Mulan’s Many Faces: The Different Versions in the Asian Children’s Literature Collection

Goh Yu Mei examines the National Library’s Asian Children’s Literature Collection to see how the story of Mulan has evolved over time, while Michelle Heng reviews other Asian tales in the acclaimed collection.

“唧唧复唧唧,木兰当户织。不闻机杼声,惟闻女叹息。” 1

(Translation: Click, click, click, click, Mulan is at her loom. One could not hear the sound of the loom weaving, but only Mulan’s sigh.”)

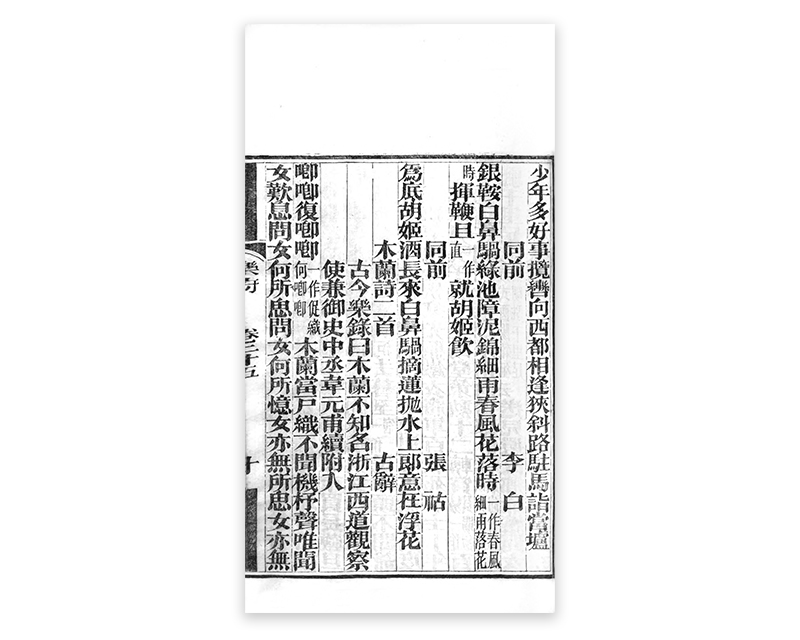

These are the opening lines in《木兰辞》(Mulan Ci; The Ballad of Mulan),2 believed to have been composed during the Northern dynasties period (北朝, c. 386–581).3

Widely accepted as the earliest written version of the story of Mulan (木兰), the 62-line poem tells the inspiring story of a young woman who disguises herself as a man so that she can take her aged father’s place when he is conscripted into the army to fight the Tartars. The ballad was subsequently included in《乐府诗集》(Yuefu Shiji; Collection of Yuefu Poetry), an anthology of poetry compiled by Guo Maoqian (郭茂倩) during the Song Dynasty (960–1276).

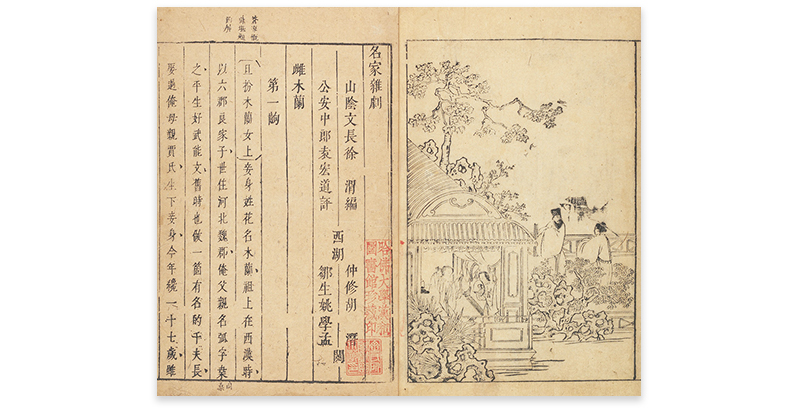

During the Tang dynasty (618–907), the story was retold as《木兰歌》(Mulan Ge; The Song of Mulan), a poem written by Wei Yuanfu (韦元甫). Several centuries later, during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), Xu Wei (徐渭) composed the opera《雌木兰替父从军》(Cimulan Tifucongjun; Female Mulan Took Her Father’s Place in the Army). The story was then turned into the novel《北魏奇史闺孝烈传》(Beiwei Qishi Guixiao Liezhuan; The Legendary Story of a Filial and Heroic Girl from the Northern Wei) by Zhang Shaoxian (张绍贤) during the Qing dynasty (1644–1912).4

Although filial piety and loyalty are constant themes in the different representations of Mulan, these values are portrayed differently by different authors. In Zhang Shaoxian’s novel, for instance, Mulan takes her own life when she is forced to choose between returning home to care for her parents (i.e. filial piety), and remaining in the army to serve the emperor (i.e. loyalty). The tragic ending in this narrative of Mulan hints at a criticism of the interpretations of filial piety and loyalty in earlier versions of the tale.5

Recent efforts to reimagine the story of Mulan consist of books, stage adaptations, television serials and movies. These include the chapter “White Tigers” in Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Woman Warrior: Memoirs of a Girlhood Among Ghosts (1976)6 and, of course, Disney’s Mulan, comprising an animated film in 1998 and a live-action drama film in 2020.

Given that the tale is about 1,500 years old, the story of Mulan has inspired numerous books and iterations in various languages and for different age groups, including children. Some of these titles are available in the Asian Children’s Literature Collection (ACL Collection) of the National Library.

The authors or editors of these titles have adopted different approaches in their versions by combining elements of older Mulan stories with new reinterpretations. These can be broadly categorised into two groups: retelling of The Ballad of Mulan, largely sticking to the original poem, and the rewriting of the story of Mulan, which involves adding significant new elements.

Retelling The Ballad of Mulan

“脱我战时袍,著我旧时裳。当窗理云鬓,对镜贴花黄。”7

(Translation: I remove my armour, change into my old dress; comb my hair by the window, and apply yellow powder in front of the mirror.)

Several titles in the ACL Collection closely follow the format in The Ballad of Mulan. The Song of Mu Lan (1995) by Jeanne M. Lee is a direct translation of the ancient poem alongside its original Chinese text.8 The English translation and the poem, which is faithfully reproduced in traditional Chinese calligraphy by Lee’s father, Chan Bo Wen, are juxtaposed against watercolour paintings on silk by Lee, each corresponding to a scene described in the respective verses.

Lee dedicates the book “to all women, young and old” and notes that “the verses of the poem are still taught to children in China today and are sung in Chinese opera in different dialects”. These hint at the values of filial piety and loyalty conveyed in the story of Mulan, which are still relevant today and that Mulan is a good role model for women.

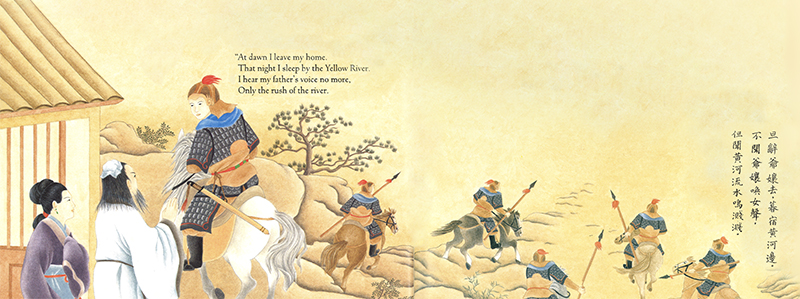

Another book, Song Nan Zhang’s The Ballad of Mulan (1998), has adopted the same way of depicting the story as Lee, with the narrative in English and the original Chinese poem set against drawings depicting the different scenes.9 (Zhang, who was born in Shanghai and later migrated to Canada, also drew the illustrations in the book.)

In Zhang’s interpretation, each drawing is enclosed within a frame which is similar to how early Chinese books are bound. Although Zhang follows the original storyline closely, he also includes new details and lines. For example, the following lines describe the scene where Mulan appears before her fellow soldiers in female attire:

“What a surprise it was when Mulan appeared at the door! Her comrades were astonished and amazed. ‘How is this possible?’ they asked.”10

The original line from The Ballad of Mulan, “出门看伙伴,伙伴皆惊恐”, only states that when Mulan exits from her room and appears in front of her fellow soldiers, they are astonished. Her fellow soldiers’ question is a minor detail that Zhang has added.

At the end of Zhang’s book, there is a very short section titled “Historical Notes on Mulan” which explains the historical context of Mulan’s life and the development of the story from the early days until the present. It notes that the story (and poem) is a well-known folk tale studied by schoolchildren in China today. Zhang writes that the story continues to inspire Chinese women, and he dedicates the book to “everyone with an interest in ancient Chinese culture and literature”.

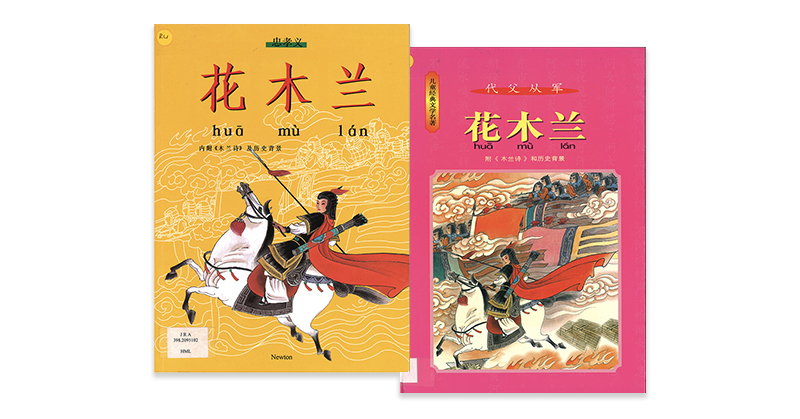

In Singapore, the story of Mulan has been rewritten as a Chinese picture book,《花木兰》(Hua Mulan), published by Newton Publications. Written by Li Xiang (李想) with illustrations by Zhang He (张禾), it follows the original storyline closely, although the author has added minor new scenes such as Mulan’s father teaching her martial arts.

The picture book was first published in 1998, with a new edition two years later.11 The 1998 edition contains the original poem in classical Chinese, a retelling of the story with additional details and a section on the historical context of the ballad. The 2000 edition includes the original poem rendered in simplified Chinese, which the 1998 version does not have.

Re-creating the Story of Mulan

“雄兔脚扑朔,雌兔眼迷离;两兔傍地走,安能辨我是雄雌?”12

(Translation: The male rabbit hops rapidly, while the female rabbit has blurry eyes. When both are running side by side, how can one tell if I am male or female?)

Several other titles about Mulan in the ACL Collection involve much more rewriting, including significant details or scenes not found in the original poem, The Ballad of Mulan.

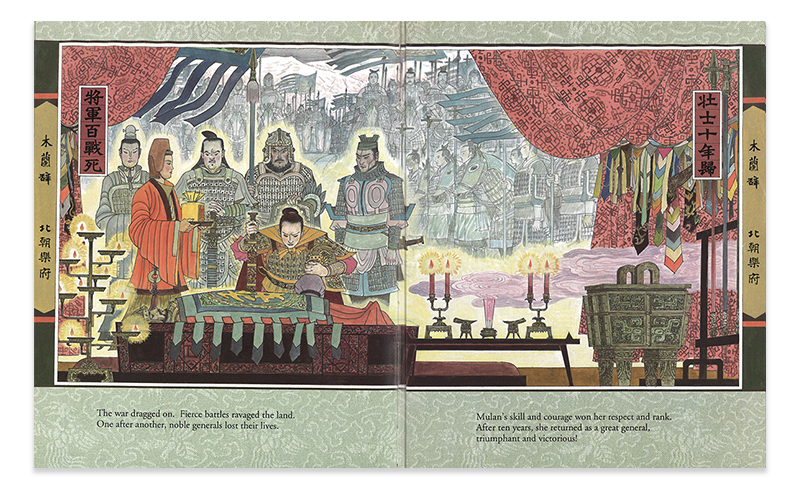

Fa Mulan: The Story of a Woman Warrior (1998) by Robert D. San Souci, and illustrated by Jean Tseng and Mou-Sien Tseng, is one such example. (This version by San Souci was probably the inspiration for Disney’s 1998 animated film).13 In his “Author’s Note”, San Souci explains that he added scenes not explicitly mentioned in the original poem by “drawing on [his] study of the original poem in its historical and cultural context”.14

San Souci notes that the ballad had few details of the campaign against the Tartars so he obtained information on military organisation and strategy, as well as the advice Mulan shares with her generals, from Sun Tzu’s The Art of War. “It seems logical that Mulan, in her rise to generalship, would have studied this essential text in length – even committing its principles to memory,” he adds.15

San Souci also injects an element of romance in his Mulan story, drawing his inspiration from the reference to a pair of male and female rabbits in the original verse that he had interpreted as suggesting a marriage bond.

Other contemporary authors have used details that might have originated from Xu Wei’s opera,《雌木兰替父从军》. For example,《花木兰》(Hua Mulan; 2002) by Yong Chun (永春) mentions Mulan’s surname, Hua (花), along with her father’s name, Hua Hu (花弧), which was first mentioned in Xu’s opera.16 In Mulan: A Story in English and Chinese (2014) by Li Jian, the author writes that “Mulan learned Chinese calligraphy and reading from her father at a young age”,17 while Gang Yi and Xiao Guo’s The Story of Mulan: The Daughter and the Warrior (2007) says that “[Mulan’s] father taught her archery and horseback riding”.18 These embellishments are found in Xu Wei’s opera and not in the original poem.

A Classic Tale

While Mulan’s story strongly reflects Chinese culture and values, different authors deal with these elements in different ways, as the various versions of the story in the ACL Collection demonstrate.

The titles published in North America put more effort into providing background and context. Lee notes that the poem is still being studied in schools and performed as operas in China today. San Souci writes that he has incorporated elements from The Art of War and believes that Mulan could have looked up to the Maiden of Yue (越女; Yue Nü; a legendary swordswoman from the Spring and Autumn period) as a role model. Meanwhile, Zhang dedicates his book to all who are interested in Chinese culture and literature. In many ways, these authors appear to be attempting to explain the cultural context of Mulan’s story to an unfamiliar audience.

On the other hand, the authors whose books are published in Asia appear to take it for granted that their audience has the necessary background. Yong Chun merely notes that Mulan exemplifies the Chinese values of loyalty (忠), filial piety (孝), benevolence (仁) and love (爱), while Li Xiang simply states on the back cover of his book that the original poem《木兰辞》is a gem passed down through history. No extra explanations are given.19

These differences probably arise from the writer’s perception of who the readers will be.

Differences in treatment notwithstanding, the fundamental story of Mulan taking her father’s place in the army has not changed over the last 1,500 years. The enduring popularity of her story is testimony to the fact that this particular tale strikes a deep chord within people, regardless of time period or cultural milieu. And Mulan herself continues to serve as an inspiration and role model for children today.

Of Familial Love and Sacrifice

By Michelle Heng

There is a Chinese proverb, 百善孝为先, which says that filial piety ranks first among all virtues.20 Filial piety is a major tenet of Confucian thought and has remained the cornerstone of Chinese society for thousands of years.21 According to the Classic of Filial Piety (孝经; Xiaojing), a Confucian classic treatise giving advice on filial piety, “Filial piety begins with the serving of our parents, continues with the serving of our ruler, and is completed with the establishment of our own character”.

The values of loyalty, respect and obedience to one’s parents and seniors, reflected in the tale of Mulan, are also universal virtues that find common ground in several Asian tales centred on sacrifices made by children for their elderly kinfolk in the National Library’s Asian Children’s Literature (ACL) Collection.22

An example of this is a retelling of The Voice of the Great Bell (1989),23 the story of a pure and beauteous Chinese maiden, Ko-Ngai, who makes the ultimate sacrifice when the emperor threatens to execute her father, Kouan-Yu, after he fails repeatedly to create the greatest of bells “strengthened with brass, deepened with gold, sweetened with silver” despite gathering the best artisans in the country for the monumental task. When the cast is made and the mould removed, the bell falls apart as the three metals did not combine. Ko-Ngai then sacrifices herself, as the only way the metals will bond is if a pure young maiden is thrown into the molten mass.

Other Asian tales focusing on the themes of familial love and filial devotion include those from Korea, Japan and Nepal. In the Korean tale titled In The Moonlight Mist (1999),24 the heavenly king rewards a woodcutter who sacrifices his own happiness for his mother’s welfare by reuniting him with his family in heaven.

A son’s loving devotion to his elderly mother is fittingly rewarded and celebrated in this Korean folktale retold by Daniel San Souci. San Souci, D. (1999). In the Moonlight Mist: A Korean Tale. Honesdale, PA: Boyds Mills Press. Asian Children’s Literature Collection, National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RAC 398.209519 SAN-[ACL]).

A son’s loving devotion to his elderly mother is fittingly rewarded and celebrated in this Korean folktale retold by Daniel San Souci. San Souci, D. (1999). In the Moonlight Mist: A Korean Tale. Honesdale, PA: Boyds Mills Press. Asian Children’s Literature Collection, National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RAC 398.209519 SAN-[ACL]).

The much-loved Japanese folktale, The Wise Old Woman (1994),25 tells of how a loving farmer shields his aged mother away from a cruel young lord who banishes elderly villagers, when they reach the age of 70, to the mountains and leave them to die there. When a nearby ruler threatens to invade the village unless the lord can perform three impossible tasks, only the farmer’s mother succeeds in solving them. The lord then reverses his decree and declares that elders “will be treated with respect and honour, and will share with us the wisdom of their years”.

Wisdom comes with age and experience, and nowhere is this more apparent than Yoshiko Uchida’s retelling of a traditional Japanese folklore, The Wise Old Woman. Uchida, Y. (1994). The Wise Old Woman. New York: Margaret K. McElderry. Asian Children’s Literature Collection, National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RAC398.20952 UCH-[ACL]).

Wisdom comes with age and experience, and nowhere is this more apparent than Yoshiko Uchida’s retelling of a traditional Japanese folklore, The Wise Old Woman. Uchida, Y. (1994). The Wise Old Woman. New York: Margaret K. McElderry. Asian Children’s Literature Collection, National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RAC398.20952 UCH-[ACL]).

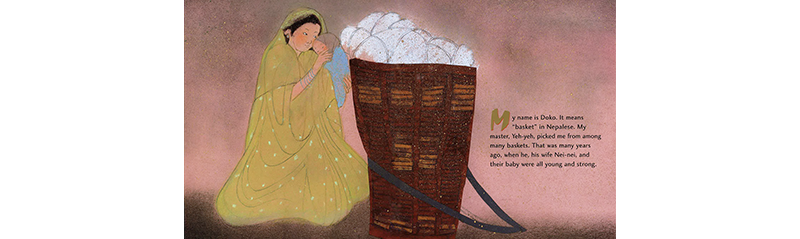

In the Nepalese fable, I, Doko: The Tale of a Basket (2004),26 a man decides to abandon his ailing father by placing him in a basket on the temple steps. The man realises his mistake when his young son asks him to bring the basket back so that the son would not have to buy a new one when the time comes for him to carry his father to the temple to be abandoned. Told from the point of view of the basket called Doko, which has served the family for decades, the moral of the story is to treat old people with respect and deference even when they are ailing and are no longer “useful”.

Told from the perspective of a basket, I, Doko, depicts the significance of filial love in this poignant Nepalese folktale by Ed Young. Young, E. (2004), I, Doko: The Tale of a Basket. New York: Philomel Books. Asian Children’s Literature Collection, National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RAC 813.54 YOU)

Told from the perspective of a basket, I, Doko, depicts the significance of filial love in this poignant Nepalese folktale by Ed Young. Young, E. (2004), I, Doko: The Tale of a Basket. New York: Philomel Books. Asian Children’s Literature Collection, National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RAC 813.54 YOU)

These timeless Asian tales for children have captivated the young and the young at heart alike for many generations. It was for the purpose of raising the profile and increasing the appreciation of Asian-centric children’s literature that the ACL Collection was first initiated by the National Library of Singapore in the 1960s.27

The collection was initially stocked with children’s literature of British and American origins but steadily evolved over the years to reflect a stronger Asian focus. Vilasini Menon, one of the original curators of the collection, recalled being tasked to revamp the ACL Collection: “Singapore was a British colony. There was an existing children’s library, but the collection was in English for the English-speaking people and English expatriates. The books were all about pony-riding and English school stories, which were highly alien to our children.”28

While recognising the collection’s possibilities as a resource for teachers intending to introduce Asian culture and stories to their young charges in Singapore, Menon was also mindful of the possible needs of researchers when making acquisitions. She looked to library review journals to decide which titles should be purchased, and developed the collection’s potential for cross-sectional study by including titles that reflected different attitudes towards Asia and Asians over time.29

In the early 1960s, most of the titles in the collection were translated into English from their original languages because not many English titles were published in Asia.30

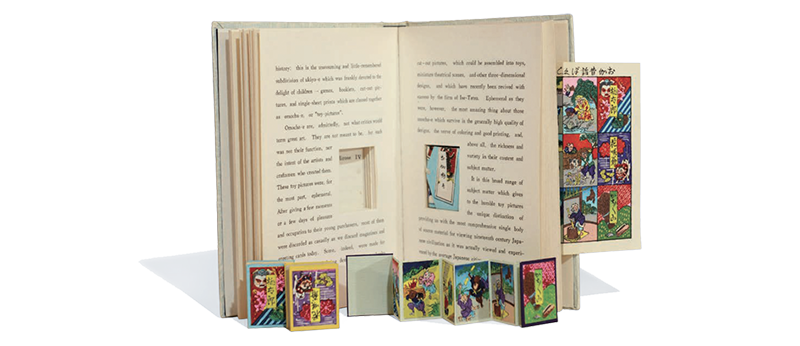

Apart from its Asian-focused intent, the ACL Collection houses a treasure trove of uniquely crafted gems in the bookmaking tradition. Otogi-Banashi: A Miniature Toy-Book from Japan (1969)31 is a bilingual publication penned in Japanese by Tatsugoro Hirose, with the English text by Ann Herring. Embedded within a cut-out space in the pages are three Lilliputian books of much-loved Japanese folktales: “The Old Man Who Makes The Flowers Bloom”, “Momotaro” and “Kachi-Kachi Mountain”. Featuring distinctive woodblock-printed illustrations, the bindings of the miniature books and the slipcover are made of chiyogami, a traditional Japanese paper.32

Otogi-Banashi: A Miniature Toy-Book from Japan contains three miniature books on well-loved Japanese folktales as well as an introductory essay on the history of toy books and woodblock prints. Herring, A., & Hirose, T. (1969). Otogi-Banashi: A miniature toy-book from Japan. Tokyo: Ise-Tatsu. Asian Children’s Literature Collection, National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RCLOS 895.63 HER).

Otogi-Banashi: A Miniature Toy-Book from Japan contains three miniature books on well-loved Japanese folktales as well as an introductory essay on the history of toy books and woodblock prints. Herring, A., & Hirose, T. (1969). Otogi-Banashi: A miniature toy-book from Japan. Tokyo: Ise-Tatsu. Asian Children’s Literature Collection, National Library, Singapore. (Call no.: RCLOS 895.63 HER).

Another gem is the visually arresting Pang Tao (Flat Peaches): Eight Fairies Festival (c. 1900–1950)33 about a legendary group of deities. Bound in an accordion format and containing 10 beautifully hand-coloured illustrations framed in silk brocade, this bilingual title in English and Chinese is available in the ACL Collection.

This book bears witness to how much the physical form of the book has evolved. Early books in China were made of narrow strips of bamboo tied together in a bundle using either silk or leather. Silk later replaced bamboo as a writing material and was rolled around rods like a scroll. With the invention of paper, books were made by folding a long strip of paper accordion-style.34

In the decades that followed, the ACL Collection has been redefined to concentrate on material written in the four official languages of Singapore, and aimed at children and young adults up to 14 years old. Comprising picture books, fiction and non-fiction as well as reference books, the collection includes titles from Southeast Asia, East Asia, Central Asia and West Asia.35

The ACL Collection aspires to captivate, inform and foster awareness among readers and researchers of Asia’s rich cultural and literary heritage. The books in the collection, which number more than 12,000, are available for reference on Level 9 of the National Library Building.

Stories from Asia: The Asian Children’s Literature Collection presents highlights from the collection held in the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library. The collection, over 12,000-strong, is located on level 9 of the National Library Building. This full-colour hardcover book sheds light on the literary and historical developments in children’s literature about Asians and Asia. Apart from featuring unique and rare items from the collection, it also covers diverse topics such as the power of storytelling and imagination, Asian folktales, foreign perspectives of Asia and emergent Asian children’s literature. The collection is recognised by UNESCO as one of the “nationally and internationally significant library collection”.

The book is available for reference at the Lee Kong Chian Reference Library and for loan at selected public libraries (Call nos.: RSING 809.89282 STO and SING 809.89282 STO) as well as for digital loan at nlb.overdrive.com.

Goh Yu Mei is a Librarian at the National Library, Singapore, working with the Chinese Arts and Literary Collection. Her research interest lies in the interaction between society and Chinese literature.

Goh Yu Mei is a Librarian at the National Library, Singapore, working with the Chinese Arts and Literary Collection. Her research interest lies in the interaction between society and Chinese literature.

Michelle Heng is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She has curated a tribute showcase, “Edwin Thumboo – Time-travelling: A Poetry Exhibition” in 2012, and compiled and edited an annotated bibliography on Edwin Thumboo, Singapore Word Maps: A Chapbook of Edwin Thumboo’s New and Selected Place Poems (2012) as well as the Selected Poems of Goh Poh Seng (2013).

Michelle Heng is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She has curated a tribute showcase, “Edwin Thumboo – Time-travelling: A Poetry Exhibition” in 2012, and compiled and edited an annotated bibliography on Edwin Thumboo, Singapore Word Maps: A Chapbook of Edwin Thumboo’s New and Selected Place Poems (2012) as well as the Selected Poems of Goh Poh Seng (2013).

RELATED ARTICLES

NOTES

-

李想 [Li, X.]. (2000).《花木兰》[Hua Mulan] (p. 18). Singapore: Newton Publications. (Call no.: Chinese RAC 398.20951 LX-[FOL]) ↩

-

Dong, L. (2006, April). Writing Chinese America into words and images: Storytelling and retelling of the song of Mu Lan. The Lion and the Unicorn, 30 (2), 218–233, p. 219. Retrieved from ProQuest Central via NLB’s eResources website. ↩

-

The period that followed the Eastern Jin dynasty (东晋, 317–420) and before the establishment of the Sui dynasty in 581 is commonly referred to as the Northern and Southern dynasties (南北朝). The Southern Dynasties (420–589) referred to the four dynasties, namely Song (宋), Qi (齐), Liang (梁) and Chen (陈), which ruled the southern part of China from Jiankang (建康, modern-day Nanjing). In contrast, the northern part of China was in a state of war from 304 to 439 [known to historians as the era of Sixteen Kingdoms (十六国)] until the Tuoba clan of the Xianbei established the (Northern) Wei dynasty ((北)魏) and conquered the most part of northern China. The regime under the Tuoba clan was short-lived and northern China was ruled under different clans and factions, each establishing their own dynasty. These dynasties were collectively referred to as the Northern dynasties. For more details, see Ebrey, P.B. (1996). The Cambridge illustrated history of China (pp. 89–93). Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. (Call no.: R 951 EBR) ↩

-

For more details on the different versions of Mulan in different periods in the history of China, see Lan, F. (2003, Summer). The female individual and the empire: A historicist approach to Mulan and Kingston’s woman warrior. Comparative Literature, 55 (3), 229–245. Retrieved from JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website; Edwards, L. (2016). Women warriors and wartime spies of China (pp. 17–39). Cambridge, United Kingdom; New York, New York: Cambridge University Press. (Call no.: 355.0092 EDW); Yang, Q. (2018). Mulan in China and America: From premodern to modern. Comparative Literature: East & West, 2 (1), 45–59. Retrieved from Taylor & Francis Online website. ↩

-

Yang, 2018, pp. 49–50. ↩

-

Kingston, M.H. (1989). The woman warrior: Memoirs of a girlhood among ghosts. London: Picador. (Call no.: 305.8951073 KIN) ↩

-

Lee, J.M. (1995). The song of Mu Lan. Arden, North Carolina: Front Street. (Call no.: RAC 895.1 MUL-[ACL]) ↩

-

Zhang, S.N. (1998). The ballad of Mulan. Union City, California: Pan Asian Publications. (Call no.: 398.220951 ZHA-[FOL]) ↩

-

李想 [Li, X.]. (1998).《花木兰》[Hua Mulan]. Singapore: Newton Publications. (Call no.: Chinese RAC 398.2095102 HML-[FOL]); 李想, 2000. ↩

-

San Souci, R.D. (1998). Fa Mulan: The story of a woman warrior. New York: Hyperion Books for Children. (Call no.: RAC 398.2 SAN-[ACL]) ↩

-

永春 [Yong, C.]. (2002).《花木兰》[Hua Mulan]. Singapore: 新亚出版社. (Call no.: Chinese RAC C813.4 YC); Wang, Z. (2020, July). Cultural “authenticity” as a conflict-ridden hypotext: Mulan (1998), Mulan Joins the Army (1939) and a millennium-long intertextual metamorphosis. Arts, 9 (3), 78. Retrieved from MDPI website. ↩

-

Li, J. (2014). Mulan: A story in English and Chinese. New York: Better Link Press. (Call no.: RAC 398.2 JIA-[ACL]) ↩

-

Gang, Y., & Xiao, G. (2007). The story of Mulan: The daughter and the warrior. Beijing: China Intercontinental Press. (Call no.: RAC 398.2 YI-[FOL]) ↩

-

雅瑟 & 苏阳 [Ya, S., & Su, Y.]. (2012).《中华句源: 品味文化精髓, 感受传世经典》[Zhonghua juyuan: Pinwei wenhua jingsui, ganshou chuanshi jingdian] (p. 202). Beijing: Beijing Book Co. Inc. (Call no.: Chinese 810.07 YS); Lee, C.Y. (2004). Emperor Chengzu and imperial filial piety of the Ming dynasty: From the classic of filial piety to the biographical accounts of filial piety. In A.K.L. Chan & S.-H. Tan (Eds.). (2004). Filial piety in Chinese thought and history (pp. 144–151). London: RoutledgeCurzon. (Call no.: R 173 FIL) ↩

-

Wong, R. (2016). Introduction: The power of stories (pp. 11–15). In Stories from Asia: The Asian Children’s Literature Collection. Singapore: National Library Board. (Call no.: R 809.89282) ↩

-

Hearn, L., & Hodges, M. (1989). The voice of the great bell. Boston: Little, Brown & Company. (Call no.: RCLOS 398.20951 HOD) ↩

-

San Souci, D. (1999). In the moonlight mist: A Korean tale. Honesdale, PA: Boyds Mills Press. (Call no.: RAC 398.209519 SAN-[ACL]) ↩

-

Uchida, Y. (1994). The wise old woman. New York: Margaret K. McElderry. (Call no.: RAC398.20952 UCH-[ACL]) ↩

-

Young, E. (2004). I, Doko: The tale of a basket. New York: Philomel Books (Call no.: RAC 813.54 YOU) ↩

-

Stories from Asia: The Asian children’s literature collection, 2016, pp. 22–25. ↩

-

Stories from Asia: The Asian children’s literature collection, 2016, p. 24. ↩

-

Stories from Asia: The Asian children’s literature collection, 2016, p. 25. ↩

-

Stories from Asia: The Asian children’s literature collection, 2016, p. 25. ↩

-

Herring, A., & Hirose, T. (1969). Otogi-Banashi: A miniature toy-book from Japan. Tokyo: Ise-Tatsu. (Call no.: RCLOS 895.63 HER) ↩

-

Stories from Asia: The Asian children’s literature collection, 2016, pp. 132–133. ↩

-

蟠桃八仙會 = Pang tao (Flat peaches), Eidht [i.e. Eight] Fairies Festival, a festival held on the 3d [i.e. 3rd day] of the 3d [i.e. 3rd] lunar month in honor of the Goddess Hsi Wang mu. (c. 1900–1950). China: [s.n.]. (Call no.: RCLOS 398.0951 PAN) ↩

-

Stories from Asia: The Asian children’s literature collection, 2016, pp. 142–143. ↩

-

Stories from Asia: The Asian children’s literature collection, 2016, p. 26. ↩