The Borobudur, Mysterious Gold Plates and Singing Maps

Unsolved historical puzzles from Southeast Asia are key elements of the recently published thriller The Java Enigma by debut novelist Erni Salleh.

Sunrise as seen from the summit of Borobudur, with Mount Merapi in the horizon, 2017. Photo by Erni Salleh.

Sunrise as seen from the summit of Borobudur, with Mount Merapi in the horizon, 2017. Photo by Erni Salleh.

Watching the sun rise from Borobudur is a magnificent experience.

The climb to the summit starts at 4 am. As your eyes become accustomed to the darkness, you might spot offerings of flowers and incense at the base of the 9th-century Buddhist monument as the call of prayers from the nearby village mosques serenades your ascent.

When you reach the top, you are greeted by a large central stupa, surrounded by 72 smaller ones. Two of these are exposed, showing a seated Buddha in a lotus pose, one facing the east and the other, west. I like to think these statues are privy to the many secrets still waiting to be uncovered in the region – mysteries and forgotten histories that inspire writers such as myself to speculate and to weave stories around them.

Inspiration for The Java Enigma

It was during such a climb in July 2017 that the inspiration for my novel, The Java Enigma, took root. Just like Irin, the main character of the story, I had received devastating news of my father’s passing while I was away from home. In my case, I was neck-deep in field research at the Borobudur Archaeological Park in Central Java for my post-graduate degree in Southeast Asian Studies, and it was impossible for me to get home in time for his funeral. (Muslim tradition mandates that the deceased be buried within 24 hours of a person’s passing.)

Librarian and debut novelist Erni Salleh. Courtesy of Epigram Books.

Librarian and debut novelist Erni Salleh. Courtesy of Epigram Books.

However, unlike Irin, my late father did not leave me a secret safe deposit box with codes that sent me chasing for clues around the world. Instead, his passing prompted me to dig into his past and his work on marine salvage projects overseas. It brought to memory his adventures navigating treacherous waters and uncovering priceless treasures around the world, from the Java Sea all the way to the Gulf of Mexico. This man, who always seemed larger than life to me, provided the inspiration as well as the starting point for many of the mysteries the reader encounters in my book.

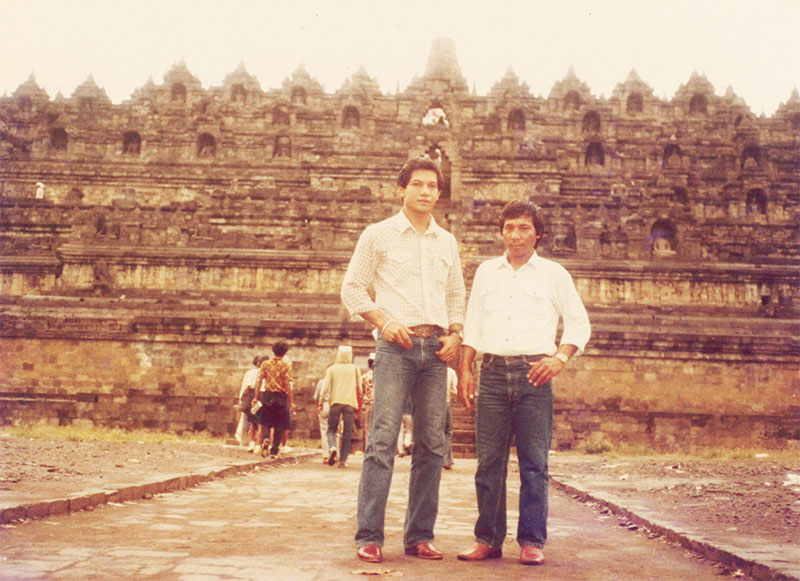

As a librarian, access to this wealth of knowledge felt like being immersed in my own personal archive. I spent hours cataloguing items from my father’s past, piecing together the where, the when and the why. I found some of his earliest moments as a salvage diver captured in photos and discovered that he, too, had spent time at Borobudur.

The writer’s father Mohd Salleh (left) posing with a friend in front of Borobudur a few days before a dive, 1982. Courtesy of Erni Salleh.

The writer’s father Mohd Salleh (left) posing with a friend in front of Borobudur a few days before a dive, 1982. Courtesy of Erni Salleh.

In October 2018, when I had to write a paper on tangible and intangible heritage for my postgraduate course, Borobudur was the natural choice. I visited numerous other temples, as well as plantations and local homestays, and spoke to countless locals and tourists. Returning to Borobudor was cathartic, bringing me closure but also continuity.

In January 2019, armed with research materials about Borobudur and my father’s adventures, I began writing The Java Enigma, which I completed seven months later.

The Java Enigma is a thriller centred around the origins of Borobudur. Irin, the novel’s main protagonist, is a librarian who uncovers the real reason for the hidden panels – known as the Karmawibhangga Reliefs and chanced upon in 1885 – at the base of what is said to be the biggest Buddhist temple in the world. The discovery pits her against those fighting to guard its ancient secrets.

The Research Process

Back in Singapore, I relied heavily on reference materials at the regional libraries and the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library. I also consulted scholarly journals via the library’s access to JSTOR, a digital library of academic journals and books. Not many people know this but reference books at Jurong, Woodlands and Tampines regional libraries can be borrowed, a blessing for time-strapped professionals like me. However, my all-time favourite resource was BookSG – a repository of digitised books and other print materials – because of its amazing collection of digital maps that includes items from The British Library.

All these resources are equally available to the public. My access to rare documents at the National Library was the same as any other library user. Even though I work for the library, I did not get preferential treatment (in fact, I got a minor dressing-down once when I mistakenly brought a pen instead of a pencil into the reading room).

The Writer’s Challenge

My job as a librarian requires me to approach information as a science, classifying and packaging it to meet the needs of users; impartiality being the primary guiding principle. Although my training in history requires me to make inferences, historians are also preoccupied with facts. As a writer of fiction though, I have to distill the essence of my research into an interesting narrative that moves the plot along. This is sometimes at odds with the librarian-historian in me who wants to ensure that the facts are accurate.

How did I resolve this conundrum? I’d like to think that I see information as a piece of a larger puzzle. The librarian in me presents these pieces, the historian connects them, while the writer creates new ones to add on to or disrupt our understanding of that puzzle. The challenge is to know when to hold back one impulse and to let the other have the limelight. You wouldn’t believe the number of times my editor had to remind me that I wasn’t writing a thesis.

I found that immersing myself in fiction was one of the best ways to unleash my fun, creative side. My job with Molly, the mobile library bus, was also good training as it gave me the chance to read with, and read to, children and parents on board the bus. My genre of choice: wordless picture books. You can change the story to suit any audience and make up your own plot along the way – what better way to practise the art of developing a narrative?

Bridging the Historical Gap with Fiction

It is perhaps not surprising that the daughter of a salvage diver would find joy in uncovering the hidden. And the history of the region has no shortage of hidden or unknown aspects. Doing my Masters in Southeast Asian studies opened my eyes to the many gaps in scholarship in this area: narratives lost over the centuries due to the death of ancient languages and ancient cultures, and from perishable records. I used some of these as plot devices in The Java Enigma, from lost 15th-century indigenous maps to the mysterious location of the shipwreck of the Portuguese carrack Flor de la Mar and, of course, the raison d’être of the book’s namesake – the biggest enigma on the island of Java – Borobudur.

Borobudur is the only surviving monument of its kind in Java and, possibly, Southeast Asia.1 In ancient times, a pilgrim would make his way up to the summit, meditating and praying as he circumambulates 10 rounds past the 1,460 relief panels centering around the themes of punishment and reward, the life of Buddha and the search for the ultimate wisdom – symbolic of the 10 stages of existence that a bodhisattva goes through to attain enlightenment.

What a pilgrim today would not see, however, is an additional 160 panels at the base of the monument showing scenes of heaven and hell from Buddhist mythology, illustrating the rewards or punishment of one’s actions. These were concealed by stone slabs at some point, then discovered by accident in 1885 and were covered up again five years later after photographic records were made. What is visible now are four panels in the southeastern corner of the monument, exposed by curious members of the Japanese occupation forces in the early 1940s.

The four previously hidden panels located at the base of the southeastern corner of Borobudur, 2017. Photo by Erni Salleh.

The four previously hidden panels located at the base of the southeastern corner of Borobudur, 2017. Photo by Erni Salleh.

Why were these panels hidden? When was this done and under whose instruction?

Conservationists generally agree that the panels were erected to shore up the sagging stones and provide a broader base to hold up the weight of the upper levels. The lack of a cornice to prevent rain damage or a plinth for added support has led some scholars to believe that “the stone covering had already been foreseen before the whole project was executed”.2 (The reliefs on the other levels of Borobudur have cornices to protect them from the rain.) Of course, the writer of a thriller might have entirely different ideas about why someone would want these panels covered up, and this is why these hidden panels form a major plot element in my book.

One real-life mystery I use for my novel is a set of inscriptions carved into 11 rectangular gold plates that mysteriously appeared at Jakarta’s Museum Nasional Indonesia in 1946. The provenance of these plates and how they suddenly came to be at the museum are an unsolved puzzle to this day. The engravings were copied between 650 and 800 CE from a much earlier scripture that reached Java in the early 5th century. The plates contain well-known Buddhist teachings about the 12 causes of suffering and how to break this chain to attain enlightenment. It was written in a language that transitions between the sacred Pallava script and that of vernacular Old Javanese, or Kawi.3 Bereft of complicated grammatical sentences, the text seems to have been written for commoners rather than for priests or the ruling class.

The most intriguing aspect of these gold plates is the presence of a particular verse that does not have an equivalent in any Buddhist text, whether in the original Indic languages, or in Tibetan or Chinese translations. Yet, this same verse is echoed in artefacts found at eight other locations in Southeast Asia, including three stone slabs discovered in Peninsular Malaysia, and stone stupas in Brunei, Sarawak and Kalimantan. The text reads:

“Ajñānāc cīyate karma janmanaḥ

karma kāraṇam

Jñānān na kritate karma

karmmābhāvān na jāyate.”

(Translation: Through ignorance, karma is accumulated; Karma is the cause of rebirth. Through wisdom, karma is not accumulated; In the absence of karma, one is not reborn.)4

Because this verse is not found in the Buddhist canon, researchers have suggested the possibility of it originating from a local text that was circulated in the region but then was later redacted. This prompts further questions: who selected this verse and chose to associate it with the various artefacts in Southeast Asia? And who sponsored the valuable Javanese gold plates?

What we do know is that the gold plates had likely “served as relics – inscribed to constitute a deposit in a religious foundation such as a stupa” or “one of the large Buddhist temples in Indonesia”.5 But seeing that the origins of the verse are unknown, a writer has the luxury to speculate if it could link to Borobudur. And so the mysterious local text ended up as grist for my literary mill.

Making Sense of Ancient Maps

The artefacts carrying the mysterious verses were discovered at nodal points along the maritime trade routes from India to China. However, this is not to suggest that the verses moved in a single direction, seeing that trade routes are complex and multidirectional, and texts are open to indigenous interpretations and circulation. Glimpses of Southeast Asian mariners – along with their technology of shipbuilding, navigation and cartography – have been preserved in Borobudur’s stone reliefs, which prompted me to make an unexplored connection between sea travels, the origins of Borobudur’s architecture and the meaning behind the untraceable verses.

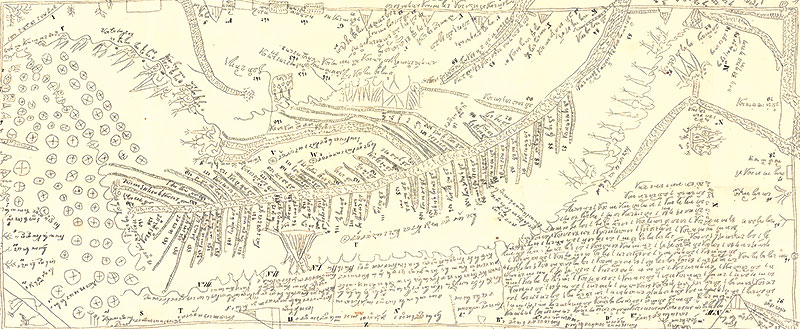

The researcher and curator Thomas Suárez notes that “[i]n early Southeast Asia, there was no absolute distinction between the physical, the metaphysical and the religious. Southeast Asian geographic thought, like Southeast Asian life, could be at once, both empirical and transcendental”.6

This fluidity in time and space is an element I have incorporated into my novel as a way to remind readers to situate their appreciation of these histories and mysteries outside of familiar Western modes of measurements and methods of mapmaking. This is an important consideration so that we don’t see the limited number of extant Southeast Asian maps as inaccurate or having no practical value simply because we are viewing it through the lens of current cartographic conventions.

In his letter to King Manuel of Portugal dated 1 April 1512, Alfonso de Albuquerque, founder of Portugal’s empire in Southeast Asia, wrote that the Bugis of Sulawesi and the maritime traders in Java and Sumatra have been recorded as having maps so detailed that they contained references to “the Clove islands, the navigation of the Chinese and the Gores [people of Formosa], with their rhumbs and direct routes followed by the ships, and the hinterland, and how the kingdoms border on each other”.7

However, the Bugis also relied on unwritten itineraries that were committed to memory in the form of songs so that navigators could construct a mental image of time and space, topography and even landmarks. This might have been the preferred mode of mapmaking by the Bugis, in an attempt to keep their navigational aids confidential, after witnessing “the aggressive commercial spirit of their European visitors”.8 Many of their physical maps, like the one described earlier, ended up in the hands of Europeans or were lost at sea. One such map went missing when the Flor de la Mar sank during its voyage from Melaka to Portugal in 1511. While a copy of this map might have survived thanks to the efforts of Portuguese pilot Francisco Rodrigues in 1513, any mention of European reliance on native Southeast Asian maps seem to have disappeared from written records from this point on.

Detail from a 16th-century map of a district in West Java. This detailed map is drawn in ink on cloth and shows what indigenous mapmaking in Java looks like. Image reproduced from Holle, K.F. (1876). De Kaart van Tjiela of Timbanganten. Tijdschrift voor Indische Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, Deel 24. Batavia: Lange & Co.

Detail from a 16th-century map of a district in West Java. This detailed map is drawn in ink on cloth and shows what indigenous mapmaking in Java looks like. Image reproduced from Holle, K.F. (1876). De Kaart van Tjiela of Timbanganten. Tijdschrift voor Indische Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, Deel 24. Batavia: Lange & Co.

Historical Mysteries or Forgotten Narratives?

The loss of a large corpus of indigenous maps was not as disconcerting as my realisation that despite being a seaman’s daughter, I have never once heard a “map” being sung to me. Surely such a map exists out there, waiting to be documented, if it hasn’t already disappeared from our cultural consciousness? Who’s to say that these lost maps do not provide clues to the secrets and mysteries in the region that remain unsolved today?

As an academic and a writer, I feel the responsibility of bringing to the fore unknown stories that have not made their presence in history books; the literary space being a safe place to explore and present these narratives. The Java Enigma is my attempt at addressing these forgotten histories while bringing the mysteries of our region into a meaningful dialogue with one another. At the same time, to me, the real challenge of using history in fiction is whether in the end you’ve been able to guide your readers to engage with your story emotionally and cognitively, letting them ask their own questions and make their own decisions about the “what-ifs” of our pasts.

The Java Enigma is available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries (Call nos.: RSING S823 ERN and ERN). It also retails at major bookshops in Singapore.

The Java Enigma is available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries (Call nos.: RSING S823 ERN and ERN). It also retails at major bookshops in Singapore.

Erni Salleh is a trained librarian who currently manages the Mobile Library Services at the National Library Board. She is the author of The Java Enigma, which was shortlisted for the 2020 Epigram Book Fiction Prize. An avid traveller, she collects bits of the past – from 19th-century Laotian ceremonial scrolls to generations-old keris from Yogyakarta.

Erni Salleh is a trained librarian who currently manages the Mobile Library Services at the National Library Board. She is the author of The Java Enigma, which was shortlisted for the 2020 Epigram Book Fiction Prize. An avid traveller, she collects bits of the past – from 19th-century Laotian ceremonial scrolls to generations-old keris from Yogyakarta.

NOTES

-

Most ancient Javanese or Buddhist temples have rooms designed to house special objects of worship. Only priests were allowed to enter. Conversely, Borobudur is not intended as a devotional monument to Buddha but a place for pilgrims to achieve enlightenment. ↩

-

Stutterheim, W.F. (1956). Studies in Indonesian archaeology (p. 33). The Hague: M.Nijhoff. (Call no.: RCLOS 992.2 STU). [A plinth is a pedestal or support for a statue or a column in architecture.] ↩

-

The Pallava script is a Brahmic script named after the Pallava dynasty (275 CE to 897 CE) of Southern India. It later influenced the development of languages in Southeast Asia such as Cham (spoken in Cambodia and Vietnam) and Kawi (Old Javanese). Pallava was likely spoken by the religious and ruling classes at the time. ↩

-

Skilling, P. (2015). An untraced Buddhist verse inscription from Peninsular Southeast Asia (p. 33). In D.C. Lammerts (Ed.), Buddhist dynamics in premodern and early modern Southeast Asia. Singapore: ISEAS Publishing. (Call no.: RSEA 294.30959 BUD) ↩

-

De Casparis, J.G. (1956). Selected Inscriptions from the 7th to the 9th century A.D. (pp. 48, 52, 55–56) Bandung: Masa Baru. (Call no.: RU 499.2017 CAS) ↩

-

Suárez, T. (1999). Early mapping of Southeast Asia: The epic story of seafarers, adventurers, and cartographers who first mapped the regions between China and India (p. 27). Hong Kong: Periplus Editions. (Call no.: RSING q912.59 SUA) ↩

-

Suárez, 1999, p. 39. Albuquerque was a military genius and a great naval commander who helped to build and expand the Portuguese Empire. He conquered Ormuz in 1507, Goa in 1510 and Melaka in 1511. ↩