Sang Nila Utama: Separating Myth From Reality

The Malay prince who founded Singapura in the 13th-century is a controversial figure – depending on which account of the Sejarah Melayu you read, says Derek Heng.

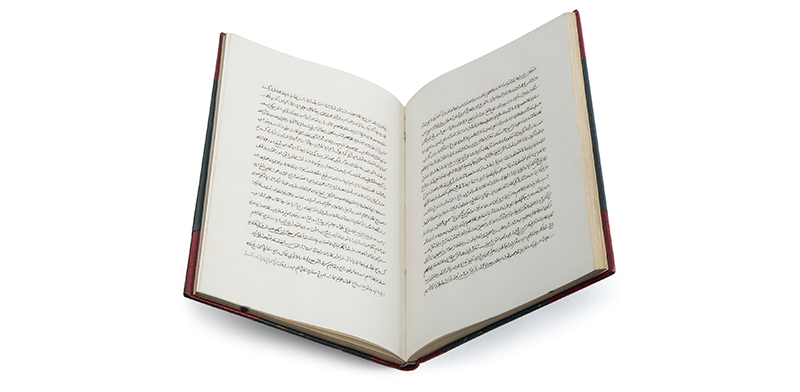

The title page of John Leyden’s English translation of the Sejarah Melayu (Malay Annals), which was published posthumously in London in 1821. It includes an introduction by Stamford Raffles. Leyden was a Scottish poet and linguist who spoke several languages, including Malay. Collection of the National Library, Singapore (Accession no.: B02633069G).

The title page of John Leyden’s English translation of the Sejarah Melayu (Malay Annals), which was published posthumously in London in 1821. It includes an introduction by Stamford Raffles. Leyden was a Scottish poet and linguist who spoke several languages, including Malay. Collection of the National Library, Singapore (Accession no.: B02633069G).

The 17th-century Sulalat al-Salatin1 (Genealogy of Kings), better known as Sejarah Melayu or Malay Annals, holds an important place in the imagination and collective memory of Singaporeans. Its first six chapters – which focus on Singapore – provide a mythical narrative of the port-polity of Singapura in the late 13th and 14th centuries, and also places Singapore in the larger pre-modern and early modern Malay world. It links the island to the histories of important kingdoms such as Melaka and Johor, Pasai on the north coast of Sumatra, the Majapahit empire on Java and Ayutthaya in Siam (now Thailand), to name but a few.

The text mentions a number of characters, including Alexander the Great of Macedonia; Raja Chulan of the Chola dynasty in South India; Sang Nila Utama, a Sriwijayan prince from Palembang; and Badang,2 the champion of Singapura who possessed supernatural strength.

Among these, the character who probably looms the largest in the Singaporean imagination is Sang Nila Utama, the mythical prince of Palembang who founded the city of Singapura on the island of Temasik (Temasek) around 1299, about a century prior to the founding of Melaka by his descendant.

As no other historical document or evidence corroborates the founding of Singapore as described in the Sejarah Melayu, the account – and the character – occupies the ambiguous space between history and myth. However, Sang Nila Utama is more than just a mythical character who founded Singapura – the precursor to the illustrious Melaka Sultanate (1400–1511). The character “Sang Nila Utama” was used to create a genealogy for the rulers of Melaka, and provided the means by which political legitimacy, the role of political charisma and the expansion of the sphere of influence of the Melakan rulers could be articulated.

Sang Nila Utama also provided the means by which a revisionist history of the founding of Melaka could be effected and, in the process, elevate the stature of the Melakan royal lineage. In short, the character – while seemingly benign and cloistered in the pre-modern and primordial myths of the Malay region – in fact served a critical and real-world purpose of historical discourse in the context of the Melaka Straits region in the late 16th and early 17th centuries.

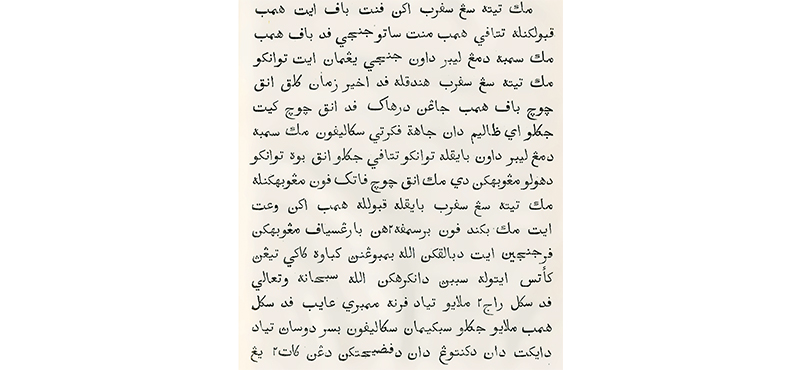

To understand the role played by Sang Nila Utama, we will examine his origins as outlined in two major variants of the Sejarah Melayu (as many as 30 variants have been identified by scholars so far). The first is the John Leyden version,3 which was transcribed and translated from Jawi into English around 1810 and published posthumously in 1821.4 The second is the Raffles Manuscript (MS) 18, based on the earliest version of the text (dated 1612) and likely transcribed for Stamford Raffles in 1816.5 While the overarching narratives in both versions are similar, certain minor differences exist regarding the stories they tell of Sang Nila Utama.

The Raffles MS 18 version of the Sejarah Melayu is based on the earliest edition of the text (dated to 1612) and likely transcribed for Stamford Raffles in 1816. This publication can be accessed on the National Library’s BookSG portal. Courtesy of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom.

The Raffles MS 18 version of the Sejarah Melayu is based on the earliest edition of the text (dated to 1612) and likely transcribed for Stamford Raffles in 1816. This publication can be accessed on the National Library’s BookSG portal. Courtesy of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom.

Who was Sang Nila Utama?

The Sejarah Melayu begins with Alexander the Great of Macedonia (also known as Iskandar Shah or Secander Zulkarneini) embarking on a military expedition to the Indian subcontinent. He married a princess of one of the pacified kingdoms and from that union came a series of rulers, culminating in Raja Chulan, the ruler of the Chola kingdom in South India. In the Sejarah Melayu, Raja Chulan set off on a military campaign across the Bay of Bengal and arrived at the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula. There, according to legend, he descended below the sea where he married the princess of the marine people. They had three sons who, as young princes, descended from heaven and appeared on the sacred hill of Bukit Seguntang in Palembang.

This is where the accounts in the two versions of the Sejarah Melayu differ. In the Leyden version, Bichitram Shah, one of the three young princes who identified himself as raja, was conferred the name Sang Sapurba. He became the ruler of Palembang following the abdication of the erstwhile local ruler, Demang Lebar Daun. Sang Sapurba’s political legitimacy was further sealed by his marriage to Demang Lebar Daun’s daughter. Among their children was Sang Nila Utama, who later married the daughter of the queen of Bentan (now Bintan) and became its raja. Sang Nila Utama eventually went on to found Singapura, upon which he was conferred the title Sri Tri Buana.

According to the Sejarah Melayu, the ruler of Palembang, Demang Lebar Daun, concluded a covenant with Sang Nila Utama which stated that in return for the undivided loyalty of his subjects, Sang Nila Utama and all his descendants would be fair and just in their rule. This extract is from the 1840 edited version by Munsyi Abdullah. Collection of the National Library, Singapore (Accession no.: B31655050C).

According to the Sejarah Melayu, the ruler of Palembang, Demang Lebar Daun, concluded a covenant with Sang Nila Utama which stated that in return for the undivided loyalty of his subjects, Sang Nila Utama and all his descendants would be fair and just in their rule. This extract is from the 1840 edited version by Munsyi Abdullah. Collection of the National Library, Singapore (Accession no.: B31655050C).

In the Raffles MS 18 version, the three princes – Bichitram, Paludatani and Nilatanam – were each appointed ruler of a kingdom in the Malay world. The eldest, Bichitram, became the ruler of the Minangkabau in western Sumatra and was titled Sang Sapurba. The second son, Paludatani, was invited by the people of Tanjong Pura in western Kalimantan to be their ruler and given the title Sang Maniaka. The youngest prince, Nilatanam, remained at Palembang in southeastern Sumatra and was made raja there and given the title Sang Utama.

Nilatanam became the ruler of Palembang following the abdication of Demang Lebar Daun. After his marriage to the latter’s daughter, a ritual bath and coronation ceremony were carried out, and he was conferred the title Sri Tri Buana. Sri Tri Buana subsequently travelled to Bentan and thence to Temasik, where he founded the port-city of Singapura.6

In summary, in the Leyden version, Sang Nila Utama is the child of a union between Sang Sapurba (Raja Chulan’s son) and the daughter of Demang Lebar Daun. In the Raffles MS 18 version, Sang Nila Utama is the son of Raja Chulan himself, while Sang Sapurba is Sang Utama’s brother. In this version, it is Sang Utama who marries the daughter of Demang Lebar Daun.

Sang Nila Utama Secondary School on Upper Aljunied Road, 1968. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Sang Nila Utama Secondary School on Upper Aljunied Road, 1968. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.In Singapore, Sang Nila Utama was memorialised in a school named after him. Formerly located on Upper Aljunied Road, the now-defunct Sang Nila Utama Secondary School officially opened in 1961 and ceased operations in 1988. Its alumni include Yatiman Yusof and Mohamad Maidin, both former members of parliament. Well-known writer Masuri Salikun (also known as Masuri S.N.) once taught at the school.

Sang Nila Utama Secondary School was significant because it was Singapore’s first Malay-medium secondary school. It was also the third secondary school built after Singapore attained self-government in 1959.

From 1965, the school added two Malay-medium pre-university classes to the existing secondary classes. Three years later, it started two English-medium secondary classes. However, the school stopped conducting pre-university classes from 1979 in line with the Ministry of Education’s decision to phase out non-English pre-university centres by 1981. Only two Malay-stream secondary classes remained in 1984.

By 1988, Sang Nila Utama Secondary School had ceased operations due to falling enrolment. The school building has since been demolished to make way for Bidadari housing estate, on the site of the former Bidadari Cemetery.

Although the school no longer exists, the name Sang Nila Utama will live on in two roads. In November 2019, Deputy Prime Minister Heng Swee Keat announced that a road in the Bidadari estate – located next to the site of the former Sang Nila Utama Secondary School – will be named Sang Nila Utama Road. “This is something that the Malay community has been asking for, because of the important role that Sang Nila Utama Secondary School played in developing Malay education in Singapore,” he said.

A section of the new Heritage Walk cutting across the 10-hectare Bidadari Park in the estate will be called Sang Nila Utama Boulevard. This is the current Upper Aljunied Road, which is now pedestrianised. The housing estate and park are slated to be completed by 2022.

Sang Nila Utama is also memorialised by way of the Sang Nila Utama Garden in Fort Canning Park. Launched in 2019, the garden is a re-creation of Southeast Asian gardens of the 14th century.

Artefacts recovered from the first excavation carried out in 1984 on the eastern slope of Fort Canning Hill, near the Keramat Iskandar Shah, point to the existence of a late-13th to 14th-century settlement on the hill, as eulogised in the Sejarah Melayu. Daoyi zhilue (岛夷志略; Description of the Barbarians of the Isles) by the 14th-century Chinese traveller Wang Dayuan (汪大渊) mentions two trading settlements on Temasik: Banzu, located on and around Fort Canning Hill, and Longyamen (present-day Keppel Straits). (Far left) Fragment of a stem-cup excavated from Fort Canning Hill. Image reproduced from Kwa, C.G., Heng, D., Borschberg, P., & Tan, T.Y. (2019). Seven Hundred Years: A History of Singapore (p. 36). Singapore: National Library Board and Marshall Cavendish International. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 KWA-[HIS]). (Middle and right) A blue-and-white stem-cup (top and side views). Collection of the Asian Civilisations Museum.

Artefacts recovered from the first excavation carried out in 1984 on the eastern slope of Fort Canning Hill, near the Keramat Iskandar Shah, point to the existence of a late-13th to 14th-century settlement on the hill, as eulogised in the Sejarah Melayu. Daoyi zhilue (岛夷志略; Description of the Barbarians of the Isles) by the 14th-century Chinese traveller Wang Dayuan (汪大渊) mentions two trading settlements on Temasik: Banzu, located on and around Fort Canning Hill, and Longyamen (present-day Keppel Straits). (Far left) Fragment of a stem-cup excavated from Fort Canning Hill. Image reproduced from Kwa, C.G., Heng, D., Borschberg, P., & Tan, T.Y. (2019). Seven Hundred Years: A History of Singapore (p. 36). Singapore: National Library Board and Marshall Cavendish International. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 KWA-[HIS]). (Middle and right) A blue-and-white stem-cup (top and side views). Collection of the Asian Civilisations Museum.

Sang Nila Utama and the Genealogy of Melakan Royalty

One of Sang Nila Utama’s primary functions in the Sejarah Melayu is to provide the genealogical connections to the key classical cultures of the Malay world. The first connection is made through Sang Nila Utama’s lineage to the Chola rulers of South India through the person of Raja Chulan, which forms the link between the Melakan royalty and the Indian sub-continent. Since the late first millennium BCE, there had been continuous and intense interactions between the Malay world and this part of India.

The second connection described in the Sejarah Melayu is Raja Chulan’s genealogy that stretches all the way back to Alexander the Great and, in effect, extending the lineage of the Melakan sultans further westward to include the Hellenistic and Gandharan spheres.7

The third geographical sphere that formed the basis of the lineage of the Melaka Sultanate is the people of the deep sea, or maritime realm, which, according to the Sejarah Melayu, was located off the shores at the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula.

These three geographical spheres represented religions that were integral to the pre-Islamic Malay world. The Hellenistic/Gandharan sphere was the centre for the spread of Buddhism while the Indian sub-continent, specifically during the period of the Chola dynasty, saw the rise of Hinduism. The people of the maritime realm – with their close ties to the sea – practised the animist beliefs of the Malay region. The fact that these three religious-cultural spheres formed the basis of Melakan royal lineage is an important point made by the Sejarah Melayu.

The focal point of the genealogy in the Sejarah Melayu is where the central place of the geographical and cultural sphere of the Malay world is articulated. In this regard, the Leyden and Raffles MS 18 versions provide differing accounts.

In the Leyden version, Sang Sapurba is presented as the prime generation in the genealogy. Sang Sapurba’s ancestry could be regarded as representations of the primordial period of the past and constitutes the primary influences from the broader world that would later come to define the Malay world. Sang Sapurba’s marriage to the daughter of Demang Lebar Daun, the ruler of Palembang, is instrumental in conjoining the royal lineage of the Chola kingdom with the land-based Malays located in Andalas, also known as the lowlands of Sumatra.

Sang Sapurba’s succeeding generation cemented his lineage with those of China (one of Sang Sapurba’s daughters married the ruler of China) as well as the people of Bentan. Sang Sapurba eventually left Bentan and returned to Sumatra where he subsequently became the ruler of the Minangkabau in the highlands of Sumatra. The Leyden version of the Sejarah Melayu thus locates the central place of Melakan royalty as the Sumatran world, i.e. the lowlands of the Muara Jambi River, Palembang, the Riau-Lingga Archipelago as well as the Minangkabau highlands. Temasik, or Singapore, and subsequently Melaka, were peripheral areas that only later became the focus of the narrative.

In contrast, the Raffles MS 18 version of the Sejarah Melayu has a different central focus. In this version, Sang Utama, along with his two brothers Sang Sapurba and Sang Maniaka, are presented as the prime characters in the genealogy. Sang Utama’s lineage is regarded as a representation of the primordial past. However, in the Raffles version, all subsequent conjoining of the royal lineage occurred in Sang Utama’s generation only. The union of his lineage with the land-based Malays of lowland-coastal Sumatra is represented by his marriage to the daughter of Demang Lebar Daun, the ruler of Palembang.

Sang Utama subsequently settled first in Bentan, where he was adopted by Wan Sri Benian, the queen of Bentan, before proceeding to Temasik where he established the city of Singapura. It is only when two of Sang Nila Utama’s sons married the granddaughters of Wan Sri Benian that the orang laut8 in Bentan became linked with the royal lineage. Hence, the Raffles MS 18 version of the Sejarah Melayu places the central location of Melakan royal lineage as Palembang, the Riau Archipelago and the island of Singapore.

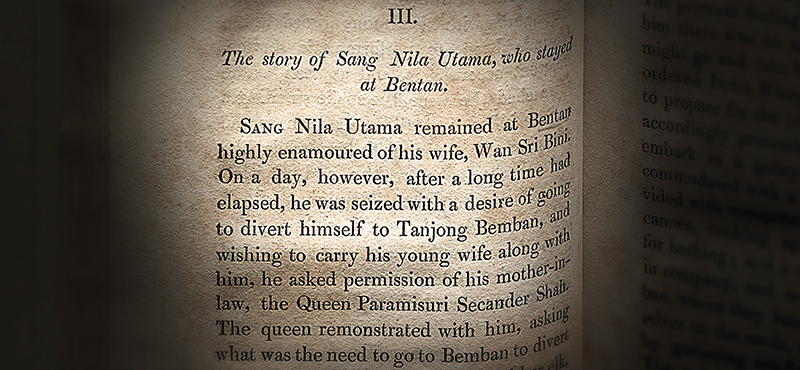

Chapter 3 of John Leyden’s English translation of the Sejarah Melayu tells the story of Sang Nila Utama and his life in Bentan (Bintan). Sang Nila Utama had married Wan Sri Bini, the daughter of the queen of Bentan. Collection of the National Library, Singapore (Accession no.: B02633069G).

Chapter 3 of John Leyden’s English translation of the Sejarah Melayu tells the story of Sang Nila Utama and his life in Bentan (Bintan). Sang Nila Utama had married Wan Sri Bini, the daughter of the queen of Bentan. Collection of the National Library, Singapore (Accession no.: B02633069G).

Why does the seat of power of the Melakan kings differ so vastly in these two accounts? In a 2001 essay, academics Virgina and Michael Hooker noted that John Leyden’s transcriptions and translations were based on the oral recitation of the Sejarah Melayu by Ibrahim Candu, a Tamil-Muslim scribe from Penang who had collected the text in Melaka and recited it to Leyden in Calcutta in 1810.9 This version, at least in terms of the narrative on the genealogy of the rulers of Melaka, is similar to that found in missionary William Girdlestone Shellabear’s 1896 translation of the text in Rumi (romanised Malay).10

Raffles MS 18, on the other hand, is purportedly based on a version written in Melaka in the late 16th century. Given this, one possibility is that Leyden’s version of the Sejarah Melayu is a later rendition of the Raffles MS 18 version and not earlier as it has been officially documented. The two versions may reflect the different geo-political and cultural concerns of the Melaka Straits region in these two time periods.

Articulation of Charisma and Sovereignty

Sang Nila Utama also plays an important role in establishing sovereignty, though again, both the Raffles MS 18 and Leyden versions portray this differently.

In the Raffles MS 18 version, following Sang Utama’s appointment as ruler of Palembang, a ritual officiator named Bath emerged from the vomit of the cow owned by Wan Empok and Wan Malini, two women who lived on Bukit Seguntang, where Sang Utama and his two brothers had suddenly appeared. Bath proceeded to pronounce Sang Utama’s rule over all of Suvarnabhumi (the Golden Land),11 and bestowed on him the title Sri Tri Buana, which means “Lord of the Three Worlds”.12

While “Sang Utama” – a Malay name containing a prefix title denoting a person of high status – was reflective of sovereignty over a localised sphere (i.e. Palembang), “Sri Tri Buana” – a Buddhist Sanskrit name containing a prefix title denoting a person of high status – symbolises sovereignty over a larger ecumenical sphere.

In the Leyden version, the three young princes, sons of Raja Chulan, appeared on Bukit Seguntang. Of these, only one – Bichitram Shah – proclaimed himself as raja. The two women who lived on Bukit Seguntang gave Bichitram Shah the title Sang Sapurba. The bull on which Bichitram Shah was riding then vomited foam, out of which appeared a man named Bath. Bath then proceeded to recite the praises of Sang Sapurba, and gave him the title Sang Sapurba Trimari Tribhuvena.13

Following this, Demang Lebar Daun, the chief of Palembang, as well as the rajas of the neighbouring countries, came to pay their respects to Sang Sapurba. It was only after Sang Sapurba married the daughter of Demang Lebar Daun did Sang Sapurba become the ruler of Palembang.

Sang Sapurba eventually left with his entourage to establish a new settlement elsewhere. He arrived in Bentan at the invitation of the queen. The queen then chose Sang Nila Utama, the son of Sang Sapurba, to be the husband of her daughter Wan Sri Bini; thereafter Sang Nila Utama became the raja of Bentan.

During a hunting trip one day, Sang Nila Utama noticed the white sands of Temasik in the distance and sailed to visit the island. He decided to form a settlement on Temasik, naming it Singhapura (Singapura)14 and to reign over it. Bath, who had earlier panegyrized over Sang Sapurba and given him the title Sang Sapurba Trimari Tribhuvera, now sang the praises of Sang Nila Utama, the son of Sang Sapurba, and accorded him the title Sri Tri Buana.

Singapore probably received its epithet “Lion City” because the lion was an auspicious symbol of Buddhism practised in 14th-century Southeast Asia. The Sejarah Melayu descriptions of Sri Tri Buana suggest he was consecrated as an incarnation of a Bodhisattva, probably the Amoghapasa form of Avalokitesvara, thereby justifying his claim to rulership over the Malays, who had yet to convert to Islam. As an incarnation of Avalokitesvara, he would have been seated on a lion throne or singhasana – as depicted in this 13th–14th-century Chinese figure, in gilt bronze with silver inlay, of Guanyin, the Chinese form of Avalokitesvara. Collection of the Asian Civilisations Museum.

Singapore probably received its epithet “Lion City” because the lion was an auspicious symbol of Buddhism practised in 14th-century Southeast Asia. The Sejarah Melayu descriptions of Sri Tri Buana suggest he was consecrated as an incarnation of a Bodhisattva, probably the Amoghapasa form of Avalokitesvara, thereby justifying his claim to rulership over the Malays, who had yet to convert to Islam. As an incarnation of Avalokitesvara, he would have been seated on a lion throne or singhasana – as depicted in this 13th–14th-century Chinese figure, in gilt bronze with silver inlay, of Guanyin, the Chinese form of Avalokitesvara. Collection of the Asian Civilisations Museum.

While the two versions of the Sejarah Melayu differ in terms of the details of the narrative, they nonetheless highlight two important functions. First, in both accounts, the panegyrization and declaration of the new name signified an elevation of status, in terms of personal charisma as well as the scope of influence. Following the panegyrization and name declaration, the scope of the individual’s influence extended, both geographically (in terms of world, spheres and states) and also in the number of people who would come to pay him homage (i.e. charisma).15 As such, the name “Sang Nila Utama” is significant in the Sejarah Melayu as it represents the transitional phase in the enhancement of the stature of a person of importance.

Second, the panegyrization and declaration of a new name typically, though not always, heralded the establishment of local authority of a person over an existing territory and its people. In specific situations, such as the founding of Singhapura on Temasik by Sang Nila Utama, it also resulted in a new polity. In this regard, the use of Sang Nila Utama as a character in the Sejarah Melayu is critical in articulating political charisma and sovereignty in the pre-modern Malay world.

The Revisionist History of the Melaka Sultanate

There has been much discussion among scholars about the place of the pre-Melakan period – as narrated in the Sejarah Melayu – in the historiography of the early modern Malay world. The general consensus is that the pre-Melakan account seeks to establish a genealogy for the rulers of the Melaka Sultanate. As a codified oral tradition, the text was intended as a bridge between the historical period, and the pre-historic and semi-mythical stories of the ancient past.

One of the challenges facing the Sejarah Melayu as a historical text is that the historicity of the pre-Melakan era, in which the Singapura period falls, cannot be verified by other sources. In contrast, events during the time of the Melaka Sultanate (which existed from around 1400 to 1511 until it was captured by the Portuguese) may be corroborated by Chinese, European and Middle Eastern texts, a number of which were contemporaneous to the Melakan period. There is just one text, Daoyi zhilue16 (c. 1349), by the 14th-century Chinese traveller Wang Dayuan, which refers to a polity in Singapura. The text mentions a diadem (a type of crown) worn by the ruler of Longyamen (龙牙门; Dragon’s Teeth Strait), which refers to present-day Keppel Harbour.17 The only corroborative evidence thus far has been archaeological, which cannot be tied definitively to the narrative of the Singapura period in the Sejarah Melayu.

Scholars have also attempted to reconcile, in particular, Portuguese accounts of Melaka’s founding with that of the pre-Melakan narrative in the Sejarah Melayu. According to the Suma Oriental18 (c. 1513) by the Portuguese apothecary and chronicler Tomé Pires, a prince of Palembang by the name of Parameswara fled to Temasik after failing to overthrow Javanese overlordship in an uprising and was welcomed by the local ruler there. Parameswara then murdered the ruler and usurped his throne. After a few years as the ruler of Singapura, Paramesara was forced to flee when he received news of an impending Siamese expedition taking revenge for the usurpation. Parameswara fled northwards to Muar and then to Melaka. Following his conversion to Islam, Parameswara changed his name to Iskandar Shah.19

Various scholars have argued that the Parameswara/Iskandar Shah in the Portuguese accounts was likely to have been the Iskandar Shah of the Sejarah Melayu, a fourth-generation direct descendant of Sri Tri Buana, and the fifth and last ruler of Singapura, who fled to Melaka following a successful attack on Temasik by the Javanese.

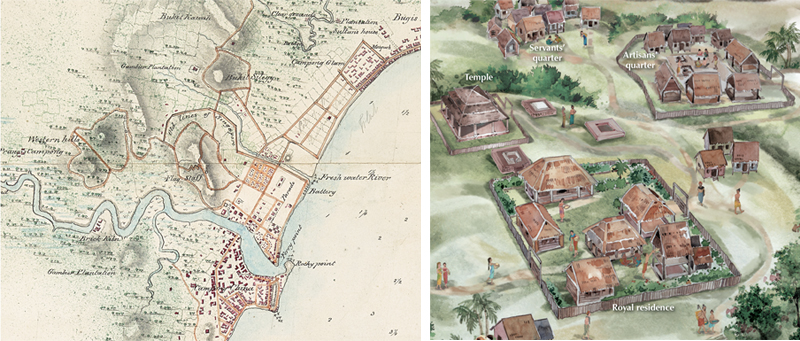

(Left) Detail from “Town & Harbour of Singapore, from Sentosa to Tanjong Rhu”, c. 1823. Several features that may be dated to the Temasik period of Singapore’s history are recorded on this. These include the “Old Lines of Singapore”, denoting the earth rampart, and the “Fresh Water River”, denoting the moat that ran alongside it. © The British Library Board (IOR/X/3346). (Right) An artist’s impression of the Royal Residence, Temple, Servants’ Quarter and Artisans’ Quarter on Fort Canning Hill. In the 14th century, a thriving port-settlement was located in the area comprising the north bank of the Singapore River and Fort Canning Hill. Historical accounts and important archaeological discoveries have shed light on the physical features, economic activities and social nature of this settlement, enabling us to visualise what life in Singapura might have been like seven centuries ago. This is a detail taken from a much bigger illustration showing the reconstruction of Fort Canning Hill. Image reproduced from Kwa, C.G., Heng, D., Borschberg, P., & Tan, T.Y. (2019). Seven Hundred Years: A History of Singapore (p. 30). Singapore: National Library Board and Marshall Cavendish International. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 KWA-[HIS]).

(Left) Detail from “Town & Harbour of Singapore, from Sentosa to Tanjong Rhu”, c. 1823. Several features that may be dated to the Temasik period of Singapore’s history are recorded on this. These include the “Old Lines of Singapore”, denoting the earth rampart, and the “Fresh Water River”, denoting the moat that ran alongside it. © The British Library Board (IOR/X/3346). (Right) An artist’s impression of the Royal Residence, Temple, Servants’ Quarter and Artisans’ Quarter on Fort Canning Hill. In the 14th century, a thriving port-settlement was located in the area comprising the north bank of the Singapore River and Fort Canning Hill. Historical accounts and important archaeological discoveries have shed light on the physical features, economic activities and social nature of this settlement, enabling us to visualise what life in Singapura might have been like seven centuries ago. This is a detail taken from a much bigger illustration showing the reconstruction of Fort Canning Hill. Image reproduced from Kwa, C.G., Heng, D., Borschberg, P., & Tan, T.Y. (2019). Seven Hundred Years: A History of Singapore (p. 30). Singapore: National Library Board and Marshall Cavendish International. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 KWA-[HIS]).

Some scholars have argued that the author of the Sejarah Melayu utilised the Temasik and pre-Temasik narrative to conceal the murder committed by Parameswara and thus erase the bloody event that marked the founding of Melaka. This revisionist account that was composed at the patronage of the Melakan court was also possibly designed to excise the stigma associated with the title Parameswara, which denotes a male consort of a lower rank than that of his royal wife.

As a result, the founder of Melaka and the progenitor of the Melakan royal family had to be elevated to a status that was befitting of a ruler of Singapura who was descended from the divine lineage of Sri Tri Buana. This impeccable genealogy, as mentioned previously, is traced back to the maritime realm of island Southeast Asia, the Hindu sphere of the Chola kingdom, and the Buddhist sphere of the Hellenistic and Gandharan worlds.

In this regard, the framing of Sang Nila Utama as a character in the pre-Melakan period serves as a lynchpin that enables the revisionist insertion of a royal lineage, which was transregional and possessed a high charisma that resounded throughout the entire Malay world. Sang Nila Utama’s story is thus a tool that conferred pedigree, charisma and status upon the rulers of the Melaka Sultanate. This argument has been made by scholars such as Kwa Chong Guan, who notes that Parameswara’s violent act was mythologised into the figure of Sang Nila Utama as early as 1436.20 The new narrative conferred legitimacy through panegyrization, name giving and the conduct of ritual – all of which are centered on the mythical character known as Sang Nila Utama.

As such, although a literary character, Sang Nila Utama played a large and important historiographical role in the region and beyond. He was critical to the primordial, pre-modern and early modern history of the Melaka Sultanate, conferring pedigree, charisma and an extensive sphere of influence on Melakan royalty. Although the account of Singapura’s founding may have been mythical, it had very real historical and political implications in the Malay world of the time.

Dr Derek Heng is Professor and Department Chair in the Department of History, Northern Arizona University. He specialises in the transregional history of maritime Southeast Asia and the South China Sea in the first and early second millennia AD. He is the co-author of Seven Hundred Years: A History of Singapore (2019).

Dr Derek Heng is Professor and Department Chair in the Department of History, Northern Arizona University. He specialises in the transregional history of maritime Southeast Asia and the South China Sea in the first and early second millennia AD. He is the co-author of Seven Hundred Years: A History of Singapore (2019).

REFERENCES

Lin, C. (2019, May 5). HDB unveils plans for new park in Bidadari estate. CNA. Retrieved from Channel NewsAsia website.

National Library Board. (2011). Sang Nila Utama Secondary School written by Chow Yaw Huah. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website.

Ng, M. (2020, January 6). Bidadari HDB estate taking shape as residents move in. The Straits Times. Retrieved from The Straits Times website.

Prime Minister’s Office, Singapore. (2019, November 3). DPM Heng Swee Keat at the grand reunion of the alumnus from Sang Nila Utama Secondary School and Tun Seri Lanang Secondary School. Retrieved from Prime Minister’s Office, Singapore website.

Yuen, S. (2019, November 3). Road in Bidadari estate near former Malay secondary school site to be named Sang Nila Utama Road. The Straits Times. Retrieved from The Straits Times website.

NOTES

-

Sulalat al-Salatin (Genealogy of Kings) is one of the most important works in Malay literature and was likely composed in the 17th century by Bendahara Tun Seri Lanang, the prime minister of the Johor Sultanate. ↩

-

During the reign of Sang Nila Utama’s son, Sri Pikrama Wira, Singapura was strong enough to challenge Majapahit, the major power in the archipelago. This escalated into a major Majapahit invasion of Singapura, which was successfully repelled. Sri Pikrama Wira’s marriage to the daughter of the Tamil ruler of Kalinga illustrates Singapura’s wealth and stature among Indian kingdoms. The Sejarah Melayu also describes the story of the Raja of Kalinga pitting his strongman against Singapura’s reigning champion, Badang, which can be interpreted as a competition for power between the two states. See Kwa, C.G., Heng, D., Borschberg, P., & Tan, T.Y. (2019). Seven hundred years: A history of Singapore (pp. 54–55). Singapore: National Library Board and Marshall Cavendish International. (RSING 959.57 KWA-[HIS]) ↩

-

Leyden, J. (1821). Malay Annals: Translated from the Malay language by the late Dr. John Leyden with an introduction by Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown. Retrieved from BookSG; Winstedt, R.O. (1938, December). The Malay Annals of Sejarah Melayu. Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 16 (3) (132), 1–226. The English translation of Raffles MS 18 may be found in C.C. Brown. (1952, October). The Malay Annals. Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 25 (2 & 3) (159), 5–276. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

John Leyden was a Scottish poet and linguist who spoke several languages, including Malay. Ibrahim Candu, a Tamil-Muslim scribe from Penang was said to have made a copy of the Sejarah Melayu in Jawi which he brought to Calcutta in 1810. Ibrahim explained the text to Leyden who wrote it down. Unfortunately, Leyden died two weeks after arriving in Java in August 1811. After his death, Leyden’s close friend, Stamford Raffles, kept many of his papers, including the Sejarah Melayu. In 1816, Raffles wrote the introduction to Leyden’s English translation of the text, which was published in 1821. ↩

-

Kwa, C.G. (2010). Singapura as a central place in Malay history and identity (p. 135). In K. Delaye, K. Hack & J.L. Margolin (Eds.), Singapore from Temasek to the 21st century. Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 SIN-[HIS]). For a discussion on the provenance of the Leyden version, refer to Hooker, V.M., & Hooker, M.B. (2001). Opening the annals (pp. 31– 51). In V.M. Hooker & M.B. Hooker (Eds.), John Leyden’s Malay Annals. Kuala Lumpur: Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. (Call no.: RSING 959.51 JOH). For a discussion of the various versions and renditions of the Sejarah Melayu, refer to Roolvink, R. (1967). The variant versions of the Malay Annals. Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, 123 (3), 301–324. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

For a more detailed discussion of the history of Singapura and Temasik, refer to chapters one and two in Kwa, et al., 2019. ↩

-

The Hellenistic age refers to the period between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE and the conquest of Egypt by Rome in 30 BCE. Gandhara was an ancient region corresponding to present-day north-west Pakistan and north-east Afghanistan. Gandhara was conquered by Alexander the Great in 327 BCE. ↩

-

The orang laut, which means “sea people” in Malay, refers to the indigenous sea nomads living along the coastlines of Singapore, the Malay Peninsula and the Riau Islands. ↩

-

Hooker & Hooker, 2001, p. 32. ↩

-

Shellabear, W.G. (1896). Sejarah Melayu. Singapore: American Mission Press. (Available via PublicationSG) ↩

-

The Sanskrit term “Suvarnabhumi”, which means “Land of Gold”, is of Indic origin and appears in important Indian texts such as the Hindu Ramayana, the Buddhist Mahavansa and the Jatakas. ↩

-

The three worlds, according to Buddhist cosmology, are the realm of the world of desires of man, the world of form of the Buddha and the world without form or pure perception. See Kwa, 2010, p. 153. ↩

-

Iain Sinclair provides a composite translation of this title as “absolute righteous ruler of the three worlds”. See Sinclair, I. (2019, Mar–May). Sang Sapurba/Maulivarmadeva, First of the last Indo-Malay kings. NSC Highlights, 12, 6–8, p. 7. Retrieved from ISEAS website. ↩

-

Singapura is derived from the Sanskrit words simha, which means “lion”, and pura, which means “city”. ↩

-

Drakard, J. (1990). A Malay frontier: Unity and duality in a Sumatra kingdom (pp. 16–18). Ithaca, NY: Cornell Southeast Asia Program. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Daoyi zhilue (岛夷志略; Description of the Barbarians of the Isles) was written by Wang Dayuan (汪大渊), a traveller from the Yuan dynasty, who recounted his visits and travels to Southeast Asia, South Asia and Africa. The publication describes the people, customs, products, weather and geography of the places he visited. According to Wang, there were two trading settlements on Temasik: Banzu, located on and around Fort Canning Hill, and Longyamen (proposed by historians to have been located at present-day Keppel Straits). See Kwa et al., 2019, pp. 26–27. ↩

-

Wheatley, P. (1966). The golden Khersonese: Studies in the historical geography of the Malay Peninsula before A.D. 1500 (pp. 75–88). Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Press. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.5 WHE) ↩

-

Suma Oriental is the oldest and most extensive account of the Portuguese East at the beginning of the 16th century. Tomé Pires included information on the history, geography, ethnography, and the commerce and trade of not only Melaka but also other countries and port-cities in India, China and the East Indies that he visited. See Kwa et al., 2019, p. 57. ↩

-

Cortesão, A. (1944). The Suma oriental of Tomé Pires: An account of the East, from the Red Sea to Japan, written in Malacca and India in 1512–1515, and The Book of Francisco Rodrigues, rutter of a voyage in the Red Sea, nautical rules, almanach and maps, written and drawn in the East before 1515 (pp. 229–238). London: Hakluyt Society. (Call no.: RRARE 910.8 HAK; Microfilm nos.: NL14208, NL26012) ↩