Urang Banjar: From South Kalimantan to Singapore

Zinnurain Nasir and Nasri Shah shed light on the Banjar people, a small but significant sub-ethnic Malay community from Borneo.

Haram manyarah waja sampai kaputing is a traditional phrase in basa Banjar, or Banjarese, the native language of the Banjar people (Urang Banjar)1 who originally hailed from South Kalimantan on the island of Borneo.

Literally translated as “Let not the steel [of a blade] stop short until its very point”, the imagery of steel and blade recalls the Banjar community’s martial history, beginning with the local sultanate’s skirmishes with Dutch and British traders in the 17th century right up to the Banjarmasin War of 1859.2

In the context of modern Singapore, the phrase is about persistence, about never giving up. In the words of former Malay-language teacher and a Banjar, Mohd Gazali bin Mohd Arshad, whose uncle Haji Mohamed Sanusi was the first Mufti of Singapore and also a Banjar, “… haram manyarah waja sampai kaputing. If we [are] to do anything, let us do it well… achieve and complete it well”. The phrase continues to be used today by the Banjar communities in cities such as Banjarmasin (now the capital city of South Kalimantan) and Martapura.

This phrase also greeted visitors to the “Urang Banjar: Heritage and Culture of the Banjar in Singapore” exhibition held at the Malay Heritage Centre from 28 November 2020 to 25 July 2021.3 The exhibition showcased the many ways in which Banjar culture has been localised since the arrival of the first Banjar people to Singapore in the 19th century, including the importance of the phrase as a rallying call for the community.

The Banjar community is one of the smallest sub-ethnic Malay communities in Singapore. In the 1990 Census of Singapore, only 12 people identified themselves as Banjarese.4 (Since then, the census has stopped publishing the numbers for sub-ethnic groups so updated figures are not available.)

What is believed to be the first documented count of the Banjarese community in Singapore dates to the 1911 Report on the Census of the Colony of the Straits Settlements. The census recorded that there were 377 Banjar individuals here, making up about 0.64 percent of the total population of Malays at the time.5

Pioneering Migrants

Members of the Banjar community in Singapore are able to trace their lineage to traders, diamond merchants, businessmen and travellers who arrived here from South Kalimantan via overland routes in the Malay Peninsula or by sea from as early as the beginning of the 19th century.

Merantau encapsulates the reasons and motivations behind migration within the Malay world – from the early groups of sojourners during ancient times to present-day travellers. The term is traditionally associated with the Minangkabau community of West Sumatra, whose matrilineal practices prompted young men to seek subsistence and fortune in other lands. However, merantau has also become a common practice and way of life for other communities and sub-ethnic groups in the Malay world, including the Urang Banjar.

Landak and Pontianak in West Kalimantan; Perak and Batu Pahat in the Malay Peninsula as well as Singapore are just some towns and cities that the Banjar community migrated to.

The first large-scale wave of migration is thought to have occurred in the 1780s. People moved from Banjarmasin to Sumatra as a result of conflict between the sultan at the time, Sunan Nata Alam, and a prince named Pangeran Amir.6 A little less than a century later, the outbreak of the Banjarmasin War prompted a further exodus of the Banjar people to Malaya and Singapore.

But the story of migration of the Banjar community across the Malay Archipelago is framed not only in terms of conflict; it was also as a quest for new opportunities and life experiences. The numerous towns and cities in the Malay world afforded these migratory Banjar many options and it was just a matter of deciding which locale would best suit their needs. True to the aforementioned Banjar phrase, conflict and crisis failed to dampen the Banjar community’s spirit and resilience in persevering till the end (waja sampai kaputing).

The Banjar with ties to royalty and the nobility, as well as those with links to the diamond industry, such as diamond traders and merchants, flocked to Landak in West Kalimantan which had built up a reputation as a diamond mining district from the 18th century. By 1858, the diamond trade in Landak was predominantly in the hands of the Banjar community.

The Banjar people also regarded Landak as a safe haven since the Sultanate of Landak was allied with the Sultanate of Banjar. The increasing Dutch presence in South Kalimantan, coupled with the Banjarmasin War and the subsequent abolition of the Sultanate of Banjar in 1860, prompted a wave of migration.

Perak, on the western coast of the Malay Peninsula, was another destination for the Banjar people.7 The state had fertile land similar to the area surrounding the Barito River in South Kalimantan. The flooding that occurred around this river in the late 1880s prompted a mass movement of the Banjar people to Krian (Kerian) in the northwestern corner of Perak.

These migratory and settlement patterns would be replicated when the Urang Banjar migrated to Singapore. In 1824, the Dutch colonial government re-established Banjarmasin as a free port, which meant that cargo ships could ply routes to non-Dutch-controlled ports, including Singapore.8 Trade between both cities primarily consisted of textiles, including muslins, gurrahs and blatchu cloth, among others.9

Some of the earliest documented Banjar merchants emigrated to Singapore from the mid-19th century onwards, including Haji Mahmood bin Abdul Rahim and Haji Osman bin Haji Abu Naim, who became successful diamond traders and prominent members of the local Banjar community. Haji Mahmood owned a large house spanning Lorongs 18 and 20 Geylang, one of several abodes reserved for his extended family of three wives and 18 children.10

By the turn of the 20th century, passenger ships began to ply regularly between Singapore and Banjarmasin, indicating a high demand for travel to these two destinations. In 1907, shipping companies were advertising first-class passenger routes from Singapore to Banjarmasin.11

Due to the ease of travelling between the two cities, more Banjar people began arriving in Singapore and they soon established a small but significant presence in the local landscape.

Singapore’s Banjar Community

In Singapore, Banjar families and businesses established themselves in places like Kampong Gelam (Glam) and various locations in the eastern part of the island.

Kampong Gelam

Within Kampong Gelam there was a “Kampong Intan” (Diamond Kampong), said to be named after the Banjarese gemstone merchants and jewellery shops operating there in the late 19th century. According to oral histories and anecdotes, this kampong was located along present-day Baghdad Street.12

It is believed that there was another area in Kampong Gelam known as “Kampong Selong” (Ceylon Kampong), where Ceylonese gemstone traders plied their trade, and together with the Banjar merchants, formed a thriving ecosystem where customers could purchase ready-made jewellery or even procure raw diamonds to be set into customised one-of-a-kind pieces. However, this diamond trade by the Banjar and Ceylonese likely declined after the Japanese Occupation (1942–45), most probably due to the increasing demand for African diamonds whose trade was controlled by the Europeans.

Sisters Fauziah and Faridah Jamal recalled that their family’s diamond trading business and polishing workshop were located on Jalan Pisang (as was their home). Their late father, Haji Ahmad Jamal bin Haji Mohd Hassan, who was also a trustee of Sultan Mosque, was said to be one of a few, if not the only, Banjar diamond cutters and artisans living and working in the area in the early 20th century.

Said Fauziah Jamal: “We had our neighbours – a goldsmithing workshop, an old Chinese man who would be working on these pieces of jewellery, mostly gold pieces, and then we had my uncle who’s working across the road… we had also another granduncle who had an office further down this road. Basically [Jalan Pisang] is where the activity of the diamond trade used to be.”13

Sumbawa Road

Not so far away, near the intersection of today’s Jalan Sultan and Victoria Street or North Bridge Road is said to be the site of a former club called the Darul Ta’alam Club, founded in 1893. A photo of this club, located along the now expunged Sumbawa Road, depicts several well-dressed men, some of whom are presumably Banjar businessmen and merchants, gathered in front of a building with “Darul Ta’alam 20th Anniversary 15th Nov 1913” inscribed on its facade.

The origins of the club and the identity of its founders are unclear. But by the time the photo was taken in 1913, the club was well patronised by merchants and individuals from other sub-ethnic Malay groups.

Besides serving as the headquarters for a football club of the same name, the Darul Ta’alam Club was also the venue for other social and communal gatherings, including serving as the main meeting place for organisations such as the Kesatuan Melayu (Malay Union). The building has since been demolished.

Geylang

As Geylang became a thriving residential and commercial centre in the 19th century, several Banjar merchants acquired property in the area, including the diamond trader Haji Mahmood bin Abdul Rahim.

Many newly arrived Banjar also made Geylang their home, such as the father of Haji Ahmad Jamal bin Haji Mohd Hassan (the grandfather of sisters Fauziah and Faridah Jamal) who lived at 681 Geylang Road. There were also other Banjar families residing at Lorongs 26 and 35 Geylang.

However, Geylang may have been more than just a centre for the Banjar community to live though. The evidence comes from a 1937 lithographed manuscript titled Kitab Perukunan Sembahyang Sheikh Arsyad (Sheikh Arsyad’s Book of Commandments Pertaining to Prayer), which consolidates the writings of a famous Banjar religious scholar. In the frontispiece, the publisher indicates that the book was printed at 242 Lorong Engku Aman in Geylang, although the name of the publishing company is not mentioned.

Kembangan

Lorong Marican in Kembangan was home to Haji Arshad bin Haji Mahmood, the father of Mohd Gazali bin Mohd Arshad. “This house [at Lorong Marican] represented a house rich with history,” said Mohd Gazali. “That was where my uncles gathered… to speak to my father and reminisce about their father and grandfather. It was only much later that I realised that it was because of who my grandfather [the diamond trader Haji Mahmood] was.”14

The house was designed as a rumah panggung, a traditional house form built on stilts found in South Kalimantan, and similar housing were also once commonly seen on adjacent roads like Lorong Marzuki.

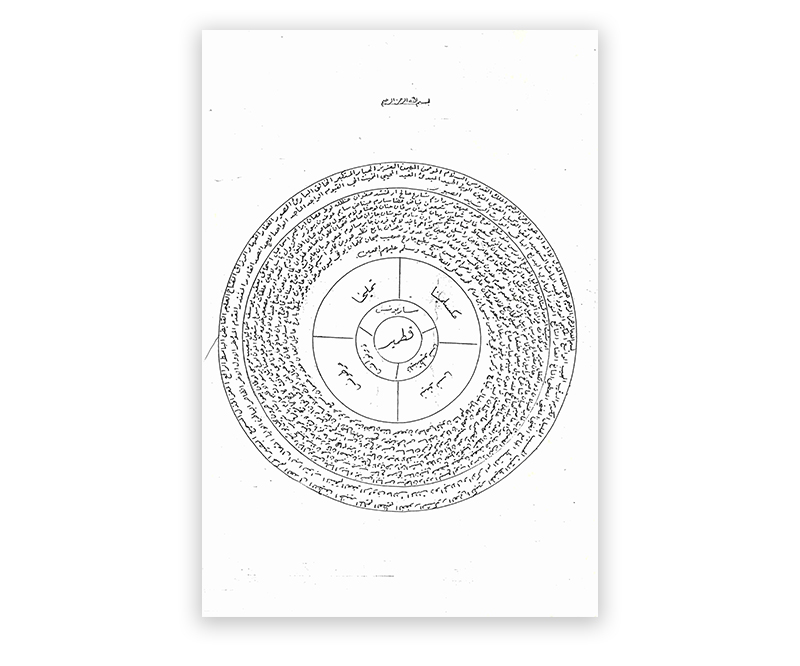

Hanging in Haji Arshad’s home was a mandala-shaped diagram called the ayat pendinding, consisting of text written in Arabic. The text comprises words of prayers, composed specifically to protect a house and its occupants. The ayat pendinding was designed and made by Haji Arshad, and members of the Banjar community who visited Haji Arshad’s home for religious classes would request copies of these ayat pendinding from him to be displayed in their own homes.

Kampong Banjar

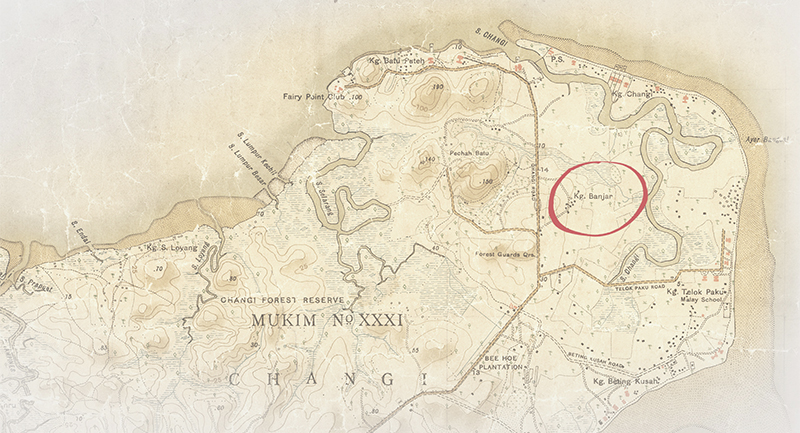

In addition to the communities living in traditional Malay settlements like Geylang and Kembangan, there is also evidence of Banjar settlements by the coast. A 1924 map lists a “Kampong Banjar” along Changi Road.15

Although no existing members of the Banjar community today are familiar with this kampong, an account in the Berita Harian newspaper in 1987 by Kahar bin Kurus, 71, who once lived in the Changi area, describes life in the kampong. According to him, Kampong Banjar and the neighbouring kampongs were once thriving villages inhabited by various sub-ethnic Malay groups, including the Banjarese. The villagers, who earned a living primarily from fishing, lived in close-knit communities and held frequent gatherings to celebrate their small successes and muse over their daily affairs. “Para penduduk di situ juga sering mengadakan majlis-majis keramaian dua tiga kali dalam setahun untuk menghiburkan hati setelah berpenat-lelah bekerja,” he said. (“The villagers frequently hosted gatherings, at least two to three times a year, to reward themselves for their hard work.”)16

These gatherings parallel an activity that the Banjar community today refers to as arul ganal, which means “big gatherings”, a cultural event that is commonly held in South Kalimantan. Unfortunately, this kampong was expunged prior to World War II, and in a 1945 map, this site appears to have made way for Changi airfield.

The displaced inhabitants of Kampong Banjar moved south to nearby villages, notably Kampong Beting Kusah, Kampong Telok Paku and even to Kampong Ayer Gemuroh, at what is today’s East Coast Park.17

In the 1970s, Kampong Ayer Gemuroh suffered a similar fate as Kampong Banjar and also had to make way for the expansion of Changi airfield.18 The Banjar people were resettled into high-rise flats and the kampong was expunged.

While estimates are not available, the number of people who identify as being Urang Banjar in Singapore today is likely to be very small. However, no one should underestimate what the Urang Banjar, regardless of their numbers, are capable of. Haram manyarah waja sampai kaputing is still very much a part of what being a Banjar means today, and speaks to the determination of the Banjar people to face every challenge and to never give up, no matter the odds.

Zinnurain Nasir is an Assistant Curator with the Malay Heritage Centre. His interests include community histories, local and regional identity histories and charting cultural practices. He is currently researching Jawi publications as a medium to represent post-World War II community landscapes.

Zinnurain Nasir is an Assistant Curator with the Malay Heritage Centre. His interests include community histories, local and regional identity histories and charting cultural practices. He is currently researching Jawi publications as a medium to represent post-World War II community landscapes.

Nasri Shah is a Curator with the Malay Heritage Centre. His past projects include “Mereka Utusan” (2016) and “Women in Action” (2018), which focused on histories of the Malay publishing industry and women’s rights movement respectively.

Nasri Shah is a Curator with the Malay Heritage Centre. His past projects include “Mereka Utusan” (2016) and “Women in Action” (2018), which focused on histories of the Malay publishing industry and women’s rights movement respectively.

NOTES

-

In the Banjarese language, the Indonesian word “orang” for “person” is pronounced as “urang”. ↩

-

The Banjarmasin War (1859–63) was a succession war in the Sultanate of Banjarmasin as well as a colonial war fought for the restoration of Dutch authority in the eastern and southern parts of Borneo. ↩

-

The digital companion to the exhibition can be accessed from the National Heritage Board’s Roots website: https://www.roots.gov.sg/stories-landing/stories/Urang-Banjar ↩

-

Tham, S.C. (1993). Defining “Malay”. Singapore: Department of Malay Studies, National University of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING 305.899205957 THA). [Note: This number is only representative of people who indicated themselves as “Banjarese” on their own accord. The actual number of people with Banjarese ancestry might be far higher.] ↩

-

Marriott, H. (1911). Report on the census of the Colony of the Straits Settlements, taken on the 10th March, 1911. Singapore: Printed at the Government Printing Office. (Call no.: RRARE 312.095957 STR; Microfilm no.: NL5646) ↩

-

For more information, see Ahmad Fakhri Hutauruk. (2020). Sejarah Indonesia: Masuknya Islam hingga kolonialisme (pp. 77–78). Indonesia: Yayasan Kita Menulis. (Not available in NLB holdings); Haiqal Halim. (2019, May 14). Penghijrahan orang Banjar ke Malaysia. M-Update. Retrieved from M-Update website. ↩

-

Potter, L. (1993). Banjarese in and beyond Hulu Sungai, South Kalimantan: A study of cultural independence, economic opportunity and mobility (pp. 264–296). In J.T. Lindblad (Ed.), New challenges in the modern economic history of Indonesia: Proceedings of the first conference on Indonesia’s modern economic history, Jakarta, October 1–4, 1991. Leiden: Programme of Indonesian Studies. (Call no.: RCLOS 330.9598 CON) ↩

-

Rochwulaningsih, Y., Noor Naelil Masruroh & Fanada Sholihah. (2019, December). Tracing the maritime greatness and the formation of cosmopolitan society in South Borneo. Journal of Maritime Studies and National Integration, 3 (2), pp. 71–79. Retrieved from ResearchGate website. ↩

-

Exports. (1833, March 7). Singapore Chronicle and Commercial Register, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Saudagar kaya dengan niaga intan berlian. (1981, December 8). Berita Harian, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Steamer sailings. (1907, October 2). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Karim Iskandar. (2011, February 16). Kisah amuk di Kg Intan. Berita Harian, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Rossman Ithnain. (2014, July/August). Popular Malay jewellery in the 1950s and 1960s. Passage. Retrieved from Singapura Stories website. Note: The location of the former Diamond Kampong has also been suggested to be at the site now occupied by Raffles Hospital. See Imran Tajudeen. (2005). Reading the traditional maritime city in Southeast Asia: Reconstructing the 19th century port town at Gelam-Rochor-Kallang, Singapore. Journal of Southeast Asian Architecture, 8, pp. 1–25. (Call no.: RSING q720.95 JSAA) ↩

-

National Heritage Board. (2021, March 16). Urang Banjar: Heritage and culture of the Banjar in Singapore. Retrieved from Roots website. ↩

-

National Heritage Board, 16 Mar 2021. ↩

-

Survey Department, Singapore. (1924). Singapore Sheet No. 8: Mukim Number: XXVII Bedok, XXVIII Ulu Bedok, XXIII Paya Lebar, XXII Saranggong, XXX Teban, XXIX Tampines, XXXI Changi, XXI Punggol [Map]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Hanim Mohd Salleh. (1987, September 10). Zaman ke laut dengan lampu colok. Berita Harian, p. 3. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Housing problems in Singapore kampongs. (1948, July 3). The Malaya Tribune, p. 1; Rural Malays’ grievances. (1948, June 16), The Malaya Tribune, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Kampong Ayer Gemuroh turut beri jalan kpd projek pembangunan. (1974, November 21). Berita Harian, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩