Unravelling the Mystery of Ubin's German Girl Shrine

What is the truth behind the German girl shrine on Pulau Ubin? William L. Gibson investigates the history of Pulau Ubin to uncover the origin of the tale.

The German girl shrine, located on the southern coast of Pulau Ubin, has captured the popular imagination in a way that few other shrines in Singapore have. Apart from news stories, the shrine is the subject of documentaries, a play and a telemovie based on that play. It has even inspired a six-minute piece written for a Chinese orchestra.

According to local folklore, the shrine memorialises a German girl who is believed to have died on the island. At the outbreak of World War I, the girl was supposedly living with her parents on a coffee plantation on Ubin. When British soldiers came to capture her family, she bolted, only to stumble off a cliff to her death. After the war, her parents returned to look for their missing daughter, but due to communication difficulties, were unable to find any trace of her. Over time, a simple shrine was built at her gravesite and her spirit is worshipped to this day.

While fascinating, a close examination of the account reveals a number of major inconsistencies that make this story unlikely. Studying the history of the shrine shines a light on the practice of folk religion on Pulau Ubin and the Singapore-Johor region, and also demonstrates the power of the mass media to simultaneously generate, preserve and distort historical memory.

Chia Yeng Keng’s Account

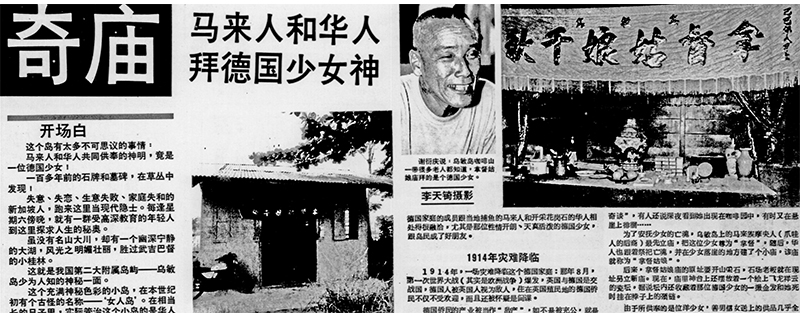

The best-known version of the German girl story today is largely the product of a Teochew man named Chia Yeng Keng (谢衍庆), born in 1928 and a resident of Ubin since 1931 (he died in the mid-2000s). Chia lived near the shrine and claimed to be an authority on it: between 1987 and 2004, he gave no fewer than seven separate interviews that appeared in English and Chinese newspapers, was featured in a documentary film and even gave an oral history interview deposited with the National Archives of Singapore.1

In his first print interview in 1987, Chia told the 新明日报 (Xin Ming Ri Bao; Shin Min Daily News) newspaper that the girl was of Dutch-German ancestry. Her parents were from Holland and the family lived on a coffee plantation on the western side of the island. However, Holland was neutral during World War I and the British did not intern Dutch citizens. In subsequent interviews, Chia dropped the Dutch ancestry and merely said that the family was German.

Later, Chia freely admitted that he had no way of knowing if any part of the story was true. When pressed for details in an oral history interview in 2004, he protested: “I was born more than 10 years after the death of the German girl so I don’t know anything about her.”

According to Chia, the story had been related to him by a village elder he addressed as Uncle Foon Da, a man from China who had lived on Ubin since the 1880s. Uncle Foon Da, however, was not an eyewitness to the events himself. He told young Chia that he did not personally see the body of the girl but had only been told of the story by others.

So, how much of the German girl story holds up to scrutiny? And what can it tell us about the history of Pulau Ubin?

Of Coffee Plantations and Mysterious Germans

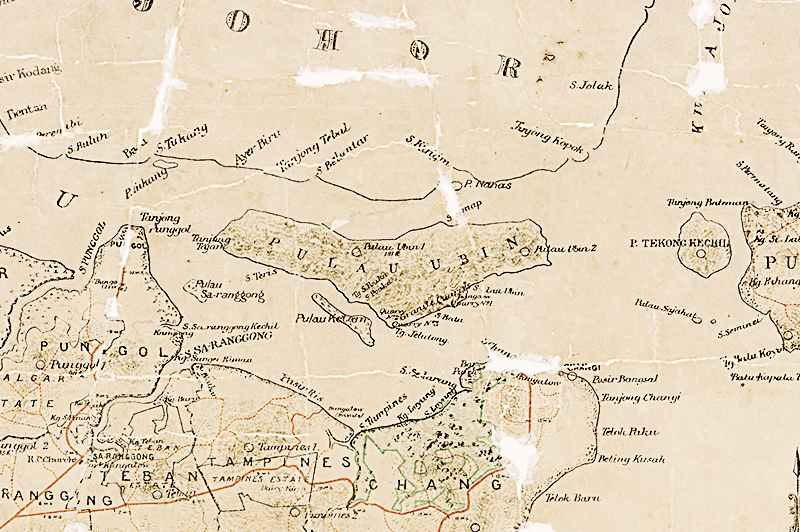

There was indeed, at one point, a coffee estate on Pulau Ubin. It was opened in 1880 by Thomas Heslop Hill, a British planter who grew both coffee and cacao on 150 acres (around 61 hectares) of land.2 Pulo Obin Estate, as he called it, was located on the western end of the island, exactly where Chia said the German coffee plantation had been located.

D. Brandt and Co. was the trading agency that represented the estate and owned an interest in it as well. The company had been founded in 1878 by Germans Daniel Brandt and Herman Muhlinghaus.3 These names were uncovered in the early 2000s and subsequently presented as proof that there were Germans living on Ubin at the beginning of World War I. The records, however, tell a different story.

According to land registry documents, Brandt purchased the land from Hill in 1892 for $13,333.33, but sold it in 1907.4 The local coffee industry was in freefall by that time. The coffee leaf rust disease caused by the virus Hemileia vastatrix spread to Malaya around the turn of the 20th century and promptly decimated plantations already fighting a boom in Brazilian coffee that was depressing the global market. Across the region, coffee was replaced with cash crops like rubber. In 1910, the Pulau Ubin coffee estate was bought by the British-owned Serangoon Rubber Company, which replaced the coffee plants with rubber trees.5

In 1914, when the war broke out, The Singapore and Straits Directory listed the Pulau Ubin estate as the only plantation remaining on the island, occupying 789 acres with 352 acres of rubber and coconut under cultivation. The estate manager was F.W. Riley, an Anglo-Irishmen, and no women were recorded as living on Ubin in the “Ladies Directory” in that year.6

In a nutshell, there was no coffee plantation in operation on Pulau Ubin in 1914 and no evidence to suggest a German family had been living there at the time. However, based on what we know about how the British authorities treated Germans in Singapore in 1914, we can speculate what their fate might have been, had they existed.

After war was declared on 14 August 1914, all German and Austrian nationals in the Straits Settlements were required to swear not to undertake “hostile acts against Great Britain”. The British were initially hesitant to intern German families who had been living in Singapore for decades and were pillars of the business and social world, but after Germany began to intern enemy subjects, the British decided to respond in kind.7

On 23 October 1914, all German and Austrian males in Singapore were ordered to report at the P&O Wharf at New Harbour (now Keppel Harbour) the following afternoon at 2 pm, to be taken to the quarantine facilities on St John’s Island. Married men were allowed to return to mainland Singapore on 25 October for “a few hours”. Within the week, they were transferred to the army barracks at Tanglin, which had hastily been converted into a prisoner camp – over 200 men were held there. By 28 October, it was announced that German women and children would also be removed from Singapore and allowed to relocate to “any place not within ten miles of the sea or a navigable river” within the Federated Malay States or to a neutral country.8

These facts considerably complicate the German girl narrative. First, there was no raid leading to the girl’s untimely death. Second, the girl’s mother (or perhaps amah, or nanny, if there had been no mother) would have stayed with her when her father left, and her father would have returned home the following day, at least for a few hours. If the girl had indeed gone missing, the alarm would have been raised immediately. Yet there is no trace of reports of a missing European girl in the newspapers of the time.

Finally, there is no satisfactory explanation as to why the German girl’s family was unable to find her when the war ended four years later. Chia suggested that communication difficulties presented an insurmountable barrier, but this seems unlikely given that the family would have had access to interpreters. The story of a family showing up to look for their missing daughter on Pulau Ubin is a sensational one that would surely have made it into the press, yet no such story appeared in the newspapers of the day.

Despite a careful search of the archives, there is no historical evidence to substantiate the German girl story. This leads us to the question: whose shrine is worshipped on Pulau Ubin today?

The Keramat of Pulau Ubin

Intriguingly, the first newspaper article to describe the German girl shrine makes no mention of Germans at all.

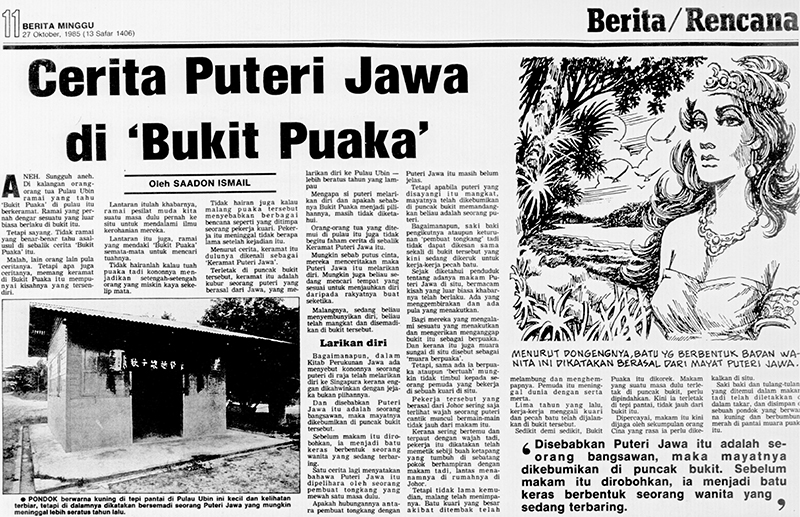

In 1985, an article in the Malay newspaper Berita Minggu mentioned the grave of a princess from Java that was located on a hill on the island. She had “fled to Pulau Ubin over one hundred years ago”, perhaps because of a broken heart or to avoid an arranged marriage. In another version, she was “cared for” by a wealthy tongkang (bumboat or lighter) builder. When she died, her body “became a hard rock shaped like a woman lying down”. She was said to later haunt the hill as a hantu puteri, or ghost princess, seducing a quarry worker from Johor who met a terrible fate.9

The writer, Saadon Ismail, explained that quarrying work on the hill required the grave be removed and a shrine was then built by the seashore nearby, guarded by “a group of Chinese who feel it needs to be maintained”.10 The article concludes with the earliest known photograph of the shrine. The writer, however, cited no source for his information.

A guidebook published in 2007 noted that there was a datuk keramat on Ubin where a “holy woman” had been buried. “The back of the shrine has an oracle ‘eye’,” noted the guidebook, “which legend says will blink at votaries, promising to grant their wishes”.11 (In Malay, datuk is a term of respect. Among other things, it is used as a title for a person in a high position. A datuk keramat refers to a shrine that is worshipped and associated with earth, tree or rock spirits, though it could also be the spirit of someone who has departed.)

Often, the sites where these datuk spirits reside are worshipped by Malays as a keramat. Chinese migrants, familiar with earth spirits, adapted such keramat to their own traditions, progressively Sinicising them over time. Known as datuk kong, such shrines still appear by roadsides across Singapore. When quarrying was a major industry in Singapore, datuk kong shrines were often found nearby, so workers could ask for protection in the hazardous conditions, and one remains on Ubin, close to the German girl shrine.

The German girl shrine, too, once stood near a quarrying operation. According to Chia, the shrine was originally located on Ong Lye Sua, once a 190-foot-high (57.9 m) granite hill that has since been completely removed. It is now the deep pond of Ketam Quarry.12

In another account by Ahmad bin Kassim, who has lived on the island since the early 1940s, the grave belonged to an Indian Muslim craftsman from Johor who travelled to Ubin to work at the quarry. He died there and was buried on the granite hill – a story that lacks as much historical evidence as the German girl tale (for the record, Pak Ahmad had been told that the German girl fell off a cliff into the sea and had no grave).13

In an email to the author in March 2021, Pak Ahmad said that the keramat was a mound of dirt shaped like a mayat, a corpse. He was told the mound was once covered by a copper sheet and had batu nisan, or grave markers, but these had since been stolen. What was left was kelambu kuning, a yellow netting traditionally used to denote graves as makam, or sacred. Pak Ahmad also recalled that there were 99 steps to reach it, a significant number in Islamic architecture as there are 99 holy names for Allah.

The assistant caretaker of the shrine, Ah Cheng, recalled that the shrine was accessed by a flight of steep and narrow stairs. At the top, he remembered an “unusually curved rock formation that embraced what remained of the German girl in its alcove, sheltering her from the elements with the help of a simple mosquito net, draped over her grave”.14

Madam Tan, a resident of Pulau Ubin born around 1938, recalled red brick steps leading to the shrine. She said that Chinese, Indians and Malays all worshipped there and so as to not offend the Muslim worshippers, no pork was offered, only chicken and fruits. She did not know who was buried there, only that her mother would take her up the hill to worship on the first and 15th day of each lunar month.15 Ah Teck, a longtime taxi driver on the island, was told that 108 steps led to the shrine, the number being significant in Taoist-Buddhist cosmology.16

Chia also said that the shrine had become popular with gamblers by the time he was visiting it as a boy in the 1930s. Nearly a century later, this practice has not diminished as the shrine is still regularly visited by punters seeking luck in the 4D lottery (where people place a wager on a four-digit number that is matched against winning numbers).

Ants and Termites

If the shrine had indeed been built over a grave, who could have been buried there? The following accounts offer some clues.

In 1990, Chia told the Lianhe Wanbao newspaper that when plantation workers found the German girl’s body, she looked like a dead ant.17 In a subsequent 1993 magazine article, he said the body was “covered with ants” so the workers “threw soil over the remains”.18 Ah Cheng the assistant caretaker related in a 2017 interview that when the girl was discovered, she was “covered by a lot of ants and mud and was in a human body shape”.19

In another version of the story related by Ong Siew Fong, another long-term resident on the island and caretaker of the Wei Tuo Fa Gong Temple, the girl did not fall to her death but hid in a cave or outcrop at the top of the hill. When the villagers went to look for her, they discovered that “termites had made a tomb for her” and decided not to disturb the mound, a point that Chia also made in a 2003 interview.20 (Termites are known as white ants in Chinese.)

In this region, it is not uncommon for termite mounds to become the site of datuk keramat, with devotees worshipping the spirit in the mound after having good luck with lottery numbers. It is believed that the mounds of red and black ants bring bad luck, while those with white ants, or termites, bring good luck. These colours also correspond to the datuk spirits who reside in the mounds.21

This last point offers a possible origin for the German girl in the termite mound on the hill. The white datuk spirit of this shrine, gendered female due to the shape of the mound, became a “white” girl, her backstory embellished as a means of explaining how she came to rest in the ground on Ubin.

What can be said with certainty is that when the mound was subsequently excavated, no skeleton of a teenage girl or otherwise was found.

Quarries and Urns

In the 1920s, the Ong Lye Sua granite hill was bought by entrepreneur Wee Cheng Soon, who established quarrying works there. After Wee died in the late 1940s, the land was sold to the New Asia Granite Company; two decades later, it was acquired by Aik Hwa Granite.

Aerial photographs show that Ong Lye Sua was almost completely levelled by 1969. Within a few years, Aik Hwa would remove the land on which the shrine was located and agree to move it to a new home. Unfortunately, there is no record of this event in Aik Hwa’s company archives. While the exact date is not known, Chia suggested 1974, which seems plausible.

Aik Hwa built a clapboard hut near the sea and painted it yellow – the traditional colour of datuk kong shrines, reflecting their Malay roots – and hired a Taoist priest to conduct rites. Ong Siew Fong recalled that it was this priest who labelled the spirit as a “datuk maiden” (拿督姑娘) to denote its female gender.

He also named it Yatikakak. Yati, a Malay name with Sanskrit roots, is also one of the holy names of the Hindu goddess Durga, the protective mother, while kakak, which means “elder sister” in Malay, is an honorific for older women.

Aik Hwa also hired workers to exhume the mound of the original shrine. In the 1987 新明日报 (Xin Ming Ri Bao) article, Chia said they found a metal cross and some coins. However, in his 2004 oral history interview, Chia said the man employed to dig up the grave “refused to say anything”, that he “talked nonsense” and did not “believe in facts”. When the mound was opened, a “shape of a person” could still be seen, but aside from a few strands of hair, nothing else was found. Her bones, he repeated three times, had “become ash”.

Chin Tiong Hock, nicknamed “Bala”, had helped with the exhumation. His wife, Ong Siew Fong, recalled that the men found some “finger bones”,22 although these could possibly have been chicken bones from prior offerings. They also found a one-cent coin from British North Borneo dated 1890.23

The hair, cross and other coins were placed in an urn on the altar of the new shrine – or maybe not. In one interview, Chia claimed that the cross was taken by the men Aik Hwa Granite had hired to dig the grave. In 1990, Chia peered inside the urn “to verify that the hair and iron cross were there”, and he was shocked to find it empty. He later offered an implausible tale that the original urn had in fact been stolen and replaced with an exact replica, a story that has now become a part of the German girl lore.

Likely, though, the urn – a symbolic vessel to hold the datuk spirit – was probably always empty. A study of temporary shrines that have displaced older datuk keramat on construction sites in Malaysia points out that empty “Chinese-style urns, believed to embody the keramat spirit”, are commonly placed on the altar by Chinese companies that own the construction sites.24

In the late 1980s, Pulau Ubin underwent a transformation as quarrying operations wound down and thousands of workers departed. Within a decade, only a few hundred villagers would remain; by the late 1990s, the little German girl shrine was nearly forgotten. It was not mentioned in a 1998 survey of recreational use of the island that included religious and historical sites.25 A visitor in 1998 found it sorely neglected.26 The old caretaker had passed away and no one was looking after the shrine.

That situation was about to change dramatically.

Haunted Barbie

In 2000, the story of the German girl appeared in the coffee-table book Pulau Ubin: Ours to Treasure, written by nature enthusiast Chua Ee Kiam.27 The tale prompted film student Ho Choon Hiong to shoot a 17-minute documentary about the shrine (prominently featuring Chia). The documentary was shown at the 2001 Singapore International Film Festival, inspiring dramatist Lim Jen Erh to write Moving Gods, a play staged by The Theatre Practice in 2003. Ho directed and produced the play as a telemovie of the same name, which was broadcast on television in 2004.

The shrine was also featured in an episode of the Site and Sound documentary television series in 2004, hosted by anthropologist and architectural historian Julian Davison.28 The following year, it was discussed in Jonathan Lim’s Between Gods and Ghosts (2005), a book about Singaporean folklore.29

In his 2006 book, Final Notes from a Great Island, popular author Neil Humphreys wrote about a red and yellow sign in English, German and Chinese on Ubin that pointed to the direction of the “German Girl shrine”. Humphreys had taken the information of the shrine from a 2003 Straits Times article he found tacked to the wall of the shrine. (The story was written by ethnomusicologist Tan Shzr Ee, who had composed the soundtrack for the Moving Gods telemovie).30

Not long after, it was reported that an unnamed Ubin islander had a strange dream three nights in a row. A foreign girl had shown him the way to a Barbie doll in a store and asked him to bring it to the “Datuk’s Girl’s Temple” on Ubin. Sceptically, the man followed the instructions and was surprised to find a Barbie doll that matched the doll in his dream exactly.31 The doll was placed on the altar beside the urn, perfectly, if coincidentally, timed with the rise of social media.

This “haunted Barbie” of Pulau Ubin proved digital catnip to journalists, bloggers and ghost chasers. Following the cut-and-paste logic of online content creation, very few bothered to do much fact checking; through sheer repetition, the story recounted by the long-dead Uncle Foon Da to Chia in the 1930s had become the official version of the German girl tale.

The Sinicisation of the original datuk keramat would soon be cemented in the structure itself. In 2015, a down-on-his-luck Singaporean businessman travelled to the Goh Hong Cheng Sern Temple in Batu Pahat, Johor, where monks told him to build a shrine for the deity on Ubin.32 The wooden shrine was demolished and a slightly larger brick structure with granite cladding, a tiled roof and ceramic bamboo window bars was erected in its place.

A wooden sign above the entrance to the shrine has the words Berlin Heiligtum engraved on it, meaning “Berlin Sanctuary” in German, beneath the date 1896, a year mistaken for the commencement of World War I. A three-foot-tall (around 90 cm) statue of the German girl now sits on the altar beside the urn and the Barbie doll, a beatific smile on her face and a sprig of coffee berries grasped in her hand.

Popular fascination with the German girl story shows no signs of abating. In 2018, Singaporean composer Emily Koh wrote a piece for the Chinese orchestra titled “Fräulein Datuk”.33 More recently, in 2021, History Mysteries, a television show hosted by local actor Adrian Pang, featured an episode about the shrine.34

Punters seeking a fortune do not care if it is the spirit of a German girl or something else: so long as it brings good luck, they will continue to descend on Ubin and worship there.

As for myself, I first chanced upon the shrine in 2006 and continue to visit it frequently to this day. On a recent trip, I noticed a termite mound outside the wall directly behind the altar. Despite all the changes over the decades, perhaps the old datuk spirit still lingers around the place.

Dr William L. Gibson is an author and researcher based in Southeast Asia since 2005. Gibson’s book, Alfred Raquez and the French Experience of the Far East, 1898–1906 (2021), a biography of journalist, Alfred Raquez, is published by Routledge as part of its Studies in the Modern History of Asia series. His articles have appeared in Signal to Noise, PopMatters.com, The Mekong Review, Archipel, History and Anthropology, the Bulletin de l’École française d’Extrême-Orient and BiblioAsia, among others.

Dr William L. Gibson is an author and researcher based in Southeast Asia since 2005. Gibson’s book, Alfred Raquez and the French Experience of the Far East, 1898–1906 (2021), a biography of journalist, Alfred Raquez, is published by Routledge as part of its Studies in the Modern History of Asia series. His articles have appeared in Signal to Noise, PopMatters.com, The Mekong Review, Archipel, History and Anthropology, the Bulletin de l’École française d’Extrême-Orient and BiblioAsia, among others.

NOTES

-

“洋女变成‘拿督姑娘’供奉在乌敏岛小庙内当地人视为神灵” [“Foreign Girl Becomes a ‘Datuk Girl’”], 新明日报 [Xin Ming Ri Bao], 29 December 1987, 4; “奇庙” [“Strangely Wondrous Temple”], 联合晚报 [Lianhe Wanbao], 14 July 1990, 2. (From NewspaperSG); Samuel J. Burris, “The White Girl of Pulau Ubin,” Changi Magazine, November 1993, accessed 30 July 2021, http://habitatnews.nus.edu.sg/heritage/ubin/stories/2005/12/white-girl-of-pulau-ubin.html; Ho Choon Hiong, German Girl Shrine (film), 2000; Tan Shzr Ee, “Mystery Girl of Ubin,” Straits Times, 9 March 2003, 20; “90年前住在乌敏岛洋姑娘变拿督神” [“90 Years Ago a Foreign Girl Living on Ubin became a Datuk God”], 新明日报 [Xin Ming Ri Bao], 26 December 2003, 13. (From NewspaperSG); Chia Yeng Keng, oral history interview, 23 June 2004, transcript and MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 1 and 3 of 7. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. 002860) ↩

-

The Singapore and Straits Directory for 1881, Containing also Directories of Sarawak, Labuan, Siam, Johore and the Protected Native States of the Malay Peninsula and an Appendix (Singapore: Mission Press, 1881), 78. (From BooksSG; Call no. RRARE 382.09595 STR; Accession no. B03013713G; Microfilm no. NL1176) ↩

-

Hans Schweizer-Iten, One Hundred Years of the Swiss Club in Singapore, 1871–1971 (Singapore: Swiss Club, 1981), 396. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 367.95957 SCH) ↩

-

Crown lease 933. Singapore Land Authority (SLA) Deed Registry, volume 58 number 179 and Index to Land Book, volume 46 page 404. ↩

-

“New Companies,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 24 March 1910, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

The Singapore and Straits Directory (Singapore: Fraser and Neave, 1914), 787–88. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RRARE 382.09595 STR; Microfilm no. NL1185) ↩

-

Annual Reports of the Straits Settlements for 1914, (Slough, UK: Archive Editions, 1998) 646–47. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 959.51 STR) ↩

-

“German Prisoners,” Straits Times, 24 October 1914, 8; “Untitled,” Straits Times, 26 October 1914, 8; “Our Prisoners,” Straits Times, 27 October 1914, 5; “German Women and Children,” Straits Times, 28 October 1914, 8; “Local Prisoners of War,” Straits Times, 31 October 1914, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Saadon Ismail, “Cerita Puteri Jawa di ‘Bukit Puaka’,” Berita Minggu, 27 October 1985, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Saadon Ismail, “Cerita Puteri Jawa di ‘Bukit Puaka’.” ↩

-

Susan Tsang, Discover Singapore: The City’s History & Culture Redefined (Singapore: Marshall Cavendish, 2007), 106. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 959.57 TSA) ↩

-

This hill is sometimes called Kopi Sua (Coffee Hill). Kopi Sua was in fact located to the north, near Batu Kekek. See Seow Soon Hee, et al., eds., Ubin Our Heart and Soul (Singapore: Our Heart and Soul Commemorative Publication Editorial Committee, 2019), 30. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 959.57 PUL) ↩

-

Ahmad bin Kassim, email to author, 29 March 2021. ↩

-

Kenny Fong, Spooky Tales: True Cases of Paranormal Investigation in Singapore (Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions, 2008), 50. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 133.1095957 FON) ↩

-

Madam Tan, interview, Pulau Ubin, 5 April 2021. ↩

-

Ah Teck, interview, Pulau Ubin, 5 April, 2021. ↩

-

Burris, “The White Girl of Pulau Ubin.” ↩

-

Manisha Nayak, “A Powerful, Mysterious Singaporean Shrine Dedicated to a German Girl Who Died in WW1,” 23 February 2017, https://buzz.viddsee.com/how-did-german-diety-singapore-shirne. ↩

-

Ong Siew Fong, interview, Pulau Ubin, 5 April 2021; “90年前住在乌敏岛洋姑娘变拿督神” [“90 Years Ago a Foreign Girl Living on Ubin became a Datuk God”]. ↩

-

Cheu Hock Tong, “The Sinicization of Malay Keramats in Malaysia,” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 71, no. 2 (275) (1988): 45–47. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website). See also Lee Chow-Yang, “The Worship of Termite Mounds,” Isoptera Newsletter 9, no. 2 (1999): 3, http://www.chowyang.com/uploads/2/4/3/5/24359966/isoptera_newsletter_9_page_3_1999.pdf. ↩

-

Ong Siew Fong, interview. ↩

-

Chua Ee Kiam, Choo Mui Eng and Wong Tuan Wah, Footprints on an Island: Rediscovering Pulau Ubin (Singapore: Simply Green and National Parks Board, 2016), 55. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 333.78095957 CHU) ↩

-

Ban Lee Goh, “Spirit Cults and Construction Sites: Trans-Ethnic Popular Religion and Keramat Symbolism in Contemporary Malaysia,” in Engaging the Spirit World: Popular Beliefs and Practices in Modern Southeast Asia, ed. Kirsten W. Endres and Andrea Lauser (New York: Berghahn Books, 2011), 149. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSEA133.90959 ENG) ↩

-

Ng Koh Yee, “Recreational Land Use on Pulau Ubin” (bachelor’s thesis, National University of Singapore, 1998), https://scholarbank.nus.edu.sg/handle/10635/173038. ↩

-

“开发宝贵的旅游资源” [“Develop Valuable Tourism Resources”], 联合早报 [Lianhe Zaobao], 19 November 1998, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Chua Ee Kiam, Pulau Ubin: Ours to Treasure (Singapore: Simply Green, 2000). (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 333.78095957 CHU). Chua cites the 1993 article as his source. ↩

-

“The Last Wild Place to Change its Face,” In Site and Sound with Julian Davison. The Story of Singapore. Series 2, episode 12 (Singapore: Produced by the Moving Visuals Co. for the Media Development Authority of Singapore, 2004). (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RCLOS 959.57 SIT) ↩

-

Jonathan Lim, Between Gods and Ghosts (Singapore: Cavendish International, 2005). (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 133.1095957 LIM) ↩

-

Neil Humphreys, Final Notes from a Great Island: A Farewell Tour of Singapore (Singapore: Marshall Cavendish, 2006), 201–202. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 959.57 HUM) ↩

-

“乌敏岛姑娘庙竟拜芭比娃娃” [“Ubin Girl Temple Actually Worships Barbie Dolls”], 联合晚报 [Lianhe Wanbao], 18 June 2007, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Anonymous informant, interview, Pulau Ubin, 5 April 2021. ↩

-

Emily Koh, “Fräulein Datuk 拿督姑娘 (2018)”, accessed 4 August 2021, https://emilykoh.net/fraulein-datuk-拿督姑娘-2018/. ↩

-

“The German Girl Shrine,” History Mysteries S1, Ep 3, 2021, MeWatch, accessed 4 August 2021, https://www.mewatch.sg/watch/History-Mysteries-E3-The-German-Girl-Shrine-207218. ↩