Love Is a Many-Layered Thing

What lies in this vale of tiers? Christopher Tan delves into lapis legit, the cake as famous for its exacting recipe as for the unparalleled flavour of its buttery layers.

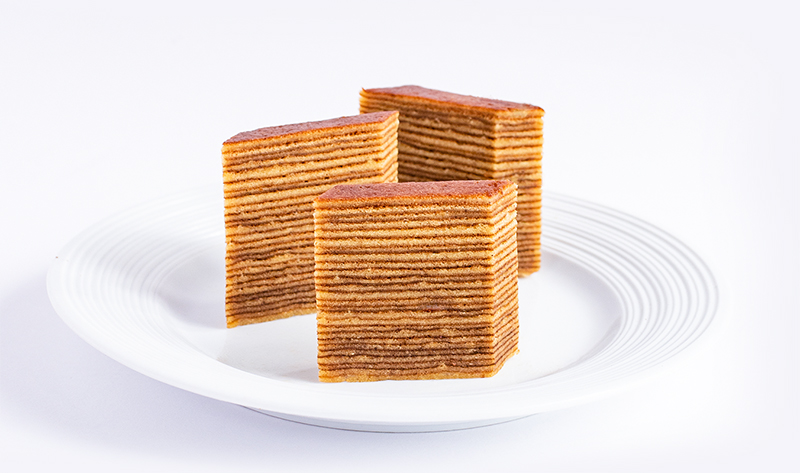

The author’s home-made kueh lapis legit. This is an iconic cake for Indonesians, Malays and the Peranakan Chinese. Courtesy of Christopher Tan.

The author’s home-made kueh lapis legit. This is an iconic cake for Indonesians, Malays and the Peranakan Chinese. Courtesy of Christopher Tan.

When I was young, kueh lapis legit1 would announce its presence in my family kitchen long before anyone got to taste it. The first portent was the careful shepherding of precious bottles of spice powders and brandy. The next sign was the buying of many eggs and much butter. On baking day, the kitchen thrummed with signals: the loud rhythm of batter vigorously beaten; the steady cadence of spread batter thinly, grill it until brown, press out bubbles, brush with butter, then repeat; and the rippling scent-waves of sizzling butter and caramelising crust. Anticipation ran at a fever pitch, or perhaps that was just the heat nimbus of our Baby Belling oven.

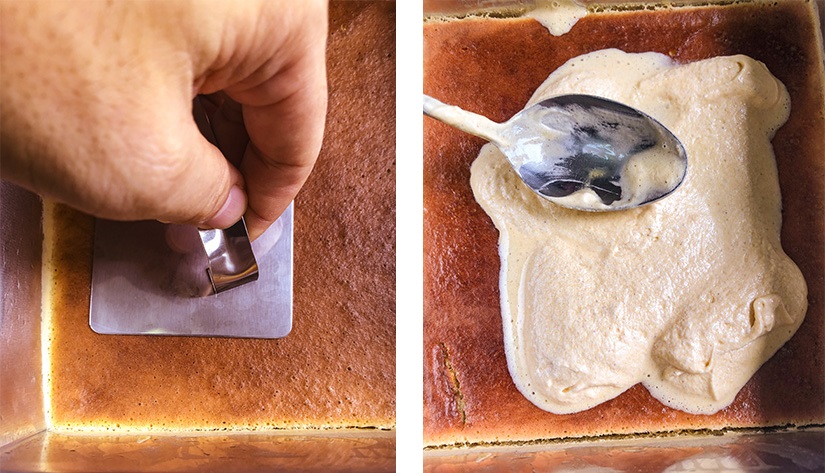

Pressing a freshly baked lapis legit layer to flatten and smoothen it, and spreading batter for the next layer. Courtesy of Christopher Tan.

Pressing a freshly baked lapis legit layer to flatten and smoothen it, and spreading batter for the next layer. Courtesy of Christopher Tan.

Kue lapis legit and its sister confection spekkoek (more of that sisterhood later) are iconic cakes for Indonesians, Malays – especially those with some Javanese heritage – and Peranakan Chinese. Major festivals such as Hari Raya and the Lunar New Year would not be complete without tables graced by these tiered touchstones. These communities have roots and branches in the milieus of maritime Southeast Asia’s Dutch colonial era, which saw the flowering of many hybrid foodways. “Most of us who live in cities known for rich colonial history, like Jakarta, Palembang, Bangka, Semarang, Surabaya and Bandung, are familiar with lapis legit and spekkoek as [legacies of] Dutch influence,” says Indonesian food writer, author and restaurant pundit Kevindra Soemantri.2

Modern makeovers have spawned a multiplicity of lapis varieties – patterned in bright colours; flavoured with fresh or dried fruit, cheese or coffee or chocolate; rolled up into logs; or carved and rearranged like intricate marquetry. A comprehensive 1986 Indonesian recipe book, Hidangan Ringan: Party Snacks, includes 11 different variations on the theme, to the tune of cempedak, durian, mocha and more.3 However, the classic version remains the most revered incarnation: a soft, rich European-style butter cake infused with spices native to the Indonesian Archipelago, cooked one layer at a time under a hot grill.

A modern rolled variation of kue lapis legit with a flower-shaped cross-section. Courtesy of Christopher Tan.

A modern rolled variation of kue lapis legit with a flower-shaped cross-section. Courtesy of Christopher Tan.

Peeling Back the Years

Trawling through vintage recipes, I found that this basic template has persisted with little alteration for well over a century. The only major differences between old and modern recipes are the heat source – formerly charcoal, these days usually an electric oven element – and the now-frequent addition of condensed milk and/or milk powder to the batter, perhaps to mimic the stronger flavours and higher protein content of yesteryear’s imported butter.

The Spekkoek (Kwee Lapies) recipe in the 1895 book, Recepten Van De Haagsche Kookschool (Recipes from The Hague Cooking School), is fully consonant with modern recipes, albeit its “65 cloves” might be a bit much for most of us today. It directs the cook to cream butter, sugar, eggs and flour into a batter “in the usual way”, flavour it with very finely ground spices, bake it in layers, smearing butter over each layer when it is done, and finally to store the cake in a tightly sealed tin, where it will keep for “a long time”.4

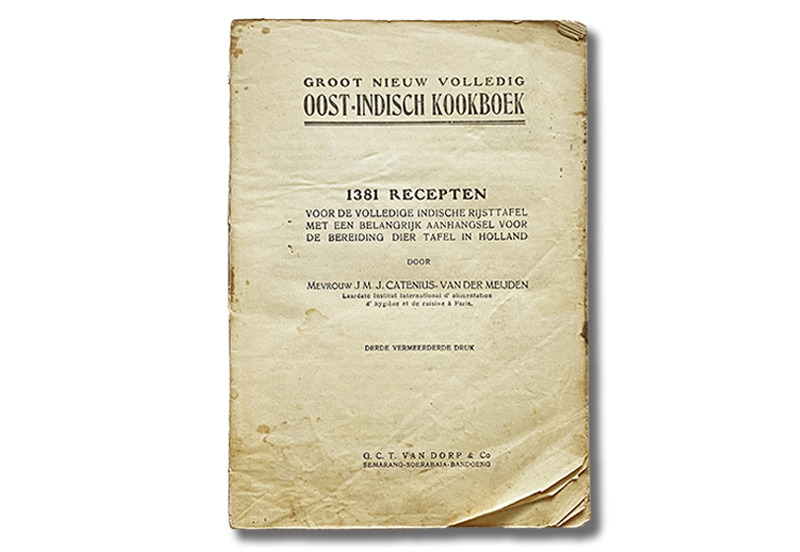

The 1925 Groot Nieuwe Volledig Oost-Indisch Kookboek (Great New Complete East Indies Cookbook)5 collates three spekkoek recipes in its inlandsche bakken (native baking) chapter. One of them has only three thick sponge cake layers, baked individually and then sandwiched with “some sort of jelly” – we know this style today as kue lapis surabaya, koningskroon (“king’s crown cake” in Dutch) or bahulu lapis.

Title page of Groot Nieuwe Volledig Oost-Indische Kookboek, published in 1925. It contains nearly 1,400 recipes, including three spekkoek recipes in its inlandsche bakken (native baking) chapter. Image reproduced from van der Meijden, J.M.J.C. (1925). Groot nieuw volledig Oost-Indisch kookboek [Great New Complete East Indies Cookbook]. Malang: G.C.T. Van Dorp & Co. (Not available in NLB holdings).

Title page of Groot Nieuwe Volledig Oost-Indische Kookboek, published in 1925. It contains nearly 1,400 recipes, including three spekkoek recipes in its inlandsche bakken (native baking) chapter. Image reproduced from van der Meijden, J.M.J.C. (1925). Groot nieuw volledig Oost-Indisch kookboek [Great New Complete East Indies Cookbook]. Malang: G.C.T. Van Dorp & Co. (Not available in NLB holdings).

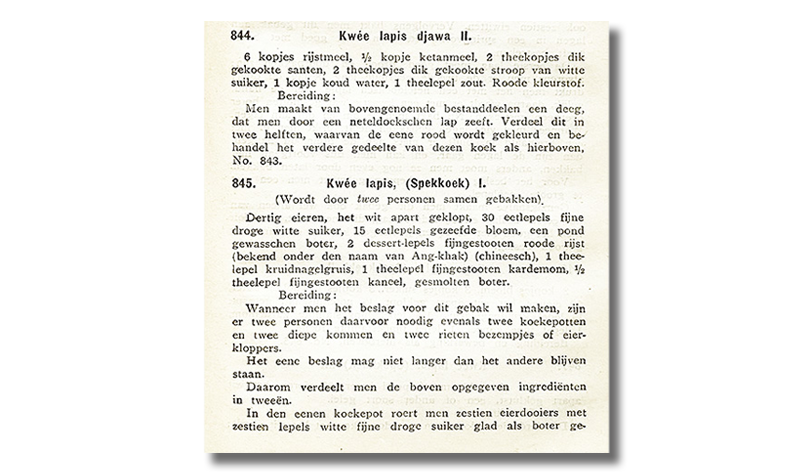

The other two inlandsche recipes are classic spekkoek, and both require “two persons… two skillets… two deep bowls… two wicker brooms or egg beaters” (see text box below) to wrangle one plain white batter and one spiced brown batter, baked in alternating layers. Their formulas otherwise differ: one rests on copious butter and flour, plus cloves, cardamom, cinnamon, nutmeg and mace; the other is more egg-rich, and omits nutmeg and mace but includes crushed ang-khak,6 or Chinese red yeast rice. This last item is especially intriguing given Soemantri’s observation that lapis legit spice blends are “similar to Chinese five-spice… there is a lapis legit recipe that uses fennel also”.7

| BEAT 16 EGG YOLKS… FOR ONE HOUR |

| The following is a 1925 recipe for spekkoek from Groot nieuw volledig Oost-Indisch kookboek (Great New Complete East Indies Cookbook), translated from the original Dutch by Christopher Tan.8 The cake, in its springform pan, may have been baked within a metal vessel with hot coals underneath and/or on top of its lid. Dutch technical prowess at casting such pots led to such vessels being dubbed “Dutch ovens” by other nations in the 18th century. |

| Kwée lapis (Spekkoek) |

| Thirty eggs, the whites beaten separately, 30 tablespoons fine dry white sugar, 15 tablespoons sifted flour, one pound washed butter,9 two dessertspoons finely pounded Chinese red rice or red yeast rice (ang-khak10), one teaspoon clove powder, one teaspoon finely pounded cardamom, two teaspoons finely pounded cinnamon, melted butter. |

| Preparation: |

| To make the batters for this cake, two persons are needed, as well as two pots, two deep bowls11 and two wicker brooms12 or egg beaters. |

| One batter may not stand longer than the other: this is why the above-mentioned ingredients are divided into two lots. |

| In one of the pots, beat 16 egg yolks with 16 tablespoons of fine dry white sugar for one hour,13 until the mixture is as smooth as butter.14 Then add eight tablespoons of flour one by one, then add half a pound of washed butter in small increments while beating constantly. |

| In the second pot, beat the remaining 14 egg yolks with seven tablespoons of the white sugar and seven tablespoons of flour, along with the spices mentioned above, and half a pound of butter. |

| When the batters in the two pots have been well mixed, add the whipped egg whites a spoonful at a time, 16 egg whites for the 16-yolk batter lot.15 |

| The cake is baked in layers in a springform pan,16 which must first be brushed well with butter. |

| The first layer must be thoroughly dry and well cooked: before you add a second layer of the spiced batter, press it down with a muslin-wrapped hand,17 then brush some melted butter over it.18 Then continue to bake the batters alternately in layers. |

| When you have baked four layers, prick the cake with a knitting needle: if nothing adheres to the needle then the layers are done, and you can continue layering; otherwise let them bake for a while longer.19 |

| Use a soup ladle that is not too large to scoop the batter. |

| For convenience’s sake, you can also make this cake using only the first batter, and after every layer is baked, sprinkle it well with the mixed spices, and then top with the batter again. |

Javanese kue lapis and spekkoek recipes in the Groot Nieuwe Volledig Oost-Indische Kookboek, published in 1925. Reproduced from van der Meijden, J.M.J.C. (1925). Groot nieuw volledig Oost-Indisch kookboek [Great New Complete East Indies Cookbook] (p. 305). Malang: G.C.T. Van Dorp & Co. (Not available in NLB holdings). Javanese kue lapis and spekkoek recipes in the Groot Nieuwe Volledig Oost-Indische Kookboek, published in 1925. Reproduced from van der Meijden, J.M.J.C. (1925). Groot nieuw volledig Oost-Indisch kookboek [Great New Complete East Indies Cookbook] (p. 305). Malang: G.C.T. Van Dorp & Co. (Not available in NLB holdings). |

Vintage recipes using a single spiced batter are also common. Besides the Haagsche Kookschool book, Kokki Bitja (Beloved Cook; 1859),20 Oost-Indisch Kookboek (East Indies Cookbook; 1870)21 and Het Nieuwe Kookboek (The New Cookbook; 1925)22 all take this tack for their spekkoek. The Groot Nieuw Volledig Oost-Indische Kookboek also lists a single plain-batter variation, “for convenience”, with the spices merely sprinkled over each layer after the cake is baked. In a Straits Times interview in 1983, famed Kampong Glam culinarian Hajjah Asfiah binte Haji Abdullah called this version kueh baulu lapis, which she would make to sell at her Ramadan bazaar stall near Bussorah Street.23

Dutch-Indonesian chef Jeff Keasberry identifies the two-batter cake with fewer total layers as Indo-Dutch spekkoek that originates from the Dutch East Indies era, a species older than and distinct from what he calls Indonesian kue lapis legit, which uses a single batter and has thinner and more layers – at least 18, according to him.24 Indonesian culinary teacher and author Sitti Nur Zainuddin-Moro also makes the same distinction in her influential cookbook Kue-Kue Manasuka (Kue You Will Like; 1980), naming the two-batter version Sepekuk Biasa (ordinary spekkoek), and the other lapis legit.25

Dutch-Indonesian chef Jeff Keasberry identifies the two-batter cake with fewer total layers as Indo-Dutch spekkoek (right) originating from the Dutch East Indies era, a species older than and distinct from what he calls Indonesian kue lapis legit (left), which uses a single batter and has more and thinner layers. Courtesy of Jeff Keasberry.

Dutch-Indonesian chef Jeff Keasberry identifies the two-batter cake with fewer total layers as Indo-Dutch spekkoek (right) originating from the Dutch East Indies era, a species older than and distinct from what he calls Indonesian kue lapis legit (left), which uses a single batter and has more and thinner layers. Courtesy of Jeff Keasberry.

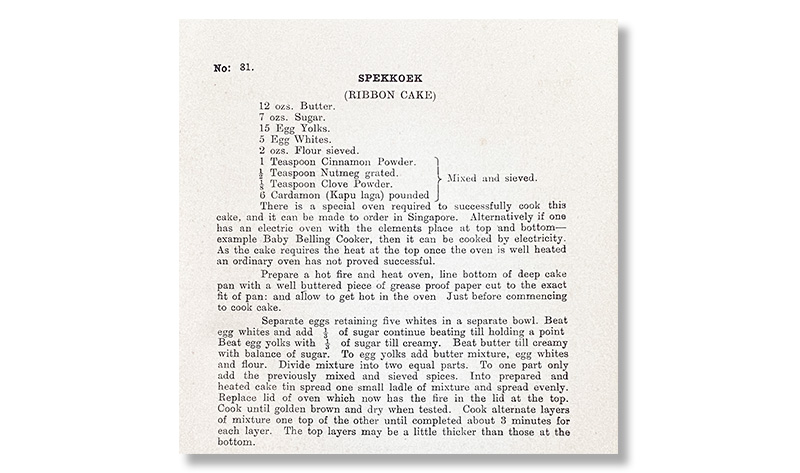

Many examples of both variants have appeared in Singaporean recipe books over the years, although their names are sometimes conflated. Mrs Susie Hing’s landmark 1956 cookbook, In A Malayan Kitchen, includes a spekkoek recipe (and a koningskroon recipe) that Dutch readers from earlier generations would have recognised straightaway.26

A 1957 Straits Times article records a spekkoek recipe by a Mrs Rosaleen Yang, who baked alternating plain and cocoa-spiked batters in “a copper or brass pan”.27 A similar recipe for Lapis Betawi (Batavia, as Jakarta was called under the Dutch) appeared in Berita Harian in 1968, which called for a generous amount of spice to augment the cocoa.28

A vintage brass pan of the type used for baking kueh lapis legit. Note the “scars” on the lid left by hot coals. Courtesy of Christopher Tan.

A vintage brass pan of the type used for baking kueh lapis legit. Note the “scars” on the lid left by hot coals. Courtesy of Christopher Tan.

In 1981, the New Nation published Nonya doyenne and cookbook author Mrs Leong Yee Soo’s single-batter Speckok Kueh Lapis Batavia recipe, which details the importance of pricking each cooked layer with a skewer to deflate bubbles and create microscopic holes for the next layer’s batter to flow in, for better adhesion.29 In 1977, the Straits Times featured a recipe by one Cik Khatijah Ashiblie for Lapis Mascovrish, whose vanilla batter was layered with almonds and raisins.30

Outside of home kitchens, only a few stores in Singapore made or imported spekkoek and kue lapis in the early 20th century. One such establishment was the Java Restaurant (originally Mooi Thien Restaurant) on North Bridge Road – described in a 1950 Straits Times article as being “not unlike a Paris bistro”31 – where founder Lim Djin Hai and his family served both Javanese and European food in the late 1940s. Prior to emigrating to Singapore in 1946, Lim was a caterer in his hometown of Bencoolen (now Bengkulu), where one of his clients was the then Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies. (Java Restaurant later moved to Killiney Road, morphing into the Java Provision Store, where for over 25 years it purveyed home-baked and imported Indo-Dutch goods.)

Building a Mystery

The early origin stories of spekkoek and lapis legit remain largely unknown, despite their widespread popularity. Spekkoek derives from the Dutch words spek koek, meaning “bacon cake”, no doubt an allusion to the cake’s pale and red-brown stripes. However, there seem to be no records in the Netherlands of any layered cake by that name which pre-dates lapis legit, and neither is there such an extant cake there.

The Spekkoek recipe from In a Malayan Kitchen. Spek koek means “bacon cake” in Dutch. Both bacon and cake bear stripes – as can ribbons, as this recipe’s subtitle references. Reproduced from Hing, S. (1956). In a Malayan Kitchen (p. 65). Singapore: Mun Seong Press. (Call no.: RCLOS 641.59595 HIN).

The Spekkoek recipe from In a Malayan Kitchen. Spek koek means “bacon cake” in Dutch. Both bacon and cake bear stripes – as can ribbons, as this recipe’s subtitle references. Reproduced from Hing, S. (1956). In a Malayan Kitchen (p. 65). Singapore: Mun Seong Press. (Call no.: RCLOS 641.59595 HIN).

Some have suggested spekkoek has its origins in the German baumkuchen, the “tree-ring” cake considered the ultimate test and accomplishment of a konditormeister (master pastry chef). However, baumkuchen has a drier texture than spekkoek and is made using a different method: its cylindrical layers are built up around a rotating spit. Also, German records clearly trace its evolution from a dough-based cake in the 1500s into the batter-based form known from the 1700s until today.32 “There is no significant record of Prussian people in Indonesia,” says Soemantri, but “perhaps baumkuchen influenced the original Dutch spekkoek”.33

Here is a curious similarity though: baumkuchen is traditionally flavoured with spices (cinnamon, cardamom, nutmeg, ginger or vanilla), citrus, nuts (most often almonds) and liquor. The oldest spekkoek recipe I have come across, from Kokki Bitja, calls for clove, cardamom, white pepper, jeruk cina (mandarin orange) zest, kenari nuts and brandy. Mere coincidence or distant cousinhood?

A more plausible progenitor for kue lapis legit may be the layer cakes traditionally made in southern China to celebrate the annual Double Ninth festival – recipes which travelled to maritime Southeast Asia with the Chinese diaspora. Chiefly rice-based, these cakes are steamed layer by layer, frequently with alternating batters of different colours, often tinted with – yes – red yeast rice. Chinese communities in Southeast Asia still make these today; in Indonesia they are simply called kue lapis, but old Dutch and Indonesian cookbooks identify them as kue lapis cina34 or kue lapis jawa. In Kue-Kue Manasuka, Sitti Nur Zainuddin-Moro records a Batavian recipe for a red and white version called “Lapis Merah Putih (Betawi)”.35

The auspicious Chinese saying and wish for success 歩歩高升 (bu bu gao sheng, which means “rising step by step”) is embodied by both steamed and baked lapis. For the Indonesian Chinese, lapis legit “is always related to celebration, and for them, its many layers equal prosperity,” says Soemantri.36

A Nonlinear Lineage

Indeed, kueh lapis legit is nothing if not rich. In my family, we let it sit untouched for at least a couple of days post-baking, so that all the butter and spice can fully permeate its crumb. When at last it falls under the knife, the sight of even, lovely lamina evokes great relief in the baker, who discovers only at this moment if the deck was stacked for success.

So what might have bridged the gap between steamed rice-flour layers and baked wheat-flour layers, and how? Permit me to suggest a trip to Palembang. Now South Sumatra’s capital, Palembang was formerly the capital of the Srivijayan empire, a Buddhist kingdom which endured from around the 7th century to the 13th century. Its trade links with China, South Asia and the Middle East ensured a constant flow of goods, pilgrims, cultures and languages between those regions and the Malay Archipelago. This made Palembang a fertile place for culinary ferment.

The city lays claim to several lapis varieties. Some are modern glosses on the form – made with pineapple jam between strata (lapis nenas), a multi-layered version of the regional pandan-scented specialty bolu kojo (lapis kojo), and so on.37 Two older signature Palembang lapis types are much closer in spirit to spekkoek, baked the same way but with fewer, slightly thicker layers.

One of them, kue maksuba, is made using chicken and/or duck eggs, butter or margarine, sugar, condensed milk and vanilla, with flour in miniscule quantity or, most often, entirely absent. Essentially a hyper-rich custard, kue maksuba has a smooth solidity not unlike the Malay kuih bakar, with less of a cake-like vibe than orthodox spekkoek.

Steamed rice-based kue lapis for sale at a kue pasar (market) in Jakarta. Courtesy of Christopher Tan.

Steamed rice-based kue lapis for sale at a kue pasar (market) in Jakarta. Courtesy of Christopher Tan.

The other lapis variety, kue engkak ketan, has the same ingredients as kue maksuba, plus two key elements: glutinous rice flour, and blondo or glondo – thick coconut milk which has been boiled until some of its oil has separated out. The oily sheen from the blondo and a faint springiness from the glutinous rice flour strongly recall steamed kue lapis cina, while the heavy doses of butter and condensed milk bestow a European richness. However, the airlessly dense wheat-free crumb and the lack of spice means the resemblance to spekkoek is only partial.

Home-made kue engkak ketan, composed of glutinous rice flour, eggs, butter, sugar, condensed milk, and blondo – boiled, oily coconut milk. Courtesy of Christopher Tan.

Home-made kue engkak ketan, composed of glutinous rice flour, eggs, butter, sugar, condensed milk, and blondo – boiled, oily coconut milk. Courtesy of Christopher Tan.

Kue engkak ketan reminds me strongly of another sweet, one from Goa, India. Bebinca, also called bibinca or bibik, is a colonial legacy said to be a Portuguese recipe but tweaked with local ingredients. It has many spekkoek-like traits, first and foremost a very rich batter made of egg yolk and coconut milk, with comparatively little wheat flour, and spiced with cardamom and nutmeg. Bebinca is traditionally “baked” layer by layer – some recipes specify seven layers, others multiples of seven – under a pot lid holding burning wood or coconut husks, with clarified butter brushed over each layer. It must rest for several hours before being sliced. In terms of flavour and texture, bebinca sits squarely between spekkoek and kue engkak ketan.

Bebinca’s creation is often attributed to a (possibly apocryphal) nun named Bibiana or Bebiana at the Convent of Santa Monica in Goa, whose devout sisters were famed for their culinary skills and repertoire of festive sweetmeats.38 Alternative origin stories suggest links with other similarly named Asian baked goods such as the Filipino bibingka and the Macanese bebinca; however, these purported family resemblances are scattered and hard to qualify. For instance, in Macau, bebinca de leite is a baked milk custard and bebinca de inhame is yam cake (wu tau koh in Cantonese), and neither is layered.

That said, there is a Goan bebinca variation made with mashed potatoes and baked in a single layer, which is all but identical to Malay kuih bingka kentang. In fact, many Goan sweetmeats appear to be cognates of Southeast Asian ones. These include kulkuls (crisp shell-shaped pastries), cousins of kuih siput; alle belle (crepes rolled around grated coconut cooked with palm sugar), which are much like kuih dadar; pinaca (roasted rice and coconut pounded with palm sugar and warm spices), the twin of Peranakan kueh dadu; and Goan dodol (rice, palm sugar and coconut milk toffee), which differs from Indonesian dodol only in that Goan cooks use regular rice instead of glutinous rice.

Food historian Janet Boileau quotes Macanese-culture expert Rui Rocha in speculating that Southeast Asian desserts likely travelled westward to Goa, perhaps via Melaka, and were assimilated into local and Catholic culinary and confectionery traditions there.39

Bebinca is also traditional to East Timor, a Portuguese colony up until the 1970s. Though they seem similar, it is unclear whether Timorese bebinca prefigured or instead descended from the Goan version. Such intricately connected and mingled gastronomy is the legacy of centuries of Dutch and Portuguese colonisers contending over the same turf in Asia and around the world. While not as emblematic to Singapore’s Eurasians as sugee cake, spekkoek is also made by that community, whose origins, history and traditions incorporate both Portuguese and Dutch heritage.40

Much More Than Its Seams

Perhaps this is how the story could have gone: a colonial-era cook makes a Dutch taart (butter cake) batter. Some extra eggs are on hand, so in they go – has she not seen Portuguese cooks do likewise to make their cakes richer, softer, more velvety? Familiar with European cakes baked in separate layers and then assembled, she wonders if the layers could be baked in situ instead, just as her Chinese neighbours steam their cakes, and what if that uprising steam was replaced by coal heat radiating from above? And then, surrounded by – or maybe only dreaming of – the East Indies, she seizes on spices from that corner of the empire, those seeds and bark and buds whose aromas lift the spirits. Should these infuse all the batter? Or only half of it, for layers that alternate colours and scents? She thinks and experiments, and so it goes.

Imagine such a narrative, writ not by a single person over an afternoon, but by numberless cooks and bakers, exchanging ideas and handing down legacies through the generations as they spread and grill and press and brush. Is this line of thought and practice not destined to birth something marvellous, something enduringly delicious? As The Straits Times opined in a 1957 article about making spiku (another nickname for spekkoek) for Hari Raya: “The results are more than equal to those achieved by even the most accomplished pastrycook of Vienna.”41

I could not agree more. If mindfully made, each spice-flecked strata should be a beautiful paradox: coherent enough to peel off without tearing, yet thin and fragile enough to melt on the tongue; dairy-lush and spice-opulent, but debonair and delicate, and never ponderous.

Having taken over lapis-making duties from my elders, I understand more keenly why this kueh and its kin have enjoyed such longevity and such exalted status. Refining and notating my family’s lapis legit recipe for my book, The Way of Kueh,42 took me months of research and testing, over 1,300 words and finally three pages of text and photos to do it full justice. Yes, lapis legit and spekkoek require significant mental and physical investment, but when they are imbued with care and commitment, their glory – and the accompanying feeling of achievement – transcends every ounce of expended effort. Master this cake, and you can truly say you have earned your stripes.

Christopher Tan’s book, The Way of Kueh: Savouring & Saving Singapore’s Heritage Desserts (2019), won Book of the Year at the 2020 Singapore Book Awards and was also the winner in the Best Illustrated Non-Fiction Title category. The book is available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries (Call nos.: RSING 641.595957 TAN and SING 641.595957 TAN). It also retails at major bookshops in Singapore.

Christopher Tan’s book, The Way of Kueh: Savouring & Saving Singapore’s Heritage Desserts (2019), won Book of the Year at the 2020 Singapore Book Awards and was also the winner in the Best Illustrated Non-Fiction Title category. The book is available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries (Call nos.: RSING 641.595957 TAN and SING 641.595957 TAN). It also retails at major bookshops in Singapore.

Christopher Tan is a food writer, author, cooking instructor and photographer whose latest book is the award-winning The Way of Kueh, a comprehensive work about Singapore’s kueh culture.

Christopher Tan is a food writer, author, cooking instructor and photographer whose latest book is the award-winning The Way of Kueh, a comprehensive work about Singapore’s kueh culture.

NOTES

-

Throughout this article, I have used different spellings for the word kuih, as appropriate to that community to whose desserts I am referring: hence kuih for Malay items, kueh for Peranakan items, and kue for Indonesian items, plus idiosyncratic spelling within direct quotes. Legit, pronounced with a hard “g”, means “sweet” or “sticky” in Bahasa Indonesia. ↩

-

Personal communication with Kevindra Soemantri (www.feastin.id), 23–30 March, 2019. ↩

-

Pamudji, D. (1986). Hidangan ringan: Party snacks. Kuala Lumpur: Arenabuku Sdn Bhd. (Not available in NLB holdings). Among the author’s lapis recipes are a few with “tikar” designs, constructed by rotating and reassembling cut sections of lapis, to yield complex patterns when sliced across. These pre-date by over a decade the more colourful lapis designs popular in Sarawak. ↩

-

Manden, A.C. (1895). Recepten van de Haagsche kookschool [Recipes from the Hague Cooking School] (p. 244). The Hague: De Gebroeders van Cleef. (Not available in NLB holdings). Founded in the late 1800s, the school provided its female students with formal culinary training. ↩

-

Van der Meijden, J.M.J.C. (1925). Groot nieuw volledig Oost-Indisch kookboek [Great new complete East Indies cookbook] (pp. 305–306). Malang: G.C.T. Van Dorp & Co. (Not available in NLB holdings). A mammoth book chronicling nearly 1,400 recipes from the Dutch East Indies, written to help familiarise Dutch cooks with the cuisine. ↩

-

Also known as red rice, this is rice inoculated with a yeast strain that produces a vivid red pigment as it grows. The dried grains are a traditional Chinese ingredient used to make rice wine and to add colour to dishes. ↩

-

Personal communication with Kevindra Soemantri (www.feastin.id), 23–30 March, 2019. ↩

-

Van der Meijden, 1925, p. 305. ↩

-

Freshly churned butter is always washed with plain water to remove all traces of buttermilk – the liquid separated from the butterfat by the churning – and casein dairy proteins. If not washed away, these make the butter develop rancid off-flavours and turn bad. ↩

-

See note 6. ↩

-

The batters are mixed in the pots so presumably the bowls are used for beating the egg whites. ↩

-

Small brooms – bundled plant stalks or twigs – were historically used to beat liquid ingredients. Metal whisks only started to become more common around the early 20th century. ↩

-

Brooms are not very efficient whisks. ↩

-

Presumably this means a thick and creamy foam. ↩

-

And presumably do the same for the remaining 14 whites for the 14-yolk batter lot, although the recipe does not spell this out. ↩

-

Springform pans with latched sides and removable bases were largely the same then as they still are now. Pan size is unmentioned, so this was either standard knowledge, or the reader is expected to know how to make do. ↩

-

The muslin prevents the cake layer from sticking to your hand as you flatten it. ↩

-

The layering alternates the two batters; every layer is pressed and butter-brushed. ↩

-

The needle test checks for uncooked batter under the surface: heat sources were not always even. The baking set-up is not detailed, but it would have featured top-down heat. ↩

-

Cornelia, N. (1859). Kokki bitja [Beloved cook] (p. 160). Batavia: Lange & Co. (Not available in NLB holdings). Written in Indonesian, this book includes both traditional Indonesian and Dutch recipes. ↩

-

Oost-Indisch kookboek [East Indies cookbook] (pp. 62, 89). (1870). Semarang: Van Dorp & Co. (Not available in NLB holdings). The first Dutch-language cookbook of Indonesian recipes. ↩

-

Koopmans-Gorter, A., & De Boer-De Jonge, G.A.M. (1925). Het nieuwe kookboek [The new cookbook] (p. 307). Groningen: P. Noordhoff. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Delicacies and titbits for Hari Raya. (1983, July 5). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Keasberry, J. (2019, February 25). Spekkoek and kue lapis legit differences revealed. Retrieved from Cooking with Keasberry website. ↩

-

Sitti Nur Zainuddin-Moro. (1980). Kue-kue manasuka [Kue you will like] (pp. 130, 132). Jakarta: Dian Rakyat. (Call no.: RSEA 641.5 ZAI). The author, a cooking academy veteran, formidably marshals 272 recipes for Indonesian kue, colonial delicacies, Western-style cakes, savoury snacks and pantry essentials. ↩

-

Hing, S. (1956). In a Malayan kitchen (pp. 65–66). Singapore: Mun Seong Press. (Call no.: RCLOS 641.59595 HIN). A wonderfully eclectic treasure trove of recipes spanning Indonesian, Malay, Chinese, Dutch and colonial “fusion” items. ↩

-

Prelude to New Year. (1957, January 24). The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Kueh bangket kelapa dan lapis betawi, waduh, lazat sa-kali! (1968, June 2). Berita Harian, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. This recipe has a truly decadent butter-to-flour ratio of around 6:1. ↩

-

Feast with the experts. (1981, January 29). New Nation, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. The name Speckok Kueh Lapis Batavia comes from Mrs Leong Yee Soo’s classic local cookbook, Singaporean Cooking. See Leong, Y.S. (1976). Singaporean cooking. Singapore: Eastern Universities Press Sdn Bhd. (Call no.: RSING 641.595957 LEO) ↩

-

Hari Raya delight for you to try. (1977, September 13). The Straits Times, p. 34. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. “Mascovrish” is likely a rendering of “moscovis”, a Dutch colonial-era name attached to cakes made with dried fruit or candied peel. “Moscovis” refers to Russia, although the connection to the country is unclear. ↩

-

Chefs of S’pore–3. (1950, April 27). The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Fritz Hahn: The Baumkuchen family. (2017). Retrieved from settinger.net website. ↩

-

Personal communication with Kevindra Soemantri (www.feastin.id), 23–30 March, 2019. ↩

-

Keijner, W.C. (1972). Kookboek voor Hollandse, Chinese en Indonesische derechten [Cookbook for Dutch, Chinese and Indonesian dishes] (p. 161). Amsterdam: Uitgeverij J. F. Duwaer & Zonenmsterdam. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Sitti Nur Zainuddin-Moro, 1980, p. 18. ↩

-

Personal communication with Kevindra Soemantri (www.feastin.id), 23–30 March, 2019. ↩

-

Rudy, G. (2020). 23 resep kue autentik Palembang [23 authentic Palembang cake recipes]. Jakarta: Kompas Gramedia. (Not available in NLB holdings). Nine kinds of Palembang lapis are pictured on this book’s cover. ↩

-

Doctor, V. (2019, March 25). Tried bebinca yet? The Goan queen of desserts packs layers of flavour and history. Retrieved from The Economic Times website. ↩

-

Personal communication with Janet P. Boileau (www.janetboileau.com), October 2008. ↩

-

Braga-Blake, M., Ebert-Oehlers, A., & Pereira, A.A. (2017). Singapore Eurasians: Memories, hopes and dreams (p. 246). Singapore: World Scientific. (Call no.: RSING 305.80095957 SIN) ↩

-

Malay women are very busy now. (1957, April 30). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tan, C. (2019). The way of kueh: Savouring & saving Singapore’s heritage desserts. Singapore: Epigram Books. (Call no.: RSING 641.595957 TAN) ↩