Cloudy With A Slight Chance of Rain:

Singapore's Meteorological Service

The Met Service was officially set up in 1929, but people have been recording weather data here for the last 200 years. Lim Tin Seng has the details.

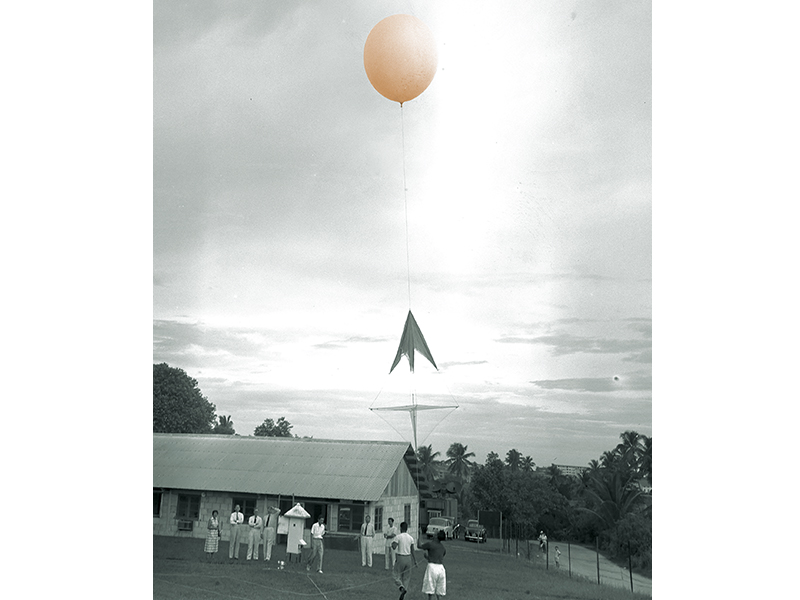

A pilot balloon at the Paya Lebar observation station, 1955. The balloon measures wind speed and direction in the upper atmosphere. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A pilot balloon at the Paya Lebar observation station, 1955. The balloon measures wind speed and direction in the upper atmosphere. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Low-lying countries like Singapore face an existential threat from climate change. By the year 2100, sea levels are projected to rise by at least one metre, which is a problem given that 30 percent of Singapore lies less than 5 metres above sea level.

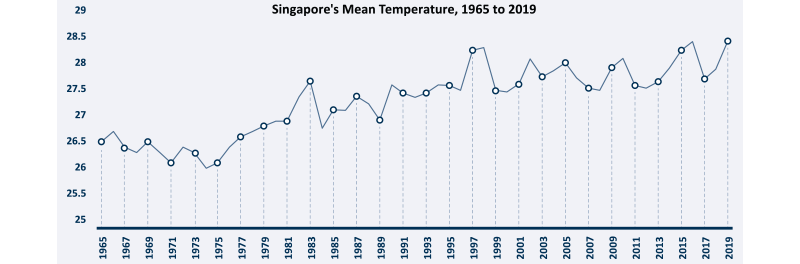

But there is no need to wait 80 years to see the impact of climate change on Singapore. Already, the average sea level around Singapore is now 14 cm higher than it was 50 years ago, according to the Meteorological Service Singapore (MSS).1 In 2019, the MSS reported that four of the island’s 10 warmest years on record have been in the last five years.

The temperature records of the MSS date back to 1929 while its rainfall readings began in 1869. But the systematic observation of Singapore’s weather stretches back even further. Throughout the 19th century, scientifically inclined individuals, armed with thermometers and rain gauges, have been earnestly documenting Singapore’s rainfall and temperature. They were a mixed bag of people that included government officials, a missionary and even a magistrate.

In 1869, the Medical Department of the Straits Settlements began collecting weather data seriously. Its efforts led to the formation of a dedicated government department for recording and analysing weather information in 1929 – the Malayan Meteorological Service, the predecessor of today’s MSS.

The Beginnings

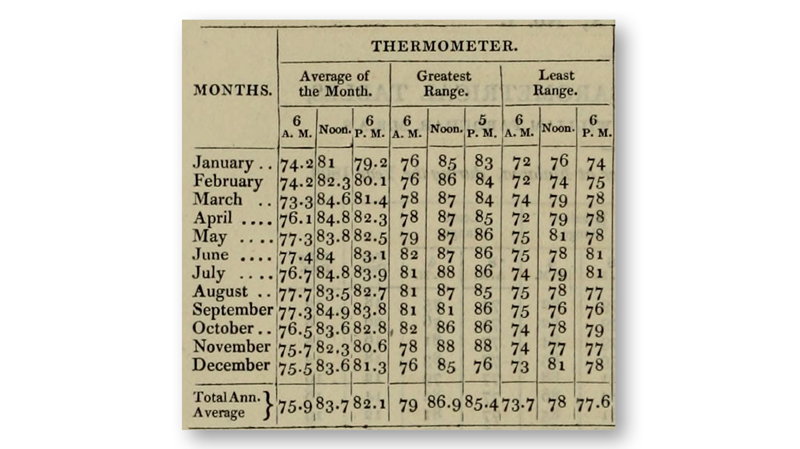

The earliest known weather observations were conducted by the settlement’s first Resident, William Farquhar, who personally recorded the monthly temperature and number of rainy days on Government Hill (present-day Fort Canning) between 1820 and 1823. After Farquhar left Singapore in 1823, this practice continued for another two years before it was stopped.

The earliest known weather observations in Singapore were carried out by the first Resident, William Farquhar, between 1820 and 1823. This table shows the temperature readings for 1822. The highest temperature recorded that year was 89°F (31.7°C) and the lowest 73°F (22.8°C). Image reproduced from Farquhar, W. (1827). Thermometrical and Barometrical Tables (p. 585). Transactions of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. London: Parbury, Allen, & Co. Collection of the National Library, Singapore (Accession no.: B29032746K).

The earliest known weather observations in Singapore were carried out by the first Resident, William Farquhar, between 1820 and 1823. This table shows the temperature readings for 1822. The highest temperature recorded that year was 89°F (31.7°C) and the lowest 73°F (22.8°C). Image reproduced from Farquhar, W. (1827). Thermometrical and Barometrical Tables (p. 585). Transactions of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. London: Parbury, Allen, & Co. Collection of the National Library, Singapore (Accession no.: B29032746K).

In the following years, several others attempted their own recordings. From November 1839 to February 1841, American missionary Joseph S. Travelli recorded the island’s temperature and rainfall from the mission school run by the American Board of Foreign Missions located on Ryan’s Hill (today’s Bukit Pasoh). Second-Lieutenant Charles Morgan Elliot of the Madras Engineers did the same between January 1841 and September 1845 from an observatory along the Kallang River. Magistrate of Police Jonas Daniel Vaughan, who had an active interest in science, kept a series of reports that ran from 1862 to 1866. He conducted his observations on River Valley Road using a self-reading thermometer and a rain gauge.2

In 1869, the government formally institutionalised the routine observation of Singapore’s weather patterns. This was led by the Medical Department of the Straits Settlements, which wanted data to establish a relationship between the weather and epidemics. The department believed that “the health of Singapore is dependent on its rainfall” and linked the outbreak of vector- and water-borne diseases such as cholera to the amount of rainfall the island received.3

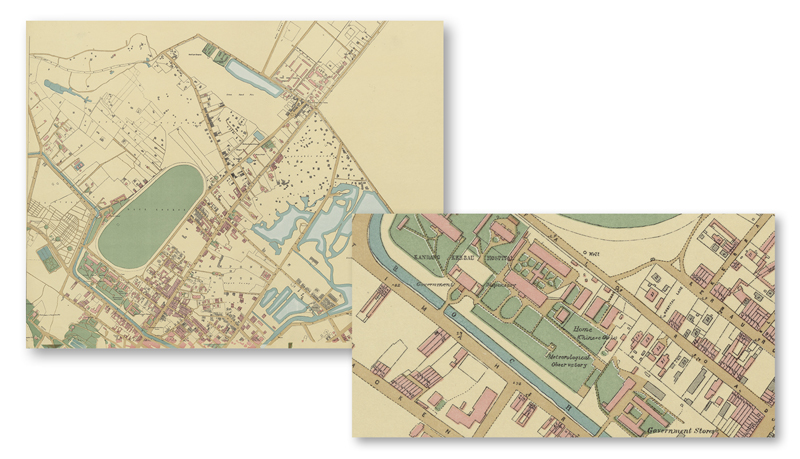

The department began compiling temperature and rainfall readings taken by observation stations located in hospitals such as the Convict Jail Hospital in Bras Basah, Kandang Kerbau Hospital, and the General Hospital at Sepoy Lines. The department also relied on readings recorded by stations maintained by private individuals, estate owners and other government departments. These stations were located mainly in the southern and central parts of Singapore, such as Mount Pleasant, Perseverance Estate in Geylang, the P&O (Peninsula and Oriental Steam Navigation Company) Depot in New Harbour, the Botanic Gardens, Killiney Estate, St John’s Island and the Waterworks Reservoir (today’s MacRitchie Reservoir).

By the end of the 1800s, there were 11 observation stations scattered across Singapore and 34 others in Penang and Melaka. Weather observations in these two territories began in 1883.4

Singapore’s weather data compiled by the Medical Department of the Straits Settlements from 1869 to 1926 was based on readings taken by various observation stations across the island. This 1893 survey map shows the location of one of the stations within the compounds of Kandang Kerbau Hospital. Survey Department, Singapore, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Singapore’s weather data compiled by the Medical Department of the Straits Settlements from 1869 to 1926 was based on readings taken by various observation stations across the island. This 1893 survey map shows the location of one of the stations within the compounds of Kandang Kerbau Hospital. Survey Department, Singapore, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The Malayan Connection

The Medical Department collated weather data for Singapore, Penang and Melaka – the colonies making up the Straits Settlements – until the end of 1926 when responsibility was transferred to the Survey Department. This was in anticipation of the formation of a dedicated meteorological branch to be overseen by the Survey Department.

In 1929, the Malayan Meteorological Service was formally established and tasked to observe the weather of the Straits Settlements and British Malaya as well as carry out a systematic and scientific study of the climate. The new office would conduct weather forecasts, prepare synoptic charts5 and organise regular observations of the earth’s upper atmosphere.6

The idea to set up a meteorological branch was first mooted by William George Maxwell, Chief Secretary of the Federated Malay States, and Herbert Robinsons, Director of the Federated Malay States Museums. The two men wanted to improve the quality of meteorological services so that more complex weather information such as weather forecasts and daily reports could be provided to the aviation sector, which was in its infancy at the time.7

Before the meteorological branch could be formed though, new full-scale observation stations had to be set up in Singapore and the Malay Peninsula. These stations were staffed by full-time observers and equipped with self-recording instruments capable of recording hourly readings of elements like temperature, humidity, rainfall, cloud formation, amount of sunshine, wind, barometric pressure, visibility, evaporation and thunderstorms (duration and intensity).8 The older observation stations were subsequently downgraded to auxiliary stations.

In 1929, the first full-scale observation station in Singapore was established on Mount Faber. Singapore was also made the headquarters of the Malayan Meteorological Service with the office located in Fullerton Building. In 1934, the Mount Faber station as well as the headquarters were moved to Kallang Airport, which the authorities thought was a more suitable location for observing Singapore’s weather and for the transmission of weather information to aircraft.9

Using weather data gathered by 17 full-scale observation stations and over 30 auxiliary stations in Malaya and Singapore, the meteorological service supplied daily weather reports to local newspapers and carried out weather forecasts for both civil and military aviation. In the mid-1930s, the Malayan Meteorological Service was described as “fast becoming one of the best organised in the East”.10

In 1938, the Malayan Meteorological Service began measuring wind speed and direction in the upper atmosphere using pilot balloons.11 It also shared synoptic weather information of Singapore and British Malaya with ships at sea as well as with the meteorological services in the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia), French Indochina (Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos), Siam (Thailand), Hong Kong, the Philippines and India.12

During the Japanese Occupation (1942–45), the Malayan Meteorological Service continued with its work. Unfortunately, weather records collected during the Occupation years were destroyed by the Japanese before they surrendered. In addition, almost all the meteorological instruments and equipment were damaged beyond repair. It took about two years after the end of the war before the Met Service was able to resume full operations.13

After the war, the Malayan Meteorological Service ceased to be part of the Survey Department and instead functioned as a separate government department that served both Singapore and the Federation of Malaya. In addition to its regular duties, the service also exchanged meteorological information with regional met offices and the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO). The latter was an intergovernmental organisation set up by the United Nations in 1950 to facilitate cooperation and the sharing of weather data among member nations.14

The Malayan Meteorological Service also began acquiring new equipment to better capture weather-related data. In 1951, it installed the first weather radar sets in Singapore, Kuala Lumpur and Kota Baru to track the occurence and movement of thunderstorms in the region. The following year, it established an upper air observatory in Paya Lebar. This was significant as the upper air observatory enabled the tracking of temperature and humidity in order to determine the vertical profile of the atmosphere.15

From the mid-1950s, the Malayan Meteorological Service began using merchant shipping vessels to gather weather data. These ships were equipped with meteorological instruments so that they could capture weather information along the Straits of Melaka and in the South China Sea. By the end of the decade, the service was managing 10 full-scale meteorological stations in the Federation of Malaya and one in Singapore. This was in addition to a network of 43 auxiliary stations in the Federation and another 24 in Singapore.16

Yang di-Pertuan Negara Yusof Ishak peering into a weather apparatus at Paya Lebar Airport, 1961. Yusof Ishak Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Yang di-Pertuan Negara Yusof Ishak peering into a weather apparatus at Paya Lebar Airport, 1961. Yusof Ishak Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Flying Solo

After Singapore gained independence in 1965, the Meteorological Service Singapore (MSS) was formed when the Singapore section of the Malayan Meteorological Service – comprising the main observation station in Paya Lebar and 30 auxiliary stations – was hived off and briefly came under the purview of the Deputy Prime Minister’s Office before being transferred to the Ministry of Communications in 1968.17 During this time, Singapore also officially became a member of the WMO in 1966.18

The MSS continued acquiring new equipment to improve its ability to gather data and carry out forecasting. In 1970, the MSS replaced its storm warning radar at Paya Lebar Airport with one that could detect storms up to 400 km away. Its radar waves could penetrate places receiving heavy rainfall, which enabled the service to obtain a more detailed picture of the distribution of rain areas.19 In 1971, the MSS replaced its upper air-sounding system and opened a new ground station at its headquarters in Paya Lebar Airport to receive up-to-date satellite meteorological imagery of Southeast Asia.

These boys made quick money from the driver by pushing his stalled pick-up truck along flooded Tiong Bahru Road on 7 December 1976. Several low-lying areas in Singapore were similarly flooded due to a heavy storm. Source: The Straits Times © Singapore Press Holdings Limited. Reprinted with permission.

These boys made quick money from the driver by pushing his stalled pick-up truck along flooded Tiong Bahru Road on 7 December 1976. Several low-lying areas in Singapore were similarly flooded due to a heavy storm. Source: The Straits Times © Singapore Press Holdings Limited. Reprinted with permission.

The MSS also began deploying aircraft as mobile weather observations. From 1979, an electronic device known as Aircraft to Satellite Data Relay was installed in Singapore Airlines planes to record temperature, wind and pressure conditions outside the aircraft. The system could also track the aircraft’s altitude and location every seven-and-a-half minutes. The information was then automatically transmitted to ground-receiving stations via geostationary satellites so that the MSS could provide better services to the aviation industry, especially for aircraft on long-haul routes.20

In 1981, the MSS introduced a new weather radar system to track rain better. Located at Changi Airport, which became the headquarters of the department in 1983,21 the radar system also provided advance warning of adverse weather conditions. It could even measure the total amount of rainfall in any part of Singapore during a storm.22

• Highest daily maximum temperature: 37°C (Tengah Station, 17 April 1983)

• Lowest daily minimum temperature: 19°C (Paya Lebar Station, 14 February 1989)

• Highest daily total rainfall: 512.4 mm (Paya Lebar Station, 2 December 1978)

• Highest monthly total rainfall: 996.3 mm (Buangkok Station, December 2006)

• Maximum wind gust: 90.7 km/h (Changi Climate Station, 29 November 2010)

REFERENCE

Meteorological Service Singapore. (2020, February 12). Historical extremes. Retrieved from Meteorological Service Singapore website.

The MSS also launched a multimillion-dollar computerisation programme to replace time-consuming, labour-intensive work such as the compilation of meteorological data, and the preparation and updating of weather charts. Johnny Tan, a technical officer with the MSS, told The Straits Times that the work he used to do was “tedious” and involved “decoding pages of numbers and plotting tiny figures onto weather charts day in and day out…”.23 Because of his work at the MSS, Tan had to start wearing glasses. With the help of computers, however, charts that Tan used to take four or five hours to plot could be done by the computer in just eight minutes.

Throughout the 1990s, the MSS continued to expand its capabilities with new meteorological equipment. In 1996, the MSS established a national seismic system to detect an earthquake within minutes of its occurrence. The system, which is still in use today, can also estimate the location of the earthquake and measure its intensity and magnitude. This information is shared with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Earthquake Information Center based in Jakarta.24

In 1997, the MSS installed a lightning detection system to track and detect lightning activities between clouds as well as lightning that strikes the ground. (Interestingly, Singapore has one of the highest occurences of lightning activity in the world.) This allows the MSS to generate accurate maps showing lightning activity. Before this, the MSS was only able to estimate the location of lightning strikes.

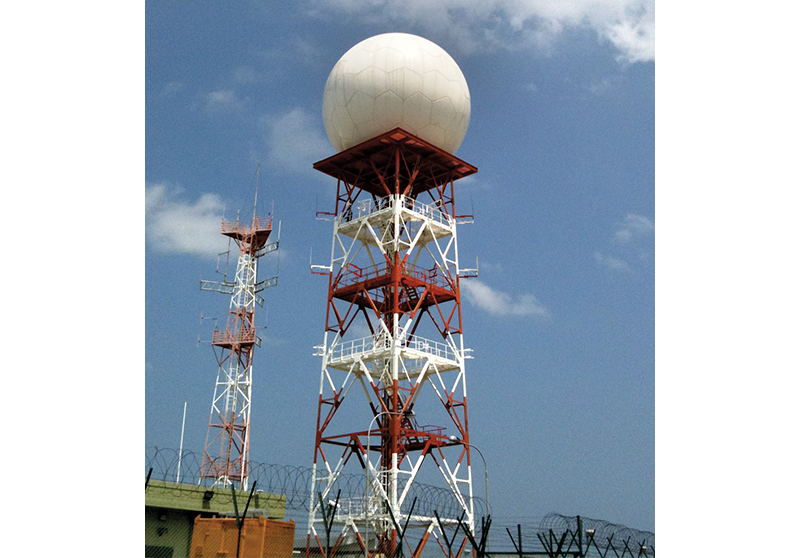

That same year, the MSS replaced the weather radar installed in 1981 with a Doppler radar. While the older radar could only measure the intensity of precipitation, the new radar was able to measure the velocity of raindrops moving towards or away from the radar, thus allowing it to compute wind speeds during a storm.25

One of the most important tools used by the Meteorological Service Singapore to study the weather is the Doppler weather radar shown here, which is able to detect the motion of rain droplets, measure the intensity of precipitation and estimate wind strengths. The data allows meteorologists to monitor the development and movement of weather systems and to analyse the structure of a storm. Courtesy of the Meteorological Service Singapore.

One of the most important tools used by the Meteorological Service Singapore to study the weather is the Doppler weather radar shown here, which is able to detect the motion of rain droplets, measure the intensity of precipitation and estimate wind strengths. The data allows meteorologists to monitor the development and movement of weather systems and to analyse the structure of a storm. Courtesy of the Meteorological Service Singapore.

Apart from upgrading equipment, the MSS also improved the way it delivered weather information to the public. Soon after Teletext – a television information retrieval service – was launched in 1983, weather information was made available on the platform. The following year, the MSS introduced a 24-hour telephone service whereby people could obtain 12-hour weather forecasts, tide times, and the highest and lowest temperatures expected.26 A decade later, the MSS launched METFAX so that the public could retrieve graphic weather charts by fax.

In 1995, the MSS launched a website featuring its own weather satellite images as well as those by the US National Oceanographic Atmospheric Administration.27 That same year, the MSS became the Operational Meteorological Databank for Southeast Asia, a responsibility it continues to assume today. This databank facilitates the exchange of operational meteorological data between countries in the Asia-Pacific and Europe.

The MSS was also appointed to host the ASEAN Specialised Meteorological Centre (ASMC). Set up in 1993, the ASMC – which is still active today – aims to support the development of national meteorological services in ASEAN. After the ASEAN Regional Haze Action Plan was implemented in 1997, the ASMC was designated by the environment ministers of ASEAN member states as the centre responsible for the monitoring of land and forest fires, and the assessment and provision of advisories of transboundary haze in the southern ASEAN region.28

A Leading Meteorological Service

The MSS became part of the National Environment Agency (NEA) in 2002, under the auspices of the Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources (MEWR).

In 2010, the Doppler weather radar in use since 1997 was replaced with an even more powerful version that can track the movement and intensity of precipitation within a radius of 480 km. With this, the MSS is able to provide a more accurate estimate of expected rainfall. In turn, this data can be used for better water resource and flood management. The improved data also enables the Met Service to prepare detailed en-route weather forecasts for flights as well as issue advisories and warnings of adverse weather conditions.29

Records show that Singapore’s mean temperature has been increasing from about the mid-1970s, which is when Singapore embarked on its rapid phase of urbanisation. The hotter weather could also have been influenced by regional variations in the man-made global warming effect, according to the Meteorological Service Singapore.

REFERENCES

Meteorological Services Malaya and Singapore. (1966). Summary of observations for Malaya, Singapore, Sabah and Sarawak. Singapore: G.P.O. (Call no.: RCLOS 551.5 MAL)

Singapore Meteorological Service. (1967–1994). Summary of observations. Singapore: G.P.O. (Call no.: RSING 551.5 SMSSO)

To keep pace with the way people consume information today, the MSS launched the Weather@SG mobile website in 2009, followed by the Weather@SG mobile app in 2016 so that the public can obtain information such as island-wide observations of rainfall, temperature, humidity, wind direction and location-specific forecasts on-the-go.30

The MSS has also been strengthening its research base by building up local expertise in climate science and expanding its collaboration with regional institutes. In 2011, the Met Service signed a memorandum of understanding with the Meteorological Office of the United Kingdom to develop climate models that could make long-term projections of Singapore’s climate for various time scales up to the year 2100.

The following year, the MSS established the Centre for Climate Research Singapore (CCRS). This is the first centre in the world to focus on the understanding and prediction of tropical weather and climate. The CCRS also aims to develop research expertise in the areas of weather and climate for Singapore and Southeast Asia.

Under the Second National Climate Change Study released in early 2015, the CCRS carried out climate projections up to the year 2100 and beyond for variables such as rainfall, wind, temperature and rising sea levels to better understand climate change and support Singapore’s climate resilience and adaptation planning. To understand how the current climate and its variability affect Singapore and the region, the CCRS uses dynamical climate models31 and the latest statistical modelling techniques to produce seasonal forecasts of temperature and rainfall that are useful in managing water resources and public health. It has also conducted studies to improve the understanding of key weather and climate conditions such as the Sumatra squalls and the El Niño phenomenon.32

In July 2019, the MEWR announced that a Climate Science Research Programme Office would be set up in 2020 under the CCRS to lead and drive Singapore’s national climate science research masterplan. The programme office will focus on pressing climate issues such as the rise in sea levels, the impact of climate change on Singapore’s water resources, and the impact of rising temperatures on human health and the energy sector. Environment and Water Resources Minister Masagos Zulkifli said that the programme office would “work closely with scientists and researchers in [Singapore’s] research institutes and universities to harness their expertise for cutting-edge climate science research”.33

The author would like to thank the Meteorological Service Singapore, especially Ms Patricia Ee, Director of the Weather Services Department, for reviewing this article.

Lim Tin Seng is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. He is the co-editor of Roots: Tracing Family Histories – A Resource Guide (2013), Harmony and Development: ASEAN-China Relations (2009) and China’s New Social Policy: Initiatives for a Harmonious Society (2010). He writes regularly for BiblioAsia.

Lim Tin Seng is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. He is the co-editor of Roots: Tracing Family Histories – A Resource Guide (2013), Harmony and Development: ASEAN-China Relations (2009) and China’s New Social Policy: Initiatives for a Harmonious Society (2010). He writes regularly for BiblioAsia.

NOTES

-

Singapore’s average sea level now 14 cm higher than ‘pre-1970 levels’: Met Service. (2020, March 23). CNA. Retrieved from Channel NewsAsia website. ↩

-

Farquhar, W. (1827). Thermometrical and barometrical tables (pp. 585–586). Transactions of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. (Call no.: RRARE 551.609595 FAR; Accession no.: B29032746K); Malayan Meteorological Service. (1950). Annual report of the Malayan Meteorological Service, 1949 (p. 5). Singapore: G.P.O. (Call no.: RCLOS 551.5 MAL); Crawfurd, J. (1830). Journal of an embassy from the governor-general of India to the courts of Siam and Cochin China (Vol. II) (p. 345). London: H. Colburn and R. Bentley. (Call no.: RRARE 959.7 CRA; Microfilm no.: NL11335; Accession nos.: B29033764A; B29033766C); Makepeace, W., Brooke, G.E., & Braddell, R.S.J. (Eds.). (1991). One hundred years of Singapore (Vol. II) (pp. 478–479). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 ONE-[HIS]); Buckley C.B. (1984). An anecdotal history of old times in Singapore 1819–1867 (pp. 735–741). Singapore: Oxford University Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 BUC-[HIS]); Wheatley, J.J.T. (1881, June). Notes on the rainfall in Singapore. Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 7, 31–50, pp. 31–32. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website; Straits Settlements Government. (1865, January 20). Straits Settlements Government Gazette (p. 20). Singapore: Government Printing Press. (Call no.: RRARE 959.51 SGG; Microfiilm no.: NL1003) ↩

-

Malayan Meteorological Service, 1950, p. 5; The rainfall. (1874, May 16). Straits Times Overland Journal, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Straits Settlements Government. (1874, May 2). Straits Settlements Government Gazette (pp. 252–253). Singapore: Government Printing Press. (Call no.: RRARE 959.51 SGG; Microfilm no.: NL5349); Williamson, F., & Wilkinson, C. (2017). Asian extremes: Experience and exchange in the development of meteorological knowledge c. 1840–1930. History of Meteorology, 8, 159–178, p. 169. Retrieved from Singapore Management University website; Straits Settlements Government. (1901, May 17). Straits Settlements Government Gazette (p. 828). Singapore: Government Printing Press. (Call no.: RRARE 959.51 SGG; Microfilm nos.: NL1044–1048); Straits Settlements Government. (1905, March 10). Straits Settlements Government Gazette (p. 524). Singapore: Government Printing Press. (Call no.: RRARE 959.51 SGG; Microfilm nos.: NL1051–1068) ↩

-

A synoptic chart is a map that shows weather patterns over an area by putting together many weather reports from different locations all taken at the same moment in time. ↩

-

Survey Department. (1928). Survey Department, Straits Settlements. In Annual Departmental Reports of the Straits Settlements for the year 1927 (p. 84). Singapore: Government Printing Press. (Call no.: RRARE 325.3410959 SSADRS; Microfilm nos.: NL396–397) ↩

-

Aids to aviation in Malaya. (1929, May 18). The Straits Times, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Survey Department, 1928, p. 84; Malayan Meteorological Service, 1950, pp.9-10. ↩

-

Survey Department. (1931). Survey Department, Straits Settlements. In Annual Departmental Reports of the Straits Settlements for the year 1930 (p. 4). Singapore: Government Printing Press. (Call no.: RRARE 325.3410959 SSADRS; Microfilm nos.: NL397; NL622); Malayan Meteorological Service. (1931). Summary of Observations, 1930 (pp. 1–2). Singapore: Malayan Meteorological Service. (Microfilm no.: NL7550) ↩

-

Survey Department. (1932). Survey Department, Straits Settlements. In Annual Departmental Reports of the Straits Settlements for the year 1931 (p. 18). Singapore: Government Printing Press. (Call no.: RRARE 325.3410959 SSADRS; Microfilm no.: NL2921) ↩

-

Malaya knows all weather. (1935, September 16). The Straits Times, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 16 Sep 1935, p. 13; Malayan Meteorological Service, 1950, p.10; Balloon goes up for the weather men. (1938, February 27). The Straits Times, p. 28. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Making Malaya’s air routes safe forecasting Malaya’s weather. (1936, June 20). Morning Tribune, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Malayan Meteorological Service, 1950, p. 11; Weather men back at work in Malaya. (1947, June 29). The Straits Times, p. 6; World’s most modern weather forecast aids for Singapore. (1938, August 21). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Malayan Meteorological Service, 1950, p. 11; Singapore Meteorological Service. (1995). Annual report 1994 (pp. 18–19). (Call no.: RSING 551.5095957 SMSAR); Malayan Meteorological Service. (1952). Annual report of the Malayan Meteorological Service, 1951 (p. 1). Singapore: G.P.O. (Call no.: RCLOS 551.5 MAL); Colony of Singapore. (1959). Annual report, 1958 (pp. 253–254). Singapore: G.P.O. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.57 SIN); Singapore Meteorological Service, 1995, p. 22. ↩

-

Malayan Meteorological Service. (1953). Annual report of the Malayan Meteorological Service, 1952 (p. 2). Singapore: G.P.O. (Call no.: RCLOS 551.5 MAL); Malayan Meteorological Service. (1958). Annual report of the Malayan Meteorological Service, 1957 (p. 4). Singapore: G.P.O. (Call no.: RCLOS 551.5 MAL); Weather report from 60,000 ft. (1952, August 21). Singapore Standard, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Malayan Meteorological Service, 1953, p. 2; Malayan Meteorological Service, 1958, pp. 4–5; Singapore Standard, 21 Aug 1952, p. 3; State of Singapore. (1960). Annual report, 1959 (p. 263–264). Singapore: G.P.O. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.57 SIN) ↩

-

Separation causes S’pore to spend extra $6.4m. (1965, December 14). The Straits Times, p. 15. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Meteorological Services Malaya and Singapore. (1966). Summary of observations for Malaya, Singapore, Sabah and Sarawak (p. i). Singapore: G.P.O. (RCLOS 551.5 MAL); National Archives of Singapore. (n.d.). Ministry of Communications: Administrative history. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website; Ministry of Culture. (1968, August 2). Visit of Mr. Yong Nyuk Lin, Minister for Communications, to Meteorological and Marine Departments on Friday, 2nd August, 1968. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

World Meteorological Organization. (n.d.). Country profile database: Singapore. Retrieved from World Meteoroglocial Organization website. ↩

-

$500,000 weather radar for Paya Lebar. (1970, April 17). The Straits Times, p. 16. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ministry of Culture. (1970, December 2). Speech of Mr. Yong Nyuk Lin, Minister for Communications, at the official opening of the World Meteorological Organisation training seminar on synoptic analysis and forecasting in the tropics of Asia and Southwest Pacific at the Cultural Centre on Wednesday 2/12/70 @ 1000 hours. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website; The Straits Times, 17 Apr 1970, p. 16; Latest weather forecast gear for our airport. (1970, December 3). The Straits Times, p. 2; S’pore may have new $1.5m weather system. (1977, March 9). The Business Times, p. 2; Gear to help weathermen. (1979, March 17). The Business Times, p. 2; Weather dept’s new device for aircraft. (1979, March 17). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore Meteorological Service, 1995, pp. 18–19. ↩

-

Singapore plans met satellite station. (1978, May 18). The Straits Times, p. 10; Weather radar system. (1979, December 15). The Business Times, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Koh, N. (1986, February 24). High-tech forecasts. The Straits Times, p. 1; Lee, J. (1985, July 2). Halving the time taken for weather forecasts. Singapore Monitor, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore Meteorological Service. (1997). Annual report 1996 (pp. 13, 17). (Call no.: RSING 551.5095957 SMSAR); Seismic stations for S’pore. (1995, April 18). The Straits Times, p. 28. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Yeo, S. (1997, March 24). Met offers lightning service. The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Singapore Meteorological Service. (1999). Annual report 1997/98 (p. 12). (Call no.: RSING 551.5095957 SMSAR) ↩

-

Wang, L.K. (1982, March 20). Teleview may be ready by 1986/87, says Teng Cheong. The Business Times, p. 1; Enter the era of instant information. (1983, July 31). Singapore Monitor, p. 18. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Ministry of Culture. (1984, July 4). Speech by Dr. Yeo Ning Hong, Minister for Communications and Second Minister of Defence, at the launching of the Dial-A-Weather-Forecast Service at the PSA Auditorium. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Singapore Meteorological Service, 1995, p. 14; Singapore Meteorological Service. (1996). Annual report 1995 (p. 7). (Call no.: RSING 551.5095957 SMSAR); Singapore Meteorological Service, 1999, p. 8; Weather report on Internet. (1995, November 11). The Straits Times, p. 30. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore Meteorological Service, 1995, p. 22; Tan, C.H. (2012). Safeguard, nurture, cherish our environment (p. 126). Singapore: National Environment Agency. (Call no.: RSING 363.7095957 TAN); ASEAN Specialised Meteorological Centre. (2020). About ASMC. Retrieved from ASEAN Specialised Meteorological Centre website. ↩

-

Tan, 2012, pp. 127, 197; Free phone app to track weather changes in S’pore. (2016, March 23). Today. Retrieved from Today’s website. ↩

-

A dynamical climate model uses the physics of the oceans, atmosphere, land and ice and the multiple complex interactions between them to estimate the most likely average climate state for several months ahead. ↩

-

Centre for Climate Research Singapore. (2015). Mission & vision. Retrieved from Centre for Climate Research Singapore website; Centre for Climate Research Singapore. (2015). Research areas. Retrieved from Centre for Climate Research Singapore website. ↩

-

Elangovan, N. (2019, July 17). New research office to boost Singapore’s climate science capabilities: Masagos. Today. Retrieved from TODAYonline. ↩