Early Printing in Myanmar and Thailand

In the second of two essays on the history of printing in mainland Southeast Asia, Gracie Lee recounts how Christian missionaries brought printing technology to Myanmar and Thailand.*

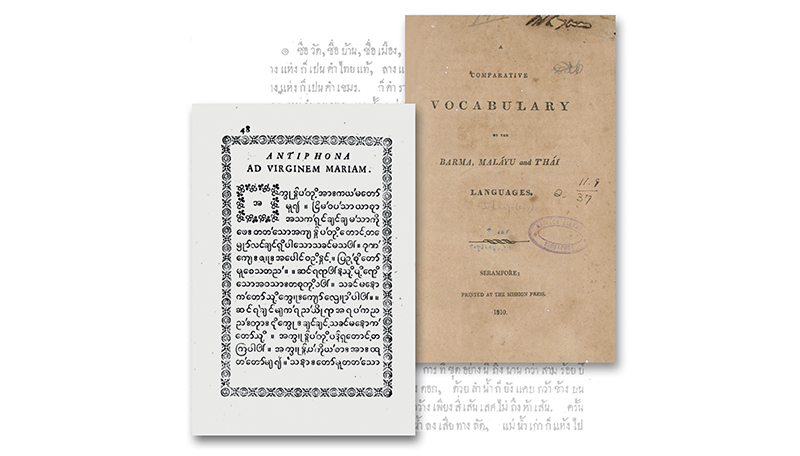

(Left) Alphabetum Barmanum (1776) by Father Carpani is widely regarded as the oldest extant printed book in Burmese. The Catholic prayer the Ave Maria is shown here. Retrieved from Internet Archive website. (Right) A Comparative Vocabulary of the Barma, Maláyu and T’hái Languages (1810) by the Scottish linguist John Leyden. This is one of the earliest printed works in Burmese published by the Serampore Mission Press. The book also contains Jawi script. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession no.: B03013686E)

(Left) Alphabetum Barmanum (1776) by Father Carpani is widely regarded as the oldest extant printed book in Burmese. The Catholic prayer the Ave Maria is shown here. Retrieved from Internet Archive website. (Right) A Comparative Vocabulary of the Barma, Maláyu and T’hái Languages (1810) by the Scottish linguist John Leyden. This is one of the earliest printed works in Burmese published by the Serampore Mission Press. The book also contains Jawi script. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession no.: B03013686E)

The story of modern printing in Myanmar and Thailand shares some similarities with each other. In both countries, printing technology arrived through the work of missionaries. This was before local and colonial governments, and commercial publishers began establishing their own printing presses. Catholic and Protestant missionaries developed typefaces appropriate to Burma and Thailand and shipped over printing presses so that religious literature could be published in the local languages. This, in turn, seeded the development of printing in other areas.

Myanmar

The earliest printed works in Burma (now Myanmar) emerged with the arrival of Catholic missionaries in the early 18th century. In 1773, Father Percoto, an Italian priest residing in Burma, entrusted his manuscripts to his co-worker, Father Melchior Carpani, and instructed him to procure a printing press and Burmese fonts from Rome.

In Rome, Father Carpani published Alphabetum Barmanum (1776), a primer based on Father Percoto’s manuscript, with the Propaganda de Fide press, the missionary arm of the Roman Catholic Church. This is regarded as the oldest extant Burmese printed book. The work, in Latin and Burmese, contains an introduction by Father Carpani and sections devoted to the Lord’s Prayer, the Ave Maria, the Apostle’s Creed, an antiphon of the Virgin Mary and the Ten Commandments. A second edition, Alphabetum Barmanorum, was revised by Father Gaetano M. Montegazza and published in 1787, with assistance from U Tsaw, a Burmese convert who contributed new styles of Burmese characters that were used for the recasting of the Burmese font.1

The evangelical revival of the Protestant church in the 18th century saw the arrival of Protestant missions in the East. One of the key figures of the movement was British missionary and Baptist minister William Carey, who set up the Serampore Mission in West Bengal, India, in 1800 with fellow missionaries Joshua Marshman and William Ward, who was also a printer. The mission’s press produced several works in Burmese type, notably Scottish linguist John Leyden’s A Comparative Vocabulary of the Barma, Maláyu and T’hái Languages (1810), which features both Burmese and Jawi scripts, and A Grammar of the Burman Language (1814) compiled by Felix Carey, the eldest son of William Carey.2

In 1807, the Serampore Mission extended its work to Burma, and Felix Carey was appointed one of its first missionaries. Carey was a trained doctor, and having apprenticed under William Ward, had become a proficient printer. The younger Carey was also particularly adept at languages and quickly attained fluency in Burmese and Pali. These skills put him in good stead when he oversaw the production of Burmese font types, which were used in the printing of his translation of the Gospel of Matthew.3 Progress was slow, however, as the Burmese station lacked a printing press and all the printing had to be done in Serampore.

To this end, Carey made an appeal to King Bodawpaya for permission to set up a Christian printing press in Burma. Having found favour with the Burmese court for his medical skills, and coupled with the king’s interest in having a press for government printing, the request was granted.

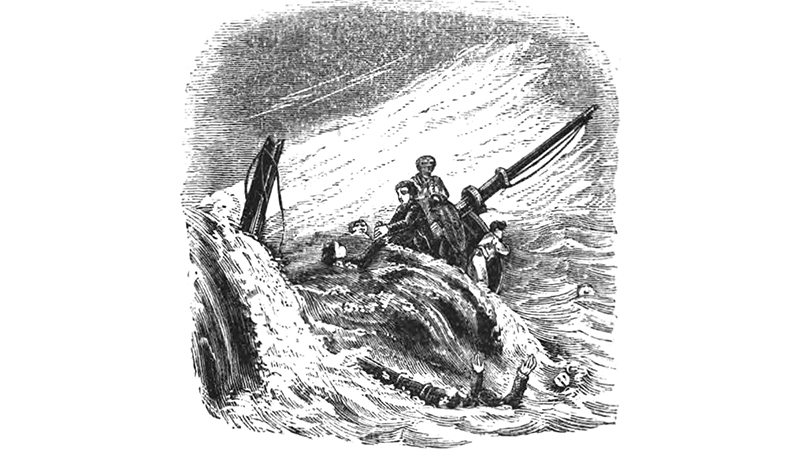

In August 1814, Carey and his family set sail with the printing press for the capital Ava, where he had been summoned into service by the Burmese court. Tragically, the boat capsized en route, drowning his wife and two young children. Although Carey survived, the Burmese types were lost in the watery depths of the Irrawaddy River.4

A wood engraving depicting the shipwreck of Felix Carey. He lost his wife and children when the boat that carried the first printing press in Myanmar capsized in the Irrawaddy River in August 1814. Image reproduced from Burns, J. (1854). Missionary Enterprises in Many Lands (p. 220). London: Knight & Son. Original Source The British Library, 1366.b.9.

A wood engraving depicting the shipwreck of Felix Carey. He lost his wife and children when the boat that carried the first printing press in Myanmar capsized in the Irrawaddy River in August 1814. Image reproduced from Burns, J. (1854). Missionary Enterprises in Many Lands (p. 220). London: Knight & Son. Original Source The British Library, 1366.b.9.

The British mission in Burma was brought to a standstill by this setback, and the work was turned over to Adoniram Judson, the first American Baptist missionary to Burma. He had arrived in Rangoon (now Yangon) in 1813 and spent the next 37 years of his life in Burma. Among his many achievements was the development of the American Mission Press in Rangoon, which produced some of the earliest printed works in Burma, both religious and secular. These include translations of the Bible, catechisms, religious tracts, dictionaries, school textbooks and the Maulmain Almanac and Directory.5

The American Baptist Mission on Merchant Street, Rangoon, in the early 20th century. Image reproduced from Wright, A., Cartwright, H.A., & Breakspear, O.T. (Eds.). (1910). Twentieth Century Impressions of Burma: Its History, People, Commerce, Industries, and Resources (p. 137). London; Durban; Perth (W.A.): Lloyd’s Greater Britain Pub. Co. Retrieved from Cornell Southeast Asia Visions website.

The American Baptist Mission on Merchant Street, Rangoon, in the early 20th century. Image reproduced from Wright, A., Cartwright, H.A., & Breakspear, O.T. (Eds.). (1910). Twentieth Century Impressions of Burma: Its History, People, Commerce, Industries, and Resources (p. 137). London; Durban; Perth (W.A.): Lloyd’s Greater Britain Pub. Co. Retrieved from Cornell Southeast Asia Visions website.

In 1816, Burma finally received its first operational printing press when fellow American George Henry Hough joined Judson in Burma, bringing with him a printing press and a font of Burmese type donated by the Serampore Mission. The press was used to print a tract, a catechism and a translation of the Gospel of Matthew completed by Judson. Although there are no known extant copies of the tract and catechism, a copy of Judson’s Gospel of Matthew (1817) can be found in The British Library, making it the oldest known surviving work printed in Burma. After these initial efforts, there appears to be very little printing done in the country as the printing press was relocated to India before the onset of the First Anglo-Burmese War (1824–26).6

Judson was able to revive printing activities in 1830 when Cephas Bennett, another American Baptist missionary who was also a printer, joined him in Moulmein (now Mawlamyine) bearing a press and types donated by the American Baptist church. In the early years, the American Baptist Mission Press was responsible for almost all the printing carried out in Burma, producing both Christian and secular works such as textbooks and language books, until the emergence of private presses in the mid-19th century.

The Burma Herald Press, which was the first commercial press to make Burmese works widely available to the reading public, began publishing general works, legal texts, moral tracts and popular Burmese plays (pya-zat) in 1868.

In 1886, Philip Ripley, who was born in Burma, started the Hanthawaddy Press in Rangoon which became a leading publishing house in Burma in the early 20th century, known in particular for its publication of Burmese classics and Buddhist texts such as the Tripitaka. In 1864, the first royal printing press in Mandalay was established by King Mindon.7

Thailand

In many ways, the development of printing in Thailand is similar to that of Myanmar. Catholic missionaries began settling in Thailand from the 16th century. Printing was later introduced by the Society of Foreign Missions of Paris (Société des Missions Étrangères de Paris), which had established a presence in Thailand from the 17th century. Most sources concur that Kham son Christang Phàc ton is the earliest known publication in the Thai language in the kingdom. This book of Christian teachings was printed in Romanised Thai in 1796 by Father Arnaud Garnault of the Church of Santa Cruz in Thonburi (an area in modern Bangkok).

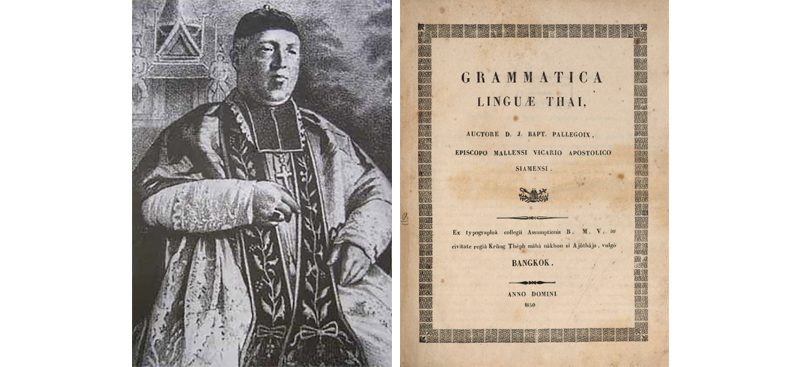

Another prominent figure in Catholic printing was Father Jean-Baptiste Pallegoix who arrived in Thailand in 1830. In 1838, Father Pallegoix secured his first press which he used to print a primer in Romanised Thai. A second press, made of iron, was received in 1841. With these, Father Pallegoix printed works in Thai, Annamese, Cochinese and Malay, but all in Roman script. Most of the materials he produced were school textbooks and religious literature. One of his most notable publications is Grammatica Linguae Thai (1850), a Thai grammar written in Latin with text in Thai script produced from type acquired from American Protestant missionaries. Pallegoix also published Dictionarium Latinum Thai (1850), a Latin-Thai dictionary, in the same year.8

(Left) An undated portrait of Father Jean-Baptiste Pallegoix. He was the Vicar Apostolic of Eastern Siam and one of the earliest printers in Thailand. One of his most notable publications is Grammatica Linguae Thai (1850), a Thai grammar which contains both Latin and Thai script. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. (Right) The title page of Grammatica Linguae Thai (1850). It was published in Bangkok. Courtesy of Bayerische Staatsbibliothek München, 4 L.as. 271 h, title page, urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb10522371-0.

(Left) An undated portrait of Father Jean-Baptiste Pallegoix. He was the Vicar Apostolic of Eastern Siam and one of the earliest printers in Thailand. One of his most notable publications is Grammatica Linguae Thai (1850), a Thai grammar which contains both Latin and Thai script. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. (Right) The title page of Grammatica Linguae Thai (1850). It was published in Bangkok. Courtesy of Bayerische Staatsbibliothek München, 4 L.as. 271 h, title page, urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb10522371-0.

The oldest publication in Thai script was, however, produced outside of Thailand. A catechism by Ann Hasseltine Judson, the wife of Adoniram Judson, was printed in Serampore in 1819. Also printed in India, is the oldest known surviving publication with substantial Thai script. In 1828, A Grammar of the Thai, or Siamese Language written by James Low, a captain with the British East India Company, was published by the Baptist Mission Press in Calcutta (now Kolkata). The manuscript was first presented to the Asiatic Society of Calcutta in 1822 and later published on the urging of Robert Fullerton, then Governor of the Straits Settlements, in view of British commercial interests in Thailand. This early work, which featured Thai script printed from type and lithography was, unfortunately, riddled with typographical errors that revealed Low’s inadequate grasp of the language and the challenges of vernacular printing.9

Interestingly, some of the earliest printing in the Thai script took place in Singapore. The first Siamese type and printing press in Thailand were also acquired from Singapore. The oldest record of Thai printing in Singapore dates back to 1822 when Samuel Milton, an agent of the London Missionary Society stationed in Singapore, wrote to the London headquarters to inform them that three men were cutting Siamese type for the printing of a Christian tract. The following year, Milton reported that he had purchased a font of Siamese type from Calcutta and that a Siamese translation of the Book of Genesis – the first book in the Christian Bible – was already in the press.10

In the early 19th century, the presses of the London Missionary Society and the American Board of Commissioners of Foreign Missions (ABCFM) based in Singapore were responsible for printing hundreds of Siamese tracts distributed in the kingdom.11 A rare example of one of these tracts survives in the collection of The British Library. The pamphlet carries an inscription that reads “Tract of Sermon on the Mount in Siamese by J.T. Jones. Printed at Singapore, 1835”. This is very likely the work of John Taylor Jones of the American Baptist Mission, one of the earliest Protestant missionaries to Thailand.12

An undated portrait of the American missionary John Taylor Jones, one of the earliest Protestant missionaries to Thailand. Image reproduced from The Missionary Magazine, Vol. XXXIV, No. 1, January 1853. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons.

An undated portrait of the American missionary John Taylor Jones, one of the earliest Protestant missionaries to Thailand. Image reproduced from The Missionary Magazine, Vol. XXXIV, No. 1, January 1853. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons.

In 1835, Jones visited Singapore to publish his first translation of the Gospel of Matthew into the Thai language. The printing was completed using ABCFM’s font of Siamese metallic type that had been cast from the matrices made under the supervision of the Serampore Mission Press. This type and a wooden press were subsequently brought to Bangkok from Singapore by American missionary Dan Beach Bradley in 1835. Many regard this as Thailand’s first Siamese type and printing press.13 Bradley also later developed a Thai typeface that became widely used, and oversaw the production of many of Thailand’s early printed works.14

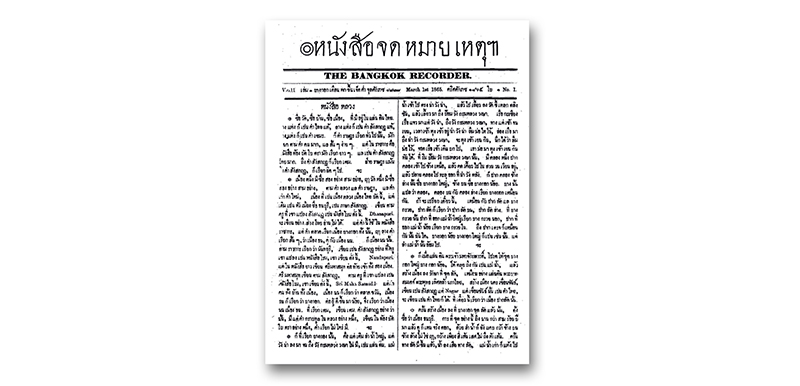

The ABCFM and the American Baptist Mission were running presses in Thailand by 1836.15 One of the earliest surviving examples from this period is a Christian tract, Ruang Phrasasana, published in 1837.16 Besides Christian literature, the ABCFM press under the direction of Bradley also published secular works such as the first Thai newspaper, The Bangkok Recorder (1844–45), the Bangkok Calendar, and A Journal of the Tour of the Siamese Embassy to & from London in the Year of our Lord 1857 & 1858 (1861) by Mom Rajodai.

The front page of The Bangkok Recorder (1 March 1865), the first Thai newspaper. It was published by American missionary Dan Beach Bradley. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons.

The front page of The Bangkok Recorder (1 March 1865), the first Thai newspaper. It was published by American missionary Dan Beach Bradley. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons.

By the late 19th century, there were several commercial printing houses operating in Bangkok. In 1865, missionary Samuel Smith established Bang Kho Laem Publishing House, which initially produced Christian literature and Buddhist sermons but later became a profitable business in publishing classical Thai epic poems such as Khun Chang Khun Phaen and Phra Aphai Mani.17

In addition to missionary and commercial presses, the Thai monarchy and Buddhist temples were also involved in various forms of publishing. The first printed government document in Thailand, issued in 1839, was a royal proclamation on the ban of the opium trade. Prince Mongkut (later King Rama IV) became the first Thai to set up a press while he was an abbot at the Wat Pavaranivesa monastery. He formally established the official government press in 1858 when he became king.

The government press took charge of publishing the Ratchakitchanubeksa (Royal Gazette), administrative papers and records (chomaihet), handbooks, laws and speeches. Various members of the royal household continued to play active roles in publishing Thai literature right up to the early 20th century.18

Mention should also be made of the important role that Buddhist monasteries performed in the publication of cremation volumes to honour those who had died. Distributed to guests during funerals, these books contain information and details on the lives of the deceased.19

In examining how printing technology spread to mainland Southeast Asia, we can see the role of the colonial government (in French Indochina) and Christian missionaries (in Myanmar and Thailand) in bringing and applying the know-how to the region. However, it is equally clear that the local inhabitants of mainland Southeast Asia – whether they were kings, Buddhist clergy or the intelligentsia – saw the potential of the printing press to quickly disseminate information and ideas. Local presses were thus established to serve the people’s needs.

Gracie Lee is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She works with the rare materials collections, and her research areas include Singapore’s publishing history and the Japanese Occupation.

Gracie Lee is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She works with the rare materials collections, and her research areas include Singapore’s publishing history and the Japanese Occupation.

Related articles

*For the first essay titled Early Printing in Indochina, see:

Lee, G. (2020, Jan–Mar). Early printing in Indochina. BiblioAsia, 15 (4), 50–53.

For other related essays on printing, see:

Lee, M. (2020, Jan–Mar). From Lat Pau to Zaobao: A history of Chinese newspapers. BiblioAsia, 15 (4), 44–49.

Mazelan Anuar. (2017, Oct–Dec). Early Malay printing in Singapore. BiblioAsia, 13 (3). 40–43.

Tan, B. (2016, Jan–Mar). A magazine for the Straits Chinese. BiblioAsia, 11 (4), 80–81.

Tan, B. (2017, Jan–Mar). Claudius Henry Thomsen: A pioneer in Malay printing. BiblioAsia, 12 (4), 26–31.

NOTES

-

Herbert, P., & Milner, A. (Eds.). (1989). South-East Asia: Languages and literature: A select guide (p. 9). Arran, Scotland: Kiscadale Publications. (Call no.: RSING 495 SOU); San, S.M. (2010, December). Early printing in Burma. Southeast Asia Library Group Newsletter, 42, 32–33. Retrieved from Southeast Asia Library Group website; Pearn, B.R. (1960). Burmese printed books before Judson (pp. 475–476). Fiftieth Anniversary Publications, No. 2. Rangoon: Burma Research Society. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.1 BUR-[GBH]); Bigandet, P.A. (1996; orig. 1887). An outline of the history of the Catholic Burmese mission from the year 1720 to 1887 (pp. 12–23). Bangkok, Thailand: White Orchid Press. (Call no.: RSEA 266.2591 BIG); National Library of Australia. (n.d.) Alphabetum barmanum, seu, bomanum: Regni avae finitimarum regionum. Retrieved from National Library of Australia website; Thae, T.H. (2011, January 3). Barnabite legacy a treasure for collectors. Retrieved from Myanmar Times website. ↩

-

Herbert & Milner, 1989, p. 9; San, Dec 2010, pp. 33–34; Pearn, 1960, pp. 475–476. ↩

-

Wylie, M. (1854). Bengal as a field of missions (pp. 52–59). London: W.H. Dalton. Retrieved from Internet Archive website; Baptist General Convention. (1841). Baptist Missionary Magazine, 21, p. 211. Retrieved from HathiTrust website. ↩

-

Marshman, J.C. (1864). The story of Carey, Marshman & Ward: The Serampore missionaries (pp. 198–199). London: A. Strahan & Co.. Retrieved from HathiTrust website; Baptist Missionary Society. (1815). The Baptist Magazine for 1815, 7, pp. 207, 519. Retrieved from HathiTrust website. ↩

-

Rhodes, D.E. (1969). India, Pakistan, Ceylon, Burma and Thailand (pp. 81–86). Amsterdam: [A. L.] van Gendt; New York: Schram. (Call no.: RSEA 686.2095 RHO) ↩

-

Herbert & Milner, 1989, p. 9; Rhodes, 1969, p. 82; San, Dec 2010, p. 34. ↩

-

Herbert & Milner, 1989, p. 10; Rhodes, 1969, pp. 83–86; San, Dec 2010, p. 34; Suarez, M.F., & Woudhuysen, H.R. (Eds.). (2013). The book: A global history (p. 633). Oxford: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: 002.09 BOO); Wright, A., Cartwright, H.A., & Breakspear, O.T. (Eds.). (1910). Twentieth century impressions of Burma: Its history, people, commerce, industries, and resources (pp. 132–139). London; Durban; Perth (W.A.): Lloyd’s Greater Britain Pub. Co. Retrieved from Cornell University Library website. ↩

-

Winship, M. (1986). Early Thai printing: The beginning to 1851. Crossroads: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 3 (1), 45–47. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website; Bressan, L. (2003). The first printed sentence in Thai: A.D. 1646. Journal of the Siam Society, 91, p. 241. Retrieved from Siam Society website; Kantaphong, C. (2017). Khâm Són Christang: A witness of the French missionnaries’ knowledge of Thai language during the Ayutthaya era of Siam (Thailand). Proceedings, pp. 184–186. Retrieved from the 13th International Conference on Thai Studies website; Smyth, D. (2001). Farangs and Siamese: A brief history of learning Thai (p. 279). In K. Tingsabadh & A. Abramson. (Eds.), Essays in Tai linguistics. Bangkok: Chulalongkorn University Press. Retrieved from SEAlang website; Herbert & Milner, 1989, p. 30. ↩

-

Herbert & Milner, 1989, p. 30; Winship, 1986, pp. 48–49; Smyth, D. (2007). James Low, on Siamese Literature (1839). Journal of the Siam Society, 95, pp. 159–160. Retrieved from The Siam Society website; Low, J. (1828). A grammar of the T,hai or Siamese language. Calcutta: Baptist Mission Press. Retrieved from HathiTrust website; Nida, E.A. (Ed.). (1972). The book of a thousand tongues (Rev. ed., p. 427). London: United Bible Societie. Retrieved from Internet Archive website. ↩

-

Byrd, C.K. (1970). Early printing in the Straits Settlements, 1806–1858 (pp. 13–16). Singapore: National Library. (Call no.: RSING 686.2095957 BYR); Su, C. (1996). The printing presses of the London Missionary Society among the Chinese (pp. 154–163) [Unpublished dissertation]. Retrieved from University College of London website; Church Missionary Society. (1825, January). The Missionary Register, 13, p. 46. London: L.B. Seeley & Son. Retrieved from HathiTrust website. ↩

-

Byrd, 1970, pp. 13–16; Su, 1996, pp. 154–163; Baptist General Convention. (June, 1840). The Baptist Missionary Magazine, 20, p. 144. Retrieved from HathiTrust website. ↩

-

Igunma, J. (2014, June 2). The beginnings of Thai book production: Thai books at the British Library. Retrieved from The British Library website; The British Library. (n.d.). Catalogue of [Tract and sermon on the Mount (in Thai). Singapore: s.n., 1835]. Retrieved from The British Library catalogue; The British Library. (n.d.). Catalogue of [The Gospel by Matthew in Thai. Singapore: s.n., 1835]. Retrieved from The British Library catalogue; Columbia University Libraries. (n.d.) Catalogue record of [St. Matthew’s gospel in Siamese / tr. by J. Taylor Jones and Charles Robinson]. [Singapore: s.n., 1835]. Retrieved from Columbia University Libraries website; Nida, 1972, p. 427. ↩

-

Winship. 1986, pp. 49–51; Bradley, D.C. (1861). Bangkok calendar for the year of our Lord 1861 (p. 82). Bangkok: American Missionary Association. Retrieved from HathiTrust website; Bradley, D.C. (1869). Bangkok calendar for the year of our Lord 1869 (p. 65). Bangkok: American Missionary Association. Retrieved from Google Books website; American Tract Society. (1836). Eleventh annual report of the American Tract Society (p. 89). New York: Society’s House. Retrieved from HathiTrust website. ↩

-

Mattani, M.R. (1988). Modern Thai literature: The process of modernization and the transformation of values (pp. 7–9). Bangkok: Thammasat University. (Call no.: RDET 895.91308 MAT); Winship, 1986, pp. 51–54. ↩

-

Winship, 1986, p. 51. ↩

-

Ginsburg, H. (2000). Thai art and culture: Historic manuscripts from Western collections (p. 40). London: The British Library. (Call no.: RART 745.6709593 GIN) ↩

-

Herbert & Milner, 1989, pp. 30–31; Wibha, S.K. (1975). The genesis of the novel in Thailand (pp. 23–25). Bangkok: Thai Watana Panich Co. (Call no.: RDET 895.913009 WIB); Mattani, 1988, pp. 8–10. ↩

-

Herbert & Milner, 1989, pp. 30–31;Winship, 1986, p. 51; Wibha, 1975, pp. 27, 31; Sulak, S. (1990). Siam in crisis: A collection of articles (pp. 134–157). Bangkok: Thai Inter-Religious Commission for Development. (Call no.: RSEA 306.09593 SUL); Suarez & Woudhuysen, 2013, p. 633. ↩

-

Herbert & Milner, 1989, p. 31; Igunma, 2 Jun 2014; National Library of Australia. (n.d.) Thai cremation volumes. Retrieved from National Library of Australia website; Svasti, P. (2014, October 27). Cremation books bring history to life. Retrieved from Bangkok Post website. ↩