How Jurong Bird Park was Hatched

On the 50th anniversary of its opening, Zoe Yeo gives us a bird’s-eye view of the setting up of one of Singapore’s most popular tourist attractions.

Jurong Bird Park is one of Singapore’s more successful attractions, beloved by tourists and locals alike. I recall numerous trips during my formative years with my parents and siblings to observe the birds. I even took enough pictures to obtain the “I am a Young Ornithologist” badge, which was awarded by the Singapore Science Centre under its Young Scientist Badge Scheme. Now as an adult, I still love visiting the park to marvel at the different bird species.

I am not the only one who enjoys going there. In 2019, before the Covid-19 pandemic hit, the park welcomed 750,000 visitors who came to see the 3,500 birds that make up 400 species. However, what many may not know are the myriad challenges that the park had to overcome just to get to the point of opening on that fateful day some 50 years ago in January 1971.

The plan for a bird park was the brainchild of Minister for Finance Goh Keng Swee in the late 1960s. He said the idea first occurred to him in September 1967 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, during a World Bank meeting when “during a free moment, [he] visited the Rio Aviary”.1

The following year, Goh visited the aviary in Bangkok, which convinced him that it would be a good idea to set up a bird park in Singapore. As he noted: “The authorities managing the Bangkok Aviary which I made a point to visit assured me their main problem was what to do with the millions of bahts they had accumulated over the years.”2

Goh proposed to establish the bird park in Jurong because while touring the area scouting for possible sites, he “found that there were some islands, some area along the Jurong River which was not used, covered with bush or undergrowth. So I said it’s a good idea to make it beautiful.”3

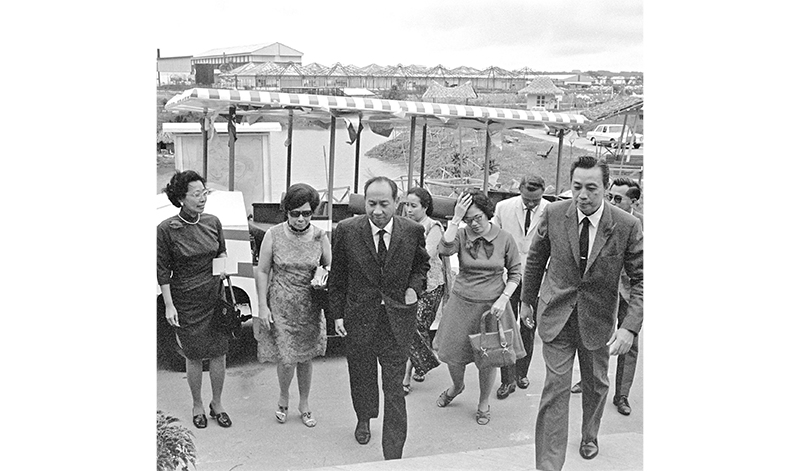

At the inaugural meeting of the Jurong Town Corporation in June 1968, Goh shared his vision of a bird park for Singapore and by the end of the year, the site for the new attraction had been identified: a 20.2-hectare plot on the western slope of Bukit Peropok (now known as Jurong Hill). The eminent aviculturist and bird curator John Yealland and aviary architect J. Toovey, both from the Zoological Society of London, were involved in planning the new aviary. (Yealland was regarded as the “world’s top bird curator” at the time.4)

The society provided the services of the two experts for free and during their two-month visit here, they drew up the plans and design for the aviary. The two men also promised that the aviary “would easily be Asia’s best, and one of the best in the world because of its size and unique terrain”.5

When the idea of a bird park was mooted in 1968, Singapore had gained independence just three years before. As a result, there were questions about whether an aviary was the best way to use limited resources. As Goh himself acknowledged at the park’s opening in January 1971: “It is more than possible that there may be people in Singapore who question the propriety of building the Jurong Bird Park at a time when the Republic is assailed by so many problems.”6

Goh described the origins of the bird park as “impeccable, and its conception, immaculate”. He also noted that the park would be self-supporting and that it would be open to all, for a modest fee. On the other hand, Goh said he did not want to overstate the case for the park: “It is well to concede from the outset that the Bird Park will not make our society more rugged…”. In addition, he added that the bird park would “have negligible effect on the productivity of workers in the Republic”. The park’s efficacy as a means of tightening national cohesion was also “open to doubt, as is its contribution to raising cultural and education standards of the population. I am afraid the Bird Park will achieve none of these admirable ends,” he said, somewhat tongue-in-cheek. “But it will add to the enjoyment of our citizens, especially our children. At the risk of appearing less than God-fearing, I give this as my final justification.”7

A Rocky Start

One of the early challenges faced by the bird park was that it had to have a significant bird collection in order to attract visitors. And since the endeavour started from scratch, the park’s pioneer chairman and managing director, Woon Wah Siang, pursued many different channels in order to find enough birds to fill the park. He was reported to have said: “I attended every National Day cocktail party just to ask for birds.”8

Beyond attending cocktail parties, Woon also approached ambassadors and foreign dignitaries here for help. He penned a 10-page letter to the British High Commissioner, Arthur de la Mare, listing over 350 bird species and seeking assistance in obtaining these birds from the United Kingdom. The document was first forwarded to the London Zoo, who felt that they had “already been of considerable assistance” after providing guidance and donating a number of birds and they “did not feel like that they could reasonably be expected to do more”. The London Zoo also claimed to be in dire financial straits and could not “envisage any further gifts being made”.9 The United Kingdom’s Wildfowl Trust were also approached but they shared the same sentiments as the London Zoo.10

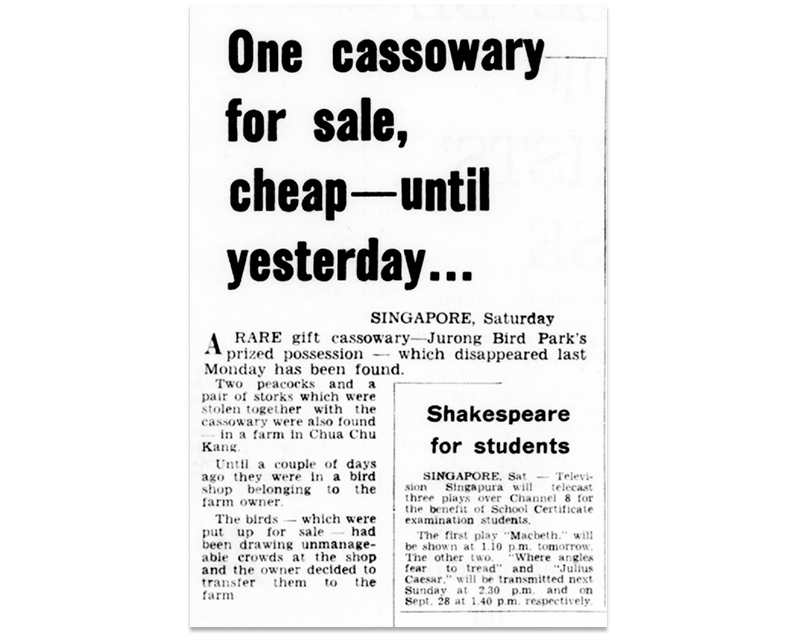

In addition to obtaining birds, there was also the challenge of keeping them safe. On top of preventing the birds from flying away, the bird park had to deal with thefts as well. In September 1969, a rare cassowary, two peacocks and a pair of storks were actually stolen from the park and sold off. 11

Apparently, a day after the birds were stolen, three men approached a bird shop in Geylang with an offer to sell “Indonesian birds”. The shop assistant asked to see the birds and was taken to a house in Changi. “A price of $500 was offered, but this was later bargained down to $250. The shop assistant then took them back to his shop and paid the money there.”12

The birds were then put up for sale at the shop but they began “drawing unmanageable crowds and the owner decided to transfer them to [his] farm” in Choa Chu Kang. After reading about the stolen birds in the newspapers, the owner contacted the police who recovered the birds.13

There were also engineering challenges involved in building the bird park. The flight-in aviary used 18 steel cables, each weighing about three tons, which had to be stretched across the top of the 2-hectare space. On either end of the slope, where the cables were attached, piling was necessary to ensure that these cables did not come loose.14

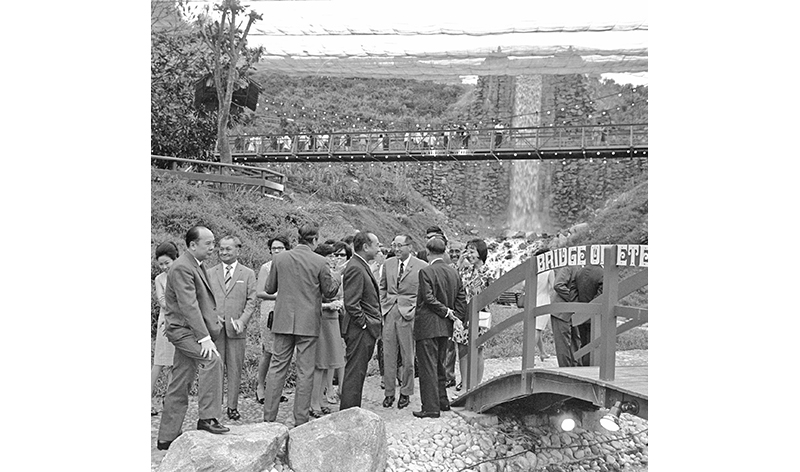

But it was perhaps the man-made waterfall that was the most challenging to build. Said to be the highest in the world at the time, it had “8,000 gallons of water pouring from a height of 100 feet every minute”. Huge granite rocks were used as the backdrop, “each weighing no less than a ton”. These boulders had to be held together with steel cables to prevent them from sliding down.15

Eventually, all the challenges were overcome and a date was set for the opening: 29 June 1970. However, on 28 June, The Straits Times announced that the park’s opening, scheduled for the following day, would be postponed. The two-paragraph statement reported that the “aviaries, the man-made waterfall and the flight-in aviary were all completed but certain improvements had yet to be made”.16

According to Lee Oon Pong, the director of Employment at the Ministry of Defence (1970–75), who worked closely with Goh, the last-minute postponement was because the latter did not feel that one of the key attractions, the man-made waterfall, was up to mark.17

Goh, who was by then Minister for Defence, along with board members of Jurong Town Corporation, had visited the bird park about a week before the scheduled official opening. When he got to the waterfall, however, Goh was appalled when he saw muddy water cascading down what was supposed to be a highlight of the park. The water was brown because the waterfall was pumping water from the duck pond, which had been contaminated with mud due to the ongoing construction works at the park.18

Recalled Lee: “[He] looked at Woon Wah Siang and said ‘Wah Siang, you want me to open this?’ [Woon] was dumbfounded. [Goh said], ‘If you want me to open the bird park… when I throw a five-cent coin into the brook… I expect to see [it] at the bottom, then I’ll open it.’ … Then he just walked off.” Woon had to scramble to call up all the invited guests to apologise.19

The bird park swiftly acquired a filtration plant costing a quarter of a million dollars. It was installed near the waterfall and was “capable of filtering and cleaning the water so that what thunders down is crystal clear”.20

In August 1970, The Straits Times reported that as there was still ongoing work in the bird park, there would be a four-month wait until December that year before the attraction could open to the public, even though the aviaries, lakes and the artificial waterfall had been built. But not everyone realised that the park’s opening had been postponed and unsuspecting visitors were turned away.21

A month later, in September, the bird park again announced that its opening would be delayed as it would be introducing two new innovations – control of temperature of the aviary through landscaping and a new feeding method – both aimed at improving the welfare of the feathered residents of the park.22

With a new filtration system in place and all amenities ready, the park was finally opened on 3 January 1971. It was reported to be the biggest aviary in the world at the time, sprawling over 20.6 hectares with more than 7,000 birds, some of them gifted to the park by 12 countries, 40 private collectors and seven zoos.23 At the opening, Goh, still looking to make more improvements, issued a call to guests for more birds, specifically falcons.24

“I had originally planned to introduce falconry displays as part of the bird park’s activities,” he said. Goh added, in his inimitable tongue-in-cheek manner, that he was not hopeful that “modern industrial nations” would have anyone but “perhaps in some quiet corner of the world, in some last refuge of reaction and obscurantism, people still happily engage in falconry without let or hinderance from tiresome moralisers. If one of your Excellencies represents such a 20th century Ruritania, may I suggest that our respective Governments immediately enter into a Bilateral Technical Assistance Agreement for the Promotion of Falconry in Singapore”.25

The absence of falconers was apparently not a major deterrence and the park quickly became a popular new haunt for Singaporeans, recording more than 8,000 visitors on the first Sunday of its opening.26 A year later, the park was reported to have collected more than $1 million in revenue since its opening, with some 645,800 people having visited by then. The park also chalked up a low bird mortality rate of 0.6 percent, one of the lowest in the world where the mortality rate averaged around 2.5 to 3 percent.27

Breeding and Conservation

Apart from being a place for the general public to admire and appreciate birds, the park also planned to raise money by breeding and selling them. The first breeding programme started in 1972, with the aim of breeding “the 350 species in the park for sale to individuals and zoos at home and aboard”.28

The first few species successfully bred for sale were the night heron, ibis, white-crested laughing thrush and the water-fowl. The prices of these birds depended on the demand and rarity of the species.29 In 1976, the breeding of foreign birds in the park was reported to be a “tremendous success”, with a total of 137 birds, mostly species from Europe, America, India and Egypt, hatching the year before. These birds included the spoonbill, the ring-necked parakeet, the Alexandrine parakeet, the black swan and the scarlet ibis.30

The bird park eventually stopped breeding birds for sale and instead embarked on efforts to conserve rare bird species, especially those from Southeast Asia. In 1995, the park became the first zoological institution to breed the black hornbill, a vulnerable species native to Southeast Asia.31

The straw-headed bulbul, a critically endangered species native to Singapore, was also successfully bred by Jurong Bird Park in 2017. The bulbul is coveted by songbird traders due to its unique vocalisation, making it a target of poachers.32

The park also works with the National Parks Board, Nanyang Technological University and researchers on the Singapore Hornbill Project. The oriental pied hornbill disappeared in Singapore in the mid-1800s because of hunting and loss of habitat, but re-emerged some 140 years later when a pair of wild hornbills was recorded on Pulau Ubin in 1994.33

The collaborative project initiated in 2004 aims to enhance the population and distribution of this locally endangered bird. This includes providing artificial nesting boxes and reducing anthropogenic threats – such as overzealous bird watchers and photographers disturbing nesting activities – by fencing nesting areas with thick vegetation to minimise disturbance. About a decade ago, 40 to 50 hornbills were recorded on Pulau Ubin and at least two pairs had flown to Changi.34 Since then, oriental pied hornbills have been spotted in various locations around Singapore.

The bird park also participates in international projects on the conservation of endangered species. In 2018, some 60 Santa Cruz ground doves were flown from the Solomon Islands to Singapore, becoming the world’s only “assurance colony” of the species outside of the Islands. A large population of the ground doves had been wiped out in a volcanic eruption in Tinakula in 2018, and the 60 birds were part of a flock that had been confiscated from poachers after the eruption. The assurance colony ensures that a population of the species is safe under human care in case of a catastrophic population decline in the wild. In 2019, the Jurong Bird Park became the first zoological institution to breed these birds.35

Celebrating 50 Years

Since its opening 50 years ago, the Jurong Bird Park has welcomed 30 million visitors. To commemorate the half century since the opening of the aviary, the park planned a year-long celebration with events and activities throughout 2021. The aviary kickstarted its jubilee celebrations by reverting to its 1971 admission price of $2.50 for all residents in the month of January 2021. (The usual price of a ticket for local residents is currently $34 for adults and $23 for children.)

Big John, a cockatoo who has been with the aviary since its opening in 1971 will also be making appearances in special shows throughout the year. The bird park also invites people to upload photographs taken in the park to Facebook and Instagram with the hashtag #JBP50. These photos would be featured as part of the aviary’s “Memories of Jurong Bird Park” exhibition in 2021.36

In 2016, it was announced that Jurong Bird Park would be moving to Mandai to form an integrated nature and wildlife precinct together with a new Rainforest Park and the three existing wildlife parks in Singapore (the Singapore Zoological Gardens, the Night Safari and the River Safari).

The new and improved bird park will include themed walk-through aviaries designed after different regions and ecosystems of the world – stretching from the rainforests of Africa to the bushlands of Australia – allowing visitors to immerse themselves in the naturalistic habitats of the birds.37 Slated to open in 2022, it will mean moving out from Jurong after 51 years, which will no doubt sadden some. However, the new location will allow the bird park to enjoy the synergies of being close to similar attractions. In addition, the new designs for the various aviaries will allow the bird park’s ambitions to truly take flight.

Zoe Yeo is an Associate Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She is part of the team that oversees the statutory functions at the National Library Board. She manages the Legal Deposit function and collection, including its collection policies, workflows and enforcement as well as engagement with publishers and the public.

Zoe Yeo is an Associate Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She is part of the team that oversees the statutory functions at the National Library Board. She manages the Legal Deposit function and collection, including its collection policies, workflows and enforcement as well as engagement with publishers and the public.

NOTES

-

Ministry of Culture. (1971, January 3). Speech by Dr. Goh Keng Swee, Minister of Defence, at the opening of Jurong Bird Park on Sunday, 3rd January 1971 at 6.00 pm [Speech]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website; Goh tells why the bird park was built. (1971, January 4). The Straits Times, p. 15. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ministry of Culture, 3 Jan 1971. ↩

-

Tan, S.S. (2015). Goh Keng Swee: A portrait (p. 175). Singapore: Editions Didier Millet. (Call no.: RSING 959.5704092 TAN-[HIS]) ↩

-

Tsang, S., & Hendricks, E. (2007). Discover Singapore: The city’s history & culture redefined (pp. 96–97). Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. (Call no.: RSING 959.57 TSA-[HIS]) ↩

-

Yeo, T.J. (1969, January 3). Work on $1 mil. Aviary at Jurong. The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ministry of Culture, 3 Jan 1971. ↩

-

Ministry of Culture, 3 Jan 1971. ↩

-

New attractions almost every year to whip up visitor interest. (1995, February 24). The Straits Times, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The National Archives, United Kingdom. (1970). FCO 24/901: Request for assistance in obtaining rare birds for Jurong Bird Park, Singapore. Accessed at National Archives of Singapore. (Accession no.: FCO 24/901) ↩

-

One cassowary for sale, cheap – until yesterday. (1969, September 14). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 14 Sep 1969, p. 8. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 14 Sep 1969, p. 8. ↩

-

Fong, L. (1971, January 3). Rainbow on the falls on a sunny afternoon. The Straits Times, p. 20. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 3 Jan 1971, p. 20. ↩

-

Park opening postponed. (1970, June 28). The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lim, J. (Interviewer). (2002, August 15). Oral history interview with Lee Oon Pong [MP3 recording no. 002510/52/51]. Accessed at the National Archives of Singapore. [Note: Written permission to the National Archives is required for use.] ↩

-

Oral history interview with Lee Oon Pong, 15 Aug 2002. ↩

-

Oral history interview with Lee Oon Pong, 15 Aug 2002. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 3 Jan 1971, p. 20 ↩

-

Another 4 months wait for bird lovers. (1970, August 26). The Straits Times, p. 8. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Delay – strictly for some rare birds. (1970, September 12). Singapore Herald, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

What a lark! This bird park which has almost everything… (1970, December 17). Singapore Herald, p. 13. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ministry of Culture, 3 Jan 1971. ↩

-

Ministry of Culture, 3 Jan 1971. ↩

-

Har, N. (1971, January 11). Thousands spend rest day at bird park. The Straits Times, p. 10. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Jurong birds netted $1m last year. (1972, January 19). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Chia, P. (1972, August 3). Jurong Bird Park to breed 350 species for sale. The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ng, E. (1972, September 12). Exotic bird business gets off the ground. The Straits Times, p. 26. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; The Straits Times, 3 Aug 1972, p. 6. ↩

-

Bird park’s breeding success. (1976, August 24). The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Wildlife Reserves Singapore Group. (2021). Hornbills and toucans. Retrieved from Wildlife Reserves Singapore website. ↩

-

Wildlife Reserves Singapore Group. (2019, January 23). Two highly threatened bird species successfully bred at Jurong Bird Park. Retrieved from Wildlife Reserves Singapore website. ↩

-

Teo, R. (2012, February). Conserving hornbiills in the urban environment. Citygreen, (4), 130–135, p. 132. Retrieved from National Parks Board website ↩

-

Teo, Feb 2012, p. 134. ↩

-

Wildlife Reserves Singapore Group. (2018, August 17). Jurong Bird Park home to possibly half the world’s Santa Cruz ground-dove population. Retrieved from Wildlife Reserves Singapore website. ↩

-

Email correspondence with Wildlife Reserves Singapore, 4 May 2021. ↩

-

Email correspondence with Mandai Park Holdings, 7 May 2021. ↩