The Nature of Poetry: An Odyssey Across Time

Michelle Heng takes us on a journey to see how poets writing in English have charted the changing contours of Singapore and Malaya over the course of the 20th century.

This print titled “Road Near Selita” (1869) by the Austrian diplomat and naturalist Eugen von Ransonnet was published in his Skizzen aus Singapur and Djohor (Sketches: Singapore and Johor) in 1876. It shows a road in Selita (Seletar), Singapore, as observed by von Ransonnet, who described it as a most attractive road cutting through tropical vegetation. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

This print titled “Road Near Selita” (1869) by the Austrian diplomat and naturalist Eugen von Ransonnet was published in his Skizzen aus Singapur and Djohor (Sketches: Singapore and Johor) in 1876. It shows a road in Selita (Seletar), Singapore, as observed by von Ransonnet, who described it as a most attractive road cutting through tropical vegetation. Courtesy of the National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board.

Some residents of Singapore undoubtedly take the greenery in the city-state for granted, perhaps imagining that the island has always maintained a neat and manicured coiffure, with overgrowth trimmed to precision and denuded of inconvenient fauna.

Many a poet has documented, however, the slew of urban-renewed makeovers that have no doubt contributed to the “Garden City” moniker. Poet-cartographers have captured the many iterations of the landscape’s continuous transformation – physical and otherwise – over the years.1

The motifs explored include a collective memory of Singapore’s (and Malaya’s) flora, fauna, and the deep, almost primal communion humans share with nature – juxtaposed alongside key historical moments as well as tales from the myths and legends enshrouding the island’s origins. These extend to more current dialogues on sustainability, green plans and urban gardening amid changing climes.

In the Beginning: Nature vs Nurture

Literary musings on nature have often been closely intertwined with Singapore’s history.2 The intimate relationship between nature and lyricism is evident at the start of the island’s recorded history in the 17th-century Sulalat al-Salatin (Genealogy of Kings), better known as Sejarah Melayu (Malay Annals). One of the chapters describes the founding of the city of Singapura (Sanskrit for “Lion City”) on the island of Temasek around 1299 by Sang Nila Utama, the mythical prince of Palembang, when he and his attendants caught sight of the singa, or lion, upon their arrival.3 The Sejarah Melayu is one of the most significant Malay historical works, and also hailed as one of the finest literary works written in Malay.4

The development of nature-themed lyrical works continued with literary contributions to various homegrown publications. An early encounter of nature poetry can be traced to the start of the 20th century in a poem titled “Nature’s Secret” by one “Gak-Stok-Sin” that appeared in the December 1907 edition of The Straits Chinese Magazine: A Quarterly Journal of Oriental and Occidental Culture.5 “Nature’s Secret” appears to have mimicked contemporary English poetry of that era with invocations of the wind, the sea and what seems to be a nod to a familiar literary symbol, the willow tree, as seen in the second stanza:6

Winds and waves and willow tree

Pray unveil the mystery,

Of that deep soul-thrilling song

Winding without words along

Which enthralls the sons of men

Though its meaning none can ken.7

It is noteworthy that this poem is one of several literary works appropriating the language of the colonial administrators yet deftly made English its own.8 The poet attempted to “nurture” seemingly untameable forces of nature by artfully “bending” these into a tidy array of lyrical lines. By essaying creative forays in an adopted tongue9 – albeit through some form of mimicry – early poets in the colony charted a new course for later generations of homegrown poet-cartographers.

Clanging Trains Signal Changes to Kampong Idyll

One of the oldest poems written by a homegrown poet, “F.M.S.R.” was published in 1937 by a poet who used the pseudonym “Francis P. Ng”. The influences of Modernism on “F.M.S.R.” are evident in its form and certainly resonates with the dark undertones seen in T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land”.10 Through dogged detective work, researcher Eriko Ogihara-Schuck established that Francis P. Ng was actually Teo Poh Leng, who was born in Singapore in 1912 and who died in 1942 at the start of the Japanese Occupation (1942–45).11

Teo Poh Leng (also known as Francis P. Ng) is in this photo taken of the staff and graduates of Raffles College in 1934. He is unidentifiable to date as no photos of him have been found. Image reproduced from Raffles College Union Magazine, July 1934, Vol. 4, No. 10, between p. 42 and p. 43.

Teo Poh Leng (also known as Francis P. Ng) is in this photo taken of the staff and graduates of Raffles College in 1934. He is unidentifiable to date as no photos of him have been found. Image reproduced from Raffles College Union Magazine, July 1934, Vol. 4, No. 10, between p. 42 and p. 43.

“F.M.S.R.” describes a train journey between Singapore and Kuala Lumpur – operated by the Federated Malay States Railways (FMSR) – and expresses the frustrations of a subject living under British colonial rule. The poem brings to the fore aspects of life in Malaya such as post-World War I privations, and a country struggling to deal with a tide of growing industrialisation and deforestation looming over a previously tranquil landscape. A closer look at these lines hint at his disdain for a homeland that has become a playground for a consumerist society:

Nowadays monarchy and democracy

Are mere appellatives for mediocracy,

So’s the aristocracy

Of wealth: these millionaires,

What numskulls they must be

Who are unawares of their own idiocy.

Unwittingly they come, unobserving see

The same wares they did leave behind at home,

To meet foreign jeers,

To see tigers and snakes in Singapore

And drink Tiger Beers.

But our tigers have grown timorous

And dare not come forth to meet the amorous

Whimsicality of the rich visitor.

So to the Ponggol Zoo she goes

To meet living tigers, snakes and armadilloes:

Or dead tigers guarding garish

advertisement panels;

Or Raffles Museum to stare at stupid animals.12

The tigers and other wild animals that previously roamed the Malayan countryside have not only been defanged and stripped of their potency, they have become symbols of consumerism as a well-known homegrown beer label. In addition, a menagerie of tropical fauna (“living tigers, snakes and armadillos”) have now become mere exhibits at Ponggol Zoo or reduced to lifeless, taxidermied specimens at Raffles Museum for gawking visitors.

Teo’s elaborate use of imagery of lifeless animals continues in Canto VIII as the poet describes how the serpentine locomotive “Dragging its rigid length like a snake/Hissing, wounded in the spine, moving – /Leaving writhing marks of crimson lake: Johore Bahru, Kluang, Gemas…” cuts noisily through a serene, agrarian Malayan landscape presaging much ruin as it pierces through “prostituted jungles” and “imitated tunnels”.13

In a dramatic climax near the end of this long poem, the unnamed narrator alights at Kuala Lumpur and we learn that the train he was just riding in has collided with another in “a terrific smash”, thereby cementing the poet’s notion that:

The world’s the train, a crepitating blaze,

A polluted place,

And all its saints are no less sinners…14

It has been suggested that this climatic scene in Canto IX highlights the destructive effects of British rule,15 and that the poet’s introspection is reflected in the grim picture he paints of Singapore and Malaya in the 1930s. Unwittingly, the poem also foregrounds the tragic days of the Japanese Occupation and the eventual loss of Britain’s Southeast Asian colonies in the following decade.16

Resilience in Times of War

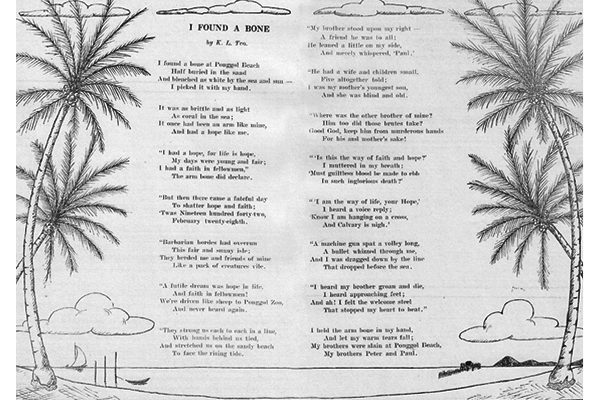

The poet of “F.M.S.R.” is mourned by his brother, Teo Kah Leng, in the 1955 poem “I Found a Bone”. A dramatic poem with a regular rhyme scheme, the poet uses Biblical imagery for his testimony of historical events as seen in the lines below:

I held the arm bone in my hand,

And let “my warm tears fall;

My brothers were slain at Ponggol Beach,

My brothers Peter and Paul.17

Photo of Teo Kah Leng taken in front of Holy Innocents’ English School, late 1940s to early 50s. He wrote “I Found A Bone” in the aftermath of the Japanese Occupation. Courtesy of Anne Teo.

Photo of Teo Kah Leng taken in front of Holy Innocents’ English School, late 1940s to early 50s. He wrote “I Found A Bone” in the aftermath of the Japanese Occupation. Courtesy of Anne Teo.

This haunting poem about a man who finds a fragment of an arm bone on Punggol beach was one of the few clues linking Teo Kah Leng and Teo Poh Leng as siblings and, sadly, confirmed the untimely death of the latter during the Sook Ching massacre at the onset of the Japanese Occupation.18 The poem bears witness to the once pristine seaside village of Punggol (spelt “Ponggol” in the poem) and hints at the leisurely lifestyle that it was once known for.

Coincidentally, the two poems by the Teo siblings both mention Ponggol Zoo, one of the earliest public zoos in Singapore, established in 1928 by wealthy pioneering trader William Lawrence Soma Basapa.19 The following lines from “I Found a Bone” describe in stark detail the brutal massacre site that Punggol beach is later remembered for:

“A futile dream was hope in life,

And faith in fellowmen!

We’re driven like sheep to “Ponggol” Zoo,

And never heard again.

“They strung us each to each in a line,

With hands behind us tied,

And stretched us on the sandy beach

To face the rising tide.20

Teo Kah Leng’s poem, “I Found A Bone”, was published in the Holy Innocents’ English School Annual in 1955. Courtesy of Montfort Schools.

Teo Kah Leng’s poem, “I Found A Bone”, was published in the Holy Innocents’ English School Annual in 1955. Courtesy of Montfort Schools.

The war is also one of the subjects of Lim Thean Soo’s “Lallang”, published in 1953. Here, the poet uses a sharply defined image from nature and explores the common tropical weed’s hardy qualities (now usually spelt lalang), which have weathered both the vagaries of harsh weather and brutal invasions:21

I have breathed since times the granite cooled its temper;

The primal sun scorched me.

I have traced the last oceanic invasion;

The ancient rains soaked me.

Monster herds, human tribes:

Chinese fleets, Malay drums;

European cannons, Samurai swords!

– Did not they appear only yesterday?

And I grew used to war, man’s endless game.

But I am the lallang

Do not ever suffer

No wrong is done to me

I know no misery.22

Written in the aftermath of a dark period in Singapore’s history, the prickly tenacity of the familiar lalang grass registers an emotive appeal to readers here. An unlikely triumph against marauders and invaders, the self-renewing lalang reflects the spirit of a tenacious people who are survivors of war and other turbulent episodes.23

Imagination Comes Alive in “The Cough of Albuquerque”

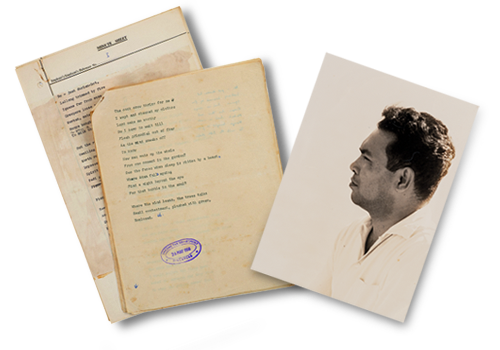

What is arguably the most significant work to prominently feature the local landscape is “The Cough of Albuquerque”, a maiden attempt at writing a long poem by one of Singapore’s best-known pioneer poets, Edwin Thumboo.

Born in Singapore in 1933, Thumboo’s idyllic childhood spent in the foothills of Mandai inspired much of the lush imagery observed in his poem, which was first written in the mid-1950s and revised decades later.24

The “Albuquerque” in the poem refers to Afonso de Albuquerque, commander of the Portuguese forces that captured the Sultanate of Melaka in 1511. The version of Albuquerque in the poem, however, is an old warrior who fantasises about a princess living on Mount Ophir.25

“The Cough of Albuquerque” showcases Thumboo’s youthful vision of forging a new Malayan experience with a forceful interplay of imagery, symbolism and myth-making. He evokes scenes of untamed wilderness found in a pre-independence Malayan landscape shrouded in the mists of homegrown folklore, tales of Western explorer-generals and mythic legends, and “attempts to do for Malayan culture what W.B. Yeats did for Ireland”.26

The poem’s title takes inspiration from the death-in-life imagery invoked by an old man in an arid season as seen in T.S. Eliot’s “Gerontion”. The “Cough” in the poem’s title is an allusion to a line in “Gerontion”: “The goat coughs at night in the field overhead;/Rocks, moss, stonecrop, iron, merds.” The goat, a symbol of white-hot fertility, is brought into sharp relief by the bone-dry sterile wasteland found in the next line.27

Thumboo’s poem is arranged in five sections of 50 to 60 lines each and gives full play to the poet’s weaving of myth, history, images and symbols, as well as philosophy and spirituality in a rich tapestry of individual and collective experiences.

(Above left) In 2006, Edwin Thumboo donated 15 sets of sepia-toned authorial drafts of “The Cough of Albuquerque” to the National Library Board. The typescripts shown here include Thumboo’s handwritten edits. These provide glimpses into the careful and considered pursuit of his craft. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RCLOS 378.12095957 THU-[ET]; Accession no.: B20056083B).

(Above left) In 2006, Edwin Thumboo donated 15 sets of sepia-toned authorial drafts of “The Cough of Albuquerque” to the National Library Board. The typescripts shown here include Thumboo’s handwritten edits. These provide glimpses into the careful and considered pursuit of his craft. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RCLOS 378.12095957 THU-[ET]; Accession no.: B20056083B).(Above right) Portrait of Edwin Thumboo, c. 1958, during the time when he was working at the Income Tax Department. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RCLOS 378.12095957 THU-[ET]; Accession no.: B20056083B).

Alternating between the familiar “durian-hot” environs of the Malayan landscape and the dream-like scenery in mythical places, Thumboo’s keen observations of nature is evident through the “evocation of landscape through a few sharply defined images in nature”.28

In the first section, the subject in the poem takes a lyrical hike, first through a landscape more commonly seen in Western literary traditions, peppered with references to classical mythological figures like “Dido and her pyre”29 and a “Cabalistic eye, old guardian of the door” that if read as “symbols of a colonial inheritance, augur a collapse”.30

As the subject of the poem ventures further on his hike, he encounters imagery more redolent of a tropical Malayan landscape upon which a post-colonial identity might be established. Here, the poet as lyrical cartographer discards the earlier mentions of Greek mythic figures31 and maps a distinctive terrain with descriptions that are immediately recognisable to readers in this part of the world:

No – just durian-hot,

Lallang trimmed by fire.

Iguana far from ooze

Creepers loose their coil

Merbak, mateless on the branch,

Nonya bought her fan

To milk the little shade.32

In Section IV of the poem, the subject proclaims his identity, discards his colonial inheritance and declares a national belonging:33

… This is my country

Before the roots threw grapnel

And I feel the stream from Terbrau near

Chempaka blooms;

There, old tembusu bright with superstition

Now sunlight marching through.

I’ll plant my feet.

The cough of Albuquerque,

Wind stiff with remorse:

A new beginning touch my shoulder.34

Place names such as Terbrau in Johor allude to Singapore’s close relationship with its northern neighbour. Meanwhile, a visitation of sunlight brightens the mood of the poem and brings about a “new beginning” with the dispelling of mythic dangers lurking within the terrain suggested by the imagery of the ancient tembusu trees “bright with superstition”.

Tides of Change

With Singapore’s independence in 1965, the push for development, especially mass resettlement projects that created unfamiliar landscapes and neighbourhoods, gave rise to disquieting responses in homegrown poetry.35 Offering an alternative view to the industrious, purpose-filled atmosphere of a newly independent nation, the late poet-novelist-playwright Goh Poh Seng’s verse chips away at the gleaming facade of this island nation to reveal the rusty scaffold beneath. In his 1976 poem “Singapore”,36 we witness the relentless tides of change that have swept through the country during its nation-building years as the poet laments the tainting of a simpler way of life, now threatened by the allure of commerce:

Towards the sea’s fresh salt

the river bears pollution

whose source was simple hills

Whose migration was tainted

when man decided to dip his hand

Nourishing his wants

a commercial waterway

greased with waste37

Echoing similar sentiments, Arthur Yap’s 1980 poem “Old Tricks for New Houses”38 makes a wry remark on the land reclamation initiatives to develop residential estates:

the sea can’t reach you now

& it’ll be further away next year.

your neighbours will hang crabshells

on their pomegranate plants as saline testimony,

your proximate goodwill will be good

& help salt away the years in happy homes.39

In many of Yap’s poems, the promise of economic success and material gains is often compromised by scenes of stagnation and a sense of alienation.40 The remnants of marine life described in “Old Tricks for New Houses” are left hanging as pomegranate plants lining the corridors of public housing estates – built on reclaimed land – as a mere memory of the natural landscape.

Clean-up Campaigns and Green Plans

The Singapore of today, with its manicured gardens, roadside greenery and tamed landscape, is vastly different from the one that inspired Thumboo and the poets of the immediate post-war period. Today’s poets, are in fact, inspired by the process of mastering nature, as the works in the 2015 anthology From Walden to Woodlands demonstrate. These poems draw inspiration from the flora, fauna and habitats native to Singapore and explore our relationship with the environment at large.41

The poems in this anthology draw inspiration from the flora, fauna and habitats native to Singapore, and explore our relationship with the environment. Ow Yeong, W.K., & Muzakkir Samat. (2015). From Walden to Woodlands: An Anthology of Nature Poems. Singapore: Ethos Books. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RSING S821 FRO).

The poems in this anthology draw inspiration from the flora, fauna and habitats native to Singapore, and explore our relationship with the environment. Ow Yeong, W.K., & Muzakkir Samat. (2015). From Walden to Woodlands: An Anthology of Nature Poems. Singapore: Ethos Books. Collection of the National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RSING S821 FRO).

In Eric Tinsay Valles’ “Singapore River on Exhibit”, a poem published in 2015 and inspired by an exhibition at the Asian Civilisations Museum, the poet pays tribute to what must have been abundant aquatic life teeming beneath the murky waters of the Singapore River (before it was cleaned up), alongside the multicultural, multilingual tapestry of commerce taking place along its shores:

Majestic in the middle of a frame,

A green streak undulating like grass snake,

pristine on uncluttered canvas,

you draw orang laut dreaming of tomorrow

on a boat pulling away in the muddy water

until they are washed away from the scene.

They bend down, count the day’s catch,

watch you run past them.”42

Here, the Singapore River is observed from a safe (and clean!) distance within a frame at an exhibition. However, this is not another poem decrying the ravages of progress, but a lyrical musing that ponders on the river’s versatility and enduring mystique:

Cycles of drought and rain, urban renewal

neither detain your dance nor silence your hum.

You are slighted by tourists distracted by the Merlion

spitting in envy at the floating Sands garden.

Shoot a spray at the passing glory

as you rush home to the strait.

Twigs of time scrape against imagery

as you pass by and through me.43

The Singapore River, in the eyes of this poet, hums with life despite its present urban-renewed look and smoothly glides past the gleaming glass-and-steel of Marina Bay Sands. Its dignity inspires the poet to “write blank verses” having witnessed the changing tides of history. Valles’ poem, while unapologetically highlighting the tourist attractions that have sprung up near the river, pays tribute to an enduring natural landmark.

The skyline showing the early signs of dramatic changes along the Singapore River in the 1960s. The tallest building is the Bank of China, designed in the Art Deco style. George W. Porter Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

The skyline showing the early signs of dramatic changes along the Singapore River in the 1960s. The tallest building is the Bank of China, designed in the Art Deco style. George W. Porter Collection, courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

Nature in the Home

Homegrown poetry increasingly reflects a sense of peaceful negotiation even as poets engage in an ongoing dialogue with the constant changes brought about by urban renewal initiatives across the island.

Aaron Maniam’s 2019 poem, “My Mother’s Garden”,44 is one such poem that finds comfort in domesticity in its juxtaposition of familial love with the imagery of nature set within the safe embrace of the poet’s own garden:

Only today, I realise how this place

And your gentle, parenting patience

Taught me my first metaphors:

Bird’s nest, elephant ears , fingers

Greener than leaf or pasture resisting

Incursions from shaving brushes

And grass alive with animal spirits –

[…]

Years of grafted stems, crafted stories,

Dug to root and reality in this new place:

All your loves, labours, litanies

Defying name and number as they

grow, grow.45

In these lines, flora, fauna and faith in the nurturing qualities of domestic bliss come together to provide continuity and growth for the elderly and younger members of the family. Situated within the safety of the family home, the poet pays homage to a motherly figure who has nurtured not merely plants and birds but also the members of her household. The poem renews faith that charity – reflected through the nurturing of nature – starts within the family unit, and flourishes along a growth trajectory to the wider world beyond.

Bringing the winding odyssey of past lyrical-sojourners at the beginning of this exploratory journey to a close, Maniam’s poem is reflective of a later generation of poets who negotiate the curves ahead with a growing, confident voice, armed with an established identity right at home.

Michelle Heng is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She curated the tribute showcase, “Edwin Thumboo – Time-travelling: A Poetry Exhibition”, in 2012, and compiled and edited an annotated bibliography on Edwin Thumboo titled Singapore Word Maps: A Chapbook of Edwin Thumboo’s New and Selected Place Poems (2012) as well as the Selected Poems of Goh Poh Seng (2013).

Michelle Heng is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She curated the tribute showcase, “Edwin Thumboo – Time-travelling: A Poetry Exhibition”, in 2012, and compiled and edited an annotated bibliography on Edwin Thumboo titled Singapore Word Maps: A Chapbook of Edwin Thumboo’s New and Selected Place Poems (2012) as well as the Selected Poems of Goh Poh Seng (2013).

NOTES

-

Ng, L. (2019). Introduction (p. 1). In Azhar Ibrahim, et al. (Eds.), Contour: A lyric cartography of Singapore. Singapore: Published by Pagesetters Services Pte Ltd for Poetry Festival Singapore. (Call no.: RSING S821 CON) ↩

-

Thumboo, E., & Valles, E.T. (Eds.). (2019). The nature of poetry (p. xiv). Singapore: National Parks Board. (Available via PublicationSG) ↩

-

Thumboo & Valles, 2019, p. xiv; Leyden, J. (2012). Sejarah Melayu (pp. 33–36, 40–46). Kuala Lumpur: Silverfish Books Sdn Bhd. (Call no.: RSING 959.1 SEJ) ↩

-

Liaw, Y.F. (2013). A history of classical Malay literature (p. 356). Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. (Call no.: RSEA 899.2809 LIA) ↩

-

Thumboo & Valles, 2019, p. xiv; Holden, P. (2009). Introduction: Literature in English in Singapore before 1965 (pp. 8, 43). In A. Poon, P. Holden & S.G.-L. Lim (Eds.), Writing Singapore: An historical anthology of Singapore literature. Singapore: NUS Press; National Arts Council Singapore. (Call no.: RSING S820.8 WRI) ↩

-

Gak-Stok-Sin. (1907, December). Nature’s secret. The Straits Chinese Magazine, 11 (4) 131–175, p. 150. Singapore: Koh Yew Hean Press. (Call no.: RRARE 959.5 STR; Accession no.: B03057023I) ↩

-

Holden, 2009, p. 8. [Note: Holden writes that while the editors of The Straits Chinese Magazine “sailed close to the wind of colonial power,… [they] engaged in [the] imagining of communities that exceeded the racial classifications of colonial plural society” as they attempted the “bringing together of a community of ‘Straits-born people’.”] ↩

-

Lee, T.P. (1985). Introduction (p. 453). In E. Thumboo, et al. (Eds.), The poetry of Singapore. Singapore: Asean Committee on Culture and Information. (Call no.: RSING S821 POE). [Note: By writing in English, Lee notes that a poet in Singapore manifests rather naturally some literary assumptions of the English poetic tradition.] ↩

-

Eliot, T.S. (2019). The waste land. London: Faber & Faber. (Call no.: 821.912 ELI) ↩

-

Ogihara-Schuck, E. (2015). Introduction (pp. 8–10). In E. Ogihara-Schuck & A. Teo. (Eds.), Finding Francis: A poetic adventure. Singapore: Ethos Books. (Call no.: RSING S821 NG) ↩

-

Ogihara-Schuck & Teo, 2015, pp. 40–41. ↩

-

Ogihara-Schuck & Teo, 2015, p. 48. ↩

-

Ogihara-Schuck & Teo, 2015, p. 50. ↩

-

Gui, W. (2017). Global Modernism in colonial Malayan and Singaporean literature: The poetry and prose of Teo Poh Leng and Sinnathamby Rajaratnam. Postcolonial Text, 12 (2), 1–18, pp. 1–8. Retrieved from Postcolonial Text website. ↩

-

Gui, 2017, p. 8. ↩

-

Teo, K.L. (1955). I found a bone (p. 74). In E. Ogihara-Schuck & S. Kum (Eds.) (2016), I found a bone and other poems. Singapore: Ethos Books. (Call no.: RSING S821 NG) ↩

-

Ogihara-Schuck & Teo, 2015, pp. 4–5. [Note: The Sook Ching massacre, carried out from 21 February to 4 March 1942, refers to the Japanese military operation aimed at eliminating anti-Japanese elements from the Chinese community in Singapore. Chinese males between the ages of 18 and 50 were summoned to various mass screening centres and those suspected of being anti-Japanese were summarily executed. For more information, see Ho, S. (2013, June 17). Operation Sook Ching. Retrieved from Singapore Infopedia website.] ↩

-

Chng, H. (2016, November 20). S’pore’s first zoo was not in Mandai. One of the earliest was started by an “Animal Man” who went around with a pet tiger. Retrieved from Mothership website. ↩

-

Lim, T.S. (1953). Lallang (p. 126). In A. Poon, P. Holden & S.G.-L. Lim (Eds.). (2009), Writing Singapore: An historical anthology of Singapore literature. Singapore: NUS Press; National Arts Council Singapore. (Call no.: RSING S820.8 WRI) ↩

-

Gwee, L.S., & Heng, M. (Eds.). (2012). Edwin Thumboo: Time-travelling: A select annotated bibliography (p. 32). Singapore: National Library Board. (Call no.: RSING S821 EDW) ↩

-

Ee, T.H. (1997). The cough of Albuquerque (p. 28). In L.G. Leong (Ed.), Responsibility and commitment: The poetry of Edwin Thumboo. Singapore: Published for Centre for Advanced Studies by Singapore University Press. (Call no.: RSING S821.09 EE) ↩

-

Thumboo, E. (2011). The cough of Albuquerque [Book extract]. Retrieved from National Online Repository of the Arts (NORA) website. ↩

-

Eliot, T.S. (1951). Collected poems, 1909–1935 (p. 37). London: Faber & Faber Limited. (Call no.: RDET 821.912 ELI) ↩

-

In Virgil’s Aeneid, an epic poem in Latin, Dido flees from her ruthless brother Pygmalion, who had her husband killed. She subsequently builds a pyre after losing her lover Aeneas, falls on her sword and dies on the pyre. ↩

-

Lim, I. (2019). Planting feet: On the postcolonial pastoral in Edwin Thumboo’s “The Cough of Albuquerque”. Paper presented at the Singapore Literature Conference 2019. ↩

-

Lim, 2019. ↩

-

Lim, 2019. ↩

-

Goh, P.S. (1976). Eyewitness. Singapore: Heinemann Educational Books. (Call no.: RSING 828.995957 GOH) ↩

-

Yap. A. (2013). The collected poems of Arthur Yap with an introduction by Irving Goh. Singapore: NUS Press. (Call no.: RSING S821 YAP) ↩

-

Tay, E. (2014). On places and spaces: The possibilities of teaching Arthur Yap (pp. 106–107). In W. Gui (Ed.), Common lines and city spaces: A critical anthology on Arthur Yap. Singapore: ISEAS Publishing. (Ebook available on NLB OverDrive) ↩

-

Ow Yeong, W.K., & Muzakkir Samat. (Eds.). (2015). From Walden to Woodlands: An anthology of nature poems. Singapore: Ethos Books. (Call no.: RSING S821 FRO) ↩

-

Valles, E.T. (2010). Singapore River on Exhibit (pp. 91–92). In W.K. Ow Yeong & Muzakkir Samat (Eds.). (2015), From Walden to Woodlands: An anthology of nature poems. Singapore: Ethos Books. (Call no.: RSING S821 FRO) ↩

-

Ow Yeong & Muzakkir Samat, 2015, pp. 91–92. ↩

-

Maniam, A. (2019). My mother’s garden (pp. 36–37). In E. Thumboo & E.T. Valles (Eds.), The nature of poetry. Singapore: National Parks Board. (Available via PublicationSG) ↩