Strange Visions of Singapore and the Malay Peninsula

From a letter written by a human-monkey chimera to a dog who became king, Benjamin J.Q. Khoo regales us with four fantastical tales that reflect European views of Southeast Asia.

From the 16th to 18th centuries, European ships returned from their sojourns to distant lands carrying not only shipments of fine spices and finer haberdasheries but also descriptions of these faraway places. Some of these were published based on first-hand observations and are unparalleled in historical detail, while others are highly embellished accounts, infused with heightened sentiments of atypicality and danger. Mixed in with this basket are fictional accounts that occasionally mirror closely the narratives of real ones.

Many of these adventures proved to be endlessly entertaining and were remarkably popular. Indeed, the enduring appeal of these accounts lies in the fact that they provided readers with “the shoes of flight”, allowing them to dream of mobility in an age when travel was largely inaccessible and imagine societies vastly different from the ones they lived in.1

Unbeknownst to many, Singapore and the Malay Peninsula, situated as they were at the crossroads of an increasingly curious and interconnected world, also featured in these flights of fancy.

Whence Solomon’s Ships Return

For would-be explorers and adventurers of the sea, the Bible contains lines of tempting mystery. In the Book of Kings, it is written: “And King Solomon made a navy of ships in Eziongeber, which is beside Eloth, on the shore of the Red Sea, in the land of Edom. And Hiram sent in the navy his servants, shipmen that had knowledge of the sea, with the servants of Solomon. And they came to Ophir, and fetched from thence gold, four hundred and twenty talents, and brought it to King Solomon.”2 But gold was not all that Ophir produced; the ships of Solomon also brought back other commodities: silver, ivory, apes and peacocks, algum-wood and precious stones.3

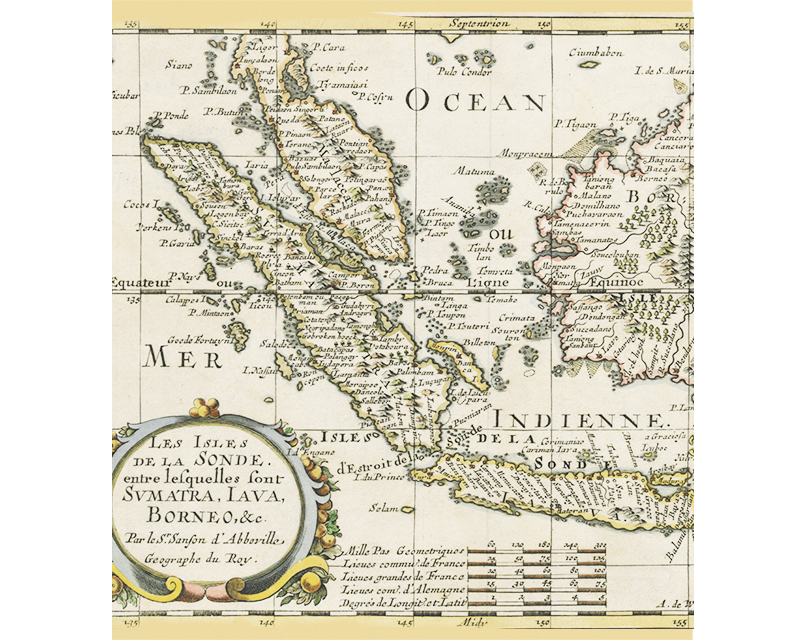

Where, then, is this Ophir? To date, there is no agreement. Suggested locations extend from Arabia, Peru, India and Ceylon to numerous places in Southeast Asia, including the Malay Peninsula (which Greek and Roman geographers of classical antiquity called the “Golden Chersonesus”, meaning the “Golden Peninsula”).

Given the speculation as to its location, it is not at all surprising to learn that Singapore was also touted as a possible site for the mystical Ophir. This suggestion was advanced by the Calabrian theologist, geographer and occasional demonologist, Giovanni Lorenzo d’Anania.

In his Universale Fabrica del Mondo, overo Cosmografia (Universal Fabric of the World, or Cosmography), d’Anania takes his reader on a veritable tour of the known 16th-century world. The first and second editions contain nothing extraordinary but it is the third edition, published in 1582, that includes certain interesting additions about Singapore.4

“But we return”, d’Anania writes, “close to the equinox, beyond the cape of Singapura, which overlooks the southern part of the continent, where many islands extending east are [located]”.5

Many of these places that d’Anania mentions make little sense to us today: there is Temian, Campar and the island of Poverera, and close by the shallows of Capaccia, the mouth of the river Dara, Capasiacar, with the little islet of Canados, then Ciagna and Saban and its Strait Calatigan, and after that, Andrapara and Manancavo, where great quantities of gold can be found.

However, after the roving eye is satisfied, presumably with the aid of a map, d’Anania directs the reader to “make a turn towards Singapura” where “quantities of ivory, aloe[wood] and all sorts of aromatics” can be found, the island “to which Solomon’s fleet navigates every year from the Red Sea”.6

Singapore’s tenuous connection to Solomon’s Ophir likely rests on the famed wealth of the island as a centre of trade and a collection point for the merchandise of the world, for which it was known in earlier times. As d’Anania, approximating knowledge from the Portuguese historian João de Barros, relates, Singapura was a “market” (mercato), where all the vessels of India and China sailed to. This entrepot was later abandoned for the traffic of Melaka.7

The Monkey’s Letter

If Ophir seems familiar, much less well-known are the fantasies of the French writer Nicolas-Edme Rétif. Rétif, who used the pen name Restif de la Bretonne, was the author of several salacious titles such as Le Paysan Perverti (The Perverted Peasant; 1775), Le Pornographe (The Pornographer; 1769) and L’Anti-Justine; ou, Les Delices de l’amour (The Anti-Justine; or, The Delights of Love; 1798). In all, Rétif produced over 200-odd works ranging from biographies to science fiction and short stories, covering topics that vary from politics to incest.

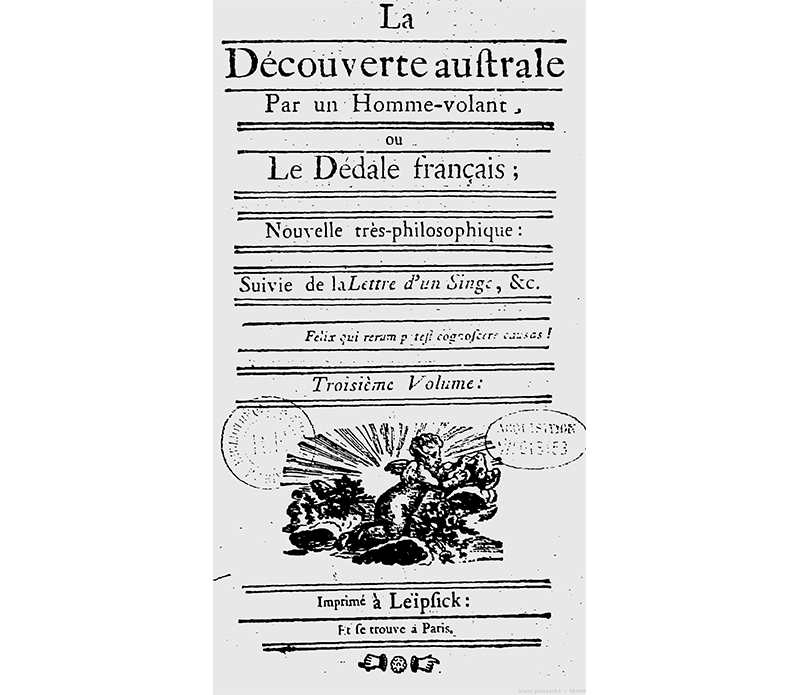

Among his moderately successful publications is one often acclaimed as a proto-work of science fiction, La Découverte Australe par un Homme-volant, ou le Dédale Francais (The Southern Discovery by a Flying Man, or the French Daedalus).8 Published in 1781 in four volumes, it is a novel of great eccentricity and social critique although its shock value has been very much blunted by the passage of time.

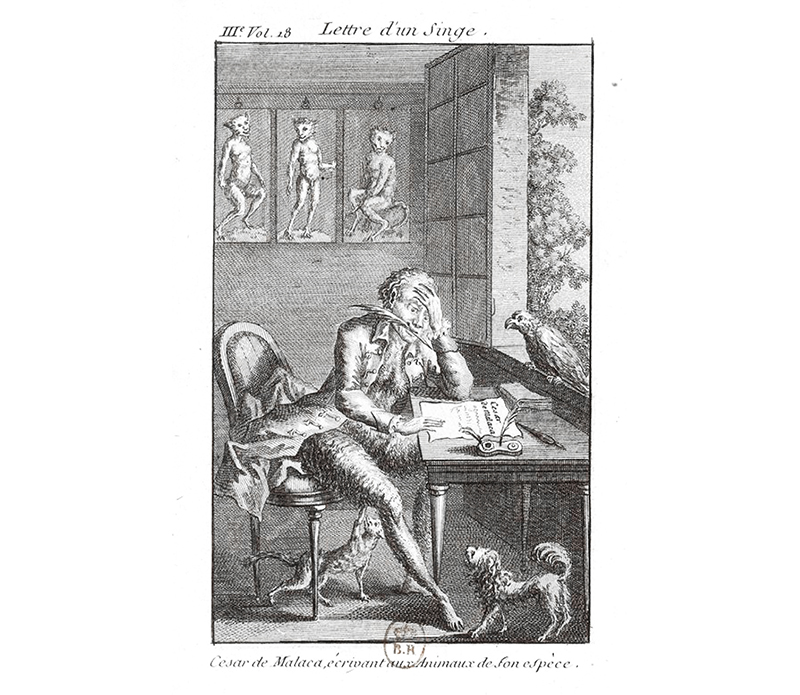

In the third volume is a transcript of a letter written by a fantastical half-monkey to his species. Titled Lettre d’un Singe (Letter by a Monkey), the epistle relates the extraordinary circumstances of his plight and plea.

This demi-simian was said to be born of a union between a woman of Melaka and a baboon. Considered an abomination, the chimera was destined to be drowned but a European trader who happened to be on the “Peninsula of Singapore” saved him. He was christened César and later given to an Australian at the Cape of Good Hope. From there, the creature was transferred to a certain Salocin-emdé-fitre (an anagram of Nicolas-Edme Rétif), who made him a present to a respectable dame thereafter.9 Now writing from Paris, where he had been brought up and educated in human ways, César of Melaka had cause to write a lengthy diatribe against the race of men to his apish brethren.

Man, the “king of the world (roi du monde)”, César rages, only thinks of inflicting misery, perpetuating fopperies, and consecrating barbarism in blasphemy of the laws of nature and religion. He espouses equality and fraternity but contradicts his own ideals.10 He is cruel and hypocritical, especially in enslaving his fellow men, and exhibits slavish pretence to religion. And as he builds up his arguments, César of Melaka twists his verbal knife – it is Man who is the true chimera, “engendered of a Tiger and a Hyena”, with his brutal lust for cruelty and violence.

To his simian brothers, César exhorts a singular warning – apes should not ape man, for he is a base ape. The dream of humanity is a mere nightmare. “Yes, fortunately I am a monkey,” he writes, “and not subject to human laws and prejudices!”11

Rétif’s monkey from the Peninsula or Strait of Singapore mixes natural and colonial history, scientific imagination and lively anecdotes into a trenchant social critique of his times that would not be out of place given his revolutionary milieu. However, if change was afoot, we would certainly be surprised if it concerned a royal pooch.

The Dog Who Became King

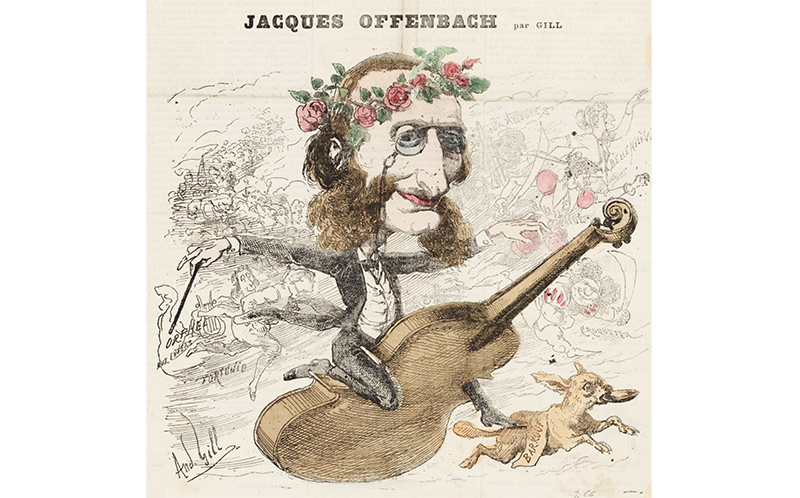

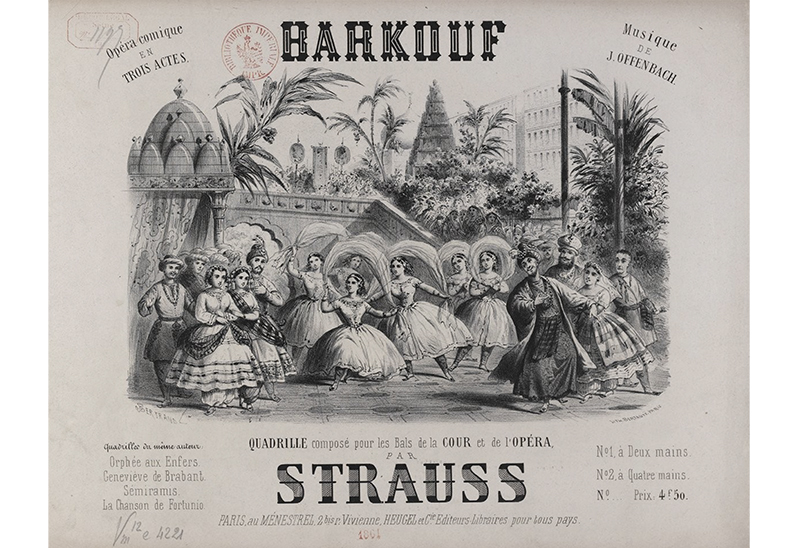

In 1860, the Parisian elites were witness to the ill-starred debut of Barkouf by Jacques Offenbach, a German-born French composer, cellist and impresario of the Romantic period. Over three acts, the audience was treated to courtly intrigues, forced marriages and foreign invasions within an entirely fictitious Mughal Empire, the comic genius of the piece being sustained by a dog, the titular character of the opera, who is appointed to the reins of governorship. Offenbach had exercised much creative licence; in fact, he had lifted much of his opera from a fable set in the Malay Peninsula. The original 1784 work, titled Mani et Barkouf, came from the pen of the Abbé François Blanchet, a French priest.

In the original tale, there was once a certain mandarin, the viceroy of Johor, who ruled his province with an iron fist. Injustice and cruelty led the people to rebel, defenestrate their tyrant and declare their independence. This uprising came to incur the wrath of King Chaou-Malon of Siam, who arrived with his army to subjugate Johor. Frightened at the king’s might, the Johorese quickly surrendered and submitted in tears, and their chiefs were brought before the Siamese king on the back of elephants.

“Base vermins [in other versions, vile insects] who have dared to offend the King of the White Elephant,” the king thundered, “you do not deserve to be governed by one of my mandarins”. He then summoned his dog Barkouf and placed it on the throne of Johor. Turning then to a Chinese man named Mani, who had long been established in Johor, he appointed him as prime minister and directed him to manage the affairs of the king.

After the Siamese king departed, both mutt and man got on extremely well. Each played his role to perfection; the dog Barkouf strutted in pageantry and presided over his royal councils, while the minister Mani reformed the laws and enhanced the prosperity of the state.

The province of Johor was well governed until an army of barbarians from the “Peninsula of Melaka” attacked. Barkouf and Mani rallied the troops and together they drove out the intruders, winning a great victory. But alas! Barkouf the sultan was wounded in battle and died from a poisoned dart. Mani then led a deputation to report this sorry news to the king of Siam.

Pleading for a successor, Mani cried, “deign therefore to order that we always be under the rule of a mastiff!” Upon hearing this, King Chaou-Malon grew pensive. “If the people bestow too much regard to their quadrupeds as chiefs,” he mused, “they might grow restless and rebel against the rule of my mandarins. Why, even my own royal crown might be endangered by a dog!”

Ruminating thus, the king decreed that his mandarin, Miracha, should take charge of the province of Johor instead. Needless to say, the people lived unhappily ever after as the king’s minister was incomparable to the ruler-dog. Blanchet’s moral is this: “the next best to an efficient emperor is an indifferent prince who delegates to an able minister.”12

Monarch haters, dog lovers and the general cognoscenti were tickled pink by this entirely fictitious fable of the dog-king of Johor. The story was reprinted in many fashionable magazines of the day, such as The Universal Magazine of Knowledge of Pleasure, The Edinburgh Magazine, The Lady’s Magazine, and even in La Feuille Villageoise (The Village Paper). Such was the story’s prominence that it was also rendered into poetry in French and English, and later, as we know, turned into an opera. Blanchet’s story was immensely creative and entertaining. But we save the fullest and most imaginative tale for the last.

An Antipodean Arcadia

In 1718, a travelogue divided into four parts appeared in print with the title Relations de Divers Voyages Faits dans l’Afrique, dans l’Amerique, et aux Indes Occidentales (Relation of Several Voyages made to Africa, America, and the East Indies).13 This account concerns the life story of the French naval officer Dralsé de Grandpierre who, at 16, runs away from his father’s house in Rochefort, southwestern France, for Bueno Aires.14 From Argentina, we follow him on his various adventures, from his capture and imprisonment by the English to his travels into parts of Africa. Later, he becomes involved in the slave trade and travels to places such as Martinique, Benin and Mexico.

Grandpierre was a keen observer of the places he visited and their inhabitants, and such is the value of his work that historians have referenced it in their research. There is, however, one small problem: his voyages were all imaginary. Besides the entirely fictitious nature of some of his travels, no other external verifications of Dralsé de Grandpierre himself seem to exist. But before we dismiss this fiction out of hand, his work contains a story within a story, describing a marvellous island newly discovered in the Straits of Singapore, bearing a name many might find familiar.

The story of Grandpierre’s voyage and discovery of this wonderful and mysterious island begins with a description of his position in the straits between Johor and Sumatra. “As we advanced through this Strait,” Grandpierre relates, “we find there such a great quantity of islands that we know not the number of.”15

Later, Grandpierre’s vessel narrowly escaped shipwreck and dropped anchor in the straits for a few days. It was then that Grandpierre and his crew noticed a small prow sailing towards them, carrying a woman, three men and a young child. Two distinguished-looking young men boarded Grandpierre’s ship, and were given food and lodging. They subsequently tell our protagonist their story.

The two young men turned out to be princes of Golconda (in Hyderabad). After the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb took the Kingdom of Golconda in 1687, as they related to Grandpierre, their grandmother, a member of the dispersed harem, escaped with her infant daughter. The daughter grew up, married a general and lived in luxury. However, after giving birth to two sons, her husband died while fighting a war. The family lost their wealth and were reduced to poverty. Beset by sudden destitution, their mother brought the two young boys to São Tomé de Mylapore (present-day Chennai) where she sought the protection of a rich Portuguese man. Although he took them in, he later brought the boys to Macau and left them there.

After reaching man’s estate, the two princes longed to see their mother again. So when the two young princes met a group of Chinese men headed to Batavia (present-day Jakarta), they decided to join them, hoping to then find a way back to India. However, after encountering a vicious tempest near the island of Pedra Branca (a small island about 24 nautical miles, or 44 km, to the east of Singapore), all lives were lost except for the two fortunate princes who ended up hopping from island to island in search of sustenance. After wandering about and barely surviving, they arrived at a fourth island where they stumbled upon a settlement.

It was then that the two princes discovered, to their great surprise, not only did the people speak the Malabar language (Lingua Malabar Tamul) but that the community was made up of other survivors from Malabar who were also shipwrecked on the same island. After they had explained their life story and how they came to be shipwrecked, the villagers decided to welcome them with open arms. The two princes were brought betel and tobacco, toured the settlement and were generally feted by all. And as they celebrated, recounting their story to every curious individual, one of the women suddenly fainted.

The following morning brought more drama. The woman who had collapsed the night before entered their chamber and asked the princes to continue with the rest of the story. When they had finished, she fell on them, saying, “Ah my children! My dear children! It’s you, I have the pleasure to see you both… the joy to be reunited! O heavens, is it possible?”16 Soon after, the story of this wonderful reunion spread throughout the whole settlement, bringing joy to all and sundry.

This island is no ordinary place, recounts Grandpierre to his readers. Here was a true picture of the “Age of Gold”. Friendship and harmony reigned, liberty of religion existed, egality subsisted, there was no lack of needs and joy flourished always. There were no judges, no lawyers, no executioners and no need of doctors even, since the air was the best in the world, and for over 20 years only 10 had died due to natural causes.

Their mother’s tale, how she ended up on the island and how they strove to build this perfect society, is perhaps a tale too long to be repeated here, but it suffices to know, as the princes said, “there is no one happier than he who lives on this island”.17 If there was one slight imperfection, which induced the princes to leave, it was that there was no priest, sacrament nor proper church – this their belief could not abide by.

Such was the tale the princes related to Grandpierre and they made him promise to tell no one lest the island should fall under the domination of the Dutch, who were the dominant foreign power in the region at the time. This island was named Isle de la Pierre Blanche (“pierre blanche” being French for “white stone”, which is also what “Pedra Branca”18 means in Portuguese), a Malabarese Arcadia, whose location was kept secret among the innumerable islands in the straits between Johor and Sumatra.

Setting the Imaginary Against the Real

These four entertaining vignettes that touch on Singapore and the Malay Peninsula represent a chronicle of encounters that Europeans had with the region. These fantasies draw upon real and historical information for narrative verisimilitude, revealing not only that knowledge of Singapore and the Malay Peninsula was available and circulated among the European reading public between the 16th and 18th centuries, but also that it was consciously and creatively put to use.

It is also easy to see how these stories closely reflect European intellectual concerns as we move through space and time. Whether it is a search for the biblical Ophir, meeting animals that criticise the prevailing social mores and cultural practices, or encountering utopian societies of idealised equality, what we glimpse are the contours of a distinctively European imagination, tied to the events and preoccupations of the period the tales were produced.19

Finally, we also have to be aware that these imaginative visions impinge upon the realities of the world they drew inspiration from. These stories work to assemble and reduce the complex realities of these very real places to the level of stereotypes. This can be gleaned from the last two narratives, where the region was used as a canvas for a utopia or a place where a dog can be king, an image of nonsensical despotism allowed free rein.

Fuelled by expanding geographical knowledge, the writers of these fantastical stories tried to make sense of change in the world, all the while changing how people made sense of the world.

Benjamin J.Q. Khoo is a research officer at ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute and a 2020/21 Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow. Studying the histories of the early modern world, his research is currently focused on networks of knowledge and diplomatic encounters in Asia.

Benjamin J.Q. Khoo is a research officer at ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute and a 2020/21 Lee Kong Chian Research Fellow. Studying the histories of the early modern world, his research is currently focused on networks of knowledge and diplomatic encounters in Asia.NOTES

-

Mary B. Campbell, The Witness and the Other World: Exotic European Travel Writing, 400–1600 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1998), 146. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

1 Kings 9:26–28. The Holy Bible (King James Version). ↩

-

Other mentions of Ophir in the Bible can be found in 1 Kings 10:12, 14; 1 Kings 10:21–23; 2 Chronicles 8:16. ↩

-

Giovanni Lorenzo d’Anania, L’universale Fabrica Del Mondo, overo Cosmografia Divisa in Quattro Trattati (Venezia: Presso il Muschio, 1582), 265, Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/ARes37419. ↩

-

D’Anania, L’universale Fabrica Del Mondo, overo Cosmografia Divisa in Quattro Trattati, 265. ↩

-

D’Anania, L’universale Fabrica Del Mondo, overo Cosmografia Divisa in Quattro Trattati, 268. ↩

-

D’Anania, L’universale Fabrica Del Mondo, overo Cosmografia Divisa in Quattro Trattati, 268–9. ↩

-

See Mark Poster, The Utopian Thought of Restif De La Bretonne (New York: New York University Press, 1971). (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Nicolas Edme Restif de La Bretonne, La Découverte Australe par un Homme-volant, ou le Dedale Francais, vol. 3 (Paris: Leipzig, 1781), 14, 20, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k1019190.texteImage. ↩

-

Restif de la Bretonne, La Découverte Australe par un Homme-volant, ou le Dedale Francais, 31–32, 34, 55, 81. ↩

-

Restif de la Bretonne, La Découverte Australe par un Homme-volant, ou le Dedale Francais, 82; See also Londa Schiebinger, Nature’s Body: Gender in the Making of Modern Science (New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2004), 109. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

François Blanchet, Apologues et Contes Orientaux, etc. par l’auteur des Variétés Morales et Amusantes (Paris: Chez Debure, 1784), 72, Google Books, https://books.google.com.sg/books?id=CpWoSyxBoQAC&pg=PR55&lpg=PR55&dq=IV. ↩

-

Dralsé de Grandpierre, Relation de Divers Voyages Faits dans l’Afrique, dans l’Amerique, et aux Indes Occidentales (Paris: Chez Jombert, 1718). (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RRARE 910.41 DRA; Accession no. B20025321D; Microfilm no. NL29328) ↩

-

De Grandpierre, Relation de Divers Voyages Faits dans l’Afrique, dans l’Amerique, et aux Indes Occidentales, 1–3. ↩

-

De Grandpierre, Relation de Divers Voyages Faits dans l’Afrique, dans l’Amerique, et aux Indes Occidentales, 297. ↩

-

De Grandpierre, Relation de Divers Voyages Faits dans l’Afrique, dans l’Amerique, et aux Indes Occidentales, 325. ↩

-

De Grandpierre, Relation de Divers Voyages Faits dans l’Afrique, dans l’Amerique, et aux Indes Occidentales, 348. ↩

-

Not to be confused with the earlier Pedra Branca mentioned in the essay. ↩

-

Paul Longley Arthur, Virtual Voyages: Travel Writing and the Antipodes, 1605–1837 (London: Anthem Press, 2011), 3. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩