Stamford Raffles and the Two French Naturalists

Danièle Weiler uncovers the work of two young French naturalists – Alfred Duvaucel and Pierre Médard Diard – who worked with Stamford Raffles between 1818 and 1820.

The lesser adjutant stork, or Leptoptilos javanicus (Horsfield, 1821), is a large wading bird found in wetland habitats in India and Southeast Asia. Image reproduced from Figures peintes d’oiseaux [et de reptiles], envoyées de l’Inde par Duvaucel et Diard (Painted depictions of birds [and reptiles], sent from India by Duvaucel and Diard). Courtesy of the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris. Digitised and available on National Library’s BookSG portal from August 2020.

The lesser adjutant stork, or Leptoptilos javanicus (Horsfield, 1821), is a large wading bird found in wetland habitats in India and Southeast Asia. Image reproduced from Figures peintes d’oiseaux [et de reptiles], envoyées de l’Inde par Duvaucel et Diard (Painted depictions of birds [and reptiles], sent from India by Duvaucel and Diard). Courtesy of the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris. Digitised and available on National Library’s BookSG portal from August 2020.

Stamford Raffles is probably best known as the East India Company (EIC) official who set up a trading post in Singapore that became part of the British Empire. However, a lesser-known fact about Raffles is that he was fascinated by the natural world. As a colonial administrator in Southeast Asia, he hired zoologists, botanists and naturalists to collect specimens and conduct research on his behalf.

Among the people Raffles hired were two young French naturalists – Alfred Duvaucel and Pierre Médard Diard. Interestingly, they were also on board the Indiana in January 1819 when Raffles and William Farquhar made landfall in Singapore and met Temenggung Abdul Rahman. Raffles went on to sign an interim agreement with the Temenggung before inking a treaty with Sultan Husain Shah and the Temenggung on 6 February, allowing the EIC to set up a trading post on the island.

As the two men were with Raffles at the time, they offer a unique account of the meeting between Raffles and the Malay court officials in Singapore:

“On reaching the harbour, the governor received the visit of three of the king’s aides-de-camp. These officers were not like our young men – tight-lipped, musk-scented and richly dressed – their black heads were shaven and covered with a dark-coloured turban; a large waistcoat hid their oiled, burnt, peeling and stooped backs. On their left side they carried a large kris or dagger and were bare-legged. These three Malays seemed delighted to see us, as if we had come for their benefit. The English were trying to find out what advantage might be gained by taking possession of their island; we, who were less concerned about this, questioned them about the animals that lived there. Who do you think these poor people listened to most willingly? They respond eagerly to the demands of their allies, and shrugged their shoulders listening to ours.”1

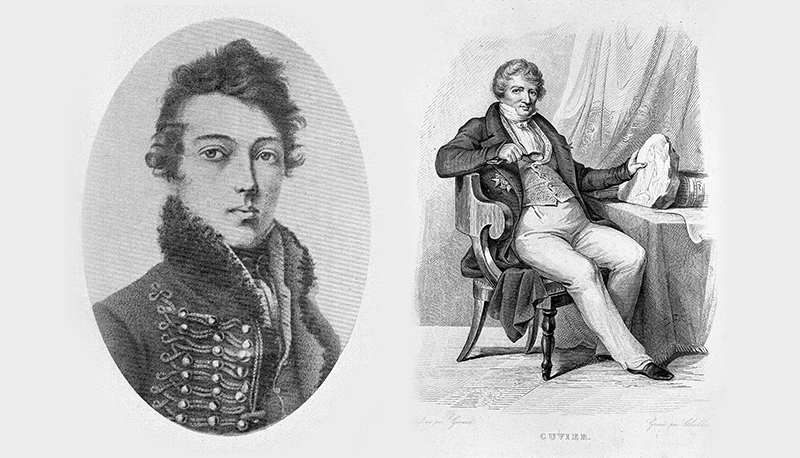

(Left) Pierre Médard Diard in the uniform of the Garde d’Honneur, which would date this portrait to between 1813 and 1814. He was around 19 years old at the time. Note: no image of Alfred Duvaucel appears to exist. Image reproduced from Peysonnaux, J.H. (1935). Vie voyages et travaux de Pierre Médard Diard. Naturaliste Français aux Indes Orientales (1794–1863). Voyage dans l’Indochine (1821–1824) (plate 2). Bulletin des amis du vieux Hué. (Right) The great French anatomist and zoologist George Cuvier, also known as Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, Baron Cuvier (1769–1832). Line engraving by A.J. Chollet after Lizinka de Mirbel and Giraud. Cuvier was also the stepfather of Alfred Duvaucel. Image from Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

(Left) Pierre Médard Diard in the uniform of the Garde d’Honneur, which would date this portrait to between 1813 and 1814. He was around 19 years old at the time. Note: no image of Alfred Duvaucel appears to exist. Image reproduced from Peysonnaux, J.H. (1935). Vie voyages et travaux de Pierre Médard Diard. Naturaliste Français aux Indes Orientales (1794–1863). Voyage dans l’Indochine (1821–1824) (plate 2). Bulletin des amis du vieux Hué. (Right) The great French anatomist and zoologist George Cuvier, also known as Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, Baron Cuvier (1769–1832). Line engraving by A.J. Chollet after Lizinka de Mirbel and Giraud. Cuvier was also the stepfather of Alfred Duvaucel. Image from Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

Diard and Duvaucel would have better luck later on, amassing a large collection of specimens, both while travelling with Raffles, as well as around Bencoolen (now Bengkulu) where Raffles was the Lieutenant-Governor at the time.

Unfortunately for the duo, their association with Raffles only lasted until March 1820 when their services were terminated. To make things worse, there was a dispute over how the collection would be divided and the two Frenchmen ended up losing a significant part of it. Undaunted, and perhaps not entirely legally, they managed to retrieve more specimens than they were entitled to before parting company with Raffles.

Diard and Duvaucel

Born in Paris in 1793, Alfred Duvaucel was the stepson of Georges Cuvier,2 a naturalist and zoologist sometimes known as the founding father of palaeontology. After a brief stint in the army, Duvaucel decided to become a naturalist and in December 1817, he sailed to India, bearing the title of Naturalist to King Louis XVIII of France. He arrived in Calcutta (now Kolkata) at the end of May 1818.

In Calcutta, Duvaucel met up with his friend Diard, who had arrived in the city a few months before. Diard, a year younger than Duvaucel, was interested in science and had studied medicine. In France, Diard had became acquainted with both Cuvier and his stepson Duvaucel. Diard had always been fascinated by the Far East and in 1817, he seized the opportunity to travel to India to settle inheritance matters on behalf of a family. He left Bordeaux on 20 August and arrived in Calcutta on 5 January 1818.

Both men got along well. In a letter to his mother, Duvaucel wrote: “(O)f all the pleasures I have experienced here, the most pleasant is to have met poor old Diard, whom I have embraced as a brother, and who is as constantly by my side as my own shadow, and with whom I am determined to live and work for two or three years.”3

The pair, who were in their mid-20s, soon left Calcutta for the French trading post of Chandernagor (now Chandannagar), about 50 km north. There, they began collecting animals to be stuffed or drawn. They frequently sent animal skeletons, drawings and mineralogical specimens back to the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle (National Musuem of Natural History) in Paris where Cuvier, Duvaucel’s stepfather, was assistant professor to the Chair of Animal Anatomy.

Diard and Duvaucel came to Raffles’ notice when he visited Calcutta – the EIC’s Asian headquarters – in late 1818. Raffles persuaded the two Frenchmen to collect specimens for him at his base in Bencoolen.4 In turn, the EIC would pay them an allowance to help defray expenses. Raffles also agreed that the collections and findings of the research would be shared equally among the three of them.5

Although there was no written agreement, Diard and Duvaucel accepted Raffles’ offer. They were short of funds and realised that they would not be able to continue working on their own for much longer. They trusted Raffles, who appeared to benefit from unlimited funds from the EIC. The only condition stipulated by the two Frenchmen, which Raffles agreed to, was that they could freely dispose of duplicate specimens and publish their observations in Calcutta, France or England as they chose.

To Penang, Singapore and Melaka

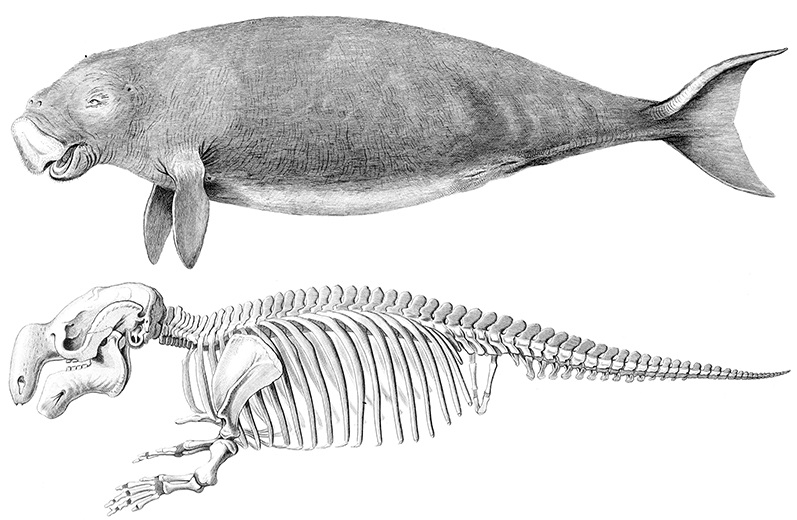

Accompanied by Diard and Duvaucel, Raffles and his entourage left Calcutta for Penang on 7 December 1818. The journey began well and even before reaching Penang, Diard and Duvaucel managed to capture a dugong, which they sketched, dissected and described. (Their notes and drawings were later published in 1824.6)

Dugong specimens obtained by Pierre Médard Diard and Alfred Duvaucel were sent by Stamford Raffles to British surgeon Everard Home in London. Based on the specimens, Home published two papers in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, which included these drawings. (Top) Image reproduced from Home, E. (1820, January 1). XX: Particulars respecting the anatomy of the dugong, intended as a supplement to Sir T.S. Raffles’ account of that animal. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, vol. 110, pp. 315–323. (Bottom) Image reproduced from Home, E. (1821, January 1). XVII: An account of the skeletons of the dugong, two-horned rhinoceros, and tapir of Sumatra, sent to England by Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, Governor of Bencoolen. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, vol. 111, pp. 268–275. Retrieved from The Royal Society Publishing website.

Dugong specimens obtained by Pierre Médard Diard and Alfred Duvaucel were sent by Stamford Raffles to British surgeon Everard Home in London. Based on the specimens, Home published two papers in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, which included these drawings. (Top) Image reproduced from Home, E. (1820, January 1). XX: Particulars respecting the anatomy of the dugong, intended as a supplement to Sir T.S. Raffles’ account of that animal. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, vol. 110, pp. 315–323. (Bottom) Image reproduced from Home, E. (1821, January 1). XVII: An account of the skeletons of the dugong, two-horned rhinoceros, and tapir of Sumatra, sent to England by Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, Governor of Bencoolen. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, vol. 111, pp. 268–275. Retrieved from The Royal Society Publishing website.

The group eventually arrived in Penang on 29 December 1818,7 and Diard and Duvaucel spent a few days on the island where they collected, among other animals, two species of fish and some rare birds.

On 19 January 1819, Raffles sailed from Penang on the Indiana, accompanied by the schooner Enterprise. After failing to land in Carimon (the Karimun Islands), they headed for Singapore and anchored off St John’s Island in the morning of 28 January 1819. That afternoon, Raffles and his entourage landed at the mouth of the Singapore River where Raffles met Temenggung Abdul Rahman. And that is how the two French naturalists ended up witnessing the fateful meeting that would lead to a major shift in Singapore’s history.

After the treaty was signed on 6 February 1819, Raffles left Singapore with the two naturalists and some of his men, leaving William Farquhar behind to manage the new settlement as its Resident. For the next five months, Raffles turned his attention to other matters in the region before returning to Bencoolen. One of the tasks he had been assigned by the EIC in Calcutta was to resolve a dynastic dispute in Aceh.

Diard and Duvaucel accompanied Raffles to the northern tip of Sumatra where the naturalists attempted to collect specimens from the area. This, however, did not go so well as Duvaucel’s letter to the French Academy of Sciences, which Cuvier was a member of, reveals:

“We stayed more than a month in this frightful country, without being able to penetrate the interior, nor procure most of the objects we had expected to collect there. The bad reputation of these people is justified every day by their conduct towards the Europeans, and Mr. Diard, convinced that the savages are only bad when they are mistreated, almost fell victim to this sense of false security which I have been fighting against for a long time: surrounded by two hundred Malays, with three of our servants he was able, it is true, to escape without injury, but he lost the fruit of his hunt, his weapons, and our luggage… Our stay at Achem, Padie, Tulosimawe has not greatly enriched our collections; a few plants, a few insects, a few birds, two or three snakes, four or five fish, and two deer are the only results of this arduous journey.”8

Diard and Duvaucel did manage to visit Melaka, then under the Dutch, where they had better luck than they did in Aceh. In his correspondence with the French Academy of Sciences, again Duvaucel wrote:

“No sooner had we arrived in Melaka than the whole city was at our door: all we have ever traded in here is opium and pepper and they could not guess what we wanted to do with the monkeys and birds we buy; in two hours we were able to acquire a bear, an Argus Pheasant and some other birds. The Dutch Governor has a young Orang-utang, and I shall leave you now to pay him a not disinterested visit.”9

While Diard and Duvaucel were arguably the first European naturalists to visit Singapore, the island does not appear to figure highly as a location for collecting specimens. Singapore, however, is mentioned as a place where they captured and named the common treeshrew. In a paper published in 1822, they described the squirrel-like mammal as follows:

“During our stay in Pulo Penang and Singapore, on several occasions we killed a small quadruped in the woods which we took at first for a Squirrel but our examination of it soon led us to recognise that it belonged to the Insectivora family… it perfectly resembled a species of small squirrel that we meet at every step of the way in the woods of Singapore… we gave it the name Sorex Glis, which gives at one and the same time an idea of its outer appearance and true nature.”10

Pierre Médard Diard and Alfred Duvaucel discussed catching the common treeshrew (Sorex glis) in Singapore and Penang in an article titled “Notice – Sur une nouvelle espèce de Sorex – Sorex Glis” published in Asiatick Researches (Volume XIV, 1822). Although the species was given its first scientific name by Diard in 1820, it was subsequently renamed as Tupaia glis. Image reproduced from Pechuel-Loesch, E. (1890) Brehms Tierleben. Allgemeine Kunde des Tierreichs. Dritte, gänzlich neubearbeitete Auflage. Säugetiere – Zweiter Band. Leipzig: Bibliographisches Institut,. Retrieved from Biodiversity Heritage Library website.

Pierre Médard Diard and Alfred Duvaucel discussed catching the common treeshrew (Sorex glis) in Singapore and Penang in an article titled “Notice – Sur une nouvelle espèce de Sorex – Sorex Glis” published in Asiatick Researches (Volume XIV, 1822). Although the species was given its first scientific name by Diard in 1820, it was subsequently renamed as Tupaia glis. Image reproduced from Pechuel-Loesch, E. (1890) Brehms Tierleben. Allgemeine Kunde des Tierreichs. Dritte, gänzlich neubearbeitete Auflage. Säugetiere – Zweiter Band. Leipzig: Bibliographisches Institut,. Retrieved from Biodiversity Heritage Library website.

Eventually, Raffles completed the work he needed to do and on 28 June 1819, Diard and Duvaucel sailed with Raffles from Singapore for west Sumatra, arriving in Bencoolen about a month later. During the six months that they were with Raffles, their difficulties in Aceh notwithstanding, they had managed to amass a large collection of animals that filled half the ship.

The Fallout with Raffles

In Bencoolen, Diard and Duvaucel settled in Raffles’ country house and began their work hunting and collecting animals to study. However, this happy state was not to last as Raffles informed them that the EIC was going to stop paying them.

This was actually the second major blow that Raffles delivered to the two naturalists. The first was when Raffles reneged on his verbal agreement made in December 1818 that the collection and the research findings would be equally shared among the three of them. On 7 March 1819, Raffles wrote to the Frenchmen, informing them that they would not actually own anything they had collected. His letter read:

“Your researches to be confined to Sumatra and the smaller Islands in its immediate vicinity. The draftsmen, &c. engaged by you to be entertained at the charge of Government, who will also defray all incidental and necessary expenses to which you may be subjected in the prosecution of your researches, on condition that such researches are made for and on account of the Honourable The East India Company, and that your collections &c. are considered as their property. An estimate to be framed of your monthly expenses for such establishment, &c. in which a fixed sum will be paid to you to cover all charges of every description… With reference to your present establishment, and the expenses you must necessarily be subjected to, a fixed monthly allowance of five hundred ducats is considered adequate to cover all your disbursements…”11

Losing the financial support of the EIC would be disastrous for them. In an effort to salvage the situation, Diard and Duvaucel exchanged a number of letters with Raffles in March 1820 attempting to present alternative proposals, but it was in vain. In a letter dated 15 March 1820, Raffles announced that he would terminate their services. That same day, he appointed a committee to seize the entire collection of objects, along with the descriptions, observations and drawings, from the two naturalists.

Raffles ordered that one of each item was to be sent to him, with the duplicate placed on the Mary to be shipped back to Europe and any surplus stored at Government House in Bencoolen. The committee was also instructed to compile a catalogue of all items. At the same time, Raffles informed Diard and Duvaucel of the new arrangement and requested that they provide assistance to the committee.12

In a subsequent about-turn, Raffles agreed that Diard and Duvaucel could keep some specimens provided there were spares available. This was on condition that the specimens taken did not arrive in France before those sent to England were received and noticed.13

Diard and Duvaucel felt that this was still not good enough. On account of their good relations with the English in Bencoolen, the two naturalists managed to secretly obtain additional specimens which they hid in their luggage, replacing the contents of some crates with rags.14 The specimens arrived safely in France and were received by the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, some of which are on display at the institution today.

Around the same time that Raffles sent the collection to England on board the Mary, he also compiled a Descriptive Catalogue, which was published in volume XIII of The Transactions of the Linnean Society of London (1821–23).15 This established Raffles’ reputation as a zoologist when in fact the Descriptive Catalogue was mainly the work of his secretary, William Jack.16

Interestingly, in the introduction to this catalogue, Raffles briefly explains the situation that arose between him and Diard and Duvaucel. He wrote:

“They advanced pretensions diametrically opposed to the spirit and letter of their engagement and altogether inconsistent with what I had a right to expect from them, or they from me. Thus situated, I had no alternative but to undertake an immediate description of the collection myself, or to allow the result of all my endeavours and exertions to be carried to a foreign country.”17

That said, Raffles did have kind words for the pair: “They are young men not deficient in zeal, and though misled for the moment by private and national views, will, I doubt not, profit by the means I have afforded them, and eventually contribute to our further knowledge of the zoology of these islands.”18

An Amicable Parting

Once the collections had been sent to England and France, Diard and Duvaucel asked Raffles if they could sail to Batavia (now Jakarta) on the Indiana. Raffles agreed on condition that they provide the aforementioned committee with all the remaining specimens, drawings and descriptions still in their possession.19

Before Diard and Duvaucel left Bencoolen, Raffles penned a final letter to the naturalists on 22 March 1820. He wrote:

“No man can appreciate more highly than myself the zeal and personal exertion which you have displayed in making these collections and researches, I am sincerely desirous of securing to you the full measure of credit due to them, and I think you must be satisfied that it is always been my wish to contribute to the extension of science… I conclude with expressing my regret at the necessary close of our public relation, but at the same time my satisfaction at its being about to terminate in an amicable adjustment.”20

Diard and Duvaucel were equally effusive in their reply. They wrote in French:

“Although it has been painful for us to engage with you in a public dispute, we have been pleased to receive the recompense of receiving your assurance that this opposition on our part has not affected the esteem in which we hold you. We are eager therefore to express how grateful we are at this fresh proof of your benevolence.

“We are more than pleased, Sir, to see that you have been able to appreciate the motives for our conduct, so that henceforth we may have no other desire than to conform to the views you have expressed. We beg you therefore, to be persuaded that we gladly agree to your proposals and that nothing could be more satisfactory to us before we leave Bencoolen than to prove to you our perfect confidence in your amicable intentions.”21

After bidding Raffles farewell, the two naturalists wanted to make good their losses and immediately set to work again. The pair agreed to go their separate ways this time but to meet up at some point in future. Unfortunately, they never met again.

Duvaucel left on 1 April 1820 for Padang where he amassed 14 cases of stuffed animals and skeletons, including the skeleton and skin of a Sumatran tapir, the skeletons and skins of four rhinoceroses of two recognisably distinct species, a large number of monkeys (some still alive), reptiles and two kinds of deer.

In 1821, Duvaucel decided to turn his attention to collecting animals in South Asia. While in India, he became severely injured after being attacked by a rhinoceros while on a hunt. Although Duvaucel survived the initial attack, he died about a year later in 1824. Accounts at the time pointed to either fever or dysentery as the cause of his death.

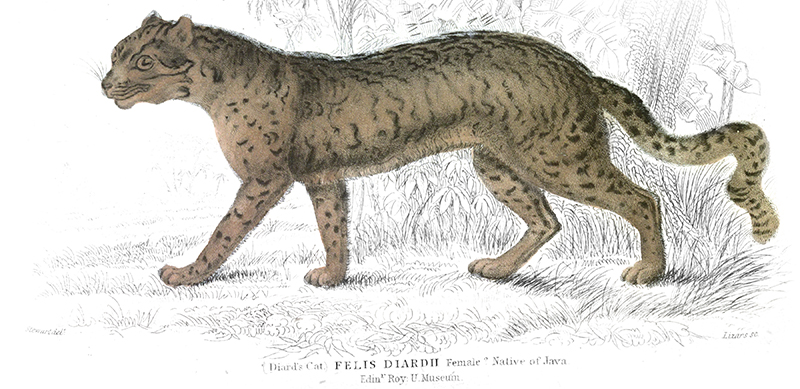

Georges Cuvier named a leopard, the Neofelis diardi, commonly known as the Sunda clouded leopard, after Pierre Médard Diard in 1823. The animal was only confirmed to be a distinct species in 2007. Image reproduced from Jardine, W. (1834). The Natural History of the Felinae (plate 22). Edinburgh: W.H. Lizars, and Stirling and Kenney. Retrieved from Internet Archive website.

Georges Cuvier named a leopard, the Neofelis diardi, commonly known as the Sunda clouded leopard, after Pierre Médard Diard in 1823. The animal was only confirmed to be a distinct species in 2007. Image reproduced from Jardine, W. (1834). The Natural History of the Felinae (plate 22). Edinburgh: W.H. Lizars, and Stirling and Kenney. Retrieved from Internet Archive website.

Diard, on the other hand, stayed on in the Dutch East Indies (modern-day Indonesia) and lived in the region until his death in 1863. In addition to collecting animals, Diard also worked for the Dutch colonial government. He died from arsenic poisoning caused by the chemical used in the preservation of animal skins when he was assembling a new collection for a museum in Leiden in the Netherlands.

Raffles’ view that the two men would “eventually contribute to our further knowledge of the zoology of these islands” turned out to be prescient. Diard and Duvaucel managed to send some 2,000 items, comprising stuffed animals, skins and skeletons from the region back to the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris. They also sent back numerous drawings of animals and plants that they had commissioned.

Their memory also lives on in a number of animals named after them. These include a species of deer, Cervus duvaucelii (first described by Georges Cuvier); a bird, the scarlet-rumped trogon Harpactes duvaucelii; a bat, Pachysoma duvaucelii; the Indian squid, Loligo duvaucelii; the Sunda clouded leopard, Neofelis diardi (also first described by Cuvier); a snake, Typhlops diardii; and Rattus diardii, a kind of rat.

Georges Cuvier named a species of deer, the Rucervus duvaucelii, commonly known as the barasingha, after Alfred Duvaucel in 1823. Image reproduced from Sclater, P. L. (1871). On certain species of deer now or lately living in the society’s menagerie. Transactions of the Zoological Society of London, 7 (5): 333–352. Retrieved from Biodiversity Heritage Library website.

Georges Cuvier named a species of deer, the Rucervus duvaucelii, commonly known as the barasingha, after Alfred Duvaucel in 1823. Image reproduced from Sclater, P. L. (1871). On certain species of deer now or lately living in the society’s menagerie. Transactions of the Zoological Society of London, 7 (5): 333–352. Retrieved from Biodiversity Heritage Library website.

|

| This essay is adapted from Danièle Weiler’s chapter on Diard and Duvaucel in Voyageurs, Explorateurs Et Scientifiques: The French and Natural History in Singapore (2019) published by the Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum. |

| The book can be reserved for on-site reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library, National Library Building, on the PublicationSG portal. |

| Close to 120 drawings of animals and plants commissioned by the two French naturalists have been compiled in Figures peintes d’oiseaux [et de reptiles], envoyées de l’Inde par Duvaucel et Diard (Painted depictions of birds [and reptiles], sent from India by Duvaucel and Diard). The digitised drawings were provided by the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris and will be available on the National Library’s BookSG portal in August 2020. |

Danièle Weiler contributed a chapter to the book, Voyageurs, Explorateurs Et Scientifiques: The French and Natural History in Singapore (2019). She is also the co-author of The French in Singapore: An Illustrated History, 1819–Today (2011). A retired teacher and librarian now back in France, she lived in Singapore for 15 years where she worked at the Lycee Francais de Singapour.

Danièle Weiler contributed a chapter to the book, Voyageurs, Explorateurs Et Scientifiques: The French and Natural History in Singapore (2019). She is also the co-author of The French in Singapore: An Illustrated History, 1819–Today (2011). A retired teacher and librarian now back in France, she lived in Singapore for 15 years where she worked at the Lycee Francais de Singapour.

NOTES

-

Notice sur les voyages de MM. Diard et Duvaucel, naturalistes français, dans les Indes orientales et dans les iles de la Sonde, extraite de leur correspondance et lue à l’Académie des sciences le 14 mai 1821 par M. le baron George Cuvier, membre de l’institut. Revue Encyclopédique, ou analyse raisonnée des productions les plus remarquables dans la littérature, les sciences et les arts, par une réunion de Membres de l’Institut et d’autres hommes de lettres. Tome X. Paris, Avril 1821 (p .478); Société Asiatique. (1824, Mars–Avril). Notice sur le voyage de M. Duvaucel. Journal Asiatique, IV, pp. 137–145. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, Buron Cuvier (1769–1832) was a major figure in natural sciences research in the early 19th century. He established the sciences of palaeontology and comparative anatomy. See Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2020, May 9). Georges Cuvier. Retrieved from Britannica website. ↩

-

Coulmann, J.-J. (1973) Réminiscences (Tome 1, p. 146). Genève Slatkine Reprints. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Bastin, J.S. (2014). Raffles and Hastings: Private exchanges behind the founding of Singapore (p. 195). Singapore: National Library Board and Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Call no.: RSING 959.5703 BAS-[HIS]) ↩

-

Cuvier, 14 May 1821, p. 478. ↩

-

Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, E., & Cuvier, F. (1824). Histoire naturelle des mammifères: Avec des figures originales, coloriees, dessinees d’apres des animaux vivans. A Paris: Chez A. Belin. Retrieved from Biodiversity Heritage Library website. ↩

-

Cuvier, 14 May 1821, p. 478. ↩

-

Cuvier, 14 May 1821, p. 479. ↩

-

Diard, P.M., & Duvaucel, A. (1822). On the Sorex Glis. Asiatick Researches or Transactions of the Society, Instituted in Bengal for Inquiring into the History and Antiquities, the Arts, Sciences and Literature of Asia, vol. XIV, pp. 471–475. Retrieved from Biodiversity Heritage Library website. ↩

-

Raffles, S. (1830). Memoir of the life and public services of Sir Stamford Raffles: Particularly in the government of Java 1811–1816, and of Bencoolen and its dependencies, 1817–1824: With details of the commerce and resource of the eastern archipelago, and selections from his correspondence (p. 703). London: J. Murray. Retrieved from BookSG. ↩

-

Peysonnaux, J.H. (1935). Vie voyages et travaux de Pierre Médard Diard. Naturaliste Français aux Indes Orientales (1794–1863). Voyage dans l’Indochine (1821–1824) (p. 21). Bulletin des amis du vieux Hué. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Raffles, T.S. (1821–1823). Descriptive catalogue of a zoological collection, made on account of the honorable East India Company, in the island of Sumatra and its vicinity, under the direction of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, Lieutenant-Governor of Fort Marlborough, with additional notices illustrative of the natural history of those countries. The Transactions of the Linnean Society of London, volume XIII, pp. 239–74, 277–340. Retrieved from Biodiversity Heritage Library website. ↩

-

Raffles, 1821–1823, p. 240. ↩

-

Raffles, 1821–1823, p. 240. ↩