The News Gallery: Beyond Headlines

There is more to news than meets the eye. Mazelan Anuar and Faridah Ibrahim give us the scoop on the National Library’s latest exhibition.

The “Behind Every Story” interactive zone showcases significant events from Singapore’s history to illustrate how news reporting can create different versions of reality.

The “Behind Every Story” interactive zone showcases significant events from Singapore’s history to illustrate how news reporting can create different versions of reality.

While rumours, falsehoods and hoaxes have been around since time immemorial, the advent of the internet and the proliferation of social media platforms have accelerated the speed at which such news is disseminated today.1 The need to sift fact from fiction is all the more important given the volume of information (and disinformation) people are presented with from both established and new sources of media.

With this in mind, the exhibition “The News Gallery: Beyond Headlines” was launched in March this year by the National Library Board. The exhibition, on level 11 of the National Library building, contains six zones, each focusing on a different aspect of the news landscape, including one on the history of newspapers in Singapore.

Singapore’s First Newspapers

Old newspapers are treasure troves of information and are a rich resource for academics, researchers and anyone with an interest in history. “Early Editions”, the first zone that visitors to The News Gallery will encounter, examines the origins of newspaper publishing in Singapore and the early players in the scene.

The printed newspaper as we know it today began proliferating in the 17th century with the rise of the modern printing press. It took another two centuries before Singapore’s first English-language newspaper hit the stands when the Singapore Chronicle and Commercial Register rolled off the press on 1 January 1824. Francis James Bernard, the son-in-law of Singapore’s first Resident, William Farquhar, was its editor.2

In 1835, a second English newspaper called The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser3 (see text box below) entered the scene. In response, the Singapore Chronicle halved its price and advertising rates, but to no avail. Barely two years later, the Chronicle folded; its last issue was published on 30 September 1837. Eight years later in 1845, The Straits Times4 – the newspaper that most Singaporeans are familiar with and the longest-running daily broadsheet – was launched.

This zone of the exhibition also showcases non-English-language newspapers that were published in Singapore. These vernacular newspapers addressed and promoted the issues, concerns and interests of their respective communities. In the early years, Chinese-language newspapers such as Nanyang Siang Pau and Sin Chew Jit Poh were concerned with the affairs of China,5 while Tamil Murasu was the vanguard of the social reform movement that was taking place among Indians in Singapore.6 Similarly, early Malay newspapers such as Jawi Peranakkan7 and Utusan Malayu8 championed the causes of the Malay and Muslim communities in Singapore.

| THE SINGAPORE FREE PRESS AND MERCANTILE ADVERTISER |

| While there are a number of English-language newspapers in Singapore today, The Straits Times is, by far, the dominant paper. However, it was not always so. In fact, even though it is Singapore’s longest-running newspaper, The Straits Times was a latecomer to the scene. When it first appeared, the paper had to compete with an earlier newspaper: The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser. It was a tussle that lasted over a century. |

| The Singapore Free Press was Singapore’s second English-language newspaper and began publishing on 8 October 1835. The Free Press took its name from the abolition of the gagging act. Prior to 1835, every issue of a publication in Singapore had to be submitted to the government before it could be published.9 With the demise of the Singapore Chronicle in 1837, The Free Press remained unrivalled until The Straits Times was launched in 1845.10 |

| The Singapore Free Press remained in circulation until 1869. It was relaunched in 1884 and, in 1946, it was bought over by The Straits Times in a move to fend off competition from a newspaper that had been launched in 1914, The Malaya Tribune.11 In 1962, The Singapore Free Press was eventually merged with The Malay Mail and the new entity retained the Malay Mail name. |

| The Singapore Free Press is associated with a number of well-known names. It was originally set up by a group that included lawyer William Napier; architect George D. Coleman; Edward Boustead, the founder of Boustead and Company; and Walter Scott Lorrain, head of Lorrain, Sandilands and Company. It was relaunched in 1884 by Charles Burton Buckley (author of An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore 1819–186712), who was later joined by John Fraser and David Neave (the co-founders of Fraser & Neave). Walter Makepeace (later co-editor of One Hundred Years of Singapore13) was a reporter with the paper who rose to become its joint proprietor and editor. |

| The Singapore Free Press was also notable for its contributions to the Malay newspaper scene. In 1907, The Singapore Free Press set up Utusan Malayu14, the Malay edition of the newspaper. Utusan Malayu became the only Malay newspaper to be circulated in the Straits Settlements and Malay Peninsula after its rival, Chahaya Pulau Pinang, folded just a few months into 1908.15 |

| Under its first editor, Mohamed Eunos Abdullah, Utusan Malayu’s mission was to provide the Malay community with an intelligent and impartial view of Malaya and the world. |

| In 1921, the newspaper was sued for libel by Raja Shariman and Che Tak, assistant commissioners of police in the Federated Malay States. The heavy damages awarded against it proved to be financially crippling and Utusan Malayu ceased operations as a result.16 |

|

| The Singapore Free Press was set up by William Napier, a lawyer; George D. Coleman, the first superintendent of public works; Edward Boustead, founder of Boustead and Company; and Walter Scott Lorrain, head of Lorrain, Sandilands and Company. This is the masthead of the issue dated 19 November 1835. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. |

The Story Behind the Story

Fake news is by no means a new phenomenon, but the internet and the new media have added to its exponential rise in volume and enabled it to spread like wildfire, wreaking havoc on a global scale. This can take a multitude of forms: from dodgy websites and mobile phone text messages circulating unfounded rumours to posts on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook containing convincing but deceptive images. There are even insidious deepfake videos capable of tricking even news-savvy viewers into believing what they see. The factors that drive fake news are equally varied – from political propaganda, fraud and financial gain, hatred and malice to simply well-meaning but mindless and ignorant sharing of falsehoods.

One highlight of the exhibition is the “Fact or Fake?” zone which features examples of fake news drawn from real life, such as the supposed collapse of Punggol Waterway Terraces in Singapore, lynch mobs in India who were spurred to action by rumours of child abductions and organ harvesting, anti-immigrant disinformation during the Brexit referendum in the United Kingdom, and investment scams featuring prominent Singaporeans. The content is presented in a light-hearted manner through an interactive quiz to engage younger audiences, especially students.

While most credible journalists aim to report truthfully, the reality is that no news article – whether from the traditional or non-traditional media – is completely free from bias. The political affiliations of newspaper owners and the personal opinions of journalists and news editors, among other factors, come into play. It is common knowledge that in the end, readers will believe what they want to believe, or search for news that best reinforces their views and perceptions of the external world.

Look out for the interactive zone called “Behind Every Story” which highlights significant events from Singapore’s history to illustrate how news reporting can create different versions of reality for different readers. Various news articles, photographs and video footage have been combined into a multimedia showcase for visitors to learn about these events and to see how they were reported at the time.

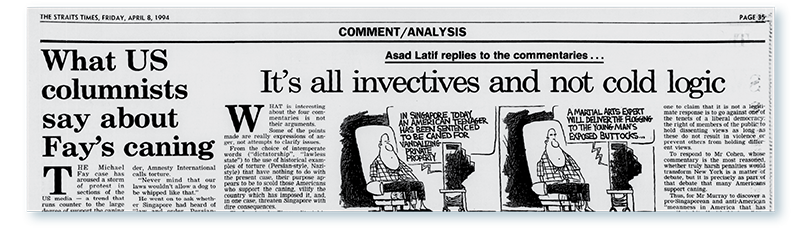

The events featured include the fall of Singapore in February 1942,17 the Maria Hertogh riots in 195018 and Singapore’s separation from Malaysia19 in 1965. More recent events include the Michael Fay saga in 199420 and the decision in 2005 to develop two integrated resorts in Singapore.21

At the height of the Michael Fay incident in 1994, The Straits Times deliberately published the opinions of US columnists alongside its own to rebut their arguments. The Straits Times, 8 April 1994. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

At the height of the Michael Fay incident in 1994, The Straits Times deliberately published the opinions of US columnists alongside its own to rebut their arguments. The Straits Times, 8 April 1994. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

On a Lighter Note

Newspapers are not merely about serious news – they also contain advertisements, entertainment stories, food reviews, photographs, recipes, puzzles, comics and even “Aunt Agony” columns. The zone “Extra! Extra!” showcases other interesting aspects of newspapers. The exhibits will be regularly updated to highlight different elements found in newspapers, with the first instalment on games and quizzes such as crossword puzzles, spot the ball and sudoku. Subsequent exhibits will look at photojournalism, cartoons and caricatures, and advertisements.

There is also a digital station featuring electronic newspaper resources available to library users. Visitors can browse and search past and current news on NewspaperSG, the National Library’s online archives of Singapore’s newspapers dating back to 1831 as well as other databases that provide access to local and international newspapers.

Mazelan Anuar is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. His research interests are in early Malay publishing and digital librarianship. He is part of the team that manages the Malay-language collection and NewspaperSG.

Mazelan Anuar is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. His research interests are in early Malay publishing and digital librarianship. He is part of the team that manages the Malay-language collection and NewspaperSG.

Faridah Ibrahim is Head of Reader Services at the National Library, Singapore, where she promotes the use of credible sources for research. Her research interests include information-seeking behaviours and pedagogical approaches.

Faridah Ibrahim is Head of Reader Services at the National Library, Singapore, where she promotes the use of credible sources for research. Her research interests include information-seeking behaviours and pedagogical approaches.

NOTES

-

Although in recent years, social media networks such as Facebook, YouTube and Instagram have made concerted efforts to stem the flow of fake news and misinformation on their sites. ↩

-

National Library Board. (2017). Singapore Chronicle written by Vernon Cornelius-Takahama. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

National Library Board. (2005, June 15). The Singapore Free Press written by Thulaja Naidu Ratnala. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

National Library Board. (2016, February 28). The Straits Times written by Stephanie Ho. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

Kennard, A. (1967, October 2). History of Chinese newspapers in Singapore. The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. Also see Lee, M. (2020, Jan–Mar). From Lat Pau to Zaobao: A history of Chinese newspapers. BiblioAsia, 15 (4). Retrieved from BiblioAsia website. ↩

-

Nirmala, M. (2013, February 9). A champion of Tamil causes who raised profile of Indians here. The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

National Library Board. (2016). Jawi Peranakkan written by Thulaja Naidu Ratnala. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

National Library Board. (2014). First issue of Utusan Malayu (1907–1921) is published. Retrieved from HistorySG website. ↩

-

National Library Board, 15 June 2005. ↩

-

National Library Board, 15 Jun 2005. ↩

-

National Library Board, 15 Jun 2005. ↩

-

Buckley, C.B. (1902). An anecdotal history of old times in Singapore (Vols. I and II). Singapore: Fraser & Neave, Limited. (Accession nos.: B02966444B; B02966440I) ↩

-

Makepeace, W., Brooke, G.E., & Braddell, R.S.J. (Eds.) (1921). One hundred years of Singapore: Being some account of the capital of the Straits Settlements from its foundation by Sir Stamford Raffles on the 6th February 1819 to the 6th February 1919 (Vols. I and II). London: John Murray. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.51 MAK) ↩

-

National Library Board, 2014. ↩

-

Roff, W.R. (1972). Bibliography of Malay and Arabic periodicals published in the Straits Settlements and peninsular Malay states 1876–1941: With an annotated union list of holdings in Malaysia, Singapore and the United Kingdom (p. 6). London: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RCLOS 016.0599923 ROF) ↩

-

National Library Board, 2014. ↩

-

See National Library Board. (2013, July 19). Battle of Singapore by Stephane Ho. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

See National Library Board. (2014, September 28). Maria Hertogh riots. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

See National Library Board. (2018, November). Federation of Malaysia written by Lee Meiyu. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

On 3 March 1994, American teenager Michael Fay was sentenced to four months’ jail, six strokes of the cane and fined S$3,000 for vandalism. His case was widely covered by the international media, especially in the US, who considered caning an archaic and barbaric act. The number of cane strokes was eventually reduced to four. Singapore-US relations remained strained for a number of years after the incident. See National Library Board. (2009). Michael Fay written by Valerie Chew. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website; New defining moments for Singapore (2018, September 24). The Straits Times. Retrieved from The Straits Times website. ↩

-

The two integrated resorts, which opened in 2010, are Marina Bay Sands and Resorts World Sentosa. See National Library Board. (2011). Marina Bay Sands written by Alvin Chua. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩