From Sea to Road: Building the Causeway

The foundation stone for the Causeway was laid 100 years ago on 24 April 1920. Building it was a major engineering feat at the time.

View of the Causeway from Singapore, c. 1970. Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

View of the Causeway from Singapore, c. 1970. Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

The Straits of Johor in the north of Singapore separates the Malaysian state of Johor at the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula from Singapore. It is 50 km in length, about 1.6 km wide and over 10 m deep for most of its length, with the depth being even greater towards the eastern end. At its narrowest point, the Johor Strait is a mere 600 m wide.

Native craft – such as the perahu, kolek, sampan and tongkang – were once a common sight in the Johor Strait. When conditions permitted, shallow-draught sailing craft, small boats and even steam launches navigated upstream from the estuaries along the strait. Before the Causeway opened in 1924, people from the Malay Peninsula travelled by sea directly to the town and harbour on the southern tip of Singapore island.

Early Connections

The Causeway was a product of the growing political and economic ties between Singapore and the Malay Peninsula. The strengthening of relations arose from the transformation of the Malayan economy – aided by growing British influence in the peninsula – from the latter half of the 19th century, which eventually led to the formation of the Federated Malay States (FMS) in 1896.1

A period of rapid economic growth soon followed, brought about by the production of rubber and tin. By the turn of the 20th century, Malaya – with its plantations, mining settlements, towns and ports – contributed close to 50 percent of the world’s rubber production and over 30 percent of its tin. The flurry of economic activities resulted in a pressing need to improve the transportation and communications infrastructure across the Malay Peninsula.

One of the first things the British administration did was to invest heavily in a network of railway lines across Malaya to connect the mining settlements and plantations with the nearest towns and seaports. With the formation of the FMS, various railway companies that had developed separately in different parts of Malaya were consolidated in phases under a single operator known as the Federated Malay States Railways (FMSR), which was established in 1906.

A new north-south trunk line linking the existing railway lines was also constructed and by October 1906, this line extended all the way to Gemas, a small town near the Negeri Sembilan-Johor border. The line from Gemas to the town of Johor Bahru, however, would not materialise until three years later in June 1909.

By the late 19th century, Singapore had become a major regional and international entrepot in addition to its role as a key steamship coaling station. The port benefited immensely from Malaya’s booming agricultural economy as well as the increasing demand for Malayan resources by the burgeoning industrial economies of the West. The rubber tyre and tin canning industries, in particular, saw rapid growth which in turn led to the development of a network of roads connecting Singapore town with plantations in the island’s outskirts.

Singapore benefited from Johor’s economic growth as it became the primary shipping port through which the latter’s produce was exported to the world. Likewise, Johor in turn benefited from the capital invested in the state by British and Chinese business interests in Singapore. With Johor’s growing prosperity and the increased opportunities for trade, travel and development, policy makers from both sides of the straits began to think of ways to improve the transportation infrastructure within their own territories and across the Johor Strait.

By Rail and then by Ferry

In 1899, the Colonial Secretary of the Straits Settlements,2 James Alexander Swettenham, resurfaced an old motion at the Straits Settlements Legislative Council meeting: he suggested constructing a railway line across Singapore that would link the town and port to the Johor Strait. The idea was first raised in 1874 by Governor Andrew Clarke and then in 1889 by Governor Cecil Clementi Smith. On both occasions, however, the plan was shelved due to the high projected costs and limited profitability.

This time, prominent community leader Lim Boon Keng, who represented the Chinese business community in Singapore’s Legislative Council, was instrumental in convincing the council to approve the plan. Seconding Swettenham’s motion, Lim declared: “If I can rely on information given me by Chinese traders, I think the railway will be of the greatest benefit.”3

In 1900, the Colonial Engineer’s Department began constructing the railway. The main track, linking Tank Road in Singapore town and Woodlands in the north, opened in April 1903. Extension tracks connecting the main line to the wharves in Pasir Panjang would not be completed until 21 January 1907.4

Bukit Timah Railway Station along the Singapore-Kranji Railway line, 1900s. The line would eventually link up with the Causeway. Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Bukit Timah Railway Station along the Singapore-Kranji Railway line, 1900s. The line would eventually link up with the Causeway. Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

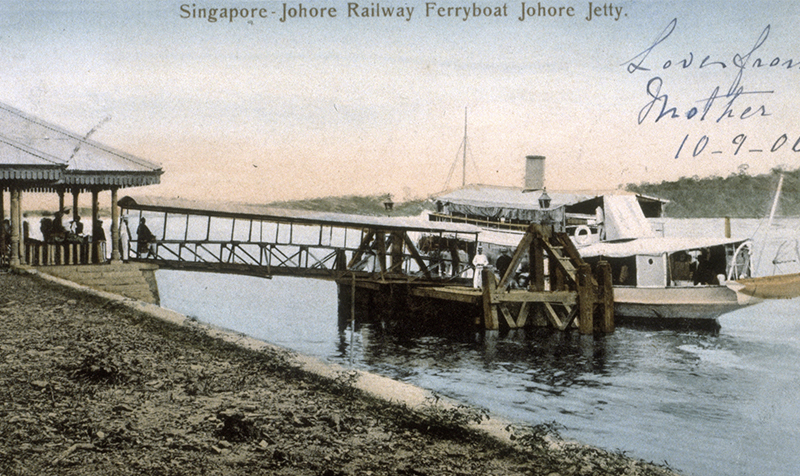

Although the railway was named Singapore-Kranji Railway, it actually terminated in Woodlands. Passengers disembarked at Woodlands Station and then boarded one of two steam-powered ferry boats – aptly named Singapore and Johore – across the Johor Strait to Johor Bahru and vice versa. Each ferry had a capacity of 160 passengers. By 1912, a third ferry named Ibrahim was deployed.

The ferry boat docked at the jetty in Johor Bahru, 1906. Such boats were used to transport people and goods across the straits between Singapore and Johor before the Causeway was built. Arshak C. Galstaun Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The ferry boat docked at the jetty in Johor Bahru, 1906. Such boats were used to transport people and goods across the straits between Singapore and Johor before the Causeway was built. Arshak C. Galstaun Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Initially, goods wagons were hitched to the passenger trains travelling on the Singapore-Kranji Railway but the increase in passengers and general goods traffic soon necessitated the use of separate trains for passengers and goods. In its first year of operation, the railway line carried a total of 426,044 passengers. Revenue from general goods traffic increased more than threefold, from 1,833 Straits dollars in 1903 to 6,266 Straits dollars in 1904.5

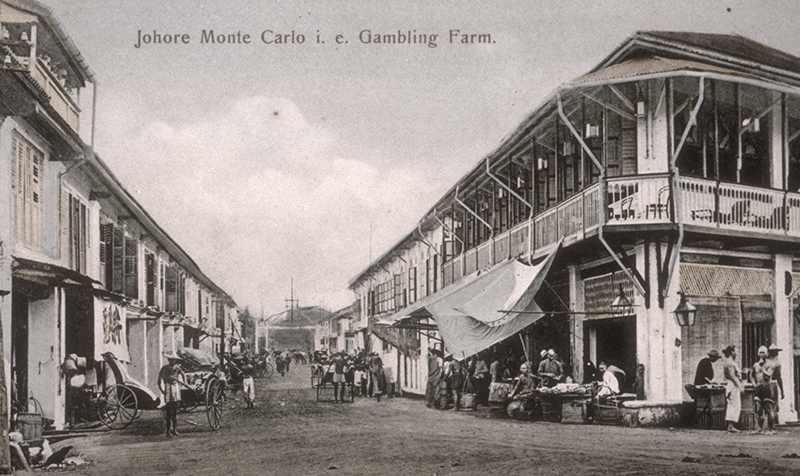

Passenger traffic was heaviest on Sundays when residents in Singapore travelled to Johor Bahru – regarded as a weekend resort town and a Monte Carlo of sorts – to try their luck at one of the many gambling farms, as they were called then, across the border. To entice customers, the proprietors of these gambling farms offered to pay their return fares from Johor on Sundays. Packed third-class train cabins returning to Singapore on Sundays were a common sight in the early 1900s.6

The “Monte Carlo” gambling farm in Johor Bahru, 1900s. On Sundays, residents in Singapore

travelled to Johor Bahru to try their luck at one of the many gambling farms there. To entice customers, proprietors of these gambling farms paid their return train fares from Johor on Sundays. Gwee Thian Hock Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The “Monte Carlo” gambling farm in Johor Bahru, 1900s. On Sundays, residents in Singapore

travelled to Johor Bahru to try their luck at one of the many gambling farms there. To entice customers, proprietors of these gambling farms paid their return train fares from Johor on Sundays. Gwee Thian Hock Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

By 1909, the passenger and goods train and ferry system was under increasing pressure to keep pace with the rapidly growing movement of people and goods across the Johor Strait. An early attempt to alleviate cross-straits congestion was introduced in mid-1909 with the use of “wagon-ferries”. Also known as trainferries, these were barges specially outfitted with railway tracks, each capable of transporting up to six train carriages by sea to connect with the railway lines at either end. They complemented the passenger ferry boats and, for the first time, allowed the seamless carriage of goods from ferry to railway without having to unload and load goods.

The wagon-ferry jetty in Johor Bahru, 1919. Wagon-ferries were barges specially outfitted with railway tracks, each capable of transporting up to six train-carriages across the sea. They complemented the passenger ferry boats. Courtesy of National Archives of Malaysia.

The wagon-ferry jetty in Johor Bahru, 1919. Wagon-ferries were barges specially outfitted with railway tracks, each capable of transporting up to six train-carriages across the sea. They complemented the passenger ferry boats. Courtesy of National Archives of Malaysia.

From Wagon-Ferry to the Causeway

While the wagon-ferries were generally regarded as a successful step forward in improving the transportation of goods across the Johor Strait, demand for its services soon outstripped capacity. Between 1910 and 1911 alone, the volume of goods conveyed across the strait increased from 19,278 tons to 30,142 tons. Correspondingly, there were 1,541 wagon-ferry trips in 1911, increasing to 1,993 trips in 1912, with numbers projected to rise sharply in the years ahead.7

The pressure on the ferry service intensified when motor vehicles became more popular in Malaya in the 1910s. In 1913, wagon-ferries began transporting motor vehicles – together with the driver and passengers – in open railway trucks protected by tarpaulin sheets during the trip across the Johor Strait. In addition to traffic volume, the escalating costs of maintaining the ferries raised concerns about their long-term viability. As early as February 1912, the FMSR management cited the high cost of operating the ferries (to the tune of 53,750 Straits dollars annually) as an important reason for seeking an alternative. Eventually, governments on both sides of the Johor Strait agreed that a more effective mode of cross-straits transportation had to be found.

In her book To Siam and Malaya in the Duke of Sutherland’s Yacht ‘Sans Peur’, published in 1889, British writer Mrs Florence Caddy describes her journey along the Straits of Johor and arrival in Johor on 4 March 1888. She notes that the Sans Peur passed through the “eastern passage” – an apparent reference to the Johor Strait – from Singapore to the Malay Peninsula, before dropping anchor at Johor Bahru, with the Malay village of Kranji visible on the Singapore side of the strait.

The jetty where she landed had a “sea-side portico”, which had been built for the reception of the young Prince of Wales’ visit to Johor in 1882. She also writes of her trip to Singapore (and back) the next day, crossing the strait in the sultan’s steam launch to land at Kranji before travelling to Raffles Hotel and Istana Tyersall (Tyersall Palace) in a “four-inhand” horsedrawn carriage. Her jottings in the book have helped the present-day reader identify jetties and landings used in early crossings of the strait.

A number of prominent foreign dignitaries and royalty also experienced crossing the Johor Strait in the 1880s and 90s – notably the Prince of Wales in 1882, the Duke of Sutherland in March 1888, the Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria in April 1893, King Chulalongkorn of Siam in May 1896 and Prince Henry of Prussia in February 1898.

The suggestion by FMS Director of Public Works, W. Eyre Kenny, to build a causeway by dumping tons of rock and rubble across the strait soon gained traction. This proposal was preferred over a bridge as the price of steel and the cost of maintaining a bridge were deemed prohibitive. The foundation for the rubble causeway would be easier to lay over the soft “white and pink clays” at the proposed site, and constructing an opening for ships to pass through would not be overly complicated.

Moreover, there was an ample and inexpensive source of granite available from quarries at Pulau Ubin and Bukit Timah in Singapore. In 1918, detailed plans drawn up by consultant engineers Messrs Coode, Matthews, Fitzmaurice & Wilson were presented to the FMS, Straits Settlements and Johor governments. In 1919, the Straits Settlements government formally approved the Causeway project.8

Engineering the Causeway

The Causeway project was considered technically challenging by the standards of the time and deemed one of the “greatest engineering works” undertaken in the Far East. Construction was estimated to take between four and five years, and would require the labour of more than 2,000 workers – both locals and Europeans – as well as millions of tons of stone and other building materials.9

The proposed Causeway would be 3,465 ft long (1,056 m) and 60 ft wide (18.3 m),10 and equipped with two lines of metre-gauge railway tracks and a 26-feet wide (8 m) roadway, with provisions for the laying of water mains at a later date. The Causeway would also be equipped with a lock channel to allow the passage of small vessels, an electric liftbridge, water pipelines and flood gates to manage water flow.

Tidal studies carried out earlier in 1917 revealed that the construction of the Causeway would effectively separate the Johor Strait into two tidal compartments and give rise to differences in water levels on either side of the structure once it was completed. As a result, the consultant engineers came up with the ingenious idea of incorporating a set of double flood gates in the lock channel in order to control the tides alternating on either side of the Causeway.

On 30 June 1919, the contract to construct the Causeway was awarded to Messrs Topham, Jones & Railton Ltd. of London, an engineering firm that had successfully carried out several major public projects in Singapore, including King’s Dock at Keppel Harbour and Empire Dock at Tanjong Pagar. The company had a team of experienced engineers and workmen, and all the necessary tools and equipment for the job.

Construction of the Causeway commenced in August 1919 and was scheduled to be completed in 1924, taking five years in all. Work began with the excavation of the lock channel, which was located at the Johor side in order to minimise disruption to the ferry services. The total cost of the project, estimated at 17 million Straits dollars, was borne by the FMS, Johor and Straits Settlements governments.

Laying the Foundation Stone

With work on the Causeway progressing smoothly, a ceremony to mark the laying of its foundation stone was held. On 24 April 1920, the ceremony took place on board the steam yacht Sea Belle anchored in the middle of the Johor Strait. It began with a procession by Johor religious officials bearing vessels containing ceremonial waters, incense and prayer sheets for the occasion. Upon the arrival of Sultan Ibrahim of Johor, the state anthem was played, followed by a short prayer by the mufti of Johor.

Governor of the Straits Settlements and High Commissioner of the FMS Laurence Nunns Guillemard – who officiated the ceremony – and his wife were ferried to the Sea Belle where they were received by Sultan Ibrahim. The ceremony commenced with prayers before Guillemard was invited to pull a silken cord, activating the first load of rubble comprising crushed stone and granite from a barge into the Johor Strait. A second barge then released its load of rubble before the ceremonial waters were poured into the strait. A five-gun salute marked the end of the ceremony.11

This ceremony took place amid a period of economic boom in Malaya. Prices of Malaya’s main exports in the overseas market, such as rubber and tin, had reached record levels in the first half of 1920. In the second half of the year, however, a sudden worldwide economic depression took a severe hit on the Malayan economy, lasting until the latter part of 1922. Given the bleak economic conditions, the Causeway project came under increasing public scrutiny and criticism, and was nearly abandoned by the FMS and Straits Settlements governments.

Fortunately, the project was not aborted and in June 1921, enough rubble had been deposited at the Johor end, allowing the construction of the Causeway’s superstructure – eventually comprising a two-way road as well as a railway line running alongside – to begin from both the Singapore and Johor sides.

The year 1923 was a milestone in the history of the Causeway. For the first time, a seamless road and railway link now connected Singapore and Johor. When the Causeway rail link first opened to goods trains on 17 September,12 the wagon-ferry service between Johor Bahru and Woodlands was withdrawn. Two weeks later on 1 October, the FMSR opened the railway line for public use, ending the cross-strait passenger steam-ferry service that had been in operation for more than a decade.

The first passenger train to cross the Causeway was the night mail, which left Kuala Lumpur on 30 September 1923 and arrived at Tank Road Station in Singapore at 7.41 am on 1 October. The Straits Times described it as “a big train, including twelve bogey carriages and forming an imposing display of rolling stock for the auspicious occasion”.13 The daily schedule included a day mail and a night mail train to and from both destinations. On 1 October, the Johor Causeway Toll was introduced for both passenger and goods traffic conveyed over the Causeway, replacing the earlier ferry charges.

A Brilliant Opening

The construction of the Causeway was officially completed on 11 June 1924, three months ahead of the stipulated date. The opening ceremony, which took place on 28 June 1924 in Johor Bahru, was attended by more than 400 guests from the FMS, Straits Settlements and Johor. It was a lavish affair presided by Laurence Nunns Guillemard – in his capacity as the FMS High Commissioner and Straits Settlements Governor – in the presence of Sultan Ibrahim of Johor. Guests included Malay nobility, prominent government officials as well as “gentlemen in the banking and commercial worlds”.14

The completed Causeway viewed from Woodlands, June 1924. Courtesy of National Archives of Malaysia.

The completed Causeway viewed from Woodlands, June 1924. Courtesy of National Archives of Malaysia.

A public holiday was declared in Johor Bahru, and train and pedestrian traffic around the Causeway was halted to dignify the occasion. Guests from Singapore and the FMS were conveyed by special trains to Johor Bahru Station in the morning.

In his speech, Guillemard recalled the engineering feat that made the construction of the Causeway possible, and paid tribute to the men who were involved in its planning and construction:

“Your Highness, your Excellency, ladies and gentlemen, the duty which has fallen to my lot this morning is both a pleasure and an honour. I feel it a great honour to take part in this ceremony. In our time we have seen the miracles of yesterday become the commonplaces of today, but this great engineering feat ranks high even in an age of high achievement. It stands before you as a monument to the skill and patience of those who made it and the foresight of those who planned… I have much pleasure in declaring the Causeway open.”15

Guillemard then severed the silken cord stretched across the entrance to the Causeway, using a specially commissioned golden knife presented to him by Sultan Ibrahim. After the Johor state anthem was played to conclude the ceremony, Guillemard turned to the sultan and said:

“I thank your Highness, and hope that you will accept this pencil as a memento of this occasion. It is an English superstition that the gift of a knife of any kind, if accepted without a counter-gift, leads to the severance of the friendship between donor and recipient.”16

The opening ceremony of the Causeway on 28 June 1924 was a lavish affair presided by Laurence Nunns Guillemard, Governor of the Straits Settlements and High Commissioner of the Federated Malay States. On the governor’s left is Sultan Ibrahim of Johor with his left hand on the hilt of his sword. Courtesy of National Archives of Malaysia.

The opening ceremony of the Causeway on 28 June 1924 was a lavish affair presided by Laurence Nunns Guillemard, Governor of the Straits Settlements and High Commissioner of the Federated Malay States. On the governor’s left is Sultan Ibrahim of Johor with his left hand on the hilt of his sword. Courtesy of National Archives of Malaysia.

After the event, an entourage comprising Guillemard, Sultan Ibrahim, and several Malay rulers and senior British officials were driven across the Causeway to Singapore in a convoy of 11 motorcars for lunch at Government House, thus opening the Causeway for public use.

The Causeway’s opening marked an important milestone in regional communications and transportation. It established, for the first time, direct and uninterrupted rail communications from Singapore and through the Malay Peninsula to Bangkok, Siam (now Thailand).

The opening of the Causeway’s roadway also marked the rise of motor transport as an increasingly significant means of transportation between Singapore and Malaya. What surprised its planners, however, was the rapid growth in vehicular traffic that soon outpaced the railway as the preferred mode of cross-straits transportation.

Above all, more than a physical link, the Causeway is a fitting symbol of the close ties and shared history that bind Singapore and Malaysia.

The Causeway became a scene of action during World War II. On 8 December 1941, troops of the Japanese 25th Army – under the command of Lieutenant-General Tomoyuki Yamashita – landed in southern Thailand and Kota Bahru in northern Malaya. This was followed by an air raid over Singapore a few hours later when the first bombs were dropped on the island.

On 31 January 1942, British troops set off two explosions on the Causeway. The first wrecked the lock’s lift-bridge, while the second caused a 70-foot gap in the structure. This photo shows Japanese troops crossing the Causeway into Singapore after constructing a girder bridge over the gap. Lim Kheng Chye Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

On 31 January 1942, British troops set off two explosions on the Causeway. The first wrecked the lock’s lift-bridge, while the second caused a 70-foot gap in the structure. This photo shows Japanese troops crossing the Causeway into Singapore after constructing a girder bridge over the gap. Lim Kheng Chye Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.With air superiority established, Japanese forces swiftly advanced down the Malay Peninsula and reached Johor in mid-January 1942. Left with little choice, on 27 January, the British commander Lieutenant-General Arthur Percival ordered his forces to retreat. After the British and Commonwealth forces had crossed the Causeway from Johor to Singapore in the early hours of 31 January 1942, the order was given to blow it up. There were two great explosions: the first wrecked the lock’s liftbridge, while the second caused a 70-foot gap in the structure. The pipeline carrying water to Singapore was also severed.

Within weeks of Japan’s surrender on 15 August 1945, the British returned to begin the post-war reconstruction of Singapore and Malaya. They replaced the girder bridge that the Japanese had constructed over the gap with two British Bailey bridges. Railway tracks across the Causeway were also re-laid, and the bridge resumed its role of facilitating travel and trade between the two territories.

|

| This essay was condensed from The Causeway (2011), jointly published by the National Archives of Malaysia and the National Archives of Singapore. It is available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries (Call nos.: RSING 388.132095957 CAU and SING 388.132095957 CAU). |

| All images from the National Archives of Malaysia reproduced in this essay are taken from this book. |

NOTES

-

The FMS, which was established in 1895, was a federation of four British protected states comprising Selangor, Perak, Negeri Sembilan and Pahang, with Kuala Lumpur as its capital. ↩

-

The Straits Settlements, comprising Penang, Melaka and Singapore, was formed in 1826 by the British colonial authorities. ↩

-

Straits Settlements Legislative Council. (1899, August 22). Proceedings of the Legislative Council of the Straits Settlements with appendix (p. B 114). Singapore: Government Printing Office. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Singapore and Kranji Railway. (1907, January 21). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Wright, A., & Cartwright, H.A. (Eds.). (1989). Twentieth century impressions of British Malaya: Its history, people, commerce, industries, and resources (p. 184). Singapore: G. Brash. (Call no.: RSING q959.9 TWE) ↩

-

Wright & Cartwright, 1989, p. 285. ↩

-

Johore Annual Reports 1910–1913 (Microfilm no.: CO 715/1). Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore; Federated Malay States Railways Report for the Year 1912 (Not available in NLB holdings). ↩

-

Federated Malay States. (1917, November 13). Proceedings of the Federal Council of the Federated Malay States for the year 1917 (p. B57). Singapore: Government Microfilm Unit. (Microfilm no.: NL6390); The National Archives (United Kingdom). (1917, November 7). Extract of letter from Messrs Coode, Matthews, Fitzmaurice & Wilson to Crown Agents (p. 267) (Accession no.: CO 273/462). Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

The Causeway. (1924, June 27). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Between 1964 and 1988, the Causeway was widened three times to accommodate the increased trade volume and human traffic between Malaysia and Singapore. It was further widened between 1989 and 1991. ↩

-

Johore Causeway. (1920, April 26). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Federated Malay States Report for the Year 1923. ↩

-

Johore Causeway. (1923, October 1). The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewpaperSG. ↩

-

Johor Causeway. (1924, May 27). The Straits Times, p. 9; The Johore Causeway. (1924, July 5). Malayan Saturday Post, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Causeway. (1924, June 28). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 28 Jun 1924, p. 9. ↩