Ishak Ahmad and the Story of Malayan Waters

As a senior officer in the Fisheries Department, Ishak Ahmad was instrumental in spurring the growth of the Malayan fishing industry. Anthony Medrano sheds light on his contributions.

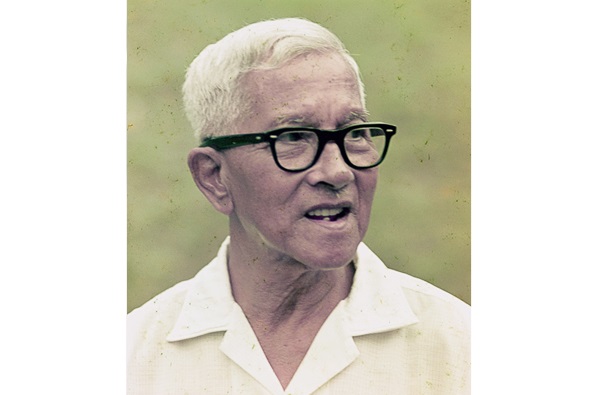

Ishak Ahmad, 1960s. A senior officer in the Fisheries Department, he was also the father of the first president of Singapore, Yusof Ishak. Yusof Ishak Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Ishak Ahmad, 1960s. A senior officer in the Fisheries Department, he was also the father of the first president of Singapore, Yusof Ishak. Yusof Ishak Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Most people in Singapore know of Yusof Ishak, the former journalist and politician who became the country’s first president. However, less well known is the fact that his civil servant father, Ishak Ahmad, was also a significant figure in the history of Singapore and Malaya.

Ishak spent 27 years in the Fisheries Department and worked his way up to its highest rungs. His service was duly recognised when he was awarded the Medal of the Civil Division of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire in 1939.1

However, it was perhaps his work on behalf of the fishermen of Singapore and Malaya that he is best remembered for. During his long career with the Fisheries Department, Ishak acquired a vast knowledge of the many kinds of fish found in Malayan waters and this information helped the government understand where and when economically important species could be found. He was also passionate about helping local fishermen, and did so both directly and indirectly. In fact, at a 1939 event honouring him after he had been awarded the medal, Ishak described himself as a “servant of the public, particularly that public which comprised the fishermen”.2

Ishak’s knowledge of Malayan fishes and their habitats – and the economic lives that both supported – played a key role in shaping the process of urban and social change in interwar Singapore and Malaya. And the legacy of Ishak’s biodiversity knowledge has figured prominently in the publication of important environmental works such as An Introduction to the Sea Fishes of Malaya (1959).3

Ishak Ahmad (left) with his son, Yusof Ishak, the first president of Singapore, 1960s. Yusof Ishak Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Ishak Ahmad (left) with his son, Yusof Ishak, the first president of Singapore, 1960s. Yusof Ishak Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Malaya’s Edible Ocean

Fish consumed as food powered the rise of urban Singapore, with the surrounding seas, reefs and estuaries feeding Malaya’s economic transformation and its concurrent environmental and demographic changes from the late 19th century to the end of the interwar period. For the nearly 30 million Indian and Chinese workers who came to Singapore and the region to tap rubber, extract tin, move cargo in and out of ports, open shops and ply the streets, fish was an essential source of protein.4 Seafood was also a major component of the local Malay community’s daily meal, with products such as ikan bilis (anchovy) and belachan (shrimp paste) crucial ingredients in many home-cooked dishes.

Local fishermen, primarily Malay, were initially the main people involved in catching this important protein but during the interwar years, these fishermen began to come under pressure from Japanese competition.

1926 was a pivotal year that impacted the livelihoods of local fishermen. That year, severe weather made for a poor fish harvest. In one weekend in July alone, six typhoons were reported to have passed through the South China Sea.5 Heavy monsoon rains also restricted the number of days local fishermen could go out to their kelong, the traditional fishing method practised by most fishermen at the time. This created a crisis in the supply of fish, impacting the livelihoods of communities across Malaya. These fishermen suffered economically, physically and materially through the loss or damage to their fishing apparatus such as the stakes and platforms.6

Fishermen working on a kelong, 1951. A kelong is an offshore platform built mainly of wood and driven into the sea bed using wooden piles. Local fishermen use kelong to fish. Bigger ones may also function as dwellings for their families. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Fishermen working on a kelong, 1951. A kelong is an offshore platform built mainly of wood and driven into the sea bed using wooden piles. Local fishermen use kelong to fish. Bigger ones may also function as dwellings for their families. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Okinawan Fishermen in Malaya

The impact of the fish shortage would have been far worse had it not been for one group: the Okinawan fishermen in Malaya. In the early decades of the 20th century, Japan began making inroads into the fishing industry in Southeast Asia to relieve overpopulation in the country’s fishing villages as well as to tap on the Southeast Asian market for marine products.7

The Japanese fishing community in Singapore was largely comprised of young men from the town of Itoman on the island of Okinawa. These Okinawan fishermen had been migrating to Singapore since 1921 to work in the fisheries here.8 By 1926, there were 292 Okinawan fishermen registered in Singapore, making up more than half of the fishing community of 411 Japanese fishermen here.9 These Okinawan Japanese fishermen represented a minute percentage of the entire fishermen population in Malaya, yet it was this group that made up the greatest impact in the fishing scene.10

The Okinawan fishermen had certain advantages over the local fishing community. They used cold storage, had motorboats and deployed an Okinawan fishing method known as muro ami.11 While the combination of refrigeration and diesel engines certainly allowed this small but critical group to fish further from shore and keep larger catches fresh for local markets, it was the introduction of muro ami to Malayan seas that transformed the fishing industry in interwar Singapore and beyond. Indeed, muro ami fishing was one of the main factors that led to Malaya’s boom in the 1920s and 30s, with Okinawan fishermen becoming the dominant suppliers of fresh fish to both urban and rural markets.12

The Japanese muro ami fishing method revolutionised the capture of fish in Malayan waters. A type of reef fish called ikan delah (Caesio spp.), which had been quite expensive to purchase, became a cheap and abundant source of protein. Photo by BEDO. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

The Japanese muro ami fishing method revolutionised the capture of fish in Malayan waters. A type of reef fish called ikan delah (Caesio spp.), which had been quite expensive to purchase, became a cheap and abundant source of protein. Photo by BEDO. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Muro ami fishing revolutionised the capture of fish in and around Malayan waters. Ecologically, this new fishing method targeted offshore coral reefs, a zone of the ocean that had previously been untouched by local fishermen. Economically, it exploited a type of reef fish called ikan delah (Caesio spp.) that was quite expensive to purchase and rarely found in local markets.13

After the advent of muro ami fishing, though, ikan delah became a cheap and abundant source of protein, constituting about 30 percent of the total weight of fish sold in Singapore in 1928.14 By the late 1930s, this share accounted for more than 50 percent.15

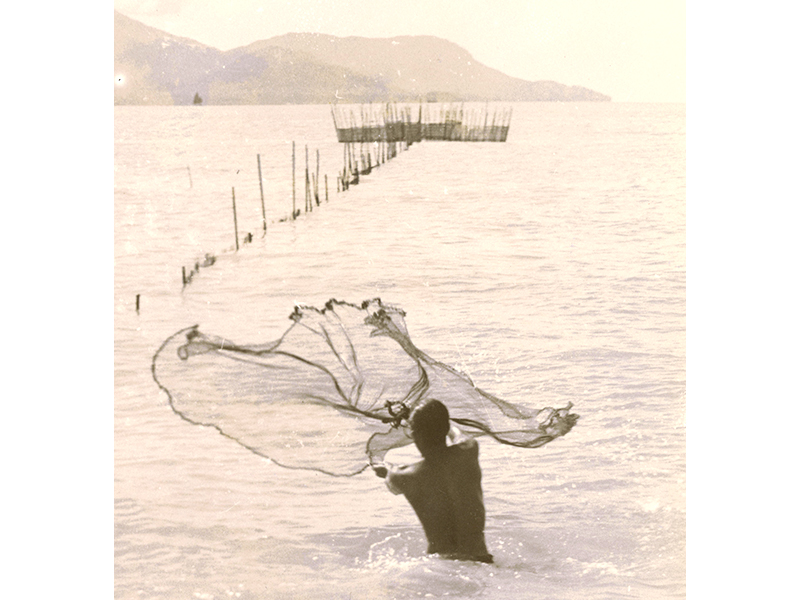

Japanese fishing companies began contributing to the supply of fish in Malaya. By the 1930s, for example, it was estimated that Japanese companies controlled more than 50 percent of Singapore’s fish supply.16 On seeing how these Okinawan fishermen and their operations upended the livelihoods of local fishermen, Ishak saw an opportunity to help them.

A Malay fisherman casting his net, 1954. By the 1930s, it was estimated that Japanese companies controlled more than 50 percent of the fish supply in Singapore, threatening the livelihoods of local fishermen. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A Malay fisherman casting his net, 1954. By the 1930s, it was estimated that Japanese companies controlled more than 50 percent of the fish supply in Singapore, threatening the livelihoods of local fishermen. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

From Kuala Trong to Singapore

Born in 1887 in Kuala Trong, Perak, a mangrove-rich estuarine village north of Kuala Lumpur and about 15 km from the Chinese mining town of Taiping, Ishak entered the colonial government service as a Malay Clerk in the District Office in Taiping in 1906 before joining the Fisheries Department in 1914.17

Growing up by a river in Kuala Trong, Ishak became deeply anchored in a world of fish and water. He understood the ways in which this estuarine ecology supported the economic life of Malays, from providing food to facilitating trade. Similarly, he likely witnessed how upstream changes affected Kuala Trong’s fish supply and impacted the communities that depended on the river’s aquatic life for food and commerce.

As early as the 1890s, Malaya’s rubber boom was transforming Perak. Among other things, this commodity expanded the reach of colonial development. New roads were built, new rail tracks were laid, forests were cleared and migrants were recruited to work on newly planted rubber estates. At the same time, Perak’s tin industry was on the rise but so was the runoff that flowed from the mines around Larung and Matang downstream into the waters near Kuala Trong.18 Ishak came to see how fish was not only the heartbeat of Malay life – because they were free to catch and abundant – but also how their availability could change and, in the process, jeopardise the livelihoods of residents in places such as Kuala Trong.

In 1923, Ishak and his young family moved from Perak to Singapore, where he was appointed as a Senior Fishery Officer with the Fisheries Department. This relocation would prove transformative, both in terms of Ishak’s career and his political work. It also meant new opportunities for his children. For Ishak, however, the question of Singapore’s fish supply loomed large because it was increasingly unclear how local fishermen were to figure within Malaya’s rapidly changing protein economy.

Interwar Singapore was a city on the move, a city on the rise. But at the heart of these urban and demographic changes was an island society wholly dependent on the mass provision of fish. In 1900, Singapore’s population was 228,000. By 1940, this figure had grown to 680,000, making Singapore the second largest city in terms of population in Southeast Asia, behind Bangkok. Critical to feeding the hungry city were the Japanese fishermen, more specifically the Okinawans, who controlled Malaya’s supply of fresh sea fish. The head of this expatriate fishing community was Tora Eifuku, a scientist who had arrived in Singapore in 1914 as part of a Japanese fisheries expedition that sought not only to survey the food potential of Malayan waters, but also to establish Japanese fishing companies in the colonial port city.

The survey itself was completed two years later (1916), and while the government team returned to Japan, Eifuku remained in Singapore to launch his own fishing company. By 1926, he was operating a transregional network of muro ami fleets, ice factories and refrigeration plants.19

Comprised largely of Okinawan fisherman, Eifuku’s operations Taichong Kongsi was the largest fishing company registered in interwar Singapore at the time.20 While Chinese fishmongers controlled the distribution of fish through a network of stalls, buyers and vendors, it was Eifuku and other Japanese companies that provided the majority of the fresh fish in Singapore. In addition, a combination of lorries and rails linked Okinawan-caught fish (packed on Japanese-made ice) to the rubber plantations, Malay markets, and the tin and iron mines of interior Malaya.21

The combination of scale, mobility, capital and technology enabled Eifuku’s cartel, and other Japanese companies like his, to dominate the late interwar supply of fish in Singapore and Malaya. This squeezed out the local fishing communities, who were unable to compete with the Okinawan fishermen in terms of freshness, quantity and price. Losing out to the Japanese was a huge blow as it affected their livelihoods.22

Partly in response to the plight of these fishermen and their dislocation within Singapore and Malaya’s changing fishing economy, Ishak decided to become politically involved. After moving to Singapore in 1923, he became a founding member of the Kesatuan Melayu Singapura (KMS; Singapore Malay Union), the colony’s first Malay political association and established in 1926.23

KMS was led by Mohamed Eunos bin Abdullah, a one-time harbourmaster and postmaster who became the organisation’s first president as well as the founding editor of Utusan Melayu, Singapore’s first daily Malay-language newspaper. The association sought to advance the interests of the local Malay community.24 For Ishak, KMS was an important platform. It enabled him to communicate his concerns about the uncertain future of local fishermen as well as why their livelihood was at stake.

Knowing Malayan Waters

Ishak’s knowledge of Malayan seas and the promise these waters held for the economic life of Malaya was especially deepened through his work with the Fisheries Department in the 1920s and 30s. During this period, Ishak conducted biological surveys off Pulau Tioman, tuna experiments in Terengganu and kelong inspections around Pulau Ketam, off the coast of Selangor, among other activities. In Singapore, he participated in a Malay-language radio programme that championed Malaya’s edible ocean.25

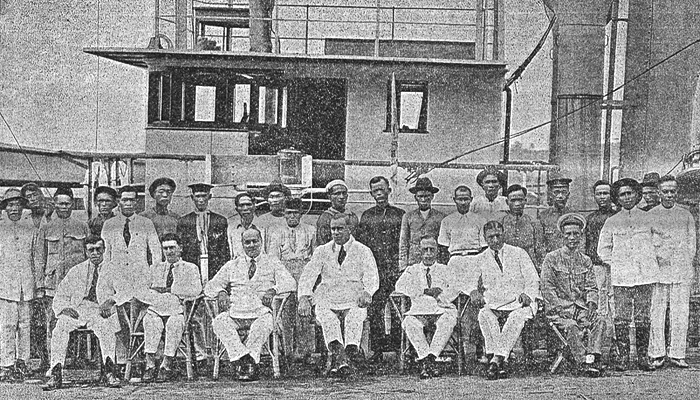

In 1926, Ishak played an important role in the first survey expedition conducted by the Fisheries Department to explore, map and index the economic fauna of Malayan waters.26 At the centre of these scientific investigations was the S.T. Tongkol, a coal-powered steamer built to search and identify suitable fishing grounds and to test the use of European trawls.

Ishak served a vital scientific as well as economic role in the expedition.27 As the only Malay member, the combination of his linguistic skills (he also spoke Hokkien and Teochew), cultural expertise and knowledge allowed him to translate (or approximate) the species of fish caught in vernacular terms. While other members of the S.T. Tongkol were concerned with technical and technological matters, such as the efficacy of European trawls in Malayan seas, Ishak was the expedition’s official taxonomiser.

Crew of the S.T. Tongkol. Ishak Ahmad (in white top and black hat) is standing second from the right. The coal-powered steamer was used to search and identify suitable fishing grounds in the first survey expedition conducted by the Fisheries Department in 1926. Accessed at the National Archives of Malaysia.

Crew of the S.T. Tongkol. Ishak Ahmad (in white top and black hat) is standing second from the right. The coal-powered steamer was used to search and identify suitable fishing grounds in the first survey expedition conducted by the Fisheries Department in 1926. Accessed at the National Archives of Malaysia.

His focus was on “making sense” of the ocean’s marine products in ways that rendered them familiar to Malay and non-Malay speakers alike.28 As a result, Ishak produced the Malay names of more than 75 fish species.29 In doing so, he brought a vernacular sensibility that only a local could achieve in the creation of modern taxonomic records. In the case of the Jewfish (a class of groupers), for instance, he identified three types commonly known to Malays: Gelama tikus, Gelama panjang and Gelama pisang.30

Knowing a fish’s name in Malay (and whether it was poisonous or not) was crucial to fitting the species within the local food supply and marketing it on land.31 In this way, Ishak’s scientific work had real economic implications for both the S.T. Tongkol and Singapore’s Clyde Terrace Market on Beach Road, the expedition’s main distribution point for its caught fish. From this central market, city officers operated a year-round public auction. Buyers included stallholders from Clyde Terrace and other local fish markets, contractors supplying ocean liners and cargo ships, and Singapore’s first supermarket, Cold Storage.32

Through the public auction, boxes of edible fish – weighed and identified by their Malay names – were sold and distributed throughout Malaya. On average, 17 tons of fish were sold per day at Singapore’s various fish markets. From late May to late December in 1926, the S.T. Tongkol landed almost 200,000 pounds of food fish, netting – through the public auction system – a tidy sum of nearly $30,000.33 Ishak’s Malay names for the various types of fish – rather than their English approximations such as smelt, herring, perch, sole or grunter – facilitated the marketing and dispensing of the fish supply caught by the S.T. Tongkol.

In the end, as it turned out, the surrounding seafloor’s abundance of mud, sea-fans, sponges, corals and especially seagrass rendered Malayan waters resistant to European trawls, leading to a fiscal loss and the eventual sale of the S.T. Tongkol to the government in Ceylon in 1929.34

On the whole, however, the Tongkol expedition was invaluable as it developed a scientific understanding of Malayan waters and the fishes that were indigenous to these waters. Economically important to this new understanding was knowing where Malayan fishes thrived in terms of their preferred habitats (ecology) and preferred depths (bathymetry) as well as when these economic species were abundant (in terms of their preferred seasons). Harnessed by Ishak and others in the Malayan Fisheries Department, the scientific data derived from the Tongkol expedition in the late 1920s was used to strengthen the local fishing industry and therefore boost the local fish supply.

Ishak’s Legacy

The late interwar period was a pivotal time. In 1933, Ishak was appointed to act as Director of Fisheries when the incumbent W. Birtwistle was on leave for eight months.35 As acting Director, Ishak was in charge of a colonial service that recognised the strategic food value of Malayan waters as well as how fish supplies were needed – and increasingly so – without disruption and delay. From his experience on the ground, Ishak also knew that the Malayan system of producing, marketing and distributing fish depended heavily on the work of Japanese companies and the Okinawan fishermen they employed, and how this impacted the Chinese, Malay and Indian fishermen in Singapore.

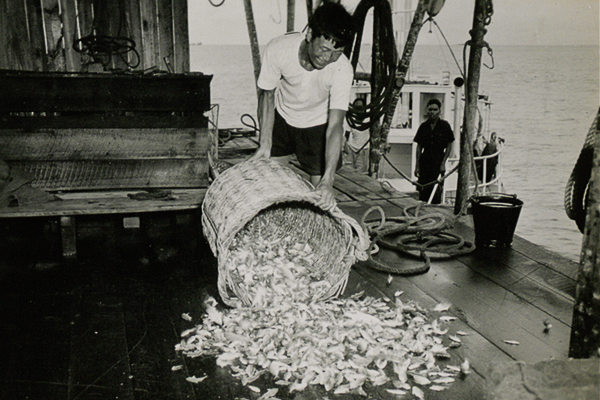

Ishak extended government assistance to local fishing communities, thereby aiding them to tap the wealth of Malayan seas to feed the growth of cities like Singapore. In 1937, for example, he sought to offset the dominance of Japanese-caught fish by refitting the department’s experimental vessel, Kembong, with an on-board refrigeration plant so that it could transport fresh fish supplies from Terengganu and Kelantan to Singapore.36 By improving access to distant hungry markets, Ishak was boosting the livelihoods of Malaya’s east coast fishing communities. He extended similar refrigeration schemes to Chinese fishermen who worked the Strait of Melaka, particularly around Pulau Pangkor.

A Chinese fisherman with his catch, 1951. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

A Chinese fisherman with his catch, 1951. Ministry of Information and the Arts Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

As a result of his distinguished career in public service, including two stints as acting Director of Fisheries, Ishak was awarded the Malayan Coronation Medal in 193737 and the Medal of the Civil Division of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire in 1939. With more than 100 people in attendance, including a popular Malay musical orchestra, the KMS hosted an afternoon tea celebration at the Kota Raja Malay School in February 1939 in recognition of Ishak’s service to Singapore and Malaya.38

That same year, Ishak played a central role in establishing Malaya’s first fisheries school in Tanah Merah that, among other things, sought to “modernise” traditional fishing methods and equip local fishermen with new technology and knowledge.39 Likewise, he founded a Malay school for the children of Pulau Sudong’s fishing community.40 After a long and decorated career, Ishak retired from the Fisheries Department in 1941.

Ishak Ahmad founded a Malay school on Pulau Sudong for the children of the island’s fishing community. It was opened in 1940. The Straits Times, 26 March 1940, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Ishak Ahmad founded a Malay school on Pulau Sudong for the children of the island’s fishing community. It was opened in 1940. The Straits Times, 26 March 1940, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

But even in retirement, Ishak’s life remained intertwined with the story of Malayan waters. A closer look at the year 1959 reveals this intimate connection. In that year, Ishak’s eldest son, Yusof, was appointed Yang di-Pertuan Negara (Head of State) after Singapore was granted internal self-government. Another son, Abdul Aziz, who once worked in the Fisheries Department before the war, was the Federation of Malaya’s first Minister for Agriculture, a post he held from 1955 to 1963. As minister, Abdul Aziz oversaw the management of inshore and offshore fisheries – much like his father did in the 1930s.

It was under Abdul Aziz that the Ministry of Agriculture published An Introduction to the Sea Fishes of Malaya (1959). This publication recognised Ishak’s “wealth of knowledge and experience” as a cultural and scientific repository borne from his lifelong association with Malayan waters. Prior to its publication, Ishak had “consented to examine the manuscript and made many valuable comments which have been incorporated in the finished work” as the foreword notes.41

From cataloguing the fish diversity of Malayan seas as a scientific member of the Tongkol expedition in the 1920s to sharing his wealth of knowledge and experience with a global community of ichthyologists in the 1950s, Ishak’s life and contributions are critical to appreciating how we know what we know about the waters around us today.

Assistant Professor Anthony Medrano is the National University of Singapore Presidential Young Professor of Environmental Studies at Yale-NUS College. He is a former Ziff Environmental Fellow at Harvard University and has a PhD in History from the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Assistant Professor Anthony Medrano is the National University of Singapore Presidential Young Professor of Environmental Studies at Yale-NUS College. He is a former Ziff Environmental Fellow at Harvard University and has a PhD in History from the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

NOTES

-

Award of the Medal of the Civil Division of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire to the undermentioned: For Meritorious Service. (1939, January 2). Supplement to the London Gazette, p. 20. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Malay who speaks two Chinese dialects honoured. (1939, February 20). The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Scott, J.S. (1959). An introduction to the sea fishes of Malaya (p. iii). Kuala Lumpur: Ministry of Agriculture. (Call no.: RCLOS 597.925 SCO) ↩

-

For the scale of migration in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, see Amrith, S.S. (2011). Migration and diaspora in modern Asia (pp. 18–19). Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press. (Call no.: R 304.8095 AMR) ↩

-

Shipping notes. (1926, July 20). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Governor Hugh Clifford to Members of the Legislative Council. (1927, October 10). (Reference no.: CO 273/537/24). Retrieved from The National Archives UK website. ↩

-

Chen, H. (2008, June 1). Japan and the birth of Takao’s fisheries in Nanyo 1895–1945. International Journal of Maritime History, 20 (1), 133–152. Retrieved from SAGE Journals website. ↩

-

For references to Okinawan fishermen in Southeast Asia, see De Indische Courant, 25 November 1925, p. 2; Het Vaderland, 25 December 1929, p. 8; De Sumatra Post, 1 December 1925, p. 5; and Markus, B. (1930–1941). De Japansche visscherij in het Oosten van de Archipel (p. 2). Batavia: Instituut voor de Zeevisscherij. (Not available in NLB holdings). In the 1920s, Okinawans, mostly from Itoman, also went to work the waters around Saipan, Palau and the Marianas. See Higuchi, W. (2007). Pre-war Japanese fisheries in Micronesia: Focusing on bonito and tuna fishing in the Northern Mariana Islands. Immigration Studies, (3), 49–68, p. 51. For a close analysis of the relationship between Itoman and Singapore, see Shimizu, H. (2008, June). Theories of migration and the Okinawan fishermen in colonial Singapore. Research on Contemporary Society, (3), 27–42, pp. 27, 34. Retrieved from Aichi Shukutoku University website. ↩

-

Hiroshi, S. (1997, September). The Japanese fisheries based in Singapore, 1892–1945. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 28 (2), 324–344, p. 329. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. Hiroshi uses the Japanese Foreign Ministry Archives, J1.2.0, 1927, to reconstruct the number of Okinawans in Singapore. ↩

-

Governor Hugh Clifford to Members of the Legislative Council, 10 Oct 1927. ↩

-

“Muro Ami”. (1926, September 4). The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

For Singapore and Penang, see the Annual report on the Colony of the Straits Settlements for the year 1927 in CO 273/552/17, The National Archives UK; for Batavia, see Delsman, H.C. (1939, February). Fishing and fish-culture in the Netherlands Indies. Bulletin of the Colonial Institute of Amsterdam, 2 (2), 92–105; and for Manila, see Herre, A.W., Miscellaneous Notes, Box Folder: 2, Series: Notes III, Dates: 1929–1948. Accessed at Albert W. Herre Papers, Special Collections, Western Libraries Heritage Resources, Western Washington University. ↩

-

Report on the Tongkol. (1928, July 7). The Straits Times, p. 3; Notes of the day: Local fisheries. (1929, May 21). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore’s fish supply. (1928, May 14). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 14 May 1928, p. 3. ↩

-

Japanese fishermen may not get renewals of licences. (1938, June 29). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

In Malay, kuala means “estuary”. For information about Kuala Trong and the Matang mangrove reserve, see Mohammad Ismail Shaharuddin et al., (Eds.). (2005). Sustainable management of matang mangroves 100 years and beyond. Kuala Lumpur: Malaysian Forestry Department. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Abdul Aziz Ishak. (1983). Mencari bako (p. 27). Kuala Lumpur: Penerbitan Abadi. (Call no.: Malay RSEA 079.5950924 ABD) ↩

-

For Tora Eifuku’s work in the Dutch East Indies (also known as Netherlands Indies), see De Japansche Visscherij. (1925, November 25). Bataviaasch Nieuwsblad, 1; Het Visscherijbedrijft te Soerabaja. (1926, September 9). De Sumatra Post, 5; De ‘Fuku Maru’. (1938, January 7). Het Nieuws Van Den Dag Voor Nederlandsch-Indie, 2. For his operations in the Gulf of Martaban, Burma, see Mystery move by Japanese. (1938, December 11). The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. In 1936, Eifuku applied for a licence to fish in the Mergui Archipelago, but he had already been operating there for several years. See National Archives of Myanmar. (1936–1937). Fishery by Japanese in the Mergui Archipelago. (Accession no. 1266, series 1/7, file IV–8); On his offices in Penang, Batavia and Singapore, see De Japansche Visscherij. (1925, December 1). De Sumatra Post, 5. ↩

-

The Malayan Bulletin of Political Intelligence. (1925, June). (Reference no.: CO 537/933/4). Accessed at the National Archives of Singapore. ↩

-

Malaya cannot supply her own requirements of fish. (1934, August 30). The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Agricultural progress in the colony. (1937, September 3). The Malaya Tribune, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Parti Melayu lahir di Istana Kg Glam. (1985, April 9). Berita Harian, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The British appointed Mohamed Eunos bin Abdullah to the Straits Settlements Legislative Council in 1924, making him the first Malay to serve on the council. Eunos remains a fixture within Singapore’s political history. As a member of the Legislative Council, he voted against the establishment of a public aquarium in the 1930s. ↩

-

Page 21 Miscellaneous Column 2: Programme of B.M.B.C. (1937, May 10). Morning Tribune, p. 21. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

National Archives of Malaysia (NAM). (1926, May 28–31 December). Report on the Working of the S.T. ‘Tongkol’. (Selangor Secretariat (SS), 3182/1927). The colonial government in Indochina also conducted a series of trawling expeditions in the South China Sea from 1925 to 1929. See Chevey, P. (1932). Poissons des campagnes du “de Lanessan” (1925–1929). Travaux de l’Institut océanographique de l’Indochine, 4, 1–155. ↩

-

National Archives of Malaysia (NAM), 28 May–31 Dec 1926. ↩

-

On “making sense” as a cultural process of knowing in Southeast Asian history and studies, see Wolters, O.W. (1994, October). Southeast Asia as a Southeast Asian field of study. Indonesia, (58), 1–17. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

In post-war Malaya, Ishak was often consulted by fish experts for his “wealth of knowledge”. For the publication of J.S. Scott’s An Introduction to the Sea Fishes of Malaya in 1959, for instance, Ishak “examine[d] the manuscript and made many valuable comments which [were] incorporated in[to] the finished work”. See Scott, 1959, p. iii. ↩

-

National Archives of Malaysia (NAM), 28 May–31 Dec 1926. Part II, appendix IV, “Scientific Names of Fish Caught by the S.T. ‘Tongkol’.” ↩

-

On poisonous fish as a subject in Southeast Asian ichthyology, see Seale, A. (1912). Poisonous fishes of the Philippine Islands. Bureau of Health Bulletin, No. 9; Herre, A.W.C.T. (1924, October). Poisonous and worthless fishes: An account of the Philippine plectognaths. Philippine Journal of Science, 25 (4), 415–512. Retrieved from Semantic Scholar website; Hiyama, Y. (1943). Report on the research of poisonous fish in the South Seas. Odawara: Nissan Fisheries Institute. (Not available in NLB holdings) (in Japanese). ↩

-

Cold Storage was established in 1903. For more on its history, see Goh, C.B. (2003). Serving Singapore: A hundred years of Cold Storage, 1903–2003. Singapore: Cold Storage Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 381.148095957 GOH) ↩

-

National Archives of Malaysia (NAM), May 28 May–31 Dec 1926. ↩

-

On the idea of nature’s resistance, I am reminded of Frantz Fanon’s important line: “The resistance that forests and swamps present to foreign penetration is the natural ally of the native.” See Fanon, F. (1963). The wretched of the earth (p. 294). New York: Grove Press. (Not available in NLB holdings). On the sale of the S.T. Tongkol, see Ceylon fisheries. (1929, September 10). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. On the abundance of sea grass, see National Archives of Malaysia (NAM), 28 May–31 Dec 1926. Part II, “Biological Aspects of Trawling Experiments”. ↩

-

In 1933, Ishak was appointed as acting Director of Fisheries. See Malay in charge of all Malayan-department. (1937, May 15). The Straits Times, p. 12. Also in 1933, Ishak was elected President of Singapore’s Fathul Karib Club. Founded in 1898, Fathul Karib was a soccer club that competed in all-Malaya tournaments. See Fathol Karib Club. (1933, March 23). The Malaya Tribune, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Malaya’s fishery ‘ice-box’. (1937, July 28). The Straits Times, p. 20. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Malayan Coronation Medal Awards. (1937, May 26). The Straits Times, p. 17. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Tea to fisheries officer. (1939, February 20). The Malaya Tribune, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Singapore school of fisheries opened. (1939, October 6). Morning Tribune, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

On Ishak, the school and Pulau Sudong, see The Straits Times, 20 Feb 1939, p. 12. On KMS and Pulau Sudong, see An island school. (1940, March 26). The Straits Times, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Minutes of the Legislative Council. (1940, October 14). (Reference no.: CO 275/154/147). Retrieved from The National Archives UK website. On Pulau Sudong’s fishing community, see Chew, S.B. (1982). Fishermen in flats. Melbourne: Centre of Southeast Asian Studies, Monash University. (Call no.: RSING 301.4443095957 CHE) ↩