In Their Own Words: The Early Years of The Substation

The development of the arts in Singapore is unimaginable without this arts centre dedicated to alternative voices. Key individuals from its early history tell Clarissa Oon how it got started.

A rundown former power station was transformed by artists and the government into an arts centre. And so began the almost inconceivable journey of Singapore’s first independent, multidisciplinary arts space – The Substation.

In 1985, the late influential drama doyen Kuo Pao Kun had a vision of an arts centre that would be accessible to all art forms, artists and cultures. The then Ministry of Community Development (MCD; now Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth) accepted his proposal and leased the building at 45 Armenian Street to Kuo’s Practice Performing Arts Centre Ltd (PPACL). The government also provided a $1.07-million grant towards the reconstruction and renovation of the building, which was completed in June 1990.

Opening in September 1990, The Substation predated the National Arts Council (NAC) and much of today’s state-planned arts infrastructure. In its heyday in the 1990s, particularly during Kuo’s tenure as artistic director from 1990 to 1995, it was the place to be in the arts. It was a space in which to experiment and make art and also engage in robust debate about one’s work, the arts and society. Singapore’s Ambassador-at-Large Tommy Koh was The Substation’s patron, and its board members during that period included former cabinet minister Ong Pang Boon.

“The Substation cannot begin to survive unless we start creating a new space within our inner selves – a space which is responsive to creative, pluralistic, artistic ventures,” wrote Kuo. Such ventures would, by nature, be “untried, raw, personal, unglamorous, slow in developing and often ‘not successful’, ‘not excellent’. There is no other way to nurture the young, innovative and experimental in art.”1

The art centre’s operating model was unique for a Singapore arts organisation at the time: ad hoc government grants coupled with the subleasing of some of its spaces to commercial enterprises such as a café. While financial sustainability was a challenge, it was home to hundreds of performances and exhibitions for more than 30 years.

The Substation moved out from Armenian Street on 30 July 2021 and has entered a new phase of its journey as an arts company.

In the three decades that it existed on Armenian Street, it had been an incubator of young artistic talent. Professor Tommy Koh noted in an op-ed in the Straits Times that the arts centre “has nurtured many recipients of the Cultural Medallion and Young Artist Award.” He said: “Eminent theatre practitioners, such as Wild Rice founding artistic director Ivan Heng, TNS [The Necessary Stage] artistic director Alvin Tan and TheatreWorks artistic director Ong Keng Sen were mentored by Pao Kun at The Substation.” The Substation also nurtured other lesser known artists as well, he added.2

Most critical of all were its values and culture. As Koh noted, “The Substation is about the freedom to innovate, to experiment, to challenge the establishment and conventional wisdom. It is about the process of art-making and less about its outcome.”3

At this point in the Substation’s history, it is now apt to revisit its beginnings. Key players of the time share their perspectives on the centre’s founding years.

The Arts Administrators

Securing the Building and Garden

In 1986, the power station on Armenian Street became the first property under NAC’s then new Arts Housing Scheme to receive a capital grant of $1.07 million for renovations;4 the scheme was administered by the MCD’s cultural affairs division, precursor of today’s NAC.

MCD allowed the former power station, earmarked for conservation, to be managed by a private, not-for-profit company on a 10-year lease. This was unheard of at the time: other buildings – shells of former schools converted into workspaces for arts groups – were leased out for only up to three years.

At the time, veteran arts administrators Juliana Lim and Tisa Ho were, respectively, deputy director and assistant director in MCD’s cultural affairs division. They share the decisions they undertook to let the arts centre fly, including allocating a garden behind the building to The Substation with permission from the Land Office.5 The garden became a key performance space before being sublet to a commercial tenant in the mid-2000s.6

(Right) Tisa Ho, former assistant director in the then Ministry of Community Development’s cultural affairs division. Courtesy of Tisa Ho.

Tisa Ho: Juliana had the idea that old buildings that were lying fallow could be better used, as the artists and arts groups that we knew were struggling for working space. The Telok Ayer Performing Arts Centre [TAPAC, now defunct] was, I think, the first experiment.

Juliana Lim: I went to take a look at The Substation. I remember climbing into the building, through this vertical ladder on the side of the building. I slid open this big, heavy door, entered this room, and found a floor with holes in it, and then the Land Office chaps came and said it was the generator room. This building was unlike the others, unlike TAPAC and all which used to be schools with many classrooms. The power station was not a building for co-sharing. In my subconscious mind, I thought, this is a building that has to go to one player because it’s quite a compact building, it was not big.

Ho: Structurally, it was obviously very sound, it was a very solid building. “Disused” doesn’t begin to describe the state that it was in; it was encrusted with bat and mouse droppings. But I thought the potential was exciting. There was one big space which could be used for a slightly different kind of performance space than the proscenium theatres and Drama Centre that we had then, and some potential workspaces upstairs.

Lim: We invited concepts from the bigger arts groups at the time. The reason why Pao Kun got the building was his proposal went way beyond an individual group’s need, unlike the rest who were looking for rehearsal space. It was multicultural, multidisciplinary – those were the words we liked.

This was a fresh concept, entirely his, and we were not going to co-own it, because we got no means to do this. We saw ourselves more as an enabler with PPACL as a tenant, than a co-owner.

For the capital grant [to cover the building’s renovations], we went to the Ministry of Finance, and I remember they were very lukewarm. And to be frank, I was very disheartened, and I think Tisa was the one who pushed it further.

Ho: I think we also made a case for preservation of our buildings, because there was a lot of talk about conserving the former Tao Nan School beside it [now The Peranakan Museum]. The climate was right, there was an awareness of urgency, of keeping your architectural heritage.

Lim: On the garden, I think what Pao Kun said was, “I want the link to nature.” There was a huge banyan tree. Basically, once we agreed with his vision of the building, we were very much swayed in his direction. The garden was Tao Nan School’s playing field, and I think the neighbour was also asking for it. The Land Office had to arbitrate, and they gave it to Pao Kun.

The General Manager

“Every day, I had to think, where to get money.”

In 1989, Tan Beng Luan left her civil service job to join PPACL. She knew Kuo from attending his directing course a few years before. Overseeing the founding of The Substation, she recounts the fundraising challenges of the early years – a Straits Times article in 1990 reported that the arts centre had to raise $700,000 for its first year’s operations.7

The Substation operated in this way: it rented out its spaces for artists to use at very affordable rates, and also initiated its own programmes. Dance Space, Word Space, Music Space and Raw Theatre were all programmes created by Pao Kun to spearhead or explore new possibilities in artmaking. We had a 120-seat black-box theatre, a garden, art gallery, dance studio, two classrooms, as well as a meeting room and office. There was also an art bookshop and café. MCD allowed us to sublet our spaces to commercial tenants. The ministry gave Pao Kun the freedom to set the artistic direction for the centre and we never had to seek approval for any of our programmes.

While the government’s capital grant paid for the building, the money for equipment and fittings had to be raised by PPACL. And it was really very hard. Every day, I remember one of my administrators would receive a call from the contractor to ask for payment. Once, we couldn’t even find $800 to pay for the air-con instalment.

But we did have supporters. Our first fundraising event was supported by many visual artists who donated paintings to The Substation that we sold. Our salaries were supported by the Practice Performing Arts School, an entity under PPACL which was financially stable and had a regular income through its classes. Up until Guinness [the beer company] approached us in 1991, it was very hard to get corporate sponsorship. This was before the establishment of the NAC, and when it came to sponsoring the arts, companies were very cautious.

One day we were having a meeting in the office. Suddenly the door opened, a gentleman and a lady walked in. They asked to speak to the manager. So I said, “Yes, what is your business?” They were from Guinness and wanted to find out more about The Substation. I took them to the café downstairs, answered all their questions, and then they expressed their interest in sponsoring.

Before Guinness, there was another company which wanted to support The Substation. But the condition was to have naming rights over the entire Substation. Of course, Pao Kun’s reaction was, no, The Substation [had] to maintain its name; we can name individual spaces within The Substation after a sponsor but not the entire building. When Guinness came in, they wanted to support The Substation with $1 million over five years, provided the theatre was named the Guinness Theatre. That was okay.

Up to that point, everything went quite well. But when we were about to close the deal, there was a request from Guinness’ UK office to say that in the agreement, The Substation had to guarantee that no performances or activities take place there that will damage the image of Guinness. Pao Kun said there’s no way The Substation can make this guarantee; we would have to work out a system to scrutinise all events in detail before we even let artists use the space, and it just wasn’t possible.

There was a lot of “ding-donging” [back-and-forth]. I often heard Pao Kun over the phone, trying to persuade the Guinness representative in Singapore so he could in turn persuade the UK office. Eventually Guinness counter-proposed to change the wording to something like: “The Substation has no intention of creating any damages to the image of the sponsor.” That finally was okay.

I remember asking Pao Kun – what if Guinness drops this whole sponsorship idea because you disagree with their original condition. You guess what his response was? He said, “Well, then we start all over again and look for another sponsor.” This ability to endure hardship and willingness to take a difficult journey is the character of Pao Kun.

I remember another incident. In early 1990, one of our board members, Mdm Li Lienfung [the late writer and vice-chairman of the Wah Chang group of manufacturing companies], called me. She had a friend who could be willing to occupy the gallery space for the entire year, which meant we could collect rental revenue. But I said the gallery cannot be rented out for a year because we won’t have the space for our [own] visual art activities.

So of course Mdm Li was very upset because she was really concerned about the financial situation of The Substation. But then, what to do? This issue about the strong artistic mission of The Substation – versus commercial usage and revenue collection – was a constant tension. You have to make a decision. For that same reason, it would never occur to Pao Kun to rent out the garden [as] it was the second biggest space after the theatre. I often say he led his team of board members through a difficult path full of ups and downs and hurdles. Fortunately, they were willing to come along [on the journey].

The Indie Musician

Building the Music Ecosystem, One Gig a Time

With the government’s ban on long hair and tightening of rules for live entertainment in the 1970s, the decade after that saw the entire local music scene in the doldrums. Original music in English by Singapore bands had largely disappeared from radio and TV, and the live music venues in those days were mainly hotel lounges.

Musician Joe Ng – frontman of 1990s indie band The Padres – talks about how things changed when indie music gigs began to be held at The Substation Garden.

In 1990, I was involved in writing for [pioneering indie music magazine] BigO. I was also starting to work in a record company and trying to organise gigs. It was quite challenging because the concept of original music was new for a lot of people. When I knocked on the doors of pubs and schools and said, “We’d like to have a local band play at your space, and they’ll be playing original music,” their reaction would be like “Hmm? Local music?”

When Pao Kun opened The Substation, me and [music producer] Nazir Husain went to meet him. We knew someone who facilitated the meeting. We said, “Hey look, can we also have music at The Substation Garden? The music will be what I’ll call left-wing music. There will be punk rock, there will be thrash metal, anything that is really non-mainstream, no Abba, no Richard Clayderman.” And Pao Kun was very cool about it and he said, “Oh sure.” Then I looked at him and I said, “Hey, it won’t be pretty music,” and then he said something like this: “The Substation is a place for people to experiment, a place for people to do anything they want.”

And true to his words, many years down the line, it wasn’t just non-mainstream music, you also had mainstream artists performing at The Substation. The genre, the categorisation of it for him, does not matter. What matters for him is that you have something to say, we have a space here, say it the way you want to say it.

The first gig that we organised, for the life of me I cannot remember who played, I cannot remember anything about it. But [Pao Kun] was there at the gig, and I think [he and] Professor Tommy Koh were sitting in the crowd in the garden, watching some thrash metal or heavy metal band.

I dare say that from 1990 to 1991, we must at least have had four or five gigs, and that was more than all the gigs featuring local music in the 1980s.

The impact The Substation made was incalculable. Teenagers would come for the gigs and say “Hey, why can’t we have this in my school?” At Ngee Ann Polytechnic, for example, they started their own series of concerts.

Every year, the number of gigs around town increased. In the late ’90s and early noughties, I remember looking at a newspaper or magazine listing and thinking, “Wah, so many gigs ah.” It was a domino effect where pundits started organising gigs themselves, and venues looking at this said, “Well, there’s a trend. There’s a market for Singapore indie music.” And [clubs like] Hard Rock Café, Sparks and Fire started to have indie music nights too.

The Theatre Maker

Learning and Receiving Criticism

The co-artistic director of established socially engaged theatre company Drama Box, Kok Heng Leun got his “baptism of fire” in the arts working as a programme executive at The Substation from 1992 to 1993. He credits the centre as a place of beginnings for many artists like himself.8

On one October evening in 1990, a group of young people – myself included – who had just graduated from the National University of Singapore, gathered at the garden of The Substation and decided to form Drama Box. We formed [the theatre company] because we wanted to do our own Chinese-language theatre, telling our stories. Drama Box’s first production, a double bill, was held at the Guinness Theatre in 1991.

Young practitioners like myself found The Substation a good place to start something new. Drama Box started without much connection with the bigger community; coming to The Substation made us feel like you were part of something bigger, part of a community.

For a new group, a beginning would require a supportive environment. The Guinness Theatre black box is small, with a manageable audience capacity. The flexible space in the theatre also allows directors to try things, to reconfigure, to start from “zero”. The floor plan of the black box indicated that the seats could be moved, and during the 1990s, it was such an exciting possibility.

Yet at the same time, we knew that once we started on something, we would subject our work to being critically examined by others. There were so many different practitioners of different backgrounds visiting and working at The Substation. Your work would be seen by these artists. You would even get to talk to them after the show at the café in The Substation. The Substation was the place where we knew we could be free, without being judged, but where we must learn how to receive critical opinions.

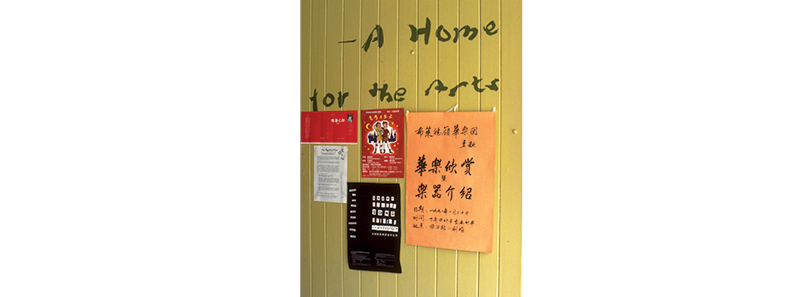

I remembered asking Pao Kun about the diversity of programming in The Substation. After a year, there were people who were quite confused about what the place was about. In fact, there were people who asked that The Substation should have a clearer identity for easy marketing purposes.

Pao Kun’s response was (and I paraphrase his words here): “The Substation is a home for the arts. So it should accommodate any kind of arts – traditional, contemporary, experimental and pop. So when people come to The Substation, they get to meet different artists, they get to meet different kinds of arts. Isn’t that good?”

Having a vision does not make a place tick. The values that the place embodies must be upheld by strong and firm leadership. All the artistic directors of The Substation are strong artists, visionary and also resilient. I have witnessed Pao Kun defending why certain artworks or performances were allowed to be showcased at The Substation gallery when queried by the public or even by the board of directors. By doing so, Pao Kun gave artists a sense of security that the place is one of freedom and openness.

The Board Member

“What is fringe today will become the centre of tomorrow”

Arun Mahizhnan, special research advisor at the Institute of Policy Studies, has had a long association with the arts. As Mobil Oil Singapore’s public affairs manager in the 1980s, he helped pave the way for the internationalisation and professionalisation of the Singapore Arts Festival through Mobil’s sponsorship of the festival, and was on the PPACL and then The Substation board for many years.

I was one of the pioneers in the arts domain in Singapore with management experience, but [who had] a very soft spot in our heart for the artist. I was not going to impose management on the artist, but I was going to impose management on the institution so the artists perform at their best.

Pao Kun was perhaps the greatest artist and arts leader Singapore has produced in modern times, but he was not a terrific manager. At the board level, I was one of those who brought that kind of experience. I think Pao Kun liked me because I could speak to him openly and frankly, which is saying more about him than me, in that he was able to accommodate such a diversity of perspectives, people who bring different talents to the table.

Funding was a challenge, but because it was Pao Kun, he could always bail us out; he just had to go and ask certain Chinese patrons, and they would give [him money].

More challenging was he was the father of the fringe theatre, the people who would not be recognised by established procedures. He was willing to give them space, both in a physical as well as creative sense. Every time a controversial issue like performance art emerged – it was a big controversy – he did give space for that. And he argued for it.9

Pao Kun’s contribution is in pushing the boundaries for what is allowed, which I think today, very few artists can do as well as he did. On the other hand, space is not as critical today because there are a number of other groups and platforms that have given space. When you talk about the 1990s, this wasn’t the case in Singapore. The Substation actually had a series called Raw Theatre. To think of it as a worthy cause, and to provide support for it in a systematic way, this is what Pao Kun basically institutionalised.

I think that the essence of The Substation is that we must always be at the fringe. Now, many board members and even some artistic directors disagree with this, but you see, what Pao Kun created was the fringe. It was not the centre, and I felt in whatever The Substation does in the arts, we must be very mindful of pushing the boundaries, extending and nurturing the fringe.

And what is fringe today will become the centre of tomorrow, you know, and then my point is we have to move on to the fringe. This was actually one of the big problems at The Substation’s board level. Whenever we were reaching the boundaries, some board members were very uncomfortable. At some point, Pao Kun felt very frustrated that the board was not unanimously supporting him. But I felt that the risk is worth taking. And Singapore is the better for it, The Substation is the better for it. I still feel that should be the role of The Substation.

Clarissa Oon is an arts writer and former journalist who heads Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay’s digital content and archives. She is working on a year-long series, PopLore, which celebrates and documents Singapore popular music and includes an exhibition on live music venues.

Clarissa Oon is an arts writer and former journalist who heads Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay’s digital content and archives. She is working on a year-long series, PopLore, which celebrates and documents Singapore popular music and includes an exhibition on live music venues.NOTES

-

Audrey Wong, ed., 25 Years of The Substation: Reflections on Singapore’s First Independent Art Centre (Singapore: The Substation and Ethos Books, 2015), 12. (From National Library Singapore, Call no. RSING 700.95957 TWE) ↩

-

Tommy Koh, “Fare Thee Well: The Substation’s Legacy Will Endure”. Straits Times, 6 March 2021, https://www.straitstimes.com/opinion/fare-thee-well-the-substations-legacy-will-endure. ↩

-

Koh, “Fare Thee Well: The Substation’s Legacy Will Endure.” ↩

-

Clarissa Oon, Theatre Life!; A History of Singapore English-language Theatre in Singapore Through The Straits Times (1958–2000) (Singapore: Singapore Press Holdings, 2001), 147. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 792.095957 OON). See also Juliana Lim, “Arts Housing Scheme – $10 a Classroom a Month,” Singapore Arts Manager 1980s/90s: Memories and Musings, 24 May 2009, https://julianalim.wordpress.com/2009/05/24/arts-housing-scheme-10-a-classroom-a-month/. ↩

-

Juliana Lim, “Substation Stories,” Singapore Arts Manager 1980s/90s: Memories and Musings, 15 December 2009, https://julianalim.wordpress.com/2009/12/15/substation-stories/. ↩

-

Lee Weng Choy, “The Substation: Artistic Practice and Cultural Policy,” in The State and the Arts in Singapore: Policies and Institutions, ed. Terence Chong (New Jersey: World Scientific, 2019), 204, 210. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 700.959570904 STA) ↩

-

“The Substation Plans Host of Activities to Raise Funds,” Straits Times, 16 May 1990, 26. (From NewspaperSG). ↩

-

Kok Heng Leun, “The Place of The Substation: A Space and a Place for a Beginning,” in 25 Years of The Substation: Reflections on Singapore’s First Independent Art Centre, ed. Audrey Wong (Singapore: The Substation and Ethos Books, 2015), 38–45. (From National Library Singapore, Call no. RSING 700.95957 TWE) ↩

-

Performance art was not funded by the government for 10 years starting from 1994. ↩