Siti Radhiah’s Cookbooks for the Modern Malay Woman

A number of cookbooks written in the 1940s and 1950s helped expand the traditional Malay culinary repertoire, as Toffa Abdul Wahed tells us.

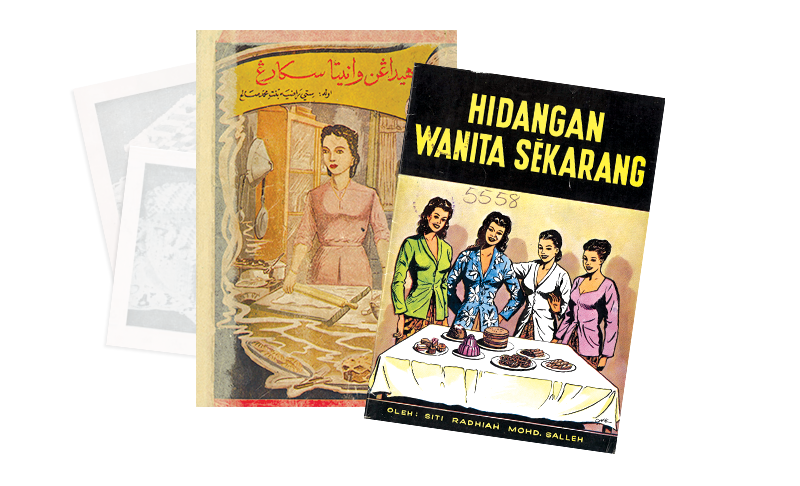

(Right) In 1961, Siti Radhiah’s second cookbook, Hidangan Wanita Sekarang, was published in romanised Malay. Image reproduced from Siti Radhiah Mohamed Saleh, Hidangan Wanita Sekarang (Singapore: Royal Press, 1961). (From National Library, Singapore, via PublicationSG).

The name Siti Radhiah Mohamed Saleh may not ring a bell to many, but she was one of the few female Malay cookbook authors whose works were produced and published in Singapore in the period between the end of World War II and independence in 1965.1 All in all, she wrote four cookbooks: Hidangan Melayu (Malay Dishes; 1948), Hidangan Wanita Sekarang (Dishes for Today’s Women; first printed in Jawi script in 1949 and reprinted three more times in Jawi before it was published in romanised Malay in 1961), Memilih Selera (Choosing Tastes; 1953) and Hidangan Kuih Moden (Modern Kuih Dishes; 1957).2

These publications not only reflect Siti Radhiah’s modern attitude towards food and her advocacy of women’s education and progress, they were also a medium through which she could voice the importance of enlarging the scope of Malay literature so that it would serve the needs of women who were interested in domestic science.

Early Life

Siti Radhiah’s cookbooks do not provide much biographical information about her, and we do not know the year she was born. We can only surmise that she was likely born in Selangor. It is only in her second book, Hidangan Wanita Sekarang, that she was described as a graduate of Selangor Malay School, a former teacher of Kuang Malay School in Selangor and the wife of Harun Aminurrashid who was also a writer.

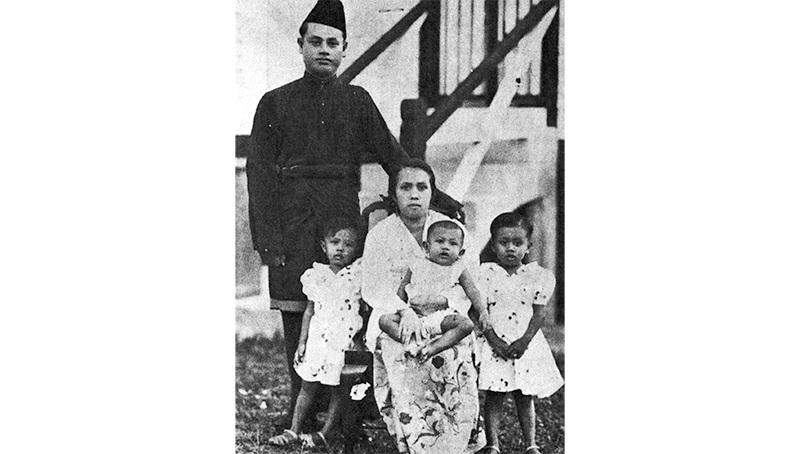

Much of the information about Siti Radhiah in this essay has been gleaned from the biographies about her husband Harun Aminurrashid – who gained a reputation over time as a renowned educator, writer, editor, publisher and political activist from Singapore – whom she married in the 1930s.3 Together, they had 15 children. Siti Radhiah was once a teacher. She likely chose this career because there were not many options available to Malay women at the time. Her father, Mohamed Saleh, was the principal of Serendah Malay School in Selangor.

In 1939, Siti Radhiah and her family moved to Brunei when Harun was transferred there as Superintendent of Education. He had in fact been banished there by the British colonial authorities for his nationalist teachings as a teacher at the Sultan Idris Training College in Tanjung Malim, Perak.4 While in Brunei, Siti Radhiah lost her fifth child, and gave birth to her sixth and seventh children.5

When the British returned upon Japan’s surrender in 1945, Siti Radhiah’s husband was imprisoned without trial by the British Military Administration, the interim administrator of British Malaya, for 86 days as he was accused of colluding with the Japanese.

During this time, Siti Radhiah and her children found refuge with the Kedayan, one of the indigenous peoples of Borneo. When her husband was later found not guilty, he was first offered a position as a member of the state executive council for Ulu Yam in Selangor, and then a teaching position in Singapore. He turned down both appointments as he had lost faith in the British colonial authorities and wanted nothing to do with them. In 1946, Siti Radhiah and her family moved to Singapore, where she and her husband became involved in the writing and publishing industry.6

A Mission to Spread Knowledge

Encouraged by the success of her first cookbook, Hidangan Melayu, published in 1948, Siti Radhiah went on to write a second one in 1949.7 In the preface she wrote:

“Since my first book titled ‘Hidangan Melayu’ was well received by my female readers, here I attempt to arrange and write a cookbook of kuih to develop our library. For the contents of this book, I have compiled [recipes for] new styles of kuih that I have tried, which were taught to me by my friends who are experts at making kuih, and found to be nice. Since I feel that it would be good to share this knowledge, I have compiled [the recipes of] as many as 50 kinds of kuih for my sisters who would love to try them too… Hopefully, [this cookbook] will become a bit of a service to my bangsa [nation], particularly to the women.”8

Siti Radhiah regarded cookery as an important body of knowledge that needed to be documented and disseminated. Attuned to the culinary trends of the period, she compiled recipes that were in vogue in the Malay world at the time. In the process of writing her cookbooks, she employed the same method of gathering information: by learning from women who were good cooks and knowledgeable about cookery, and trying out and testing their recipes.

For her third cookbook, Memilih Selera, published in 1953, Siti Radhiah obtained several of its 53 recipes from various Indonesian women. These women were most probably her friends.9

In 1957, Siti Radhiah’s fourth cookbook, Hidangan Kuih Moden, was published by Geliga Limited.10 It was the first instalment in the publishing company’s Women’s Series. By then, Siti Radhiah had graduated from a cookery course taught by a “Miss Asmah”. It is likely that she incorporated what she had learnt from Miss Asmah into this cookbook, which features modern recipes accompanied by photographs of cakes and tarts taken by her instructor.11

Being able to compile recipes from various culinary traditions suggests that Siti Radhiah belonged to a cosmopolitan community of like-minded women who were eager to share their culinary knowledge and uplift each other. Between September 1955 and September 1958, only 20 percent of the market for Malay books came from Singapore, compared to 75 percent from the Federation of Malaya, and the remaining 5 percent from Sarawak, Brunei and British North Borneo.12 Hence, Siti Radhiah’s cookbooks contributed to the corpus of works on domestic science and enabled knowledge about cookery to be shared publicly and to a wider audience, including those residing beyond the shores of Singapore.

Siti Radhiah saw her work of compiling recipes and writing cookbooks as a community service to the Malays, especially women, and the development of Malay literature and libraries as well as the preservation of Malay heritage. In the preface of her second cookbook, she used the term bangsa which refers to the Malay nation. Her contributions to the nationalist struggle against colonialism were aimed at elevating the position of Malay women by imparting valuable life skills, particularly modern methods of preparing food, through her writing.

Siti Radhiah further articulated this point in Memilih Selera, her third cookbook: “By having all kinds of information for mothers or for women published, it is one way to guide our women towards progress.”13 She also expressed concern over the dearth of books catered to Malay women, especially those written by Malay women, and exhorted other Malay women to share their knowledge by writing buku panduan (guidebooks or manuals) on various topics such as managing the household, taking care of the family, health, sewing, fashion and applying makeup.

In the early to mid-20th century, writing books was considered the domain of men, and there were very few female writers (regardless of race or ethnicity) in Singapore and Malaya. Between 1921 and 1949, female authors made up only 3.4 percent of the total number of Malay-language book authors in Singapore and Malaya.14 Cookery books, for instance, constituted a mere 4.8 percent of Malay non-fiction literature, which includes social science, history and politics, science and technology, and arts and culture within the same period.15 The first novel by a woman, Cinta Budiman (Sensible Love), by Rafiah Yusof, was published in Johor Bahru in 1941.16

In the publisher’s note in Memilih Selera, the publisher HARMY echoed Siti Radhiah’s sentiments about the need for more books targeted at Malay women: “A genre that is lacking in our literature is books on pengetahuan rumah tangga [domestic science] especially those related to the cookery or cuisine of our bangsa… Hopefully more books about cookery or domestic science will be published after [this cookbook] by Miss Siti Radhiah binti Mohamed Saleh.”17 It is possible that her husband Harun Aminurrashid, who founded HARMY with Raja Mohamed Yusof, the owner of Al-Ahmadiah Press, could have written the note.

In 1953, the same year that Memilih Selera was published, HARMY began producing Fesyen (Fashion), the first Malay weekly fashion magazine in Malaya, which became another avenue for Malay women to share and learn recipes through its recipe column, Dapur Fesyen (Fashion’s Kitchen).

It is highly likely that Siti Radhiah was encouraged by her husband Harun Aminurrashid to write because not only was he a prolific writer himself, he was also a keen supporter of women’s writings. He had earlier founded two magazines in 1946, Hiboran (Entertainment) and Mutiara (Pearl), which published most women’s writings in Malaya in the late 1940s and 1950s.18 Moreover, like Siti Radhiah’s cookbooks, Harun’s works also touch on women’s issues. For instance, his first novel, Melur Kuala Lumpur (Jasmine of Kuala Lumpur), published in 1930 broached the topic of female emancipation.19

While acknowledging that women should be educated, an article by Rahmah Daud in 1956 published in a special issue celebrating 10 years of Hiboran, edited by Harun, mentions that women’s struggle (perjuangan) for the nation began at home, and that they must fulfill their domestic responsibilities as wives, mothers and daughters first before venturing out to work in education, politics and other fields.20 According to a Fesyen article in 1954, women’s role had expanded after World War II from being the ratu dapur (“queen of the kitchen”) to the ratu rumah tangga (“queen of the household”), signifying that they were expected to be knowledgeable about and responsible for various household matters.21

A Taste for Modern Kuih

Siti Radhiah’s second book, Hidangan Wanita Sekarang, and fourth book, Hidangan Kuih Moden, feature the recipes for a smorgasbord of delicacies which she referred to as kuih cara baru (“new-fashioned kuih”), kuih zaman sekarang (“kuih of this time and age”) and kuih moden (“modern kuih”). She explained that many of the 50 recipes in Hidangan Wanita Sekarang closely followed the recipes and cooking techniques of Western cuisine.

Siti Radhiah saw how modern Western recipes – of assorted cakes, tarts, biscuits and puddings – could be adapted to fit into the traditional Malay culinary repertoire. She therefore encouraged her readers to increase the variety of kuih served in Malay homes especially during Hari Raya and other festive occasions. To Siti Radhiah, the modern Malay woman was not one who rejected kuih cara lama (“old-fashioned kuih”), but one who was not afraid to embrace new cooking styles so as to further develop her culinary know-how and expand her recipe collection.

In Hidangan Kuih Moden, the publisher Geliga remarked that Malay women were beginning to develop an appetite for new cooking methods. This cookbook, with its 65 recipes for “modern kuih”, appears to have been published in response to that growing interest amidst increasing acceptance of female education among Malay parents and exposure to domestic science as a subject.

Malay girls in vernacular schools began learning domestic science in Standard IV when they were around 10 years old. Inspector of Schools R.A. Goodchild commented in 1949 that enrolment at Malay girls’ schools in Singapore had risen steeply after the war, and since many Malay girls got married at 16 or 17 years old, infant hygiene, cooking and sewing formed an important part of their education. In 1949, the Straits Times reported: “Rochore Girls’ School, with only 40 students before the war, now has 140. The Kampong Glam Malay Girls School, with 400 pupils, has two school sessions each day to cope with the demand. Nine hundred Malay girls attended school in 1941. There are 3,000 today.”22 Lessons in domestic science would equip Malay girls with the skills for their future roles as wives, mothers and educators to their children.23

The postwar period also witnessed the birth of several women’s organisations, such as the Kaum Ibu (Women’s Section) of the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) and the Women’s Institute, which sought to improve the lives of Malay women – especially those living in rural areas who were uneducated – through literacy, sewing and cooking classes.24

At the same time, there was an increase in the number of schools and courses offering diplomas in domestic science and related subjects.25 Getting these qualifications enabled Malay women to become domestic science instructors in government schools, entrepreneurs who founded their own cookery schools as well as cookbook authors.26

Despite having already written three cookbooks, Siti Radhiah enrolled in a cookery course to further deepen her culinary knowledge, incorporating what she had learnt from the course in her fourth cookbook, Hidangan Kuih Moden.

As for Hidangan Wanita Sekarang, it included perennial favourites of modern Malay women at the time: marble cake, “roll cake” or Swiss roll with jam, oatmeal biscuit, kuih lapis (layer cake)27 and kuih semperit (a butter cookie usually in the shape of a dahlia flower and is also known today as biskut or kuih dahlia). In addition, there are a handful of variations of kuih lapis in these books, including lapis Betawi and lapis bumbu.

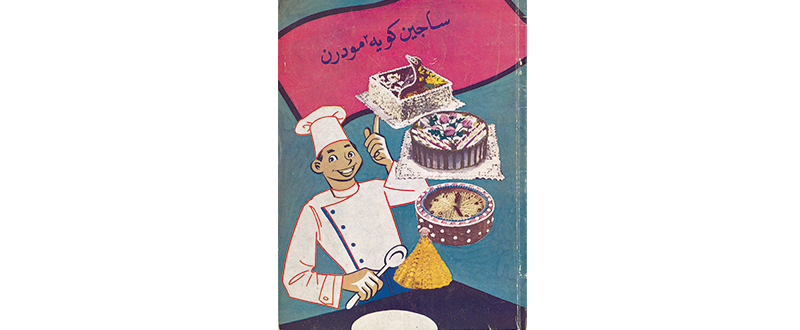

Unlike Hidangan Wanita Sekarang, which features a number of traditional Malay kuih such as dodol (a sticky confection made from glutinous rice flour, coconut milk and palm sugar) and wajik (a diamond-shaped snack made with steamed glutinous rice and cooked in palm sugar and coconut milk), Hidangan Kuih Moden has no recipes for these. Instead, it consists entirely of Western-style recipes.28 The book cover depicts a man in a chef’s uniform and illustrations of Western cakes.

This cookbook contains, for instance, several recipes that are of Dutch origin or have Dutch influences. In addition to kuih lapis, there are kaasstengel, a savoury cookie made with cheese, butter, wheat flour, egg yolks and baking powder, which is usually eaten during festive occasions in Indonesia today; and speculaas, a Dutch spiced cookie traditionally consumed just before or on Saint Nicholas Day.

Hidangan Kuih Moden also has many recipes for cakes with names such as “doll cake”, “butterfly cake”, “zig zag”, “double heart” and “magic cake”. An interesting recipe is for Kek Hari Raya (Hari Raya Cake), which is basically a butter cake with fondant poured and spread over it and then decorated with royal icing. But this has failed to become a Hari Raya staple.

Modern kuih was, however, not without its critics. In 1946, a Comrade correspondent using the pseudonym Orang Pelayaran (Sailor) lamented: “It is inevitable that in a cosmopolitan city like Singapore the Malays here have lost the art of making good old-fashioned Malay cakes and have taken to [W]estern cakes.” Comparing the situation in Singapore with that in Malaya, he wrote: “But in the Union, the art is not lost, though taste[s] may have changed.”29

An Appetite for Culinary Diversity

Moving away from kuih, Siti Radhiah’s third cookbook, Memilih Selera, contains 53 recipes for lauk-pauk (lauk refers to a dish that is eaten with rice; lauk-pauk means an assortment of lauk). In the preface she wrote: “With the encouragement from my previous books, namely Hidangan Melayu and Hidangan Wanita Sekarang which have been celebrated by my Malay sisters, I have compiled a cookbook of lauk-pauk and I named it Memilih Selera. Hopefully, this book can be a companion to the sisters who would like to own it.”30

As mentioned earlier, several of these recipes were obtained from Indonesian women. Hailing from different parts of Indonesia such as Sumatra, Kalimantan and Java, these recipes make up a wide variety that include sate (satay, or grilled skewered meat), otak-otak (fish paste mixed with spices, wrapped in banana or coconut leaves and then grilled), soto (a soup comprising meat and vegetables), gulai and opor (both dishes are cooked in spices and coconut milk). Indonesian dishes with European influences such as bistik (beef steak), kroket (croquette) and pastel (a type of filled pastry like empanada and curry puff) are also featured.

Some of the dishes found in the cookbook, like sate and tahu goreng (fried tofu served with sweet and spicy sauce and ground peanuts), were already being sold by Javanese hawkers in Singapore before the 1950s.31 There were, however, a handful of dishes that might have been unfamiliar to some women living here and in Malaya such as basngek (besengek; grilled chicken cooked in spices and coconut milk) and gado-gado (a salad of boiled and raw vegetables, hard-boiled eggs, kerupuk or deep-fried crackers, and fried tofu dressed in peanut sauce) for which she included the romanised spellings. A dish called kari daging Brunei (Brunei meat curry) is also featured in this cookbook.

Siti Radhiah may have included recipes from Indonesia and Brunei because she viewed these dishes as part of the wider Malay cuisine. She embraced the cuisines of various groups which not only made up other parts of the Nusantara (Malay world) but had settled in Singapore for many decades as well.

It is interesting to note that the cover of Memilih Selera features a Western woman about to carve what looks like a turkey even though the cookbook features only a handful of Western-style recipes, none of which is for a roasted fowl. It was not uncommon for publications at the time, such as popular postwar magazines like Asmara, Aneka Warna and Fesyen, to portray images of Western women, especially Hollywood celebrities, as these appealed to younger readers and the masses in general.32

A Guide for Life

Due to its popularity, Hidangan Wanita Sekarang, Siti Radhiah’s second cookbook, first published in Jawi script in 1949, went through three reprints before it was published by the same publisher, Royal Press (also known as Pustaka Melayu), in romanised Malay script in 1961.33 This was done to cater to a wider audience which included non-Malay readers who were learning Malay but could not read Jawi.

In December 1961, Royal Press advertised its publication catalogue of 15 new titles in the Berita Harian newspaper, encouraging teachers to place their orders for supplementary reading books for the following school year. The publisher also urged that these books “must be read and studied by every National School student and students of bangsa asing [foreign nations] who [were] learning the National language [Malay]”.34

What is worth mentioning is that not only was Hidangan Wanita Sekarang the only culinary text in the series of new books – which aimed to “increase and widen knowledge as well as promote Malay literature with correct grammar”35 – Siti Radhiah was the only female author in the list, which includes her husband Harun Aminurrashid and other Malay authors such as Abdul Ghani Hamid, Shaharom Husain and Muhammad Ariff Ahmad (who was listed as “Mas”).

This cookbook, therefore, had its purposes expanded – from a culinary, educational, cultural and political text to incite the spirit of nationalism in Malay women and guide them towards progress, to a language text for non-Malay readers to learn the national language. Although the book was still being advertised in Berita Harian as late as 1969, it was no longer the sole culinary text as the list of new releases included a book about domestic science and another cookbook.36

It is interesting to note that this other cookbook, titled Aneka Selera (All Kinds of Tastes), was written by Siti Radhiah’s daughter, Siti Haida Harun, and published in romanised Malay in 1965.37 Siti Radhiah must have imparted her culinary skills and knowledge to her daughter. In the preface, Siti Haida acknowledges and credits her parents for the book:

“With encouragement from my mother, Siti Radhiah binti Mohd. Saleh the author of Hidangan Wanita Sekarang, Hidangan Melayu and other cookbooks, and encouragement from my father, Harun Aminurrashid, I have been able to write a cookbook from my experiences and the lessons [I took] on making kuih-muih and lauk-pauk. Hopefully, this book will be well received by our women.”38

In the later stage of her life, Siti Radhiah, true to her spirit of helping and learning from others, continued to share recipes through her submissions to Berita Harian’s column, Masakan Hari Ini (Today’s Dish). She died in 1983, three years before her husband’s passing in 1986.39

The author thanks Dr Geoffrey Pakiam for his assistance and advice.

Toffa Abdul Wahed is an Associate Librarian with the National Library, Singapore, and works with the Singapore and Southeast Asia collection. She was previously a research assistant (2018–20) for a project titled Culinary Biographies: Charting Singapore’s History Through Cooking and Consumption, funded by the National Heritage Board’s Heritage Research Grant.

Toffa Abdul Wahed is an Associate Librarian with the National Library, Singapore, and works with the Singapore and Southeast Asia collection. She was previously a research assistant (2018–20) for a project titled Culinary Biographies: Charting Singapore’s History Through Cooking and Consumption, funded by the National Heritage Board’s Heritage Research Grant. NOTES

-

Her name has also been spelled “Radiah” and “Radziah”, and her father’s name has also been spelled “Salleh”. For this essay, I have used the spelling “Radhiah” and “Saleh” from Siti Haida Harun’s cookbook. ↩

-

According to Christopher Tan, food writer and author of The Way of Kueh (2019), the word kueh or kuih refers to a diverse variety of sweet and savoury foods and snacks. Kuih is the formal spelling used in Malay today. I have used this spelling to replace all instances of kueh mentioned in the materials consulted for this essay, including Siti Radhiah’s cookbooks. See Christopher Tan, “The Way of Kueh: Savouring & Saving Singapore’s Heritage Desserts,” (Singapore: National Heritage Board, 2019), 2. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 641.595957 TAN) ↩

-

Harun Aminurrashid, whose real name was Harun bin Muhamad Amin, was born in 1907 in Telok Kurau, Singapore. His other pen names include Har, Gustam Negara, Atma Jiwa and Si Ketuit. Besides writing textbooks and novels, Harun Aminurrashid was also the author of several publications, including Warta Jenaka, Warta Ahad, Hiburan and Warta Malaya. For a list of his works, see Abdul Ghani Hamid, Sebuah Catatan Ringkas Harun, Seorang Penulis (Singapore: Jawatankuasa Bulan Bahasa, 1994). (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. Malay RSING 899.2305 ABD) ↩

-

Sundusia Rosdi, “Harun Aminurrashid,” BiblioAsia 3, no. 2 (2007): 5. For more information about his time as a student and later a teacher at Sultan Idris Training College, see Abdullah Hussain, Harun Aminurrashid: Pembangkit Semangat Kebangsaan (Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, 2006), 20–39. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. R 899.283 ABD) ↩

-

Abdullah Hussain, Harun Aminurrashid: Pembangkit Semangat Kebangsaan, 32. ↩

-

Sundusia Rosdi, “Harun Aminurrashid,” 5–7. ↩

-

NLB does not have a copy of Hidangan Melayu. It is available at Arkib Negara (National Archives of Malaysia). See Siti Radhiah Mohamed Saleh, Hidangan Melayu, Arkib Negara, https://ofa.arkib.gov.my/ofa/group/asset/810802. Interestingly, the cookbook is also not listed in Md. Sidin Ahmad Ishak’s dissertation. [Note: The cookbook is not listed in a catalogue compiled by Md. Sidin Ahmad Ishak for his dissertation. See Md. Sidin Ahmad Ishak, “Malay Book Publishing and Printing in Malaya and Singapore 1807–1949,” vol. 2, PhD Diss. (University of Stirling, 1992), http://hdl.handle.net/1893/31182.] ↩

-

Siti Radhiah Mohamed Saleh, Hidangan Wanita Sekarang: Kuih-kuih Zaman Sekarang Untuk Hidangan Pada Ketika Minum Teh Petang Atau Pada Ketika Hari-hari Keramaian Atau Hari Besar (Singapore: The Royal Press, 1949), 4–5. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. Malay RCLOS 641.5 RAD). [Note: English translation by author.] ↩

-

Siti Radhiah Mohamed Saleh, Memilih Selera (Singapore: HARMY, 1953). (From National Library, Singapore, via PublicationSG) ↩

-

Siti Radhiah Mohamed Saleh, Hidangan Kuih Moden (Singapore: Geliga, 1957). (From National Library, Singapore, via PublicationSG) [Note: The cover of this cookbook reads Sajian Kuih2 Moden whereas its title page says Hidangan Kuih Moden. The different titles on the cover and title page might have been a printing error. For this essay, I have taken the title that appears on the title page.] ↩

-

Siti Radhiah Mohamed Saleh, Hidangan Kuih Moden, [n.p.]. Geliga Limited also published Sajian Pilihan (Selected Dishes) as the second instalment of the Women’s Series in the same year due to public demand. The publisher noted that the authors, Hamimah Mohamed and Rashimah Mohamed, had passed their cookery course at one of the cookery schools in Singapore. See Hamimah Mohamed and Rashimah Mohamed, Sajian Pilihan (Singapore: Geliga, 1957). (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. Malay RCLOS 640.2 HAM) ↩

-

Kartini Saparudin, “‘Colonisation of Everyday Life’ in the 1950s and 1960s: Towards the Malayan Dream,” (Master’s thesis, National University of Singapore, 2005), 16, https://scholarbank.nus.edu.sg/handle/10635/15580. ↩

-

Siti Radhiah, Memilih Selera, [n.p.]. [Note: English translation by author.] ↩

-

Before 1920, there were at least two female writers whose works were in the form of syair (traditional Malay poetry made up of four-line stanzas or quatrains). Three more female writers appeared on the scene in the 1920s, including Sophia Blackmore, a female missionary, who wrote Pelajaran Melayu (Malay Lesson) in 1923. See Md. Sidin Ahmad Ishak, “Malay Book Publishing and Printing in Malaya and Singapore 1807–1949” vol. 1, PhD. Diss., (University of Stirling, 1992), 132–133, 175–78. ↩

-

Md. Sidin Ahmad Ishak, “Malay Book Publishing and Printing in Malaya and Singapore 1807–1949,” vol. 1, 213–216. ↩

-

Md. Sidin Ahmad Ishak, “Malay Book Publishing and Printing in Malaya and Singapore 1807–1949,” vol. 1, 175. See also Alicia Izharuddin, “The New Malay Woman: The Rise of the Modern Female Subject and Transnational Encounters in Postcolonial Malay Literature,” in The Southeast Asian Woman Writes Back: Gender, Identity and Nation in the Literatures of Brunei Darussalam, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia and the Philippines, ed. Grace V.S. Chin and Kathrina Mohd Daud (Singapore: Springer, 2019), 57. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 809.8959 SOU) ↩

-

Siti Radhiah Mohamed Saleh, Memilih Selera, [n.p.]. ↩

-

Alicia Izharuddin, “The New Malay Woman,” 57. ↩

-

NLB has the 1962 edition. See Harun Aminurrashid, Melur Kuala Lumpur (Singapore: Royal Press, 1962). (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. Malay RCLOS 899.2305 HAR). ↩

-

Rahmah Daud, “Wanita Dengan Rumah Tangga,” in Hiboran 10 Tahun 1946–1956, ed. Harun Aminurrashid (Singapore: Abdullah Ali, 1956), 81. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. Malay RCLOS 059.9928 H) ↩

-

“Soal Kuih-muih Melayu,” Fesyen (4 July 1954): 4. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. Malay RCLOS 391.005 F) ↩

-

“Hygiene Among Malay Mothers,” Straits Times, 11 January 1949, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

It was reported in 1949 that four English and two Malay schools in Singapore were training more than 1,000 girls between the ages of 11 and 16 in domestic science. See “Making School Girls Better Wives,” Singapore Free Press, 28 March 1949, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lenore Manderson, “The Shaping of the Kaum Ibu (Women’s Section) of the United Malays National Organisation,” Signs 3, no. 1 (Autumn 1977): 210–28. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Opened in 1947, Tenaga Murni at Onan Road was the first tailoring school for Malay women in Singapore. Recipes by its students were frequent features in Fesyen’s recipe column. Another of such school was Borneo Tailoring School located at 200 Joo Chiat Road. Despite its name, it was popular among Malay women who learned how to make Western cakes there. These schools also attracted students from other parts of British Malaya as well as Brunei. See “Malay Women Take Up Tailoring & Embroidery,” Straits Times, 27 January 1949, 5; “190 Girls Attend Tailoring School,” Straits Times, 14 March 1951, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

In 1950, the first batch of teachers completed their training in domestic science at the Domestic Science Centre for Malay Women Teachers at Kuala Kangsar, Perak. The teachers were then posted to schools to teach domestic science to students from Standards IV to VI. See “Domestic Science Centre in Perak,” Indian Daily Mail, 12 June 1950, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

For more information about the different types of kuih lapis, see Christopher Tan, “Love is a Many-layered Thing,” BiblioAsia 16 no. 4 (Jan-Mar 2021). ↩

-

Interestingly, instead of using glutinous rice flour, Siti Radhiah’s recipes for dodol and wajik use potato instead. In the recipe for dodol kentang (kentang is potato in Malay) which involves making potato flour, she wrote: “Potatoes are sliced thinly, left to dry, pounded into a fine flour. Pandan leaves are pounded, squeezed with coconut [milk] then mixed with potato flour and sugar. Lastly, place into a wok, cook until it thickens.” To make wajik kentang, she wrote: “Potatoes are sliced thinly. [Coconut] is grated, mixed with sugar [then] cooked. [Then] add the potatoes and cook by stirring until [the mixture] dries. [After] it is cooked, add a bit of vanilla then remove [from stove].” See Siti Radhiah Mohamed Saleh, Hidangan Wanita Sekarang, 9–10. ↩

-

“Around Malaya,” Comrade, 4 November 1946, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Siti Radhiah Mohamed Saleh, Memilih Selera, [n.p.]. [Note: English translation by author.] ↩

-

N.A. Canton, J.L. Rosedale and J.P. Morris, Chemical Analyses of the Foods in Singapore (Singapore: Authority, 1940), 161–163, 166. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RRARE 664.07 CAN; Microfilm no. NL8059) ↩

-

Kartini Saparudin, “‘Colonisation of Everyday Life’ in the 1950s and 1960s”, 34–36. ↩

-

In the advertisements of the publication catalogue that the Royal Press ran in Berita Harian between 1961 and 1964, this cookbook was the only culinary literature on the publisher’s list despite the interest in cookery among Malay women. ↩

-

“Halaman 5 Iklan Ruangan 1,” Berita Harian, 5 December 1961, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Halaman 10 Iklan Ruangan 4,” Berita Harian, 1 November 1969, 10. (From NewspaperSG). ↩

-

Siti Haida Harun, Aneka Selera: Kuih-kuih dan Lauk-pauk Pilihan Selera (Singapore: Malaysia Press, 1965). (From National Library, Singapore, via PublicationSG) ↩

-

Siti Haida Harun, Aneka Selera, [n.p.]. [Note: English translation by author.] ↩

-

“Anumerta Kenang Jasa Harun,” Berita Harian, 17 July 1995, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩