Vaccinating a Nation

The history of vaccination in Singapore goes back to the days of William Farquhar. Ong Eng Chuan provides an overview of vaccination efforts to prevent epidemics from breaking out here.

The ongoing Covid-19 pandemic has cast vaccination into the spotlight in the fight against the disease and to reduce its spread. Vaccination is not a new phenomenon in Singapore though. Most children here are routinely vaccinated against diseases such as measles and mumps.

Vaccinations for children are carried out under the National Childhood Immunisation Schedule overseen by the Ministry of Health. It covers diseases such as tuberculosis, diphtheria, hepatitis B, measles, pertussis (whooping cough), pneumococcal infection, poliomyelitis, rubella (German measles) and tetanus. Vaccination does not stop with children either. Many adults take the influenza (flu) vaccine, especially before travelling to colder climates, as well as the pneumococcal and hepatitis B vaccines. The elderly and people with certain chronic conditions are strongly advised to have the flu jab regularly as well.

The highly organised way in which the Health Ministry handles the programme for childhood vaccinations makes it seem like a modern medical practice. However, vaccination in Singapore actually has a long history. The very first vaccine – for smallpox – was introduced as early as 1819.

Smallpox and Vaccination in Early Singapore

Until fairly recently, smallpox, which is caused by the variola virus, was a much-feared disease. It was highly contagious, had a high mortality rate and those who survived were often disfigured for life. Thanks to a concerted global vaccination campaign, smallpox was eventually eradicated and on 8 May 1980, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the world free of the disease.1

The first step towards eradicating smallpox began in 1796 when English doctor Edward Jenner used cowpox (a milder form of smallpox) to induce immunity against the more virulent smallpox.2 This smallpox vaccine was the first vaccine to be introduced in Singapore.

In December 1819, the Resident of Singapore William Farquhar wrote to officials in Penang to request for supplies of the smallpox vaccine.3 The vaccine was sent to Singapore and a Vaccine Department set up to administer the vaccination. However, this early attempt at a vaccination programme failed and the Vaccine Department was abolished in 1829. Subsequent efforts also produced erratic outcomes and as a result, smallpox remained prevalent in Singapore. In 1838, for example, a smallpox epidemic claimed hundreds of lives.4

These early vaccination programmes faltered due to resistance from the local population.5 Few residents came forward to be vaccinated and parents were unwilling to send their healthy children to be vaccinated for fear of putting them at risk.

Back then, vaccination was done using arm-to-arm transfer, i.e. getting pustular material from one vaccinated person to directly inoculate another person by scratching the material into the recipient’s arm.6 This method needed a constant stream of people to help propagate the vaccine.

It was also difficult to obtain fresh vaccine lymph or material when the supply ran out. As Penang and Singapore did not produce the smallpox vaccine, fresh material had to be shipped from Calcutta.7 However, the tropical climate made it difficult to maintain the shelf life of the vaccine so by the time the vaccines arrived here, their effectiveness have been compromised. The authorities made attempts to obtain vaccine lymph from other sources such as Batavia (now Jakarta) and the Royal Jennerian Institute in London (which would take six weeks to reach Singapore by ship), in the hope that these would give better results.8

In 1863, when the incidence of smallpox increased again, the government was urged to take tougher measures, including making vaccination compulsory by law, following in the footsteps of the Dutch who had successfully introduced compulsory vaccination in the Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia).9

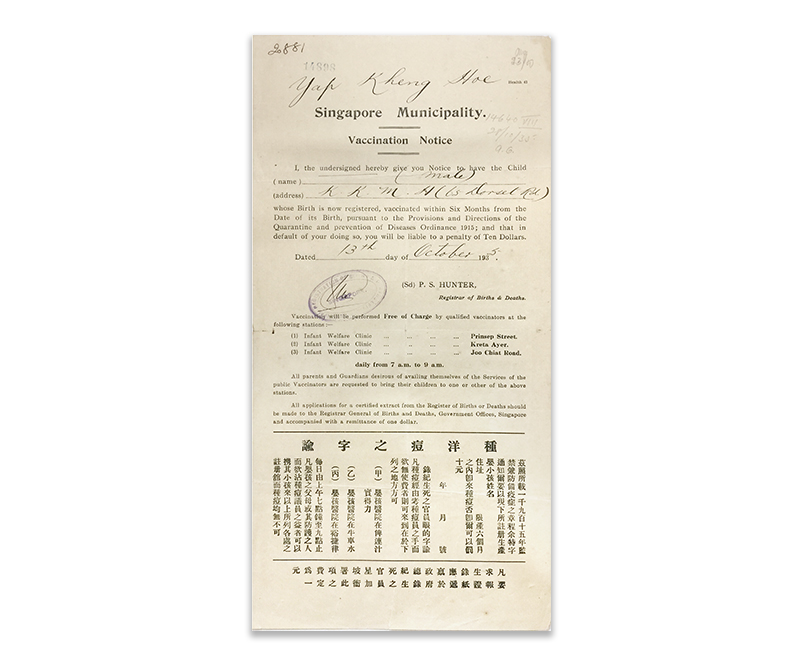

Stricter public health control measures were finally introduced after the Straits Settlements became a Crown Colony in 1867. The Quarantine Ordinance was passed by the Legislative Council in June 1868, followed by An Ordinance to Extend and Make Compulsory the Practice of Vaccination, which came into effect on 1 May 1869.10

The latter legislation led to the Ordinance for Registration of Births and Deaths of 1868. This was a necessary move to keep track of the number of children who were being vaccinated as well as the overall death rate in the population. It would also allow the authorities to study the causes of death and gauge the success of the islandwide vaccination programme.11 In addition, the Registrar of Births and Deaths was also responsible for notifying all parents to vaccinate their newborn babies.

Smallpox continued to be a problem in Singapore up until the 1950s. After WHO declared the virus eradicated, Singapore amended the legislation so that smallpox vaccination would no longer be required by law from March 1982.12

BCG and the Battle Against Tuberculosis

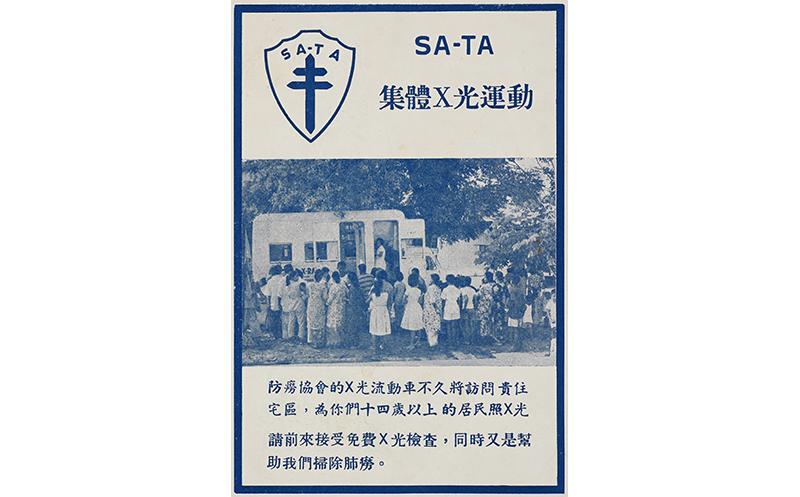

At the end of World War II, Singapore found itself in another battle, this time against tuberculosis (TB). TB is an infectious disease caused by the Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria. There are two types of TB infections – latent TB infection and TB disease. People with the former are asymptomatic and cannot spread the bacteria whereas people with the TB disease may infect others. If left untreated, TB can be fatal.13

In the aftermath of the Japanese Occupation (1942–45), the incidence of tuberculosis increased sharply, especially among young children. In fact, it was the number one killer disease right up to the 1960s.14

The anti-tuberculosis vaccine, Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), had been developed by French scientists Albert Calmette and Camille Guérin in 1919. However, the vaccine only gained wider acceptance after studies providing evidence of its efficacy were conducted in the 1940s.15

The first large-scale BCG vaccination in Singapore was not carried out by government health authorities though. Instead, it was conducted by the Singapore Anti-Tuberculosis Association (SATA), a charity organisation. The idea of forming an organisation to fight TB had come from a group of prisoners-of-war interned at Changi Prison and Sime Road Camp during the Occupation years. Eventually, a group of doctors and philanthropists banded together to form SATA in 1947.16

While government health officials were still reviewing the BCG vaccine, SATA, under its first medical director, G.H. Garlick, believed that providing children with protection against TB was an urgent task that could not wait.17

After obtaining a small consignment of the BCG vaccine from the Pasteur Institute in Paris, SATA launched its immunisation programme on 28 June 1949 by vaccinating 21 children.18 As new consignments of the vaccine began to arrive more regularly, SATA ramped up its vaccination drive.19

Two years later, the government’s pilot BCG vaccination programme under the auspices of the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) began. In June 1951, a UNICEF team started conducting tests on pupils of the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus on Bras Basah Road, with the aim of eventually vaccinating the majority of the 130,000 schoolchildren in Singapore within four months. That same year, inoculations of newborns began but these were discontinued in 1952 due to the “lack of staff to do follow-up work”.20

By 1956, the Singapore government realised that administering the BCG vaccine to children at school entrance age was too late as statistics showed that many children had been infected even before starting school. In December that year, the Health Ministry announced that all babies in Singapore would be given the BCG vaccine soon after birth. SATA’s medical director Garlick approved of this move. “The younger a child is inoculated the better,” he said. “T.B. is so rife here that many children become infected at a very early age.”21

Between 1956 and 1972, over one million vaccinations had been performed. It was estimated that more than 90 percent of infants and primary school students and 75 percent of secondary school students had been inoculated against TB by 1972.22 Students used to get booster jabs at age 12 or 16 but this was discontinued in 2001 as there was no scientific evidence that it was necessary.23

TB remains a global public threat and is still endemic in Singapore, with a higher proportion of the elderly contracting the disease. In 2020, there were 1,370 new cases of active TB among Singapore residents, slightly lower than the 1,398 cases the year before.24

Polio, Diphtheria, Measles and Rubella

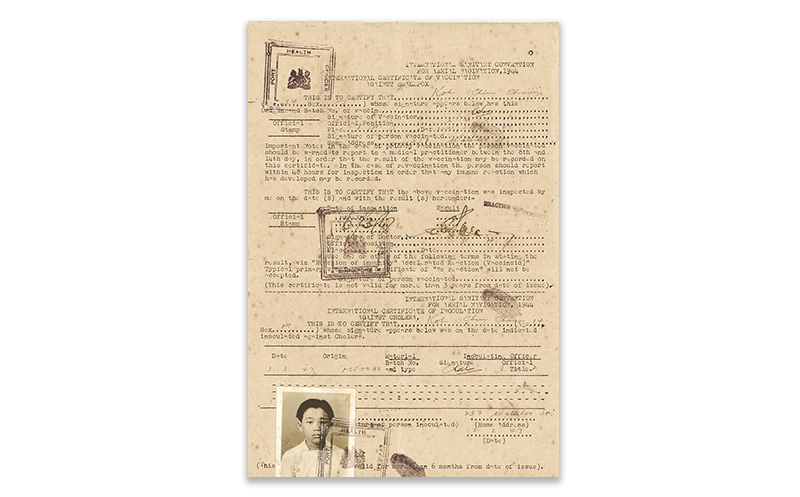

During the post-war period, Singapore also had to deal with poliomyelitis, or polio, a crippling and life-threatening disease caused by the poliovirus. The virus is highly contagious and can infect a person’s spinal cord causing paralysis and even death. Although the disease affects people of all ages, infants and children are particularly vulnerable.25

A major polio outbreak between August and December 1958 killed 12 and caused 404 infants and children to be crippled by the disease.26 As the number of polio cases continued to surge, there was added pressure on the government to act. Eventually, the Health Ministry decided to offer free polio vaccinations on a voluntary basis to children aged three to 10.

Between November and December 1958, over 200,000 children were immunised with the oral Sabin vaccine (named after its developer, Albert Bruce Sabin) in vaccination centres set up across the island.27 However, this did not stop another outbreak from happening just two years later which crippled 196 people.

After the first outbreak, the government convened a committee to address the problem. The committee recommended vaccinating all children from birth to school-entry age. The government approved the recommendation and the immunisation programme began with a mass campaign in 1962, when children up to 6 years old were vaccinated.

This led to a significant decline in the incidence of paralytic polio and polio cases in the following decade.28 By 1975, a large segment of the population had been immunised. As a result, the circulation rate of the poliovirus among the community was decreased to such a low level that the chances of any person being infected and developing paralytic poliomyelitis had been “reduced to vanishing point”.29

Although Singapore was officially declared polio-free in 2000, vaccination against polio continued as the disease had not been eradicated worldwide. In 2019, some 1,000 Singapore athletes and officials heading to the Philippines for the SEA Games had to be vaccinated against polio when new cases were reported there, 19 years after the Philippines had been declared free of the disease.30

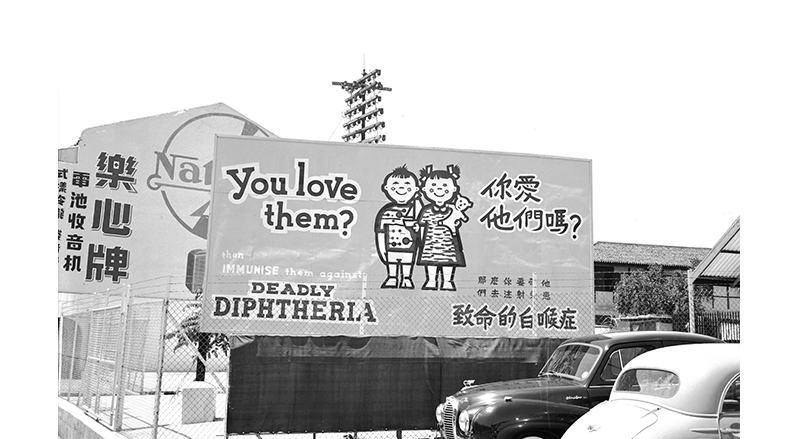

Another infectious and potentially dangerous disease is diphtheria which is caused by the Corynebacterium diphtheriae bacteria. Afflicted people experience common symptoms such as sore throat and fever but in severe cases, infection can lead to difficulty in breathing, heart failure, paralysis and even death.31 Vaccination against diphtheria was developed in the early 1920s and introduced in Singapore before World War II. After the Japanese Occupation, the government offered free vaccinations against diphtheria and other diseases such as pertussis (also known as whooping cough).32

However, the response to the government’s voluntary immunisation programme was lukewarm. Despite having no diphtheria epidemics in Singapore, the government decided to make diphtheria vaccination compulsory to reduce the number of increasingly isolated cases.

In 1961, the Legislative Assembly passed the Diphtheria Immunisation Ordinance making immunisation against diphtheria compulsory for all children under the age of one. Parents or guardians who failed to comply with the law would be liable to a fine not exceeding $500 for the first offence and $1,000 and/or jail of not more than a year for subsequent convictions. Free vaccination was offered at 27 maternal and children’s healthcare clinics.33

Today, diphtheria has been eradicated from Singapore although the disease is still endemic in many countries.34 In 2017, an isolated case of diphtheria occurred in Singapore when a Bangladeshi construction worker succumbed to the disease, the first local case in 25 years.35

By 1970, the Maternal and Child Health Services was providing a comprehensive programme of vaccination against tuberculosis, smallpox, poliomyelitis, diphtheria, whooping cough and tetanus through its network of 52 centres. In July that year, the government announced a new requirement that all children entering primary one in 1971 would have to be immunised against these infectious diseases.36

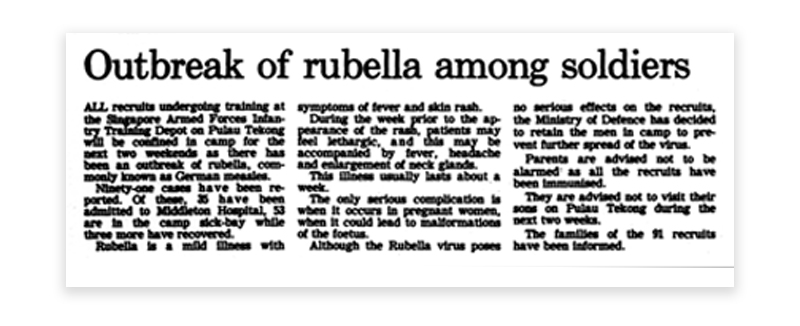

During the 1970s, due to frequent outbreaks of measles and rubella (also known as German measles), inoculation against these two diseases was introduced into the childhood vaccination programme.37

Measles is caused by the measles (rubeola) virus. Its symptoms include high fever, cough, watery eyes, and spots and rashes. But measles can be dangerous, especially for babies and young children as it may lead to serious complications such as pneumonia and encephalitis (inflammation of the brain).38

Rubella is caused by its namesake virus. Most people who are infected develop a mild illness, but as with measles, rubella can result in serious complications. It can cause infected pregnant women to miscarry or their babies to develop congenital birth defects.39

Measles vaccination was introduced in October 1976 while rubella vaccination for female primary school leavers was introduced a month later. However, many parents were still reluctant to vaccinate their children against measles because many held the traditional belief that it was good for children to get infected since it rids the body of “heat” or “cold” that causes rashes.40

Vaccination against the disease became compulsory by law on 1 August 1985. In January 1990, the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine replaced the separate jabs for measles and rubella. Although the three-in-one vaccine was more expensive, Acting Minister for Health Yeo Cheow Tong said that “for the child, having one shot is better than having three shots”. This injection would be administered to infants who were at least a year old.41

Hepatitis B Vaccine

In the 1970s, hepatitis B was a serious public health problem here. It was a disease that was endemic in Singapore and countries in the Asia-Pacific.42 The hepatitis B virus was first identified in the 1960s by American physician and geneticist Baruch S. Blumberg, who also developed the first vaccine for the disease. It soon emerged that this vaccine could help prevent a type of liver cancer called primary liver cancer.43 Studies showed that chronic hepatitis B carriers had a high risk of developing primary liver cancer, which was a common type of cancer in Singapore at the time. In 1979, Singapore had the highest incidence of primary liver cancer in the world.44

The association between hepatitis B and primary liver cancer fuelled a global race to produce the vaccine on a commercial scale. The Singapore government was also interested in the commercial production of the hepatitis B vaccine as the biotechnology industry was seen as an economically viable new sector. Unfortunately, Singapore’s vaccine production plan was eventually scrapped because the projected returns did not justify the $20 million investment required for the project.

Although the scheme to produce the hepatitis B vaccine in Singapore was derailed, the fight against hepatitis did not stop. In 1983, 600 medical staff from the Health Ministry and the National University of Singapore became the first to receive the hepatitis B vaccine. Due to the high cost, the vaccination programme targeted selected population groups who were at higher risk of acquiring the disease, such as babies of infected mothers, healthcare workers and national servicemen.45

On 1 September 1987, a vaccination-at-birth service was rolled out to inoculate all newborns in Singapore at a reduced fee. There were 140,000 hepatitis B carriers in Singapore at the time, and the government wanted to ensure that the disease would not spread to the rest of the population. Singapore was also one of the few countries in the world to make the hepatitis B vaccination available to all newborns.46

By 2000, more than 90 percent of infants had received the hepatitis B vaccination. While this age group was well protected against the disease, about half of Singapore’s adult population had no immunity against the virus. In 2001, the Health Ministry launched a four-year hepatitis B immunisation programme for students in secondary schools, junior colleges, centralised institutes, the institutes of technical education, polytechnics and universities.47

Since the introduction of this programme in Singapore, the annual incidence of acute hepatitis B infection has declined from eight cases per 100,000 population in 1987 to 3.6 per 100,000 population in 2000. The nation’s research findings and experience in implementing a national hepatitis B vaccination programme were shared internationally. In 2001, WHO also endorsed the long-term safety and efficacy of the hepatitis B vaccine and recommended that it be implemented in all endemic countries and for all newborns.48

Vaccinating Against Covid-19

As Singapore and the world struggle to contain the spread of Covid-19, vaccination has emerged as a key weapon in the fight.

Singapore has already begun vaccinating its population, having approved the emergency use of vaccines by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna. Vaccinations began in December 2020 and as at 17 July 2021, close to 2.7 million people have been fully vaccinated while around 4.1 million have received at least one dose.49

On 31 May 2021, the government announced that vaccines which have been approved for emergency use by WHO against Covid-19 could also be used in Singapore. At the moment, the list includes the vaccines by Johnson & Johnson, Sinovac and Oxford-AstraZeneca. This move will increase the pool of vaccines available for use here.50

As Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong said in his address to the nation on 31 May 2021, until a large proportion of Singapore’s population is vaccinated, more restrictions can then be lifted safely and gradually so that a semblance of normal life can return even as the virus becomes endemic here.51

Ong Eng Chuan is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore, where he manages the Rare Materials Collection. His research interest is in early Singapore publications.

Ong Eng Chuan is a Senior Librarian with the National Library, Singapore, where he manages the Rare Materials Collection. His research interest is in early Singapore publications.

RELATED ARTICLES

NOTES

-

World Health Assembly, 33. (1980). Declaration of global eradication of smallpox. Retrieved from World Health Organization IRIS website. ↩

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). History of smallpox. Retrieved from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. ↩

-

Lee, Y.K. (1973, December). Smallpox and vaccination in early Singapore (Part I) (1819–1829). Singapore Medical Journal, 14 (4), 525–531, p. 527. Retrieved from Singapore Medical Association website. ↩

-

Lee, Y.K. (1976, December). Smallpox in early Singapore (Part II) (1830–1849). Singapore Medical Journal, 17 (4), 202–206, p. 202. Retrieved from Singapore Medical Association website. ↩

-

Lee, Dec 1976, pp. 202–203. ↩

-

Belongia, E.A., & Naleway, A.L. (2003, April). Smallpox vaccine: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Clinical Medicine Research, 1 (2), 87–92, p. 88. Retrieved from NCBI website. ↩

-

The Royal Jennerian Institute was named after Edward Jenner. Lee, Y.K. (1977, March). Smallpox in early Singapore. (Part III) (1850–59). Singapore Medical Journal, 18 (1), 16–20, p. 16. Retrieved from Singapore Medical Association website. ↩

-

Lee, Mar 1977, p. 16; Lee, Y.K. (1977, June). Smallpox in early Singapore. (Part IV) (1860–1872). Singapore Medical Journal, 18 (2), 126–135, pp. 126–127. Retrieved from Singapore Medical Association website. ↩

-

Lee, Jun 1977, p. 129. ↩

-

The Vaccination Ordinance (No. 19 of 1868) was supplanted by the Quarantine and Prevention of Disease Ordinance (No. 33 of 1915). See Srinivasagam, E. (1972). Tables of the written laws of the Republic of Singapore, 1819–1971 (pp. 4, 40). Singapore: Malaya Law Review, University of Singapore. (Call no.: RSING q348.5957028 SRI) ↩

-

Lee, Jun 1977, p. 132. ↩

-

Smallpox jabs no more a must for kids. (1981, March 7). The Straits Times, p. 9; Smallpox vaccination papers not needed. (1981, March 7). The Business Times, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Basic TB facts. Retrieved from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. ↩

-

Lim, K.T., & Lee, M. (1997). Fighting TB: The SATA story, 1947–1997 (p. 14). Singapore: The Association. (Call no.: RSING 614.542095957 SIN); McKerron, P.A.B. [1947]. Annual report on Singapore for 1st April-–31st December 1946 (p. 70). (Call no.: RDLKL 959.57 MAC); Tuberculosis: Singapore’s no. 1 killer… (1957, February 11). The Singapore Free Press, p. 13; Cancer Society. (1964, December 10). The Straits Times, p. 12. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Luca, S., & Mihaescu, T. (2013, March). History of BCG vaccine. Maedica, 8 (1), 53–58. Retrieved from National Center for Biotechnology Information website; BCG prevents T.B. (1949, March 5). The Malaya Tribune, pp. VIII/I. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Lim & Lee, 1997, p. 18; SATA ComHealth. (n.d.). Our history and milestones. Retrieved from SATA ComHealth website; Vo. (1973, July 6). SATA tames a killer. New Nation, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Studying use of T.B. serum. (1949, February 1). The Singapore Free Press, p. 5; Flying anti-T.B. vaccine to S’pore. (1949, May 1). The Straits Times, p. 1; B.C.G. for kids: No decision yet. (1949, June 18). The Singapore Free Press, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

B.C.G. starts this week. (1949, June 12). Sunday Tribune (Singapore), p. 1; TB immunisation of children begins. (1949, June 29). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

2,000 children get anti-T.B. vaccination. (1949, October 13). The Malaya Tribune, p. 5; B.C.G. vaccination to start again. (1949, October 27). The Straits Times, p. 7; 1,500 Seletar boys get BCG serum. (1949, October 27). The Malaya Tribune, p. 2. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

B.C.G. team starts S’pore campaign. (1951, June 4). The Straits Times, p. 5; Vaccination for 130,000 children. (1951, June 4). The Singapore Free Press, p. 5; New campaign to halt TB. (1956, November 19). The Straits Times, p. 7. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

The Straits Times, 19 Nov 1956, p. 7; BCG vaccine for new-born babies. (1956, December 1). The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Chew, C.H., & Hu, P.Y. (1974, December). BCG programme in the Republic of Singapore. Singapore Medical Journal, 15 (4), 241–245, p. 241. Retrieved from Singapore Medical Association website. ↩

-

Just one anti-TB jab from now. (2001, June 28). The Straits Times, p. 21; One TB jab at birth. (2001, June 28). The New Paper, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ministry of Health Singapore. (2021, March 24). Update on tuberculosis situation in Singapore. Retrieved from Ministry of Health website. ↩

-

Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention. (n.d.). What is polio? Retrieved from Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention website; Ministry of Health. (n.d.).What all parents need to know about polio. Retrieved from Healthhub website. ↩

-

Colony of Singapore. (1959). Annual report 1958 (pp. 170–171). Singapore: Government Printing Office. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.57 SIN); Seah, H.K. (1995, April). World without polio. Healthscope, 5, 7. (Call no. RSING 362.1095957 H) ↩

-

Colony of Singapore, 1959, pp. 170–171; Lee, L.H., & Lim, K.A. (1977, March). Eradication of poliomyelitis in Singapore. Singapore Medical Journal, 18 (1), 34–40, pp. 37–38. Retrieved from Singapore Medical Association website. ↩

-

The number of paralytic polio cases went down from 78 cases in 1963 to four cases in 1968. In the subsequent years up to 1975, there were only five cases in total. Overall, the number of polio cases also decreased from 1,067 notified cases for the period 1954 to 1964 to 62 cases from 1965 to 1975. Not a single case was reported in 1969, 1970, 1974 and 1975. ↩

-

Lee & Lim, Mar 1977, pp. 35, 37–38. ↩

-

Wee, L. (2000, November 2). Singapore officially declared polio-free. The Straits Times, p. 42. Retrieved from NewspaperSG; Dancel, R. (2019, September 19). Polio, a menace eradicated in the Philippines 19 years ago, resurfaces. The Straits Times; Chia, N. (2019, November 24). Polio shots for Team S’pore athletes just before SEA Games. The Straits Times. Retrieved from The Straits Times website. ↩

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Diphtheria. Retrieved from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. ↩

-

Blakemore, W. L. (1941). Diphtheria and its prevention by immunisation. Singapore: Government Printing Office. (Call no.: RRARE 616.931305 BLA; Accession no.: B03075172C); Lim, T.J. (1948, November 28). War on diphtheria hots up. The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Diphtheria: Govt’s new measures. (1962, March 31). The Straits Times, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

National Centre for Infectious Diseases. (n.d.). Diphtheria. Retrieved from National Centre for Infectious Diseases website. ↩

-

Seow, B.Y., & Lim, M.Z. (2017, August 6). Foreign worker dies in first local diphtheria case in 25 years. The Straits Times, pp. 2–3; Choo, F. (2017, August 11). No evidence diphtheria has spread further, says MOH. The Straits Times, p. 9. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ministry of Culture. (1971). Singapore 1971 (p. 196). Singapore: Ministry of Culture. (Call no.: RCLOS 959.57 SIN); Jabs for primary one pupils in 1971. (1970, July 7). The Straits Times, p. 4. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

For instance, in 1973, there were 600 hospital admissions and 11 deaths due to measles. In the case of rubella, the incidence rate was 8.5 per 100,000 deliveries at Kendang Kerbau Maternity Hospital during the period November 1969 to December 1971, with many developing complications and the more serious cases resulting in mental retardation. See Goh, K.T. (1985, June). The national childhood immunisation programmes in Singapore. Singapore Medical Journal, 26 (3), 225–242, p. 231. Retrieved from Singapore Medical Association website. ↩

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Measles. Retrieved from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website; National Centre for Infectious Diseases. (n.d.) Measles. Retrieved from National Centre for Infectious Diseases website. ↩

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Rubella. Retrieved from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website; National Centre for Infectious Diseases. (n.d.). Rubella. Retrieved from National Centre for Infectious Diseases website. ↩

-

Clinging to measle belief is rash act. (1980, April 17). New Nation, p. 5. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Measles vaccination a must. (1985, July 27). The Straits Times, p. 12; A three-in-one vaccine for infants. (1989, October 27). The Straits Times, p. 28. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Oon, C.J. (1979, November 7). Towards a cure for liver cancer. The Straits Times, p. 6. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Baruch Blumberg: Facts. (n.d.). Retrieved from Nobel Prize Organisation website; Liver cancer virus can be curbed. (1979, September 28). New Nation, p. 5; Vaccine for cancer? (1980, September 29). New Nation, p. 11. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Hepatitis – the ‘silent killer’. (1984, September 10). Singapore Monitor, p. 13; Chua, I. (1985, May 29). The fight against hepatitis. The Straits Times, p. 3; Ngoo, I. (1979, October 21). S’pore is worst in the world. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

An all-out war on hepatitis B. (1983, August 3). The Straits Times, p. 1; Lim, J. (1983, August 3). Plan for mass immunisation against hepatitis B. The Business Times, p. 1; Wong, K.L. (1985, October 29). No mass vaccination against hepatitis B. The Straits Times, p. 18. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Kong, S.C. (1987, August 2). Low-cost anti-hepatitis B jabs for newborns. The Straits Times, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG. ↩

-

Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts. (2000, October 21). Speech by Mr Chan Soo Sen, parliamentary secretary (Prime Minister’s Office & Ministry of Health), at the international hepatitis B awareness weekend opening ceremony on Saturday, 21 Oct 2000 at Great world city [Speech]. Retrieved from National Archives of Singapore website. ↩

-

Tan, K. (2001, November 8). Benefits of vaccine outweigh risks. The Straits Times, p. 18; Oon, C.J. (2009, November 7). Hepatitis vaccination: It began in Singapore. The Straits Times, p. 106; Oon, C.J., & Kwek, K. (2011). A cancer vaccine that transformed Singapore and the world: The battle against hepatitis B (pp. 8, 54). Singapore: Straits Times Press Reference. (Call no.: RSING 614.593623 OON); World Health Organization. (2001). Hepatitis B immunization: Introducing hepatitis B vaccine into national immunization services. Retrieved from World Health Organization IRIS website. ↩

-

Ministry of Health Singapore. (2021, July 17). Vaccination data. Retrieved from Ministry of Health website. ↩

-

Chew, H.M. (2021, May 31). People who want alternative Covid-19 vaccines can get them under special access route. CNA. Retrieved from CNA website. ↩

-

Kurohi, R. (2021, May 31). 6 key announcements from PM Lee Hsien Loong’s address on Covid-19 plans. The Straits Times. Retrieved from The Straits Times website. ↩