesalers and suppliers; nobody wanted to be the first to change.17

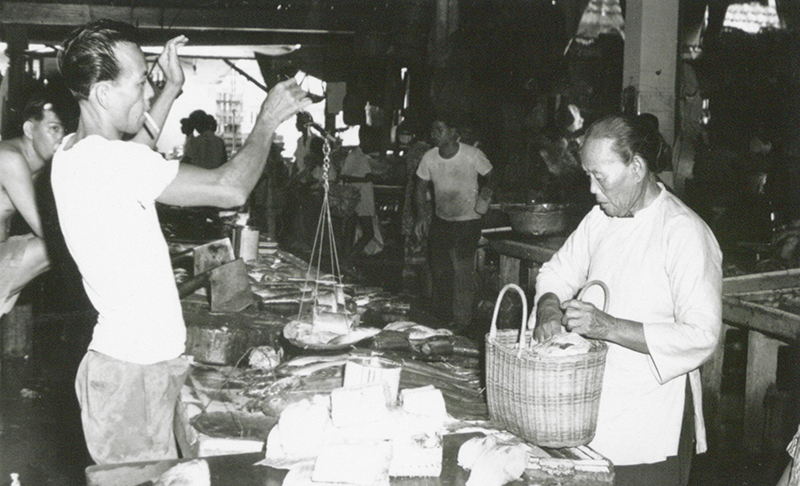

A fishmonger using a daching, 1960s. The daching was used to weigh items in pikul, kati and tahil. Metrication in Singapore made the traditional measuring scale obsolete. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A fishmonger using a daching, 1960s. The daching was used to weigh items in pikul, kati and tahil. Metrication in Singapore made the traditional measuring scale obsolete. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

It was also not easy convincing the general public to switch to the metric system. A survey conducted in 1975 showed that 52 percent of homemakers still had not heard of metres and kilograms. The majority of them were older, not well-educated and did not work. To protect the public from being scammed by dishonest retailers, the board and the Ministry of Science and Technology agreed to postpone the compulsory metrication of the retail industry, which was initially scheduled for 1 January 1976. Instead, retailers were required to sell in metric if customers requested to ensure that the public had more opportunities to practise using the metric system.18

| THE DEATH OF THE DACHING |

| The introduction of metrication in Singapore spelt the end of the Chinese daching.19 The daching allowed retailers to cheat easily because they could switch to using a lighter counterweight. And because the bar hung away from customers’ view, the buyer would not be able to see if the scale had been correctly calibrated. |

| Anticipating major resistance if they forced people to switch to the spring-based saucer scale, Baey Lian Peck, the Chairman of the Singapore Metrication Board, asked the Engineering Department at the University of Singapore to design a “fool-proof, non-cheating daching” based on the metric system. The metric daching set the bar horizontal when the correct measure was used so that the calibration was visible to consumers, and the counterweight was immovable. |

| In 1972, Baey arranged for the importation of 20,000 saucer scales and announced that retailers had to either use the saucer scale or the new metric daching. “As we expected, most of them opted for saucer scale,” he said. “This scale is easier to use than the cumbersome new metric daching that had furthermore been stripped of all the ‘advantages’ to the retailer. With this, the traditional Chinese daching died a natural death in Singapore without any legislation.”20 |

Public Education

The government mounted a public campaign on metrication. In 1976, the Singapore Metrication Board organised an Inter-School Metric Drama Competition for secondary students. The competition required participating teams to write and produce short plays based on a metric theme. A total of 31 plays in English, Chinese and Malay were submitted by 28 schools. Eventually, six winning plays were recorded by Radio and Television Singapore (RTS) and broadcast as a special programme on the eve of National Day in 1976.21

Riding on the success of the Inter-School Metric Drama Competition, in 1977, the board and RTS jointly produced Telemetric, a bilingual family television series to teach the metric system using quizzes and games. Twelve teams from registered societies and organisations took part. There were also contests and prizes for live audiences and home viewers.

From 1977 to 1980, the board conducted the Zonal Metric Educational Programme where staff visited constituencies and set up metric information stalls at selected markets to educate the public.22 The board also produced a free magazine in English and Chinese, Our Metric Way (available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library), and distributed it to households in various housing estates.

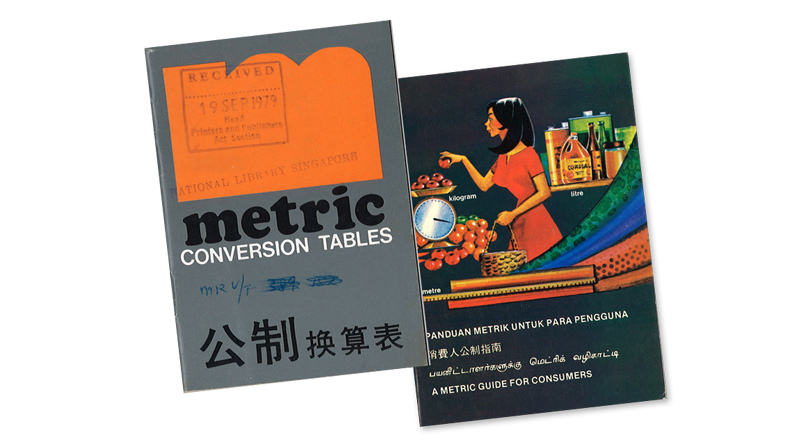

(Left) Metric Conversion Tables is a handy pocket-size booklet providing conversions for a variety of measurements, such as inches to millimetres, tahils to grams, gallons to litres, and even Fahrenheit to Celsius.

(Left) Metric Conversion Tables is a handy pocket-size booklet providing conversions for a variety of measurements, such as inches to millimetres, tahils to grams, gallons to litres, and even Fahrenheit to Celsius.(Right) A Metric Guide for Consumers provides illustrations to help consumers learn and visualise in metric. For example, 1 kilogram is equivalent to the weight of four blocks of butter, and two normal-size tomatoes weigh about 100 grams. It also teaches consumers how to read a metric daching and spring scale. Both publications were produced in the 1970s. Collection of the National Library, Singapore (Accession no.: B15913223D).

By 1978, surveys revealed that 79 percent of consumers knew about the metric system – a huge improvement compared with previous years. However, only 38 percent used metric measurements when shopping.23

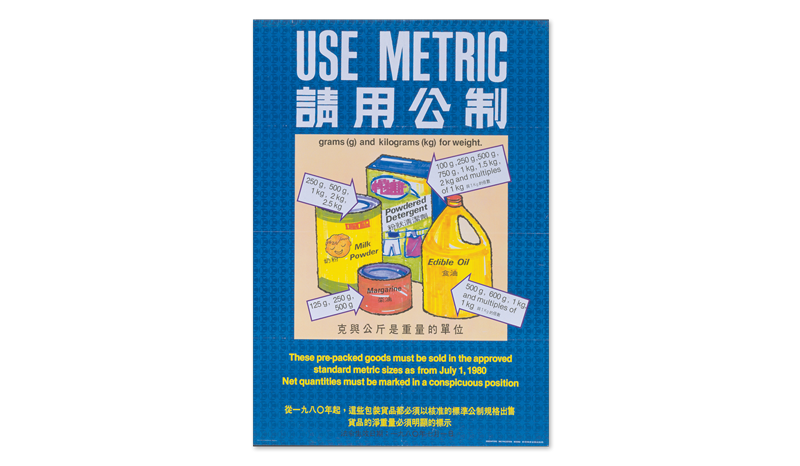

To complete the metrication process in Singapore, the board legislated standard sizes of commodities. This was introduced on 1 July 1979 under the Weights and Measures Act for butter, rice, cooking salt, plain wheat flour and granulated white sugar. The next year, this was extended to edible oil, margarine, milk powder and powdered detergent.24 On 1 April 1981, the Weights and Measures (Sale of Goods in Metric Units) Order came into effect, requiring the loose sale of textiles, groceries, bean sprouts, noodles, meat products, seafood products, fruits and vegetables to be conducted solely in metric.25

It’s Happening in Singapore: Weights and Measures is a 13-minute documentary produced by Radio and Television Singapore in May 1971 introducing the public to metric measurements and the benefits of the metric system. This programme can be viewed on Archives Online. Mediacorp Pte Ltd, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

It’s Happening in Singapore: Weights and Measures is a 13-minute documentary produced by Radio and Television Singapore in May 1971 introducing the public to metric measurements and the benefits of the metric system. This programme can be viewed on Archives Online. Mediacorp Pte Ltd, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The Yardstick of Success

After 11 years, the Singapore Metrication Board was dissolved on 31 December 1981, having converted most of the commercial, industrial and service sectors in Singapore to metric. Its functions were taken over by the Weights and Measures Office in 1982.26 Today, the Weights and Measures Office is managed by Enterprise Singapore, whose job is to ensure that a uniform and accurate system of weights and measures is used in Singapore.27

There were two areas that the Singapore Metrication Board did not convert to metric: existing property and land leases as these contracts spanned long periods of time, and Chinese medicine as the conversion might affect the calibration of herbs required for different uses.28

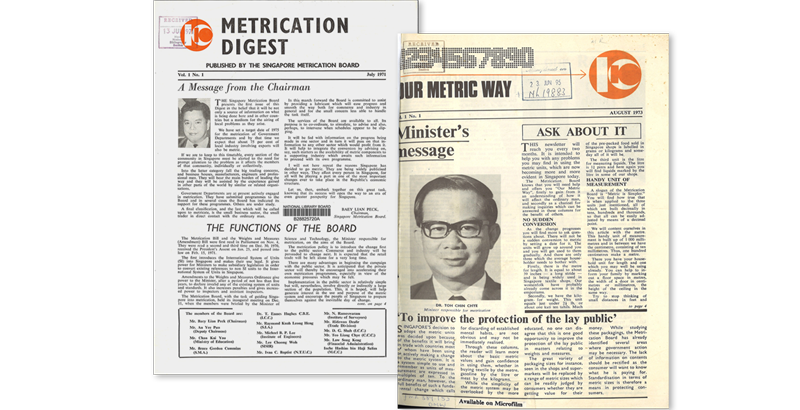

The Singapore Metrication Board produced two newsletters about metrication. Metrication Digest (1971) was printed primarily for the industrial, commercial and manufacturing sectors, providing up-to-date news on technical aspects such as standards, conversions and programmes for implementation. Copies were distributed to teachers, trade associations, professional institutes and chambers of commerce. Our Metric Way (1973–1981) was written in a simple and light-hearted manner with pictures, cartoons and articles to educate the general public on metrication. Copies were distributed to residents in housing estates across Singapore. Collection of the National Library, Singapore (Accession nos.: B28825720A and B17562025F).

The Singapore Metrication Board produced two newsletters about metrication. Metrication Digest (1971) was printed primarily for the industrial, commercial and manufacturing sectors, providing up-to-date news on technical aspects such as standards, conversions and programmes for implementation. Copies were distributed to teachers, trade associations, professional institutes and chambers of commerce. Our Metric Way (1973–1981) was written in a simple and light-hearted manner with pictures, cartoons and articles to educate the general public on metrication. Copies were distributed to residents in housing estates across Singapore. Collection of the National Library, Singapore (Accession nos.: B28825720A and B17562025F).

Although the metric system is widely used in Singapore today, remnants of the Imperial System remain. Advertisements for private properties often cite the area in square feet rather than square metres (although HDB flats use square metres). The screen sizes for televisions and laptops are still measured in inches instead of centimetres. Likewise, it is not uncommon to find measurements of clothing expressed in inches. Meanwhile, bars still serve beer in pints and, occasionally, yard glasses. All these cases, however, are very much the exception.

Looking back, Baey Lian Peck concluded that the measure of success of Singapore’s metrication was not whether it was implemented, but whether it caused disruptions and whether it brought about economic benefits to the country. On that score, he had no doubt. “I can proudly say we were quite successful in both these respects.”29

|

| A campaign poster produced in 1980. Singapore Metrication Board Collection, courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore. |

| FOR FURTHER RESEARCH… |

| The National Library and National Archives of Singapore are the custodians of Singapore’s published materials and government records. Primary material such as publicity posters, educational booklets and newsletters produced by the Singapore Metrication Board have been deposited with the two institutions and are available to researchers interested in this aspect of Singapore’s economic history. |

Shereen Tay is an Associate Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She is part of the team that oversees the statutory functions of the National Library Board, in particular, web archiving.

Shereen Tay is an Associate Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She is part of the team that oversees the statutory functions of the National Library Board, in particular, web archiving.

NOTES

-

Ooi, K.B. (2013). Serving a new nation: Baey Lian Peck’s Singapore story (p. 50). Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSING 959.5705092 OOI) ↩

-

Examples: for length, one foot = 12 inches, 3 feet = one yard; for volume, one ounce = 1/20 pint, one quart = two pints; for weight, one ounce = 1/16 of a pound, one stone = 14 pounds. ↩

-

Ministry of Science and Technology. (1970). Report on a study of the proposed conversion to the metric system in Singapore (p. 2). Singapore: Printed by Lim Bian Han, Govt. Printers. (Call no.: RSING 389.152 SIN); Singapore Metrication Board. (1976). 3 years of metrication in Singapore, 1971–1973 (p. 11). Singapore: Singapore Metrication Board. (Call no.: RSING 389.15095957 SIN) ↩

-

Ministry of Science and Technology, 1970, pp. 2–5. ↩

-

Ministry of Science and Technology, 1970, pp. 18–19; Toh: Change to metric no excuse for profiteering. (1970, November 5). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore Metrication Board, 1976, pp. 15–17; Metrication Board: Industrialist Baey is appointed chairman. (1971, January 6). Singapore Herald, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore Metrication Board, 1976, pp. 21–32; Singapore Metrication Board. (1974). 3 years along the road. Metrication Digest, 3 (7), p. 1. (Call no.: RSING 389.152 MD); Singapore Metrication Board. (1972). Annual report 1972 (p. 17). Singapore: The Board. (Call no.: RSING 389.1520615957 SMBAR) ↩

-

Ministry of Science and Technology, 1970, pp. 37–41; Ooi, 2013, pp. 49–50; Singapore Metrication Board. (1977). Annual report 1976/77 (p. 10). Singapore: The Board. (Call no.: RSING 389.1520615957 SMBAR); Singapore Metrication Board. (1978). Annual report 1977/78 (pp. 20–21). Singapore: The Board. (Call no.: RSING 389.1520615957 SMBAR) ↩

-

Traders surprised at metric warning. (1976, October 5). The Straits Times, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Metric warning to defiant sellers. (1978, August 18). The Straits Times, p. 9; Metric system: 80 pc know it but… (1978, September 25). New Nation, p. 3; Metric drive in markets leaves much to be desired. (1978, December 1). The Straits Times, p. 31. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The daching is a traditional weighing instrument consisting of a beam, a pan suspended on one end of the beam and a counterweight on the other end. ↩

-

Singapore Metrication Board. (1975). Metric postponement likely. Metrication Digest, 4 (12), p. 1. Singapore: Singapore Metrication Board. (Call no.: RSING 389.152 MD); Singapore Metrication Board. (1975). Metrication date postponed. Metrication Digest, 5 (1), p. 1. Singapore: Singapore Metrication Board. (Call no.: RSING 389.152 MD) ↩

-

Singapore Metrication Board. (1977). Annual report 1976/77 (pp. 12–13). Singapore: The Board. (Call no.: RSING 389.1520615957 SMBAR); Singapore Metrication Board. (1976). Metric Drama Competition finals at National Theatre in July. Metrication Digest, 5 (7), pp. 1, 4; Singapore Metrication Board. (1976). Metric plays on television. Metrication Digest, 5 (8), pp. 1, 4; Singapore Metrication Board. (1976). Drama competition results. Metrication Digest, 5 (9), pp. 1, 4. (Call no.: RSING 389.152 MD) ↩

-

Singapore Metrication Board. (1978). Annual report 1977/78 (pp. 26–28). Singapore: The Board. (Call no.: RSING 389.1520615957 SMBAR); Singapore Metrication Board. (1979). Annual report 1978/79 (p. 24). Singapore: The Board. (Call no.: RSING 389.1520615957 SMBAR) ↩

-

Singapore Metrication Board. (1978). Metric awareness up. Metrication Digest, 7 (2), p. 1. (Call no.: RSING 389.152 MD) ↩

-

Singapore Metrication Board. (1980). Annual report 1979/80 (pp. 2, 5). Singapore: The Board. (Call no.: RSING 389.1520615957 SMBAR); Singapore Metrication Board. (1981). Annual report 1980/81 (p. 4). Singapore: The Board. (Call no.: RSING 389.1520615957 SMBAR) ↩

-

Singapore Metrication Board. (1981). Annual report 1980/81 (p. 2). Singapore: The Board. (Call no.: RCLOS 389.1520615957 SMBAR); Singapore Metrication Board. (1981, February 20). Weights and Measures (Sale of Goods in Metric Units) Order 1981 [Press release]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website; Deadlines for going metric… (1981, February 17). The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Metric board to dissolve in year. (1981, February 13). The Straits Times, p. 34. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Enterprise Singapore. (2019, July 16). Weights and Measures Programme – Frequently asked questions. Retrieved from Enterprise Singapore website. ↩