A Different Sky: The Other Side of the Looking Glass

Meira Chand recounts how hours of listening to oral history interviews permeated her subconscious and created a memory that she could call her own when writing her novel.

It has been said the past is a foreign country. Yet, like all remote places, it is possible to travel there if transportation is available. Historical fiction is the conveyance we can use to journey back in time to understand another era. It is a genre of literature that carries the reader on a journey of experience, one that expands our empathy for others and reaffirms our common humanity. It leads us into lives and cultures we might otherwise not know, or into emotional situations we might never face in our own lives.

In this respect, the historical novel is no different from any novel, except it is furnished by actual events of the past. Historical truth rests not only upon recorded facts, but also upon our imaginative understanding of those facts. Accordingly, the value of historical fiction lies in its ability to bring to life for the reader what was thought dead. As a conduit across time, its power to help us understand the past is undeniable.

Borrowing From History

Admittedly, history written in the form of the historical novel can only be viewed as unofficial history. This is why the genre is an area of contention for many academics, its value continually debated and its worth often demeaned by formal historians.

Part of the contention arises because, at the nexus of history and fiction, historians and novelists share common ground, often relying on the same sources. This can produce friction, as seen in the public debate in 2006 between Australian historian Inga Clendinnen, who deplores the free use of factual history by novelists, and the writer Kate Grenville, whose best selling novel, The Secret River, recreates the life and choices of early Australian settlers.1

As the writer of several historical novels myself, I freely admit that I regard history as a story bank to pillage – a place to carry out a smash-and-grab raid and run off with the spoils – albeit done with integrity. All historical novelists regard the rewriting of history within the fictional framework as a legitimate exercise. The fundamental nature of the historical novel is to unlock the past to the present.

Meira Chand is an award-winning novelist of Swiss-Indian parentage. She is now a Singaporean citizen.

Meira Chand is an award-winning novelist of Swiss-Indian parentage. She is now a Singaporean citizen.

Historical fiction is also a form of literary archaeology. The writer journeys to a site, examines its remains and reconstructs the world that these remains imply. The writer must rely upon the images found in these sites, often remoulding them and even adding to them, to produce a creative picture of the past, to understand it anew, and possibly even change our relationship with it. The historical novel is a place between fact and fantasy into which the novelist slips, to seed characters and embody them against a historical backdrop, with the timeless details of our human life journey.

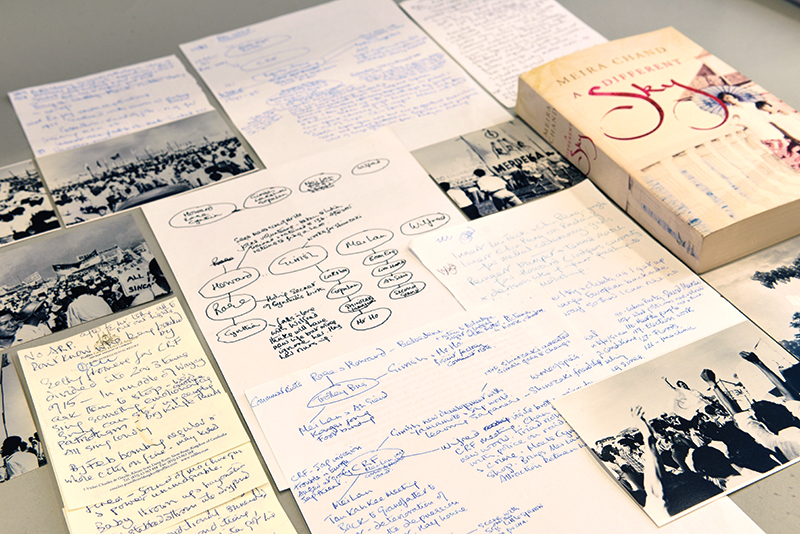

In preparation for writing her book, A Different Sky, Meira Chand conducted extensive research. She subsequently donated her research materials to the National Library. These include notes written on hotel stationery, character sketches, photographs ordered from the National Archives and printouts of emails. The donation also includes a full draft of her novel that she had printed out.

In preparation for writing her book, A Different Sky, Meira Chand conducted extensive research. She subsequently donated her research materials to the National Library. These include notes written on hotel stationery, character sketches, photographs ordered from the National Archives and printouts of emails. The donation also includes a full draft of her novel that she had printed out.

Academic history texts provide important information, for example dates and details of events, how many soldiers were in an army, how many people died in a flood, or the price of bread and cabbages 200 years ago. Only fiction can create a sense of experience, describing the grief of a family when a flood sweeps away a child, or the terror of a soldier as the enemy charges. Historical fiction not only brings the past alive, it illuminates our shared humanity, showing us that our ancestors were little different from ourselves.

If historical fiction is somewhat problematic for some readers, I speak from experience when I say its creation is no less challenging for the writer. After writing his classic War and Peace, Leo Tolstoy declared that the subject of history is the life of peoples and of humanity. It would seem that Tolstoy saw the common people – attending to their everyday lives and unaware of great events – as furthering the unconscious motions of history, rather than the Genghis Khans and Napoleons who only appear to control historical forces.

Tolstoy knew it is the job of fiction to reveal the uncommonness in each common life, and this is a point the writer of historical fiction must always keep in mind. If historical facts are elevated above the characters’ lives in a novel, then there is the danger that the finished work will read like a history book, rather than a novel that illuminates history through the lives and emotions of its characters.

Drawing the Line Between Fiction and Fact

History would seem to provide a ready-made story that the inventive novelist need only write up through the imagined lives of make-believe characters. In reality, the task is quite the opposite: fiction creates a parallel world, and all the facts and emotions in that alternate reality must correspond exactly to the real world, otherwise the work will not carry conviction for either the writer or the reader.

This authenticity is particularly important in the writing of historical narratives. Historical facts must be scrupulously heeded, not only in the matter of dates and events, but in the small details of living and dressing, manners and speech and more; the flavour and colour of a past world must be faithfully and correctly created.

It is at this crossroad of fact and fiction that the writer’s problem is found. Facts are dry and unmovable things and can weigh as heavy as concrete upon the volatile essence that is the imagination. Facts work to tether the imagination, while the imagination, ever restless, agitates to soar free into fantasy.

The imagination does not listen to the rules and principles devised in the writer’s head and written up in ordered plans; it is bold and free, obeying only itself. This liberty of the imagination is a writer’s most precious possession. Through it, a book once underway, will usually take on a life of its own. It will demand that the writer puts in situations, characters and complications never anticipated earlier. The dry historical facts of research, waiting to be incorporated in the developing fiction, do not take kindly to the writer’s cavalier imagination.

If a novel fails to take flight, if the imagination is cramped, the finished work will reflect this loss and will be without flow or vitality. In the course of writing, the world the writer creates, like the other side of the looking glass, produces a logic that is entirely its own, and this logic must be unhesitatingly embraced.

The Problem of Memory

There is a further challenge confronting the writer of historical fiction – that of memory. All writers write from a place of memory, whether personal, national, or a greater collective or archetypal memory. We are all surrounded by our own lives and personal memories, of where we were born, and where we have travelled to, both geographically and emotionally.

However, with the historical novel, the issue of memory presents a special problem because, in most instances, the writer usually lacks a personal memory of the period being written about. In my own historical novels, this problem of memory has always been present. My novel, A Different Sky, set against the backdrop of modern Singapore between 1927 and 1957, is a good example of the challenges that beset the historical novelist.

When I began my research for A Different Sky in 2002, I was relatively new to Singapore and was still learning about the country, its people and history, and its ethnic mix of cultures and communities. I began my research through history books, old newspapers, personal interviews, archival material, memoirs, fiction and anything else I could find.

One marvellous and constant resource was the Oral History Centre of the National Archives of Singapore. There, in hundreds of interviews, a cross section of every community in Singapore has been recorded. There were transcripts of these oral interviews which were, of course, very useful. But most of all, I liked to put on the headphones, play the tapes and hear the multiple voices of diverse peoples and their colourful stories coming at me, working through me.

As I collected more material, other problems began to emerge. To absorb the atmosphere of the times I was writing about, I visited various locations important in the past, only to discover that landmarks of the era had all but disappeared, razed by the building of modern Singapore.

Sago Lane in Chinatown – once a street of funeral parlours, undertakers and death houses – is today a narrow alley between high-rise HDB flats on one side and a construction site on another. Yet, in the period I was writing about, it was thick with the traffic of the bereaved, itinerant hawkers and keening women. Food stalls and confectioners would have catered to the never-ending wakes on the street, and the aroma of burnt sugar and roasting pork would have mixed with the perfume of incense. My description of this long-ago place in A Different Sky had to be found from old photographs, the odd depiction in an old book, and my imagination of course.

Mahjong players outside a death house on Sago Lane, 1962. The road is named after the sago factories located in the area in the 1840s. Sago Lane was also known for its Chinese death houses. Poor Chinese migrants facing imminent death would live out their final days on the upper floor. The lower floors of these houses functioned as funeral parlours. Meira Chand relied on old photographs, old books and her imagination for a description of the road in her novel, A Different Sky. Photo by Wong Ken Foo (K.F. Wong). Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Mahjong players outside a death house on Sago Lane, 1962. The road is named after the sago factories located in the area in the 1840s. Sago Lane was also known for its Chinese death houses. Poor Chinese migrants facing imminent death would live out their final days on the upper floor. The lower floors of these houses functioned as funeral parlours. Meira Chand relied on old photographs, old books and her imagination for a description of the road in her novel, A Different Sky. Photo by Wong Ken Foo (K.F. Wong). Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Another problem was that the amount of material to be considered for inclusion in the book was overwhelming. It was difficult to know what historical events to put into the novel and what to leave out, and still remain true to the historical thread of the narrative. I am not a trained researcher; my methods are thoroughly disorganised, but in an organised way that only I understand. I have never used an assistant, but have to absorb my research personally, quietly, by a strange kind of osmosis. I hold a lot in my head, making strange connections. The details I pick upon to enlarge might appear irrelevant to everyone but they hold illuminating insights for me. Often, the things I see directly before me are less interesting than the things I see out of the corner of my eye. As I read dry history books, I am always hoping to stumble upon comments or incidents that will give life to my novel.

Such morsels are more easily found in memoirs than in history books. One such work, Singapore Patrol, written by an English detective employed by the colonial Singapore police force in the 1920s, helped me find an entry point into A Different Sky.2

Detective Alec Dixon had observed Singapore’s first communist riot in 1927 and, in a few brief sentences in his memoir, described where the mob had come from and how they had rocked a trolley bus with the terrified passengers inside. After reading about the incident – given no more than passing references in history books – it stuck obstinately in my mind until I decided to use the incident. Or, more correctly, the incident decided to use me.

In her novel A Different Sky, Meira Chand references a communist riot taking place around a trolley bus in 1927. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

In her novel A Different Sky, Meira Chand references a communist riot taking place around a trolley bus in 1927. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

I had spent many months trying to find my way into my new book. Even when I had written almost 200 pages, the novel did not feel right. I repeatedly reworked my manuscript, but nothing seemed to help. I started with an Indian character. I started with a Chinese character. I worked with characters that now do not even appear in the book, and events that were subsequently edited out of the story. Eventually, I realised I had fallen into a trap – I was so weighed down by historical facts that I was writing a history book, and the living breathing novel I wished to write was buried beneath all that minutiae. I had been so exacting about the presentation of facts that my imagination had become imprisoned in a dark basement. In despair, I gave up and decided I could not write this book.

The problems I faced so acutely in A Different Sky were largely derived from having no inner memory of the place I was writing about – a problem that has also troubled me in varying degrees in my previous works of historical fiction. If I had been born in Singapore and had lived here in my formative years, I would have had my own personal memory, filled by sights and sounds and smells, by trauma, trivial incidents and cultural uniqueness. I would have an inner memory from the tales, gossip or irrelevant information my mother or grandmother, father, uncles or passing acquaintances would have told me. Such a well of memory upon which to intuitively draw is a prerequisite for the writer of fiction.

Much later, I realised that this was why I had enjoyed listening to oral history interview tapes at the National Archives. I had been building a memory upon other people’s memories. I had so much preferred the recordings, with their vivid personal recounting, to the reading of memoirs and history books because this oral history was a live and direct personal transmission of memory straight into my own mind.

Appropriating Memories for Myself

These realisations came to me much later. For a while, I stopped writing and had given up all hope that I could produce the book I had originally planned to write. Months went by.

Then, one night, I awoke at 2 am with words crowding my head and a group of characters waiting for me in a place I had not anticipated meeting them – on a trolley bus trapped in that first communist riot of 1927. That incident I had read about in the policeman’s memoir had been tucked away in my subconscious but had now risen to the surface of my mind. I had, in fact, all but forgotten the episode and had not even included it in my original plan for A Different Sky. Yet now, the event was demanding that I make immediate use of it.

In the dead of night, I got up and went to my desk and began at once to write, buoyed by the words in my head that soared ahead of me, picking up with ease the strangest of details. And I knew I had to discard my earlier 200 laboured pages and start again from this new beginning, for now I had found my writer’s voice. Much of what I wrote that night remains in the first chapter of A Different Sky.

It was only when I had completed the task of writing A Different Sky, and the novel published, that I found I was free to unravel the conundrum of its writing and the issue of memory. I realised I had initially started writing before I had fully digested the “memory” I had accumulated so carefully through my research. In order to write fiction, the fabricated historical memory had to be absorbed to such a degree that it could have been my own personal recall. Only then could I unconsciously draw upon it as if it were my own memory in the historical context of A Different Sky.

Like all historical novels, A Different Sky is a re-creation of what might have been. Within this imaginary space, the historical novel often establishes an alternative interpretation of a past that in some instances might have been distorted or even silenced. Between the past being written about and the present in which the writer lives, it is inevitable that history will be rewritten, and this rewriting will, to some extent, reflect the image of the writer.

In spite of such possible variance, making sense of the complexities of the past is one of the prime inspirations and responsibilities of a historical novelist. As a means by which the past can be opened up to the present, the historical novel is uniquely positioned to illuminate and re-examine historical events. The great achievement of successful historical fiction is that it becomes a literary archive from which the reader can retrieve not only lost memories, but also capture new fields of experience, connecting with the past to understand it anew.

|

| In 2014, Dr Meira Chand donated her manuscripts, typescripts and research materials relating to A Different Sky to the National Library, Singapore. The book is available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries (Call nos.: RSING S823 CHA and CHA) as well as for digital loan on NLB OverDrive. It also retails at major bookshops in Singapore. |

Dr Meira Chand’s multicultural heritage is reflected in the nine novels she has published. A Different Sky made it to Oprah Winfrey’s reading list for November 2011, and was long-listed for the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award in 2012. Her latest book, Sacred Waters, was published in 2018. She has a PhD in Creative Writing, and lived in Japan and India before moving to Singapore in 1997.

Dr Meira Chand’s multicultural heritage is reflected in the nine novels she has published. A Different Sky made it to Oprah Winfrey’s reading list for November 2011, and was long-listed for the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award in 2012. Her latest book, Sacred Waters, was published in 2018. She has a PhD in Creative Writing, and lived in Japan and India before moving to Singapore in 1997.

NOTES

-

Clendinnen, I. (2006, September). The history question: Who owns the past? Quarterly Essay, issue 23. (Not available in NLB holdings); Grenville, K. (2006). The secret river. Edinburgh: Canongate. (Call no.: GRE) ↩

-

Dixon, A. (1935). Singapore patrol: The experiences of a detective-officer in Malaya. London: Harrap. (Call no.: RCLOS 915.95 DIX-[RFL]) ↩