The Sticky Problem of Opium Revenue

At one point, half of Singapore’s annual revenue came from taxing opium. Diana S. Kim looks at how the colonial government managed to break its addiction to easy money.

On 16 September 1952, the government in Singapore found itself in a delicate situation over the sum of $55 million. This money was sitting in the Opium Revenue Replacement Reserve Fund, an entity set up in 1925 that contained nearly 30 years’ worth of revenue collected by the British colonial authorities from legal opium sales in Singapore. It seemed reasonable, opined one member of the Legislative Council, Charles Joseph Pemberton Paglar, to spend at least part of the money raised from the drug to help those suffering from its ill effects.1

At the time, opium addiction was a deeply controversial social issue. Only the year before, a new Dangerous Drugs Ordinance had rendered opium consumption in Singapore an offence punishable by imprisonment. Some denounced the government’s punitive turn while others welcomed it as a “corrective” approach as “the prison acts as a hospital and reformatory at the same time and it is better than either alone”.2 But both sides shared similar dismay at the persistence of opium-smoking and its associated problems. At least 2,000 illegal opium saloons were operating in Singapore then and opium-related crime, tuberculosis and suicide rates were high.3

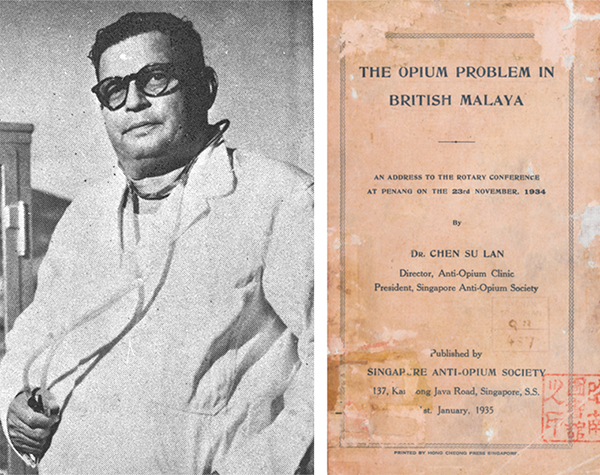

Moreover, the law was being made a mockery of, according to the physician and social reformer Chen Su Lan. Chen, the elected president of the Singapore Anti-opium Society in 1930, worried how “opium addiction, instead of being regarded as an offence was being used as a legitimate excuse for illegal possession of opium”.4 Like Chen, Paglar was a medical doctor and, in his capacity as the Progressive Party’s elected representative for Changi, also a longstanding advocate for better care of the sick and poor.5 He requested that some of the funds be released to treat opium addicts in need.6

The government, however, rejected Paglar’s proposal and informed him that the Opium Revenue Replacement Reserve Fund was “not available for the curative treatment of needy addicts”.7

(Left) Charles Joseph Pemberton Paglar, a medical doctor and member of the Legislative Council. In 1952, he proposed using part of the Opium Revenue Replacement Reserve Fund to help opium addicts. Eric Paglar Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

(Right) Dr Chen Su Lan, as Director of the Anti-Opium Clinic and President of the Singapore Anti-Opium Society, delivered an address on the opium problem in British Malaya at the Rotary Conference held in Penang on 23 November 1934. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession no.: B02890349B).

(Left) Charles Joseph Pemberton Paglar, a medical doctor and member of the Legislative Council. In 1952, he proposed using part of the Opium Revenue Replacement Reserve Fund to help opium addicts. Eric Paglar Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

(Right) Dr Chen Su Lan, as Director of the Anti-Opium Clinic and President of the Singapore Anti-Opium Society, delivered an address on the opium problem in British Malaya at the Rotary Conference held in Penang on 23 November 1934. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Accession no.: B02890349B).

In 1953, the $55 million was transferred to a different account – the vaguely named Special Reserve Fund.8 By the time the British granted Singapore internal self-government in 1959, this fund had been absorbed into the general revenue surplus, without any traceable connections to its opium origins. The disappearance of the huge sum of money marked the quiet end to a radical arrangement that helped justify a deeply controversial aspect of 20th-century British colonial rule in Singapore: fiscal dependency on opium taxes.

Opium and Colonial State Building in Singapore

From the earliest years, the colonial government had levied taxes on opium consumption. At its peak in the 19th century, opium accounted for over 50 percent of the revenue collected in the Straits Settlements (comprising Singapore, Melaka and Penang). Until 1909, Singapore auctioned off rights to private interest groups to operate opium tax farms. Thereafter, the government established a monopoly that collected licence fees directly from state-owned opium retail shops.

During the first half of the 20th century, opium tax revenue was essential to Singapore because it constituted a large proportion of the territory’s finances and there were few viable options to replace it. Opium helped pay for the building and maintenance of public infrastructure like roads, bridges and lighthouses, and financed the upkeep of the harbour and wharves at the heart of Singapore’s economy.9

Metropolitan Britain and other British territories also profited from the opium revenue: in 1914, the Straits Settlements contributed the largest share of military funds to the Imperial Exchequer among the Crown Colonies, more than half of which came from opium revenue.10 In the early 1920s, government opium sales represented 75 percent of the colony’s excise tax and internal revenue, or 55 percent of its total revenue.11

From an administrative perspective, Singapore’s fiscal dependency on opium had long been worrisome, but it was not necessarily an actionable problem. For one, opium was regarded as a predominantly Chinese realm of profit-making that the British authorities tended to avoid interfering with. Since the early 19th century, migrant workers from southern China, many of whom smoked opium, had provided the essential labour for pepper and gambier plantations as well as in tin mines across the Malay Peninsula that sustained the colonial economy. Powerful Chinese entrepreneurs competed to run the Singapore opium tax farm and paid enormous licence fees to monopolise the sale and distribution of opium.

A coloured zincograph print of a poppy flower and seed capsule (Papaver somniferum) by M.A. Burnett, c. 1853. This species of poppy is used to produce opium. Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

A coloured zincograph print of a poppy flower and seed capsule (Papaver somniferum) by M.A. Burnett, c. 1853. This species of poppy is used to produce opium. Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

However, the colonial government did not have a clear idea how these Chinese-run opium tax farms operated financially. As late as 1903, Governor of the Straits Settlements Frank Swettenham admitted to the Colonial Office that “no individual and no Department has made any study of the question and there is no one with experience to whom to appeal for advice on the subject”.12

Among administrators stationed in the Straits Settlements, there was a weak conviction about the necessity of official action addressing the harms and social ills caused by opium. In the heyday of social Darwinism and evolving scientific knowledge about the drug’s addictive properties, Europeans held that the so-called Asiatic races were less injured by opium and used this to justify its commercial sale in Southeast Asia. As a result, the British often discounted social demands in their colonies to ban opium-smoking.

In 1906, despite protests citing the harmful effects of opium to the Chinese community in Singapore, Penang and Kedah, records reveal that local bureaucrats were skeptical such collective action conveyed actual popular anti-opium sentiments. As Charles J. Saunders, the Acting Secretary for Chinese Affairs, explained to the Straits Settlements Opium Commission, “I do not think that either the idea or the movement is indigenous.” More likely, he believed it was due to the loud machinations of “zealous and religious people” such as Protestant missionaries in Singapore and certain members of the Chinese Chamber of Commerce.13

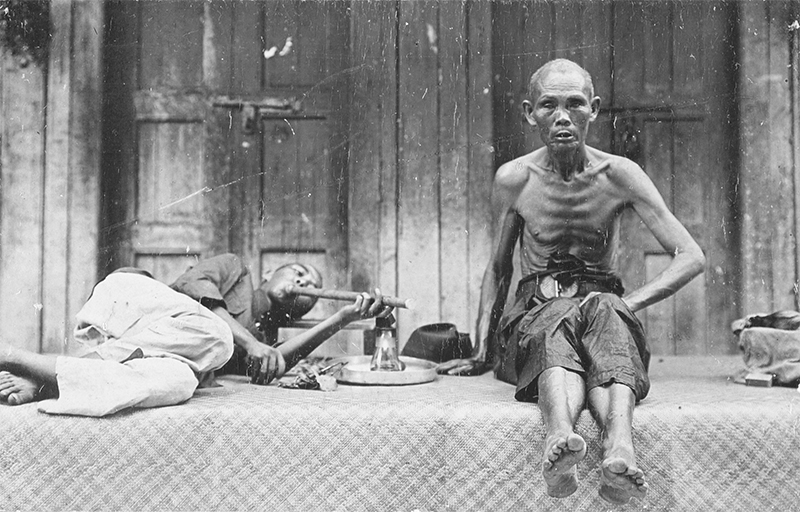

Emaciated Chinese labourers smoking opium, late 19th century–early 20th century. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Emaciated Chinese labourers smoking opium, late 19th century–early 20th century. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Official reluctance to end opium taxation was further linked to the daunting task of finding and replacing such a large source of revenue. The possibility of raising stamp fees and kerosene taxes was considered, or perhaps higher excise taxes on tobacco and alcohol. Instituting estate taxes or a state monopoly over pawnbroking were also examined.14

Chinese-specific taxes were looked at, including a poll tax on migrants from China, taxes on their remittances and savings, as well as an income tax on wealthy Chinese inhabitants who owned property in the Straits Settlements. According to Dr David Galloway, Head of the Singapore Medical Association, taxes targeting the Chinese were justified because declining opium consumption would most likely benefit the health and welfare of the Chinese community.

These possibilities were more easily imagined than done. Any alternative revenue source was too small. “[T]o produce anything like the same revenue [from opium], the poll tax would have to be $10 or $15 per head,” fretted one administrator.15 Chinese-specific taxes were seen as highly discriminatory, as the eminent doctor and prominent community leader Lim Boon Keng pointed out, because if Singapore was able to eradicate opium consumption, it was hardly to the advantage of the Chinese only, but also “to the general advantage of the State”.16 It was also obvious that social backlash would occur. T.S. Baker, the legislative councillor representing the Singapore Chamber of Commerce, pointed out that an income tax that fell disproportionately on the Chinese was a fiscal strategy “fifty if not one hundred years in advance of the times” and would lead to “dishonesty and deception” while driving away “capital business, trade and people”.17

Opium Revenue Reserve Replacement Fund

It was a complex and deep-seated problem of fiscal dependency and decades would pass before a viable solution emerged. The impetus came partly from external pressures. During the interwar period, there were strong international anti-opium feelings, at once drawing upon and reconfiguring the demands of religiously inspired reformers and transnational activists who had long framed the harm caused by opium as serious moral problems and lobbied for the drug’s prohibition.18 The end of World War I had helped consolidate multilateral cooperation among European empires to end opium’s commercial life, not least because ratifying pre-war agreements to restrict the drug was made a condition of the 1919 Versailles peace treaties.19

In this context, the fiscal practice of taxing opium consumption was a potential source of embarrassment that would damage imperial prestige and repute. During a meeting in Geneva in 1924–1925, Britain faced accusations of “being influenced by money considerations in postponing a desirable social reform”.20 Diplomats and politicians in London pressed the colonial authorities in the Straits Settlements to devise an arrangement that would help signal both the Empire’s will and ability to end its reliance on a controversial source of revenue.

Yet, neither the abstract demands of an international community nor the worries of imperial leadership about losing face before other empires provided a practical way to wean Singapore off its opium revenue. This was a deeply entrenched problem of colonial governance that long predated the global rise of anti-opium norms. It would take someone with intimate knowledge of the nitty-gritty workings of Singapore’s opium-entangled fiscal regime, who was creative within the narrow bounds of bureaucratic imagination, and with just enough hubris to take on the enormous task of reinventing the economic foundations of the British colonial state. That man was Arthur Meek Pountney.

“I am extremely fond of figures,” professed the Oxford mathematics graduate who also took great pride in being an expert in matters of opium and Chinese affairs across the Malay Peninsula. In 1908, as Selangor’s Assistant Protector of Chinese, he produced what his colleagues called “the most complete… the most instructive set of tables and notes” on Chinese migrants and opium consumption.21

Throughout his administrative career, Pountney capitalised on his talent for numbers: he moved to Singapore in 1910 to oversee the census, then joined the Treasury Department in 1913 and became Treasurer in 1917 before finally assuming the position of Financial Adviser to the governor. In this capacity, Pountney designed the Opium Revenue Reserve Replacement Fund, calling it “the apotheosis of that part of my career which has been long and intimately connected with the opium question as it affects Malaya”.22

The idea was simple, Pountney explained to the Straits Settlements Legislative Council on 25 August 1925. The colonial government would set aside $30 million – which would come from Singapore’s currency surplus – part of which would be transferred to an investment fund that “after 5 years… give 4 percent interest, an annual income of $1,460,000”.

This was not a huge sum, acknowledged Pountney, as it would amount to less than a quarter of opium revenue accrued to the colonial state’s coffers. Thus, the shrewd bureaucrat planned for the equivalent of 10 percent of the colony’s annual revenue to be transferred into the reserve fund to top it up. According to Pountney: “[A]ssuming that the fund was left absolutely intact, and growing at compound interest, it would amount in 5 years… to a sum which would give an annual income of $2,050,000” and “within a reasonable time… might come to something approximating the revenue from opium”.23

By design, the fund was a long-term arrangement. Indeed, it would be a very long-term income stream, with increasingly larger returns. Poutney estimated that in 10 years, “the income would be $3,100,000; in 15 years $4,360,000; and 20 years $5,900,000”. This administrator’s prosaic calculations contained a remarkably bold vision of British colonial governance and its prospects as a permanent and stabilising force. Pountney announced that he “did not want to leave to posterity an annual bill which it cannot meet without a very great reduction of efficiency or a drastic reduction in the maintenance and upkeep of the systems and institutions of Government”.24

Observers remarked that the Opium Revenue Reserve Replacement Fund was a “financial innovation of a startling nature for which, as far as we know, no precedent exists”.25 Some lauded the fund as anchored in considerations of both honour and prudence. Legislative Council member E.S. Hoses admired how the fund provided “tangible proof to all the world” that despite the dependence on opium revenue, it did not “interfere with a honest and sustained endeavor to overcome the evil of [opium] consumption within our borders”.26

Others worried that “the existence of so large a fund… will tend towards profligate expenditure on the part of the Government spending departments” and the surplus would be “liable to be diverted to other uses”.27 The Singapore Chamber of Commerce sharply criticised Pountney’s “indulgence of posterity” at the expense of the welfare and needs of people in the present. Within the Colonial Office in London, suspicions were also voiced about the possibly impure intentions of administrators in Singapore to “build up a fund so large, that the interest upon them would equal the opium revenue which is to be lost and the Governments would then live like rentiers upon their savings”.28

Each perspective contained elements of potential truth. There was a clear instrumental value to the mere existence of this arrangement as it enabled the British to claim on the international stage that they were making a genuine effort to curb opium consumption in their colonies and asserting the moral authority of imperial rule. However, there was also a blatant lack of transparency as to how the colonial government would use what quickly became a very large pot of money. By the end of its first year of operations, the fund had increased by $4 million to $34 million, a sum that far exceeded Pountney’s original projections. Yet both perspectives missed a deeper story about the transformation of the colonial state and how a bureaucratic solution was emerging to address Singapore’s long-standing problem of fiscal dependency on opium sales under British rule.

Managing the Fund

The bureaucratic solution to a century-old problem of fiscal dependency would soon morph into an abstract form of investment wealth that helped sustain the Empire and finance myriad projects for colonial development. The fund’s management was entrusted to the Crown Agents, a quasi-governmental office of the Treasury in London, and invested across the world. In 1926, the $34 million generated another $4 million in net value through purchasing colonial stocks in Nigeria, Jamaica, Sierra Leone, the Union of South Africa, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), Hong Kong and Canada. Within 10 years, vestiges of the fund could be found in nearly all territories under British rule, with a total net value of $62 million.29

Closer to home, the fund helped support the Perak Electric Power Company, which had long supplied electricity to the Kinta Valley, one of the main tin mining areas of the Malay Peninsula. The British feared the company would default on a loan and used the opium funds to transform the loan into an investment to avoid losses from the company’s possible liquidation or restructuring.30

The fund took on a longevity that extended far beyond what had been an imaginable future in interwar Singapore. Even the Japanese invasion in 1942, which replaced the Union Jack with the Rising Sun, and subsequent Occupation (1942–45), did not fundamentally weaken the fund.

During the Occupation years, the Japanese Military Administration and local community leaders in Singapore both disavowed and also benefitted from the revenue generated from opium’s commercial sale.31 And while the British no longer ruled Singapore, they still gained because the Opium Revenue Replacement Reserve Fund was held in sterling securities in London and continued to collect compound interest.

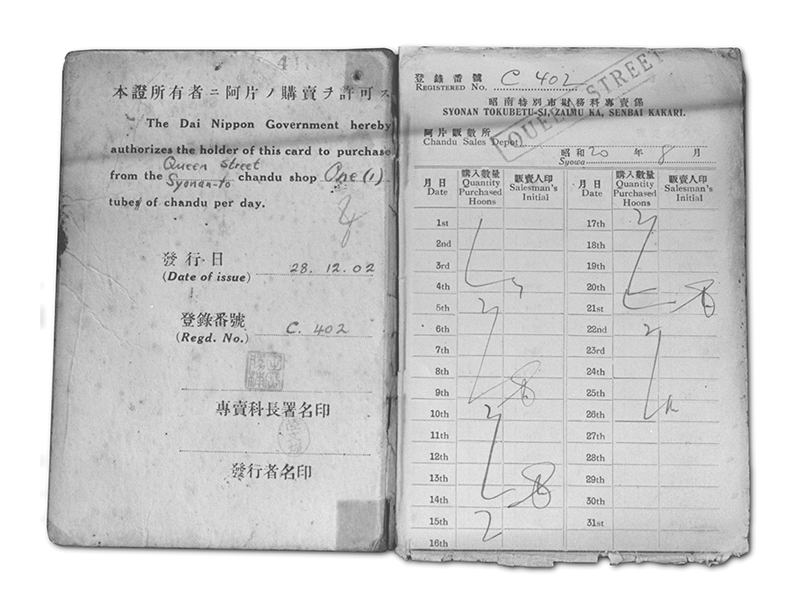

An authorisation card to purchase chandu (opium) from Queen Street in 1942, during the Japanese Occupation. Chew Chang Lang Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

An authorisation card to purchase chandu (opium) from Queen Street in 1942, during the Japanese Occupation. Chew Chang Lang Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

It is still not completely clear what exactly happened to the fund following the end of World War II, after Japan’s defeat and the return of the British to Singapore. Hopefully, this will be a topic for future research. What is evident in currently available and declassified archival records is that the fund carried over to postwar Singapore and became a controversial topic of much public debate. In June 1946, the prominent lawyer Roland Braddell argued that the opium funds belonged to the public, but had never been subject to proper accounting. “We do not know at what figure they stand today,” he noted.32 The following year, a committee report of the Singapore Association estimated that approximately $9 million was missing from the fund because the British had utilised all of the interest that had accrued during the war, instead of reinvesting the money in securities in London.33

Such concerns about the fund’s murkiness were tied to larger questions about Singapore’s future – if and how the legacies of colonial opium revenue might help finance its postwar recovery, where opium entangled funds might fit into Singapore’s assets and liabilities, and what vision of posterity should guide a government in the protracted process of decolonisation.

Any solution to this problem – so deeply entwined with the foundations of British colonial rule in Singapore and accumulated for over a century – would necessarily be imperfect and partial. By 1952, when Charles Paglar’s request to use the Opium Revenue Replacement Reserve Fund for addict treatment was denied, it had assumed a strange ambiguity, its only clarity being that the fund not be used for the people from whom it had been collected, i.e. opium smokers in Singapore. Questions regarding its actual purpose and legitimate use were sidestepped as the fund was effectively renamed in 1953 and absorbed into a Special Reserve Fund to assist the government’s commitments to development and public infrastructure improvement.34

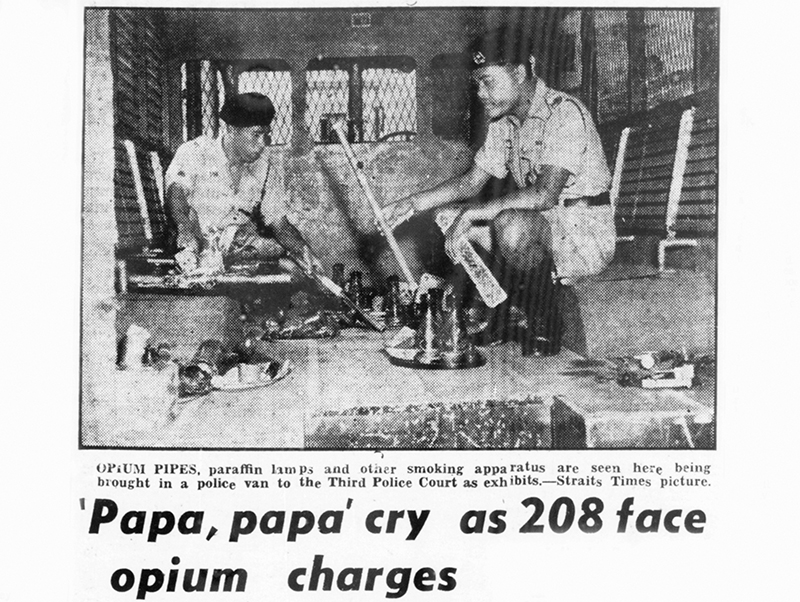

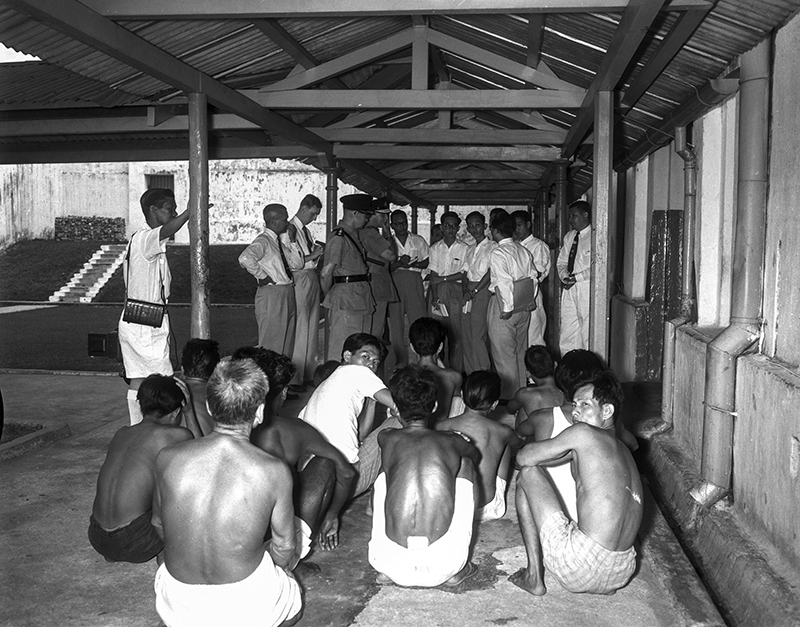

In July 1952, police raids in Singapore resulted in the arrest of more than 200 opium addicts and opium den operators. The Straits Times, 8 July 1952, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

In July 1952, police raids in Singapore resulted in the arrest of more than 200 opium addicts and opium den operators. The Straits Times, 8 July 1952, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

The same year that the fund was renamed, a solution for addressing the problem of Singapore’s opium addicts arose for discussion. Official plans for establishing a rehabilitation facility on St John’s Island were put forward, garnering much public support. “St John’s is ideal,” said physician and social reformer Chen Su Lan, calling it a “quiet, restful spot ‘away from it all’ with plenty of fresh air, sunshine, and the sea” that would help opium addicts “forget their habit”.35 Paglar concurred, calling it a “wonderful gesture” by the government.36 Two years later, the St John’s Opium Treatment Centre opened its doors with much fanfare, commanding the attention of the international community and medical experts as “the first in the world established solely to fight opium addiction”.37

Visitors to the Opium Treatment Centre on St John’s Island, 1957. The facility opened in 1955 to treat and rehabilitate opium addicts. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Visitors to the Opium Treatment Centre on St John’s Island, 1957. The facility opened in 1955 to treat and rehabilitate opium addicts. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

|

| This essay is based on research that led to Diana S. Kim’s Empires of Vice: The Rise of Opium Prohibition Across Southeast Asia (2020). The book is available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries (Call nos.: RSING 364.1770959 KIM and SING 364.1770959 KIM). It also retails at major bookshops in Singapore. |

Dr Diana S. Kim is an Assistant Professor at Georgetown University in the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service. She is the author of Empires of Vice, a comparative study of the rise of opium prohibition in British Burma, Malaya and French Indochina.

Dr Diana S. Kim is an Assistant Professor at Georgetown University in the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service. She is the author of Empires of Vice, a comparative study of the rise of opium prohibition in British Burma, Malaya and French Indochina.

NOTES

-

No fund money to cure opium addicts. (1952, September 17). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Truth about opium. (1952, July 4). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

2,000 opium saloons. (1952, July 5). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 4 Jul 1952, p. 6. ↩

-

Blackburn, K. (2017). Education, industrialization and the end of empire in Singapore (p. 71). New York: Routledge. (Call no.: RSING 370.95957 BLA) ↩

-

Blythe explains opium fund. (1952, September 17). Singapore Standard, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 17 Sep 1952, p. 4. ↩

-

Singapore. Parliament. (1956, November 20). Liquidation of special reserve fund (col. 815). Retrieved from Singapore Parliament website. ↩

-

Kim, D.S. (2020). Empires of vice: The rise of opium prohibition across Southeast Asia (p. 35). Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. (Call no.: RSING 364.1770959 KIM), citing Report from the Colonial Military Contributions Committee, Hong Kong Opium Revenue, 9 April 1914, National Archives of the United Kingdom, Kew (TNA)/T1/11642/11908. Also see Kim, 2020, p. 128, citing House of Lords, 24 July 1891, vol. 356, cc. 214-234. Retrieved from UK Parliament website. Also see The coalition stations of the world. The Coal Trade Journal, 1896, vol. 28, p. 207. Retrieved from HathiTrust website. ↩

-

Kim, 2020, p. 35, citing Report from the Colonial Military Contributions Committee, Hong Kong Opium Revenue, 9 April 1914, National Archives of the United Kingdom, Kew (TNA)/T1/11642/11908. ↩

-

Kim, 2020, p. 125, citing Straits Settlements. (1921). Blue book for the year…. Singapore: Government of the Colony of Singapore. (Microfilm nos.: NL1153; 1155); The Council. (1925, October 6). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Kim, 2020, p. 131, citing Swettenham to Secretary of State for the Colonies, 9 October 1904, TNA/CO 271/292. ↩

-

Kim, 2020, p. 136, citing C. J. Saunders, 8 September 1907, Straits Settlements Opium Commission (SSOC) 1908, vol. 2, p. 100. ↩

-

Kim, 2020, p. 137, referring to SSOC 1908, 3 January 1908; 12 October 1907; 8 September 1907. ↩

-

Kim, 2020, p. 139, citing C. J. Saunders, 8 September 1907, Straits Settlements Opium Commission (SSOC) 1908, vol. 2, p. 100. ↩

-

Kim, 2020, p. 139, citing National Library Board. (2015, December 31). Lim Boon Keng written by Ang Seow Leng & Fiona Lim. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website; 17 August 1907, SSOC 1908, vol. 2, p. 51. ↩

-

Kim, 2020, p. 139, citing Income tax protest. (1911, January 28). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Rimner S. (2018). Opium’s long shadow: From Asian revolt to global drug control. Harvard University Press. (Not available in NLB’s holdings) ↩

-

Kim, 2020, p. 125. On the Geneva Opium Conferences, see Goto-Shibata, H. (2002, October). The International Opium Conference of 1924–25 and Japan. Modern Asian Studies, 36 (4), 969–991. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

Kim, 2020, p. 264, citing The Council. (1925, August 24). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Kim, 2020, pp. 145–146, citing The Straits Times, 6 Oct 1925, p. 9. Pountney designed a separate Opium Revenue Reserve Replacement Fund for the Federated Malay States (FMS), which began with $10 million and added yearly contributions of 15 percent of collected opium revenue. In this essay, I focus on the Straits Settlements fund. On its complex relationship with, and differences from, the FMS opium fund, see Kim, 2020, pp. 121, 143–151 and Cooray, F. (1947, July 15). Chandu shops follow gambling farms. The Malaya Tribune, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Kim, 2020, pp. 145–146, citing The Straits Times, 6 Oct 1925, p. 9. ↩

-

Kim, 2020, p. 121, citing Report of Opium Revenue Replacement and Taxation Committee, 1928. ↩

-

Kim, 2020, p. 146, citing Straits Settlements Legislative Council Proceedings, 1925. ↩

-

Kim, 2020, 147, citing Report of the Subcommittee appointed by the Straits Settlements Association, 6 April 1926, TNA/CO 273/534/9. ↩

-

Kim, 2020, p. 151, citing Straits Settlements Blue Book, 1934. ↩

-

Kim, 2020, p. 151, citing from Clementi to Passfield, 11 September 1930, TNA CO 717/66. ↩

-

Community leaders praise authorities’ opium policy to be stamped out by gradual curing of addicts. (1942, September 27). Syonan Shimbun, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Living on our savings? (1947, June 17). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Kim, 2020, p. 197, citing Sabaratnam, S. (1948, October 13). S’pore’s $15 million opium racket. The Malaya Tribune, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Govt. to put by boom surplus. (1953, October 20). The Singapore Free Press, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG ↩

-

St. John’s is ideal, says Dr. Chen. (1953, September 13). The Straits Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Island camp to cure opium addicts. (1954, May 25). The Singapore Free Press, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Morgan, P. (1955, February 5). Whole world watches this S’pore experiment. The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩