A Bite of History: Betel Chewing in Singapore

Fiona Lim and Geoffrey Pakiam look at this time-honoured tradition – once a mainstay in Malay, Indian and Peranakan homes – that has since fallen out of fashion.

A sirih seller, Indonesia, late 19th–early 20th centuries. Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

A sirih seller, Indonesia, late 19th–early 20th centuries. Courtesy of National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Betel chewing has been practised for thousands of years in Asia. Across Southeast Asia, betel chewing (makan sirih1 in Malay) was once a social necessity. The practice was also deeply embedded in Indian and Peranakan communities. However, the rich symbolism in the various elements of betel chewing, as well as the important social and cultural functions that it once served, has often been overshadowed by the visual spectacle of the betel chewers, with their black-stained teeth, crimson lips, scarlet saliva and proclivity for spitting.

In Singapore, betel chewing has all but died out among its people today, and the practice is now sustained largely by migrants and visitors from regions where chewing betel remains widespread.

A Millennia-old Asian Habit

Fragments of containers from the 14th century that held lime (calcium carbonate) have been discovered in Singapore, attesting to the likelihood that betel chewing on the island dates from this period at least.2 However, the quid has been part of Asia’s social and cultural landscape for much longer. One of the oldest known sources of evidence dates to around 2660 BCE: skeletal remains with stained teeth suggestive of betel chewing, as well as containers for storing lime, were discovered at a burial site in Duyong Cave on the island of Palawan in southern Philippines.3

Historian Anthony Reid points out the wide-ranging indigenous terms for areca nut and betel used in the Indonesian Archipelago and the Philippines, suggesting that the betel quid originated from island Southeast Asia.4 The areca palm itself (Areca catechu) may have a Malayan origin, judging by the sheer number of palm varieties recorded in the Malay Peninsula.5

The archaeological and linguistic records found in southern India strongly suggest that the areca palm and betel vine (Piper betle) came from Southeast Asia, probably from the second millennium BCE onwards.6 Through centuries of maritime trade and migration, betel chewing and its accompanying botanical material spread throughout Southeast Asia to the western Pacific, across the Indian subcontinent and even reaching as far as the fringes of East Africa.

A painting of two men selling betel quid by an Indian artist, c. 1800s. Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

A painting of two men selling betel quid by an Indian artist, c. 1800s. Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

A Parcel Like No Other

While it is often referred to as betel chewing, strictly speaking, what is chewed is known as the betel quid. In its most basic form, the betel quid comprises three ingredients: betel leaf (sirih), areca nut (pinang) and slaked lime (kapor or chunam), a paste made from the powdered shells of molluscs or coral. Slaked lime is first spread on the leaf before shavings or pieces of dried areca nut are laid on top. The leaf is then folded inwards to cover the contents, ready to be chewed.

The basic elements of the betel quid: the betel leaf (sirih), pieces of areca nut (pinang) and a smear of slaked lime (kapor or chunam), a white paste made from the powdered shells of molluscs or coral. Photo from Shutterstock.

The basic elements of the betel quid: the betel leaf (sirih), pieces of areca nut (pinang) and a smear of slaked lime (kapor or chunam), a white paste made from the powdered shells of molluscs or coral. Photo from Shutterstock.

Preparation techniques varied according to cultural and individual preferences. According to Gwee Thian Lye (better known as G.T. Lye), a well-known dondang sayang7 performer and consultant on Peranakan culture, two types of betel leaves were chewed in Singapore: one larger and dark green, the other smaller and light green. Peranakan Chinese ladies are said to have favoured the latter for making sirih, while the Indian and Malay communities mainly used the former.8

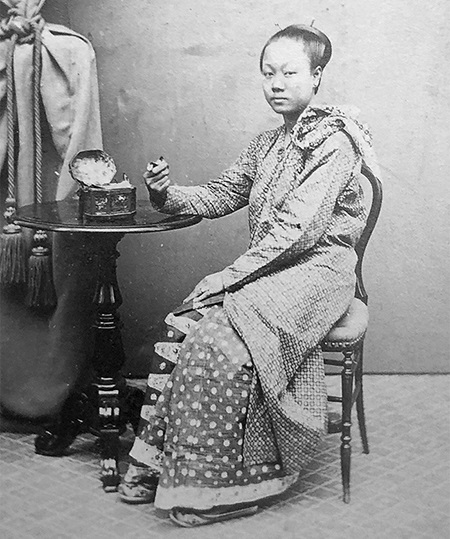

Portrait of a Peranakan Chinese woman holding a betel quid by August Sachtler, Singapore, c. 1860s. On the table is a betel box. Collection of Mr and Mrs Lee Kip Lee. Courtesy of Peter Lee.

Portrait of a Peranakan Chinese woman holding a betel quid by August Sachtler, Singapore, c. 1860s. On the table is a betel box. Collection of Mr and Mrs Lee Kip Lee. Courtesy of Peter Lee.

Many also considered gambier to be an essential ingredient and small pieces would be added alongside the areca nut slices. Later, tobacco became a popular addition and shreds of it might be folded together with the leaf. For a change of flavour, betel chewers sometimes rubbed a wad of tobacco against their teeth and gums after chewing betel.9

Known as vetrilai (Tamil), paan supari (Hindi) or tambula (Sanskrit), the betel quid favoured by Tamils included finely ground spices such as cardamom, clove, nutmeg and mace for an extra dash of fragrance. The mix of spices is known as paan masala and each betel quid vendor (paanwalla) had his own unique mix. A clove might also be used to seal the betel package.

The English herbalist John Gerard first described the areca nut as the “drunken date” in 1597, due to its supposedly intoxicating effects when consumed together with slaked lime.10 The common physiological effects of areca nut, similar to narcotics and stimulants, include a sense of well-being, heightened alertness, increased bodily warmth, improved digestion and better stamina.11 The combination of lime and areca nut releases the latter’s alkaloids, particularly arecoline, producing a sedative effect. At the same time, arecoline affects the peripheral and central nervous systems of the body.12 Chewing the quid also produces copious amounts of red saliva, leading to the habit of frequent spitting and even red stools.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that some 600 million people around the world consume some form of areca nut today. The areca nut is classified as a carcinogen by the WHO, and studies have shown a correlation between betel chewing and cancer of the mouth and esophagus.13

As with other widely consumed alkaloids like caffeine and theobromine (the latter is present in cocoa), the psychotropic effects of betel chewing vary between individuals and, perhaps more importantly, are heavily tempered by social context. Those accustomed to viewing betel chewing as a comforting and calming practice may feel calm and relaxed from chewing, while the habit may have the opposite effect on someone brought up to believe in betel chewing’s stimulating effects.

Our Daily Chew

In Singapore and Malaya during the 19th and early 20th centuries, the betel quid was enjoyed by a broad swathe of society, often transcending class and gender. It was consumed throughout the day, especially after meals due to the quid’s digestive and breath-freshening qualities.14 Although only a minority of Chinese migrants and Eurasians in Singapore appreciated the quid, many aristocrats, merchants and labourers in the Indian, Malay and Peranakan communities chewed betel regularly.15

Perhaps the most fundamental role of the betel quid was in promoting and strengthening social ties.16 Betel chewing served as a social lubricant, like communal eating or drinking alcohol:

“Over a chew of betel, they might cogitate over the day’s problems, or gossip with a neighbour or just sit and relax. Chewing betel is a leisurely business and cannot be hurried over.” 17

During social and business gatherings, it was de rigueur to welcome guests, friends, colleagues and relatives with a tray of betel quid ingredients. According to Reid, “Everyday hospitality consisted in the sharing of betel, not food.”18 Declining the quid was deemed as being disrespectful to the host, and those who did not chew would politely consume a betel leaf at least. The betel set was thus an indispensable part of Tamil, Malay and Straits Chinese homes.19 For some, it was treated like a sacred object that had to be respected. In Straits Chinese homes, placing a betel box on the floor instead of a table when one was seated on a chair was widely believed to invite bad luck.20

As in much of the Malay world, betel chewing in Singapore tended to have feminine overtones. According to a 1951 Singapore Free Press article, among ethnic Indians it was mostly women who “chewed a lot”, and the typical image of a Tamil grandmother in the 1950s was of her “sitting with her legs stretched out at ease and pounding away her chew of betel in her little mortar”.21 Even well into the 1980s, Peranakan Chinese bibik22 were popularly portrayed as deftly folding sirih during card games such as cherki.23 The Malaya Tribune reported in 1949 that many Peranakan Chinese women (known as nonya) were so attached to their chews that “wherever the nonya goes, the sireh set is sure to go”.24 Peranakan Chinese men (baba) who indulged in betel chewing were said to be quite rare, and those who did were perceived to be effeminate.25

However, many men were known to be habitual chewers. Indian labourers sharing areca nuts, betel leaves and lime with one another were once a common sight.26 For them, betel chewing was perhaps a means to stave off hunger and be more alert. Manual workers were said to derive energy from chewing betel during their long hours of work.27 The betel quid was also believed to be particularly useful for those embarking on a long journey, such as Muslims performing the Haj, as it helped tide them over periods of hunger and fatigue.28

A Symbol of Love

The sirih’s centrality in mediating social relations extended to love and romance. The betel quid symbolised courtship, marital and sexual union in Malay, Straits Chinese and Hindu cultures, and features strongly in betrothal rituals. It is believed that the areca nut and betel leaf complement each other perfectly: they are considered “heaty” and “cooling” foods respectively – together they symbolise balance. The betel leaf and areca nut are also said to represent the female and male respectively, alluding to how the betel vine entwines itself around the areca palm.

The age-old association of the betel quid with love and courtship is evident in the etymology of Malay and Tamil words relating to marriage and betrothal. The Malay terms for proposing marriage (meminang) and betrothal (pinangan) are derived from pinang (areca nut), while the Tamil term for engagement, nichaya tambulam, is derived from tambulam (betel quid).

In traditional Malay culture, a suitor or one of his relatives would bring a tray of betel quid to the prospective wife’s residence to ask for her hand in marriage. This custom of hantar sirih (Malay for “presenting betel”) was also practised by the Peranakan community, albeit with some differences. Female guests of a Straits Chinese wedding would have received an invitation known as the sa kapor siray – a miniature triangular parcel of betel quid containing a smidgen of areca nut. This custom was still practised in post-war Singapore, but was replaced by Western-style invitation cards by the 1980s.29 Similarly, the Chetty Melaka (Peranakan Indians) had a ritual known as hantar sirih kovil pathiram during which trays of invitation cards, betel leaves, areca nuts, flowers and other items would be blessed at the temple before being distributed to guests.30 One’s acceptance of a betel quid in most social contexts implied agreement.

In Malay weddings, a ceremonial betel box known as the tepak sirih, containing betel quid ingredients, was once the centrepiece in the bridal display. Traditionally, the tepak sirih was also placed outside the newlyweds’ room on the first night of marriage as an indication of the bride’s chastity. If the groom discovered that his wife was not a virgin, the tepak sirih would be turned upside down the next morning.31 In Straits Chinese culture, the betel box also symbolised the bride’s purity: on the wedding day, a betel box was placed in the centre of the marital bed. These rituals are no longer customary in Singapore as most Malay and Straits Chinese weddings now take on a more contemporary flavour.

However, Malay weddings today still feature the betel leaf in various guises: sirih dara, sirih junjung and sirih lat-lat. Sirih dara and sirih junjung refer to floral arrangements featuring verdant green betel leaves rolled into a conical shape, representing the virginity of the bride and groom respectively. These are displayed during the wedding ceremony.

A Malay wedding sirih set, 2004. It comprises a gold embroidered red container filled with betel leaves, brass receptacles for holding the incense and air mawar (rose water), and a container for storing the areca nut (pinang) and slaked lime (kapor or chunam). PictureSG, National Library, Singapore.

A Malay wedding sirih set, 2004. It comprises a gold embroidered red container filled with betel leaves, brass receptacles for holding the incense and air mawar (rose water), and a container for storing the areca nut (pinang) and slaked lime (kapor or chunam). PictureSG, National Library, Singapore.

Sirih lat-lat is a small floral bouquet containing betel leaves, which is delivered to the groom on the wedding day to signal the bride’s readiness to be visited by the groom and his entourage. According to researcher Khir Johari, the betel leaf, or sirih, generally represents humility, generosity and respectfulness in the Malay world – a reflection of the way in which the betel vine climbs up its host plant unobtrusively.32

The betel quid is considered an aphrodisiac in the Kamasutra, the ancient Sanskrit text on sexuality and eroticism.33 In Hindu marriage ceremonies, trays of betel quid, symbolising everlasting bonds, were passed around for guests to chew.34 Although betel quid ingredients are still used in Hindu prayer offerings and wedding ceremonies today, the quid is rarely chewed.

| THE BETEL CHEWER’S TOOLKIT |

| A typical betel set might comprise a box with three or four containers (cembul) – for storing betel leaves, sliced areca nut, slaked lime, gambier or tobacco – and a slicer (kacip) for cutting the dried areca nut. The quality of a betel caddy indicated the owner’s social status: the working class had their betel chewing paraphernalia wrapped simply in a piece of newspaper or cloth, or kept in a wooden box, while the well-heeled showcased betel boxes made of highly decorated brass, copper or silver.35 Ornate kacip often featured handles carved in the form of the kuda sembrani, the Malay mythological flying horse.36 |

| A moderately wealthy household usually had two betel sets at home: one for daily use and another for guests. The more elaborate betel boxes ended up as family heirlooms or collectors’ items. Alongside betel sets, spittoons were also a common fixture in homes and establishments to hold the red spittle produced from chewing betel. These spittoons were often made of brass or porcelain. Elderly chewers who lacked teeth used a small mortar and pestle to grind larger ingredients, if not the entire quid, into a finer consistency for an easier chew.37 |

| Betel chewing also shaped sartorial practices. A wealthy Malay lady in the 1920s might wear an intricately crafted silver belt from which hung a purse and a case to contain betel ingredients so as to satisfy her craving for a chew while she was out.38 A Straits Chinese woman would drape a large red or dark-coloured handkerchief, folded into a triangle, over one shoulder of her kebaya for wiping red spittle from her lips.39 |

An early 20th-century Straits Chinese betel set comprising four containers (cembul) for storing betel leaves, areca nut slices, slaked lime and gambier, and a nut slicer (kacip) designed as the Malay mythical flying horse known as the kuda sembrani. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board. An early 20th-century Straits Chinese betel set comprising four containers (cembul) for storing betel leaves, areca nut slices, slaked lime and gambier, and a nut slicer (kacip) designed as the Malay mythical flying horse known as the kuda sembrani. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board. |

The Decline of Betel Chewing

By the 1950s, betel chewing had reportedly fallen out of favour among younger adults in Singapore.40 Some 30 years later, the practice was near extinction, enjoyed only by the elderly, a remarkable decline of such an old, pervasive habit within a single generation.

Growing concerns about betel chewing’s long-term effects on health likely played a part in deterring youths from picking up the habit, and perhaps nudged some older people into reducing their chewing frequency. While sirih is a common ingredient in traditional Malay medicine, betel chewing from the 1930s onwards became increasingly associated with oral cancer. The purported dental benefits of chewing betel, such as the strengthening of teeth and gums, were also challenged in popular media. That said, Singapore newspapers continued to run health advisories against betel chewing as late as the 1980s, suggesting that such advice was often ignored, particularly among habitual chewers.

Changing social and cultural attitudes were, perhaps, greater contributing factors to the quid’s demise in Singapore. Once socially acceptable, betel-stained teeth were increasingly perceived as unsightly, thanks to the circulation of images in mass media of “beautiful” people with spotless, gleaming teeth. Negative perceptions were also reinforced by unflattering portrayals of chewers in Asian literature. In a short story published in the Malay-language newspaper Berita Harian in 1964, the protagonist was so repulsed by his wife’s betel-stained teeth that “he wanted to jump from the window”.41 Meanwhile, the effect of red-stained lips caused by betel chewing, often coveted by women as a marker of beauty, was achieved by cosmetics, which replaced the increasingly unfashionable chew. In a 1994 feature in The Straits Times, Helena Rubenstein’s Rouge Glorious lipstick was touted as “a cross between a shine-less matt lipstick and a long-wearing one with cling-to-the-lip colour but without the betel-nut stain effect”.42

The habit was also often deemed unsanitary due to the frequent spitting that accompanied the chewing. When betel chewing was still widespread in Singapore, walkways and roads in the town area were covered in red blotches of spittle, prompting frequent complaints about defaced environments and hygiene issues. One writer expressed disgust at the “revolting scarlet gobs of the betel chewer” that occasionally landed on an unfortunate passer-by.43 Newspapers published numerous letters airing similar grievances up until the 1980s.

Anti-tuberculosis campaigns in the post-war decades also portrayed spitting as socially deviant and disease-spreading. Given the many negative connotations surrounding betel chewing, it was perhaps unsurprising that aspirational individuals and households found it difficult to reconcile the age-old habit with new forms of civic-mindedness and respectability in Singapore.

As independent Singapore pursued its modernisation plans at full throttle, betel chewing became a habit associated with the older generations and was perceived as an outdated practice. In the mid-1970s, the weekend crowd at Geylang Serai Market was described as comprising mostly the elderly who chewed betel together.44 In Little India, too, the main chewers were older proprietors, seated in front of their shops.45 By the late 1980s, the paanwalla was considered part of a long list of vanishing trades in Singapore, along with Indian parrot astrologers and Chinese letter writers.

(Left) A paanwalla, or betel quid vendor, at his stall, 1968. By the 1980s, as betel chewing had fallen out of favour, these vendors, once a ubiquitous sight in Singapore, joined the ranks of a long list of vanishing trades. George W. Porter Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

(Right) A woman with a chew in her mouth, 1955. Betel chewing was a habit indulged in by many women in early Singapore. Donald Moore Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

(Left) A paanwalla, or betel quid vendor, at his stall, 1968. By the 1980s, as betel chewing had fallen out of favour, these vendors, once a ubiquitous sight in Singapore, joined the ranks of a long list of vanishing trades. George W. Porter Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

(Right) A woman with a chew in her mouth, 1955. Betel chewing was a habit indulged in by many women in early Singapore. Donald Moore Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Contemporary Consumption

The 1980s saw the Singapore government vigorously courting the tourist dollar and Little India was developed into a tourist attraction. As a result, the paanwalla were retained and co-opted into the government’s plan to inject “local flavour” into the area.46 In this vision, a guided tour in Little India would not be complete without a visit to the paanwalla for a betel chewing demonstration, where tourists could marvel at his red saliva and stained teeth.47 Betel chewing was thus presented as an object of fascination in a reordered, modern and sanitised city.

The betel quid trade in Singapore today is largely supported by migrants and visitors from countries like Bangladesh, India and Myanmar, where betel chewing remains widespread. A handful of vendors still operate in areas frequented by migrants, such as Little India and Peninsula Plaza. One may also encounter the betel quid in Indian restaurants. Green bundles are strategically placed on trays located near the cashier so that patrons can grab one for a post-meal chew while paying their bill.

In most homes today, betel chewing lives on, if at all, in the memories of those who recall their elderly relatives indulging in the habit:

“I can still see [grandma], fragile and lovely in her sarong kebaya, her bun immaculate even at that hour, each ornate cucuk sanggul in place. Beside her was the betel set that was her trademark, each tiny container holding mystery none of her grandchildren would ever fathom. With each story she delicately prepared and chewed a betel quid, weaving a spell that held us entranced.”48

| The authors would like to thank Gayathrii Nathan and Toffa Abdul Wahed for their research assistance and for reviewing an early draft of the article; Dr Azhar Ibrahim for his thoughts on the subject; and Baba G.T. Lye for participating in the interview. Initial research for this article was conducted for “Culinary Biographies: Charting Singapore’s History Through Cooking and Consumption”, a collaborative project supported by the Heritage Research Grant of the National Heritage Board, Singapore.49 |

Fiona Lim is a freelance writer, editor and researcher. She is interested in the complexities of cities and their people.

Fiona Lim is a freelance writer, editor and researcher. She is interested in the complexities of cities and their people.

Dr Geoffrey Pakiam is a Fellow at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore. He works on the history of commodities and is currently researching the interplay between livelihoods, consumer cultures and the environment of the Malay world.

Dr Geoffrey Pakiam is a Fellow at ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore. He works on the history of commodities and is currently researching the interplay between livelihoods, consumer cultures and the environment of the Malay world.

NOTES

-

Here, sirih refers to the betel quid, but sirih is also the Malay term for the betel leaf. ↩

-

Miksic, J. (2013). Singapore & the Silk Road of the sea, 1300–1800 (p. 316). Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 MIK) ↩

-

Zumbroich, T.J. (2008). The origin and diffusion of betel chewing: A synthesis of evidence from South Asia, Southeast Asia and beyond. eJournal of Indian Medicine, 1 (3), 87–140, p. 99. Retrieved from University of Groningen Press website. ↩

-

Reid, A. (1985, May). From betel-chewing to tobacco-smoking in Indonesia. Journal of Asian Studies, 44 (3), 529–547, pp. 529–530. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Raghavan, V., & Baruah, H.K. (1958). Arecanut: India’s popular masticatory: History, chemistry and utilization. Economic Botany, 12 (4), 315–345, pp. 317–318. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Betel chewing arrived in northern India later, around 500 BCE. See Zumbroich, 2008, pp. 114, 119. ↩

-

Dondang sayang is a traditional poetic art form associated with the Malay and Straits Chinese communities in Singapore and Malaysia. See National Library Board. (2015, March 9). Dondang sayang written by Stephanie Ho. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website. ↩

-

Personal interview with G.T. Lye @ Gwee Thian Lye, 13 June 2020. ↩

-

Mardiana Abu Bakar. (1987, October 12). The betel leaf and its role in Malay life. The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Rohel, J. (2017). Empire and the reordering of edibility: Deconstructing betel quid through metropolitan discourses of intoxication. Global Food History, 3 (2), 150–170, p. 156. Retrieved from Taylor & Francis Group website. ↩

-

Zumbroich, 2008, p. 90. ↩

-

Reid, May 1985, pp. 529–530. ↩

-

How dangerous is betel nut? (2014, October 10). Retrieved from Healthline website. ↩

-

Wee, A. (1987, January 29). Misinformation on Little India. The Straits Times, p. 11; Wee, A. (1987, April 7). Trainee guides get tips on Little India. The Straits Times, p. 15; To Mecca. (1912, September 13). The Singapore Free Press, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Neither the betel quid nor its respective ingredients were particularly significant in the cultures of the Chinese and Eurasians in Singapore. Goh, B.-L. (2018). Modern dreams: An inquiry into power, cultural production, and the cityscape in contemporary urban Penang, Malaysia (p. 131). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University. (Call no.: RSEA 307.76095951 GOH); Choo, C., et al. (2007). Being Eurasian (p. 109). In M. Perkins (Ed.), Visibly different: Face, place and race in Australia. Switzerland: Peter Lang Verlag. (Not available in NLB holdings); Nirmala, M. (2003, July 4). All are welcome at new Eurasian House. The Straits Times, p. 27. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Zumbroich, 2008, p. 90. ↩

-

Ponnudurai, V.R. (1951, August 25). Chewing the betel. The Singapore Free Press, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Reid, A. (1988). Southeast Asia in the age of commerce 1450–1680 (Vol. 1, p. 41). New Haven; London: Yale University Press. (Call no.: RSEA 959 REI) ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press, 25 Aug 1951, p. 9. ↩

-

Personal interview with G.T. Lye @ Gwee Thian Lye, 13 June 2020. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press, 25 Aug 1951, p. 9. ↩

-

A form of address for elderly Peranakan Chinese women. ↩

-

Grand dames bring life to the museum. (1987, September 6). The Straits Times, p. 19. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lee, L.H. (1949, July 8). Keeping on the right side of all the gods. The Malaya Tribune, p. V. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Gwee, T.H. (2013). A nyonya mosaic: Memoirs of a Peranakan childhood (p. 60). Singapore: Marshall Cavendish. (Call no.: RSING 959.57030922 GWE) ↩

-

8,000 labourers on strike in Singapore. (1936, December 2). The Singapore Free Press, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Orme, W.B. (1914, February 7). Makan sireh. The British Medical Journal, 1 (2771), 325–326, p. 326. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press, 13 Sep 1912, p. 3; Reid, 1988, p. 43. ↩

-

Neo, D., & Rathabai, J. (2015). Elaborate customs and rituals. The Peranakan, (2), p. 16. Retrieved from The Peranakan Association Singapore website. ↩

-

Norhuda Salleh. (2015). Tepak sireh: Interpretation and perception in Malay wedding customs. INTCESS15 – 2nd International Conference on Education and Social Services (pp. 1185–1186). Retrieved from International Organisation Center of Academic Research website. ↩

-

Warisan SG. (2015). Sacred sirih: Traditions and symbolism in the Malay world Part 1 [Video]. Retrieved from YouTube. ↩

-

Menon, V. (1981, November 20). The betel and its role in Hindu functions. The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press, 25 Aug 1951, p. 9. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press, 25 Aug 1951, p. 9. ↩

-

Norhuda Salleh, 2015, p. 1184. ↩

-

Chia, F. (1994). The Babas revisited (p. 102). Singapore: Heinemann Asia. (Call no.: RSING 309.895105957 CHI) ↩

-

Hunt for ethnic costumes. (1993, January 19). The Straits Times, p. 19. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The wispy see-through kebaya tantalised many a Baba youth… (1976, May 12). New Nation, pp. 10–11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Singapore Free Press, 15 Aug 1951, p. 9; Betel nuts? We’ll stick to lipstick, say women. (1952, July 30). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Text is translated from Malay. Abdullah Othman. (1964, December 31). Ada jua yang tiada. Berita Harian, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Smooth operators. (1994, July 7). The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Peet, G. (1977, April 2). An old timer on the five-foot-way. The Straits Times, p. 14. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Holmberg, J. (1975, February 1). The old ‘new market’. New Nation, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tan, F. (1975, May 17). Teck Kah… or the place under the bamboo. New Nation, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Hole-in-the-wall stores at Little India to stay. (1992, June 11). The Straits Times, p. 40. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lim, J., & Lim, Y.L. (2012, November 3). Enjoy the city’s charms. The Straits Times, p. 3; Lim, S.N. (1989, April 5). Giving old attractions new life. The Business Times, p. 10; Ng, I., & Fernandez, W. (1987, August 13). Arab Street and Little India captivate tourists. The Straits Times, p. 16. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Juita. N. (1989, May 10). Remembering the childhood joys of past Hari Rayas. The Straits Times, p. 20. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. [Sarong kebaya is the outfit worn by Malay and Peranakan women, comprising a sheer fabric blouse paired with a batik sarong skirt. Cucuk sanggul is a hair pin for securing the bun.] ↩

-

Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Heritage Board, Singapore. ↩