A History of The Padang

Kevin Tan looks at what makes the 4.3-hectare patch of green in front of the former City Hall building so special.

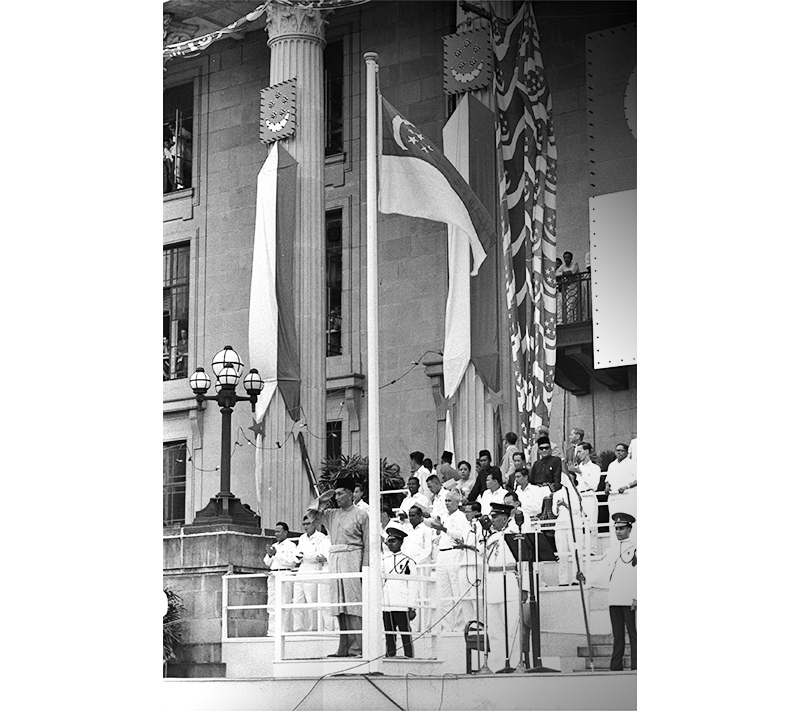

The Padang occupies a special place in Singapore’s history. Younger Singaporeans know it as the traditional site for many National Day Parades while older Singaporeans will remember it as the venue for the installation of Yusof Ishak as Yang di-Pertuan Negara (Malay for “Head of State”) in December 1959. Four years later, it was at the Padang that founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew announced Singapore’s merger with Malaysia. A little further back, in September 1945, a victory parade was held at the Padang to commemorate Japan’s formal surrender following the end of World War II.

Given the many historic events associated with the site, there is little doubt that the Padang deserves to join Singapore’s list of national monuments. However, it was only after the Preservation of Monuments Act was amended in November 2021 to expand the definition of monument to include sites that the Padang could be designated as a national monument. The gazetting of the Padang as a national monument will safeguard the 4.3-hectare site for future generations of Singaporeans.

Early History

The earliest written reference to the Padang, which means “field” in Malay, is found in the 17th-century Sulalat al-Salatin (Genealogy of Kings),1 better known as Sejarah Melayu or Malay Annals. The Sejarah Melayu refers to it as “the plain near the mouth of the river Tamasak [Temasek]”.2 Sang Nila Utama, a Srivijayan prince from Palembang, is said to have spotted the legendary singa (lion) on the Padang in the 13th century while on an expedition to Bentan (Bintan). Awed and inspired by what he saw, Sang Nila Utama decided to establish a kingdom on the island of Temasek in around 1299. He named it Singapura (Sanskrit for “Lion City”).

Five hundred years later, on the afternoon of 28 January 1819, Stamford Raffles and William Farquhar of the British East India Company landed at the mouth of the Singapore River, went ashore and met Temenggong Abdul Rahman, the local chief of Singapore. The temenggong gave Farquhar a free hand as to where to pitch his tents and Farquhar picked the plain, saying: “I think the best place is here on this open space.” Farquhar’s men then offloaded their tents and provisions, cleared the plain of scrub and bushes and set up camp. The next morning, they erected a 30-foot flagpole and hoisted the Union Jack. The writer Munshi Abdullah noted that at the time, most of the island was covered in thick jungle, save for the middle of the open space which “only had myrtle, rhododendron and eugenia trees”.3

On 6 February 1819, in the presence of Farquhar, the temenggong and a company of sepoys, Raffles signed a treaty with the newly installed Sultan Husain Mohamed Shah of Singapore that allowed the British to establish a trading post on the island.4 At the time, the southeastern edge of The Plain – as the Padang was then known – formed part of Singapore’s original shoreline. It was only after land was reclaimed from the sea along this shoreline in 1889 that The Plain achieved its current width.

For the first few years, this open ground, which was initially used as the Sepoy Lines to house troops, was known as The Cantonment. Later, it was simply referred to as The Plain.5 In 1831, it became known as the Esplanade until the turn of the 20th century when the field was commonly referred to as The Padang.6 William Daniell’s 1830 aquatint etching, View of Singapore Town and Harbour from Government Hill, gives us an idea of what the Padang would have looked like at the time.7

A Colonial Playground

For the first 10 years after Raffles’ arrival, the Plain was simply a swathe of green abutting the beach.8 The public would flock to the Plain for casual recreation, especially in the evenings. Games, horse races and band performances were held for the public’s enjoyment. One of the earliest ceremonies to take place there was the firing of the salute by the artillery on 23 April 1824 to commemorate the king’s birthday, while the earliest recorded band performance was in June 1831 when the band of the Madras Native Infantry visited Singapore.9

From January 1841, the Esplanade, the name it was then known by, became the regular venue for New Year’s Day celebrations. Off the coast, a regatta was staged, and on land, a variety of events were held. These included grease-pole climbing competitions, pony races, foot races, soccer matches and dance performances.

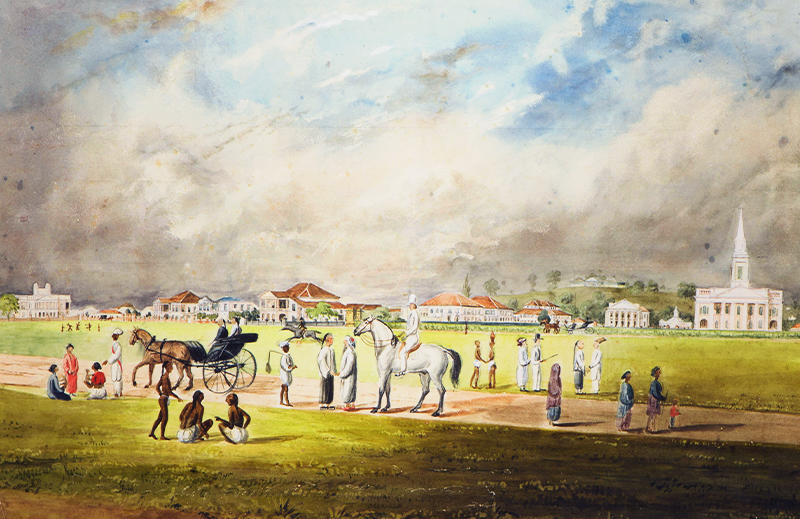

In his famous oil painting, The Esplanade from Scandal Point, John Turnbull Thomson – Singapore’s first Government Surveyor – recorded an evocative scene of how it would have looked like around 1851. (Thomson had, in fact, depicted a similar scene in his earlier painting simply titled The Esplanade 1847.)

By the late 1840s, the Esplanade was a busy place. Indeed, it grew so crowded that in 1845, the Municipal Committee, fearing for the safety of users, especially young children, decided to enclose it with bollards and chains to protect the “green sward” from “the incursions of pony-racing drunken sailors”.10

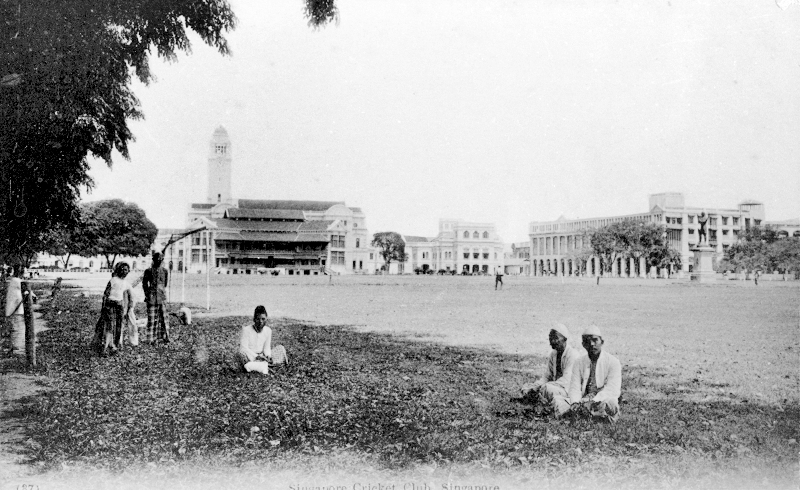

The Esplanade’s open, green space lent itself naturally to cricket matches. In 1837, there was a report of objections to some Europeans playing the sport at the Esplanade on Sundays.11 In 1852, a meeting was held to establish the Singapore Cricket Club and a small pavilion was erected at the western end of the Esplanade as a clubhouse for the new club.12 This pavilion was later rebuilt in the 1870s and then again in 1901, after which the building acquired much of its current form.

The Singapore Recreation Club, which occupies the eastern end of the Esplanade, had its new clubhouse declared open by then Governor of the Straits Settlements John Anderson and his daughter on 2 September 1905.13 The club building, albeit renovated many times over the decades, is still located there today.

Centre of Imperial Power

The Padang’s emergence as Singapore’s most important colonial civic space was organic, rather than by design. If it was intended as a maidan – the Persian term for a planned urban field around which major official buildings were built, as can be found in India and Penang – as architectural historian Lai Chee Kien argues,14 then that planning came very late in Britain’s colonisation of Singapore, almost 100 years after Raffles first set foot on the island.

Raffles had instructed that the north bank of the Singapore River be reserved for civic and public purposes, but his plan was thwarted when Farquhar allowed Europeans to build their private residences on the fringe of the Padang. One of these houses was later converted into the London Hotel, and subsequently renamed Hotel de l’Esperance and thereafter as Hotel de l’Europe.15

The first move in transforming the Padang into a centrepiece of British power was the Municipal Commission’s (formerly the Municipal Committee) acquisition of part of the Hotel de l’Europe site nearer the junction of Coleman Street in 1899 for its new Municipal Building.16 Due to World War I and other delays, the new Municipal Building (renamed City Hall in 1951) was completed only in 1929.

Hotel de l’Europe was demolished in 1900 and rebuilt as Grand Hotel de l’Europe, which was completed in 1905. In 1932, the once-great hotel went bankrupt and the government acquired the site two years later to construct the Supreme Court to replace the old Court House (The Arts House today), which had been built in 1827 as a residence for Scottish merchant John Argyle Maxwell and renovated many times over.17

The Padang’s formal appearance was aided by its enlargement in 1859, its encirclement by Connaught Drive and St Andrew’s Road, and its framing by the Singapore Cricket Club on one end and the Singapore Recreation Club on the other. However, it was not until the late 1930s – with the completion of the Municipal Building in 1929 and the Supreme Court in 1939 – that the Padang and its surrounds became a symbol of British colonial power. This transformation took half a century.

In the years leading up 1939, the Padang bore witness to many events and installations that reinforced its significance as a civic centre and symbol of colonial authority. Probably the most significant was the celebration of the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria’s reign on 27 and 28 June 1887, which included a carefully planned and precisely executed military pageantry followed by sporting events, religious services, processions, and culminating in a grand ball at Government House (now Istana) on 28 June.18

The highlight of the day’s events on 27 June was the unveiling of Raffles’ statue by then Governor of the Straits Settlements Frederick Weld to serve as “a permanent memorial of the Jubilee”. Located at the “centre of the sea side” of the Esplanade,19 the eight-foot-tall (2.4 m) bronze statue was cast by famed British sculptor-cum-poet Thomas Woolner who had “carte blanche” for its construction. (Frequently, and somewhat ingloriously, hit by stray footballs during matches, the statue was eventually moved from the Esplanade to Empress Place on 6 February 1919 as part of Singapore’s centenary celebrations.20)

After the British surrendered to the Japanese on 15 February 1942, the Padang became the site for the display of Japanese imperial power.21 The Municipal Building was commandeered by the Syonan Tokubetsu-si (Municipal Administration) as the headquarters of the civil administration. During the Japanese Occupation, the Padang continued to serve as a parade and ceremonial ground.

The official programme for the Tentyo-Setu (Emperor’s birthday) published on 28 April 1942 reported that “schoolboys will march to the Municipal Building; and that at 11 am, Mayor Shigeo Odate will appear on the balcony of the building to shout three ‘Banzais’ and make a speech”.22 In a public display of comity with Indian nationalism, Japanese Prime Minister Tojo Hideki and Indian National Army (INA) leader Subhas Chandra Bose reviewed a parade mounted by INA troops on 6 July 1943 in front of 25,000 spectators.23

Beyond ceremonial events, the Japanese took a practical attitude towards the Padang. On 17 February 1942, shortly after the fall of Singapore, they used it as an assembly ground to hold and interrogate the European population – civilians and prisoners-of-war – before marching them off to internment camps in Changi and Katong.24 In 1944, the Padang was turned into a plot for planting tapioca as part of the Grow More Food Campaign which proved ultimately futile.25

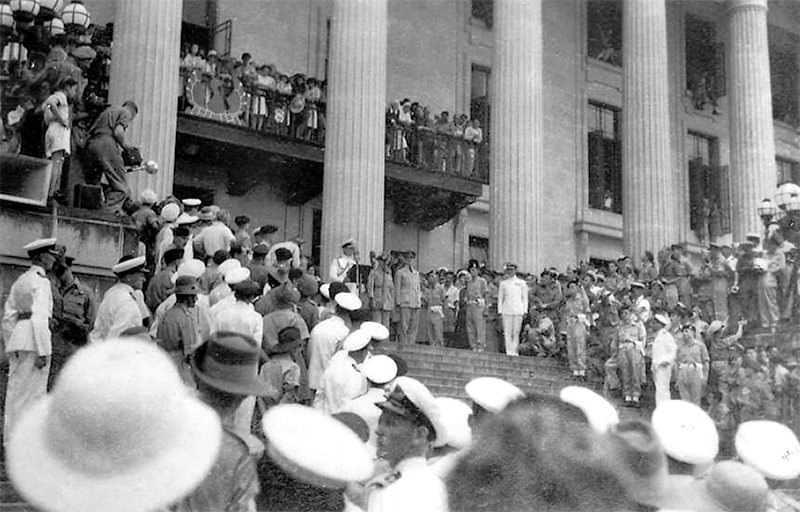

After the British reimposed its authority on Singapore, it celebrated the end of the war with a grand surrender ceremony at the Municipal Building and a military parade at the Padang in September 1945. On 12 September 1945, before the surrender ceremony, Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, Supreme Allied Commander Southeast Asia, inspected the parade, “stopping here and there to talk to a British marine, a Dogra, a Punjabi, a British soldier and a French soldier”.26

Of Contestation and Confrontation

Given the Padang’s role at the heart of British colonial power, it comes as no surprise that it was also the site of confrontation, rallies, protests and demonstrations. The first confrontation was silent but deeply symbolic. On 6 January 1946, a contingent of 16 guerrilla leaders of the Malayan Resistance Movement, led by Chin Peng, received the Burma Star and the 1939–45 War Medal from Mountbatten at an award ceremony. As they did so, 11 of them gave silent clenched-fist salutes. Two years later, the Malayan Communist Party, led by Chin Peng, launched its anti-colonial armed struggle from the Malayan jungle.27

The Padang was also where the Maria Hertogh riots first erupted. On 11 December 1950, “mob violence broke out… in front of the Supreme Court” at around 1 pm over an appeal related to the custody lawsuit of Maria Hertogh. “Two Malays were shot, and several other Malays and Muslims were injured.”28 Riots broke out throughout the city and when law and order was finally restored on 13 December, 18 people had died and 173 injured.29

Because it was so easy to stage large rallies and gatherings at the Padang, it was just as easy to capitalise on these huge crowds to foment trouble. Take the 1963 protest rally organised by the Chinese Chamber of Commerce, for example. Held on 25 August, the rally was organised to demand reparations from Japan for its wartime atrocities. A massive crowd of some 120,000 people – reportedly one of the largest in Singapore’s history – gathered at the Padang.30 In the run-up to this rally, the Special Branch and the Criminal Investigations Department discovered that pro-communist elements planned to exploit the meeting to stage an anti-Malaysia campaign. The entire police force – 5,000 men and troops – was placed on emergency alert.31

As then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew started speaking, the agitators began their organised booing. Lee challenged them to “come up to the City Hall and present their case” and then ordered floodlights to be turned on the several thousand pro-communist elements who had “formed a belt from one end of the Padang to the other”.32 The booing died down and the agitators faded into the crowd. A potential public order disruption had been averted.

The People’s Padang

In 1959, Singapore became a self-governing state after the People’s Action Party won the much-anticipated and fiercely contested general election on 30 May 1959 by a huge margin. Speaking at a victory rally on the steps of City Hall on 3 June, Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew told the crowd that his party had planned election rallies at the Padang at night but could not have them because “a small group of Europeans who were given this field by the former Colonial Government, refused it, although they only use it in the day time for a few people to play games”. “Well,” he noted, “times have changed, and will stay changed.”33

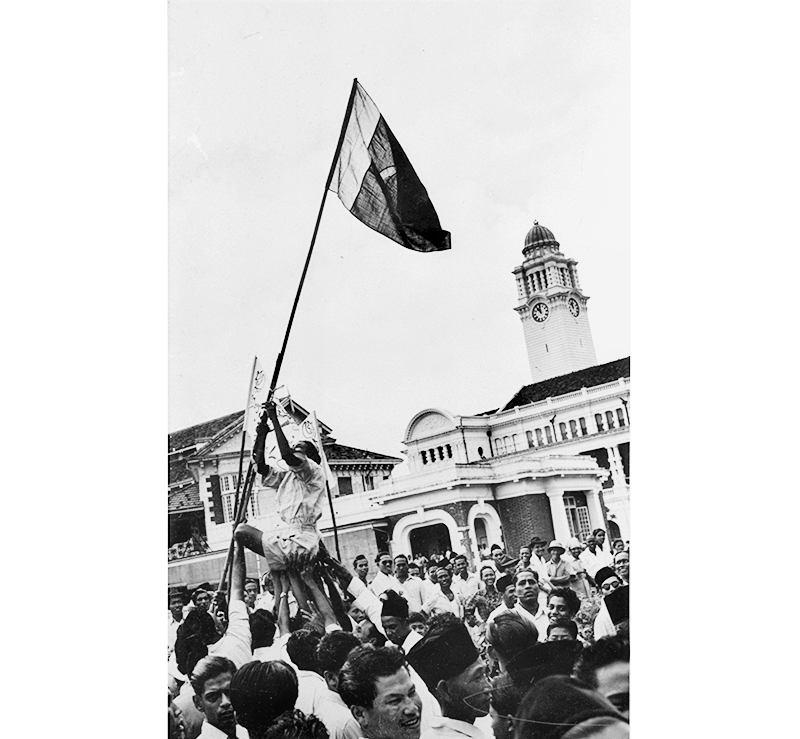

From 3 to 10 December 1959, this zeitgeist was translated into National Loyalty Week, a campaign to evoke a sense of loyalty and patriotism in the citizens of the newly self-governing state. By 8 am on 3 December, a crowd of 10,000 had gathered at the Padang. Inside City Hall, Yusof Ishak was sworn in as Singapore’s first Malayan-born Yang di-Pertuan Negara in a historic nine-minute ceremony. Following a 17-gun salute, the state flag was unfurled for the first time and the “huge crowd which jammed the Padang and its approaches… down Nicoll Highway, stood and joined in the singing of the new national anthem”, Majulah Singapura, composed by Zubir Said. A big march-past lasting over an hour followed.34

At the conclusion of National Loyalty Week on 10 December, a star-studded Aneka Ragam Ra’ayat (People’s Cultural Concerts) was held on the steps of City Hall. These shows featured a multiracial and multicultural programme with the hope that a new Malayan culture would emerge through “the interaction of our rich and varied cultures”.35

The Padang was also witness to a pivotal moment in Singapore’s history: merger with Malaysia. After many rounds of fraught and complex negotiations over the terms of the merger, an agreement was finally signed on 9 July 1963. On 31 August 1963, Prime Minister Lee unilaterally declared Singapore’s de facto independence at the Padang as “trustees for the Federal Government (in) these 15 days”.36

Two weeks later, on Malaysia Day, Prime Minister Lee spoke at the Padang again in front of thousands of people. His voice shaking with emotion and with tears welling up in his eyes, he declared his hope, in a 275-word proclamation, that the merger would be “a relationship between brothers, not a relationship between master and servant”.37 However, the relationship was not a happy one, and on 9 August 1965, Singapore separated from Malaysia and became an independent and sovereign nation.

A Place for the Nation

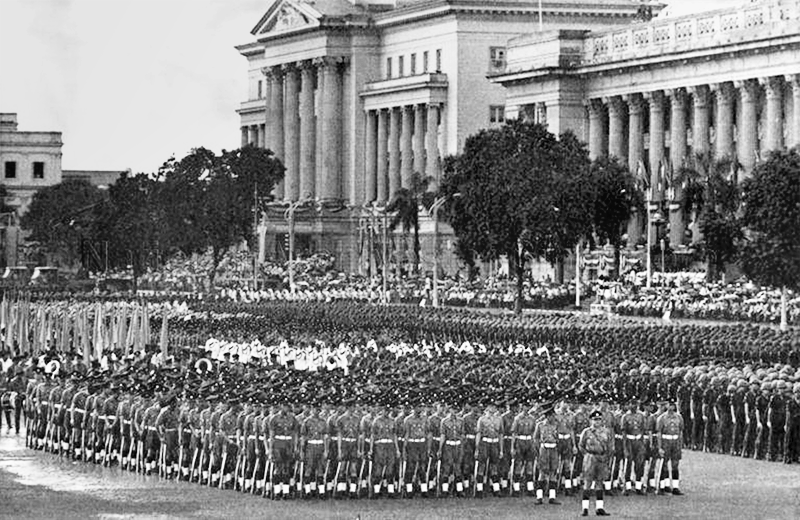

When Singapore celebrated its first anniversary as an independent state with a parade on 9 August 1966, it was only natural that it be held at the Padang. Over 23,000 Singaporeans took part in the parade which began at 9 am (parades were held in the evening from 1973 onwards). Six contingents of the People’s Defence Force were on parade, and four government ministers marched as officer cadets in that contingent.38 It was a simple but momentous parade that instilled great pride in the new nation. Two years later, in 1968, it became “a gigantic display of the rugged society” as an hour-long downpour pelted the parade formations and spectators relentlessly.39

As an independent state, Singapore continued to use the Padang as a major parade ground and gathering space to galvanise the people, instil pride in them and rally them to a cause. It comes as no surprise that it was the sole site for the annual National Day Parade (NDP) for the next 10 years. It was only in 1975 that decentralised parades were held, but the main parade returned to the Padang every few years.

Other than the NDP, the Padang continues to be the venue for sporting events at local, regional and international levels. For many years, the finals of the inter-school rugby competition were held at the Padang, which is also home to the Singapore Cricket Club International Rugby 7s.40

The Padang was also the backdrop to the world’s first-ever nighttime Formula 1 Grand Prix. During the inaugural race on 14 September 2008 – as Fernando Alonso raced around the 5.06-kilometre Marina Bay Circuit to clinch first place – images of the Padang were beamed live into living rooms across the world.41 Singapore had truly come of age as a global city and destination.

Given its age, historical significance and global prominence, it is timely that the legislation has been amended to allow the Padang to take its place on the list of Singapore’s national monuments.

Dr Kevin Y.L. Tan is Adjunct Professor at the Faculty of Law, National University of Singapore, and Visiting Professor at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University. He specialises in constitutional and administrative law, Singapore legal history and international human rights. He has written and edited over 50 books on the law, history and politics of Singapore.

Dr Kevin Y.L. Tan is Adjunct Professor at the Faculty of Law, National University of Singapore, and Visiting Professor at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University. He specialises in constitutional and administrative law, Singapore legal history and international human rights. He has written and edited over 50 books on the law, history and politics of Singapore.NOTES

-

Sulalat al-Salatin (Genealogy of Kings) is one of the most important works in Malay literature. It was likely composed in the 17th century by Bendahara Tun Seri Lanang, Prime Minister of the Johor Sultanate. ↩

-

John Leyden, John Leyden’s Malay Annals (Malaysia: MBRAS, 2001), 43. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 959.51 JOH) ↩

-

Munshi Abdullah, “The Hikayat Abdullah,” trans. A.H. Hill, Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 38, no. 3 (June 1955): 128, 130. (From JSTOR via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Munshi Abdullah, “The Hikayat Abdullah,” 137–141. ↩

-

Charles Burton Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1984), 286. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 959.57 BUC) ↩

-

“Our Esplanade,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 23 August 1900, 3; “Editorial,” Straits Times, 12 August 1903, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

This famous etching was published in Sophia Raffles, Memoir of the Life and Public Services of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, F.R.S. &c. Particularly in the Government of Java, 1811–1816, and of Bencoolen and Its Dependencies 1817–1824; with Details of the Commerce and Resources of the Eastern Archipelago, and Selections from His Correspondence (London: John Murray, 1830), 525. (From BookSG) ↩

-

For a depiction from the shoreline, see the painting titled Singapore, From the Esplanade by Captain Charles Ramsay Drinkwater Bethune published in James Augustus St John, Views in the Eastern Archipelago: Borneo, Sarawak, Labuan, &c. &c. &c. (London: McLean, 1847), 65. (Not available in NLB holdings) ↩

-

Buckley, Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore, 30. ↩

-

“Untitled,” Straits Times, 20 December 1848, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Roland St John Braddell, “The Good Old Days” in Walter Makepeace, Gilbert E. Brooke & Roland St John Braddell, eds., One Hundred Years of Singapore, vol. 2 (London: John Murray, 1921), 317. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RCLOS 959.51 ONE) ↩

-

Braddell, “Good Old Days,” 321. ↩

-

“Recreation Club,” Eastern Daily Mail and Straits Morning Advertiser, 4 September 1905, 3; “Singapore Recreation Club: New Pavilion Opened,” Straits Times, 4 September 1905, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lai Chee Kien, “The Padang: Centrepiece of Colonial Design,” BiblioAsia 12, no. 3 (Oct–Dec 2016): 40–4. ↩

-

Vernon Cornelius and Joanna H.S. Tan, “Former Supreme Court Building,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published 2011. ↩

-

“Municipal Commission,” Singapore Free Press, 17 May 1900, 10; “A Desirable Acquisition,” Singapore Free Press, 25 May 1900, 317. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Europe Hotel’s Future,” Singapore Free Press, 21 July 1932, 8; “Facilitation of Justice,” Morning Tribune, 2 April 1937, 24. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Jubilee Celebration, Singapore,” Straits Times Weekly, 29 June 1887, 7; “The Jubilee,” Straits Times Weekly, 6 July 1887, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Jubilee.” ↩

-

“Centenary of Singapore,” Straits Times, 7 February 1919, 27. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Constance Mary Turnbull, A History of Singapore, 1819–2005 (Singapore: NUS Press, 2009), 199. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 959.57 TUR) ↩

-

Turnbull, History of Singapore, 1819–2005, 205; “Tentyo-Setu Celebrations,” Syonan Shimbun, 30 April 1942, 5. (From NewspaperSG). [Note: Odate Shigeo was Mayor from March 1942 to July 1943. He was replaced by Naito Kanichi who held the office until the end of the Japanese Occupation.] ↩

-

Turnbull, History of Singapore, 1819–2005, 217–18; “With ‘Freedom or Death’ for Motto, Men Ready to Die for Indian Independence,” Syonan Shimbun, 9 July 1943, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Turnbull, History of Singapore, 1819–2005, 196–97. ↩

-

Lee Geok Boi, The Syonan Years: Singapore Under Japanese Rule 1942–1945 (Singapore: National Archives of Singapore and Epigram, 2005), 163 (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING q940.535957 LEE-[WAR]); Joshua Chia Yeong Jia, “Grow More Food Campaign,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published 2016. ↩

-

Turnbull, History of Singapore, 1819–2005, 221; “Japanese in Malaysia Surrender at Singapore,” Straits Times, 13 September 1945, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Guerrilla Leaders Decorated by Supremo,” Straits Times, 7 January 1946, 3. (From NewspaperSG); Shereen Tay, “Communist Party of Malaya,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published 30 March 2018. ↩

-

“2 Malays Shot: Cars Burnt,” Singapore Standard, 11 December 1950, 9; “Police Open Fire on Rioting Mob,” Malayan Tribune, 11 December 1950, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Maria Hertogh Riots,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published 28 September 2014. ↩

-

“Padang Rally: Big Security Alert,” Straits Times, 25 August 1963, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Padang Rally.” ↩

-

R. Chandran, F. Rozario, R. Pestana and Lim Beng Tee, “Lee Foils Bid to Spark Off Trouble at Rally,” Straits Times, 26 August 1963, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lee Kuan Yew, “Victory Rally at the Padang,” speech, 3 June 1959, transcript. (From National Archives of Singapore, Document no. lky19590603) ↩

-

“Singapore Rejoices,” Straits Times, 4 December 1959, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“A Memorable Week Ends,” Straits Times, 10 December 1959, 1; “Lee: We’ll Breed New Strain of Culture,” Straits Times, 3 August 1959, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Lee: We Are Free!,” Straits Times, 1 September 1963, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Lee’s Proud Moment,” Straits Times, 17 September 1963, 4; “Singapore Celebrates its Proudest Moment,” Straits Times, 17 September 1964, 15. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Chew Hui Min, “National Day Parade 1966: 10 Things About the Inaugural Parade,” Straits Times, 5 March 2015, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/national-day-parade-1966-10-things-about-the-inaugural-parade; “Day and Night of Joy and Fun in Singapore,” Straits Times, 10 August 1966, 1; “Ministers and MPs Seen in Uniform by Public for the First Time,” Straits Times, 10 August 1966, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Jackie Sam and Judith Yong, “The Rugged Society’s Day…,” Straits Times, 10 August 1968, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“About Us,” Singapore Cricket Club, accessed 15 February 2022, https://www.sccrugbysevens.com/. ↩

-

“Singapore – Marina Bay,” Formula One World Championship Limited, accessed 15 February 2022, https://www.formula1.com/en/information.singapore-marina-baystreetcircuit.7LXNQUCHTyR5yMQPlIk7Lv.html; “Do You Remember… F1’s First Ever Night Race,” Formula One World Championship Limited, 14 September 2015, https://www.formula1.com/en/latest/features/2015/9/do-you-remember—-f1s-first-ever-night-race.html. ↩