The Orang Seletar: Rowing Across Changing Tides

Singapore was once a home to the seafaring Orang Seletar who now reside in Johor Bahru. Ilya Katrinnada takes them on a tour around Singapore visiting Merlion Park, Sembawang Park and Lower Seletar Reservoir Park.

“I remember playing over there when I was a kid!” Atie1 exclaimed while pointing to the sea. A fisherwoman now in her late 30s, her wide eyes glinted with unmistakeable joy. Her excitement was matched by the 15 or so other people around us. Eagerly looking out the windows of the minibus, they chattered in their native Kon Seletar language as we drove along Yishun Dam, giving us a glimpse of Seletar Island, a place that is intimately tied to the history of the Orang Seletar.

Back in the 1980s and 90s, when Atie was a young girl swimming in the waters surrounding Seletar Island, the Orang Seletar travelled freely on their boats across the Tebrau Strait2 between Malaysia and Singapore. Today, more than 20 years later, Atie, together with some of her fellow Orang Seletar, were visiting Singapore again. Not by boat this time though. They were here as tourists, having travelled by land across the Causeway from their village of Kampung Sungai Temon in Johor Bahru, passing through both countries’ immigration checkpoints. My team member Chan Kah Mei and I played host.

This one-day tour3 in October 2019 around parts of Singapore – where they once lived – was the least we could do for them given the incredible hospitality they had shown us since we embarked on our research project in 2018 with another team member, Ruslina Affandi. We had set out to collect oral history interviews from the Orang Seletar, and were able to do so thanks to their time and generosity in sharing their stories.

"What’s Become of the Seafaring Orang Seletar?"

Who Are the Orang Seletar?

A nomadic sea people, the Orang Seletar4 have for centuries called the Tebrau Strait (Johor Strait) their home as they roamed along the mangroves, shores and rivers in the northern part of Singapore and on the southern side of peninsular Malaysia. They relied heavily on their multifunctional pau kajang – a wooden boat that typically houses a family of up to six people. Besides serving as a mode of transportation, the vessel was also their home – a place where they slept, cooked and played.

Each pau kajang had a thatched roof made of mengkuang (screw pine), or pandan leaves, that shielded its inhabitants from the relentless tropical sun and heavy rains.5 The distinct way the leaves were woven identified the Orang Seletar from other Orang Laut communities living around Singapore, such as the Orang Gelam who occupied the Singapore River, the Orang Kallang who situated themselves at the Kallang River, and the Orang Selat who travelled around the Southern Islands.

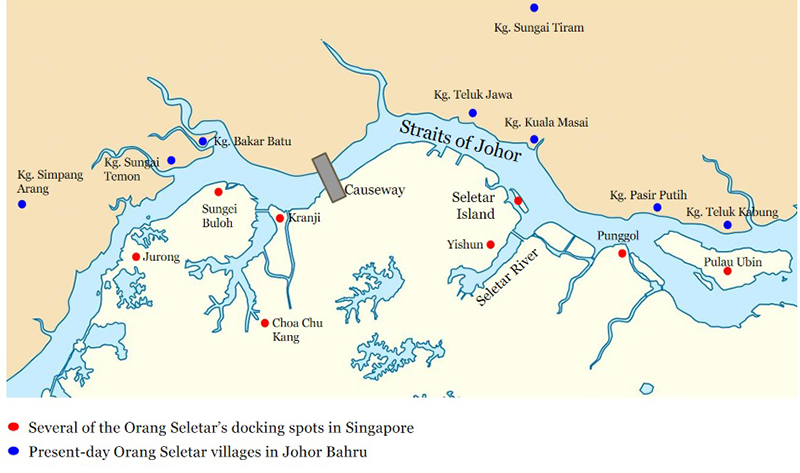

Periodically, families anchored their boats along the coastline. Besides Seletar Island (in the Johor Strait off the northern coast of Singapore), pit stops on the Singapore side of the strait included Jurong, Kranji, Choa Chu Kang, Punggol and Pulau Ubin. Here, they set up bente – temporary villages of small pile-houses where the community could gather. The Orang Seletar went wherever they could forage for their daily needs. Their intimate knowledge of the natural environment, passed down through generations, helped them navigate their surroundings, whether out at sea or in the mangrove swamps. They gathered tubers, wild yams and fruits, and dug crabs from the ground. With the help of their dogs, they hunted for wild boar. Fish were caught using handmade spears, and the surplus catch was traded for necessities such as cloth, rice and sago.

The Orang Seletar sourced crucial raw materials such as meranti (Shorea spp.) and seraya (Shorea curtisii)6 to build their pau kajang. They capitalised on the healing properties of mangrove plants to cure a variety of ailments, such as nyirih, which soothed skin conditions and healed the wound of the belly button of newborns. Historically animists, the Orang Seletar believed that spirits inhabited the world around them. They were respectful in their interactions with the environment, taking precautions to avoid disturbing any unseen beings.

Today, there are nine Orang Seletar settlements in Johor Bahru with a combined population of some 2,000. Many have adopted Christianity or Islam, and intermarriage outside of the community is not uncommon. In Singapore, the Orang Seletar have largely assimilated into the local Malay community. They used to reside in coastal villages, such as those at the mouths of the Kranji and Kadut rivers as well as Seletar Island, before these areas made way for development.7

An Indigenous People of Singapore

The minibus stopped at the roadside by the Merlion Park. As we were taking photos with the Merlion overlooking the Singapore River, our guests took out their handwoven tajak (headdress) to wear. We strolled by the river, eventually arriving at the statue of Stamford Raffles at Empress Place.

When Raffles first set foot on Singapore in January 1819, the Orang Seletar made up a fifth of the 1,000 or so inhabitants recorded by Raffles.8 It was also documented that there were about 20 to 30 Malays in the temenggong’s entourage at the time. The fact that the number of Orang Seletar and Malays were reported separately imply that the two were seen as distinct ethnic groups, despite similarities in their physical appearance. This still rings true today.

While the Orang Seletar refer to themselves as Kon Seletar or simply Kon, our interviewees said that it was the Malays who had given them the name “Orang Seletar”. Cultural geographer David Sopher suggests that the name Seletar is a Malay version of the Dutch term selatter which in turn was adapted from the Portuguese selat.9 Meaning “straits”, selat was adopted by writers in the 16th century to collectively refer to the different subgroups of sea nomads in the Melaka Strait. Hence, the presence of sea nomads in and around Singapore has been recorded as early as the 1500s.

The Orang Seletar have their own version of how the name Singapura came about. Several interviewees told us that their ancestors were hunting for wild boar on the island when they spotted a strange animal that looked like a lion. When Sang Nila Utama arrived in the 13th century, he had asked the Orang Seletar what the name of the island was. They replied “Singa Pulau” from which “Singapura” was derived.

Singapore’s Pioneer Generation

Our next stop was Sembawang Park. We walked to the beach which gave us a panoramic view of the southern end of Johor. “That’s Kilo’s village,” our guests told us. They pointed in the direction of the Orang Seletar village of Kampung Kuala Masai. The village and the beach were not only separated by the narrow body of water before us, but also by immigration checkpoints located about eight kilometres west of the Singapore-Johor Causeway.

The Causeway was completed in 1923, and the Orang Seletar were among those who helped in the construction. They also have dark stories about the structure. Kelah bin Lah, also known as Kilo, is a fisherman in his early 40s from Kampung Kuala Masai and a well-respected member of his village. He claimed that his grandfather had witnessed screaming young children being buried in the piling works of the Causeway during its construction. This was done because it was believed to strengthen the foundations of physical structures. As a result, Kilo’s father and uncle were advised to always have their children within sight and not allow them to go to school for fear that they would be kidnapped and sacrificed for the subsequent building of homes in the vicinity. After the Causeway was completed in 1923, the Orang Seletar continued to travel on their boats, utilising hidden tunnels on the underside of the bridge to cross from one side of the strait to the other.

The Orang Seletar were also involved in other ambitious development projects in Singapore’s early years, such as the clearing of mangroves in Jurong and Yishun for the construction of factories. Lel bin Jantan, an uncle of Kilo’s, spent five years in the 1960s working as a labourer in Singapore, doing piling work for the construction of houses in Geylang Serai, Jalan Kayu and Pasir Panjang, among others. In the 1970s, he lived on Seletar Island for about four years before he had to move as a reservoir was about to be constructed in the area. His baby son was buried there after succumbing to an illness.

Migration to Johor Bahru

The minibus pulled up at the entrance of Lower Seletar Reservoir Park. Kah Mei and I brought our guests to the bank of the reservoir, which was neatly lined with grey stones. To our right was a shallow, empty pool with fountain spouts, enclosed by terraced steps – likely a popular spot for young families on weekends. On our left was an expansive golf course.

We made our way to the boardwalk leading out to the reservoir. While walking, I could hear our guests talking about the fish in the water beneath us. Several informational panels on the boardwalk prompted us to stop. These panels provided an overview of the history of the area. The first panel paid homage to the communities who used to frequent the place, including the Orang Seletar.

“This is Tok Batin Buruk,”10 Jefree bin Salim said as he pointed to a black-and-white photo on the panel. Jefree had a camera in his hand, as he usually does. Having taught himself photography, Jefree has since been visually documenting the Orang Seletar community across the nine villages in Johor Bahru. A son of the headman of Kampung Sungai Temon, Jefree, who is in his early 40s, is active in advocating for the rights of his people and has contributed his images to court cases against commercial developers looking to gain control over the land that his village sits on.

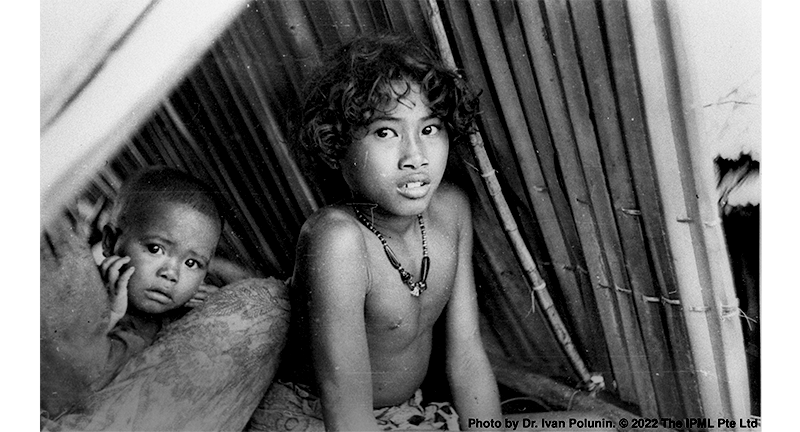

Taken at Seletar Island in the 1950s by Ivan Polunin, the photo depicts some Orang Seletar sitting atop their pau kajang. In the middle of the photo is Tok Batin Buruk, Jefree’s granduncle, who was the headman at the time. We were told that Tok Batin Buruk was a spiritually powerful man.

Jefree’s mother, Letih, told us that Tok Batin Buruk once used his spiritual prowess, along with a handkerchief, to help the then sultan of Johor court the Princess of Kelantan. This story reflects the close patron-client relationship between the Orang Seletar and the sultan in the past. Before World War II, they worked for the sultan, who paid them to catch crabs and fishes. They also often received invitations to the palace and accompanied the sultan on his hunting trips.

Tok Batin Buruk had a son, Entel, who is currently the village headman of Kampung Pasir Putih. Now in his mid-70s, Entel recalls living on Seletar Island for about two months when he was around 18 years old. He later applied to live on the island where his parents earned a living cutting mangrove wood for charcoal, but his application was unsuccessful.

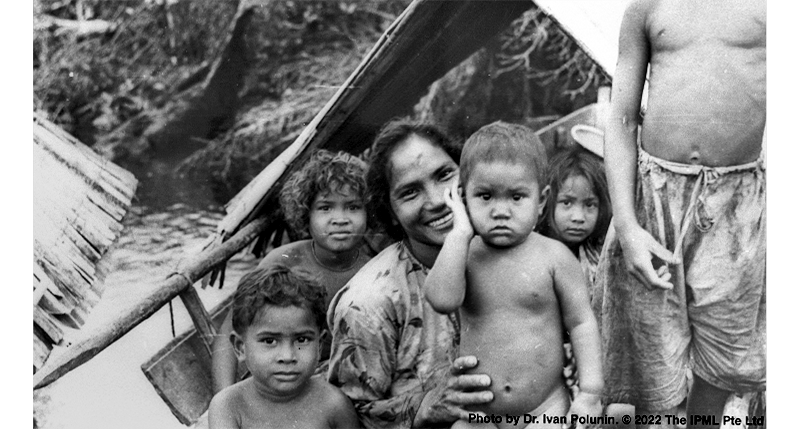

Entel’s younger sister, Mina, is in her early 60s. She has lived in Kampung Pasir Putih for more than 20 years. Together with her husband and her daughter’s family, they occupy a small concrete house right by the sea, rearing mussels and selling their catch for a living. Kah Mei, Ruslina and I visited them in 2018. From their patio, we could see a gigantic ship to the west, Singapore’s public-housing flats in the distance to the south, and a forested island a stone’s throw away to the southeast – Pulau Ubin. “I used to go there in a pau kajang,” Mina said. While Mina recalls spending time in Sungei Buloh, and on Ketam Island and Tekong Island, among other places, she told us that she had never been to Seletar Island. What she knew about the place came from stories related by her parents.

Living Histories

During their lifetime, the two siblings, Entel and Mina, have seen immense changes overtake their once-seafaring community. Their ancestors had the liberty of travelling freely along the Tebrau Strait, choosing where and when to row or dock their boats. Unfortunately, the Orang Seletar were eventually compelled to give up their nomadic lifestyle and move to settlements in Johor Bahru.

This turning point began in around 1948, during the Malayan Emergency, when the British government urged them to relocate to villages so as to control movement in the strait. According to anthropologist Clifford Sather, many families began spending their nights in self-built wooden houses at Kuala Redan (an estuary in Johor), and returning to their pau kajang to fish in the daytime.11 Another permanent settlement was established in Bakar Batu in the 1950s.

There were, however, families who chose not to settle on land but continued living in their boats. Anthropologist Mariam Ali writes that someone she spoke to mentioned the presence of many Orang Seletar on Seletar Island in around 1963 or 1965. Many moved out in around 1967 – after Singapore gained independence. Without any form of citizenship or identification cards, the Orang Seletar were afraid of being arrested by the police. Almost two decades later, in 1986, those still living in the Seletar area had to relocate due to further development projects.12

Up until 1987, the Orang Seletar who had taken up Malaysian citizenship were still granted unrestricted movement across the Tebrau Strait into Singapore territory, albeit unofficially. But following the arrest of an Orang Seletar who was exploited to smuggle illicit goods across the strait, Jefree said that they were no longer able to access Singapore waters. Although Jefree’s mother dates this incident to the 1980s, he recalls tagging along on fishing trips to Lim Chu Kang and Woodlands as a young boy in the 1990s. Interestingly, a relative of Jefree’s recently managed to fish at the Singapore side of the waters upon handing over his Malaysian identity card to the coastguards on duty. Once done, he retrieved his card from the guards before returning to his village in Johor.

Standing on the boardwalk at Lower Seletar Reservoir Park, it felt surreal to think that some of our guests and their ancestors had travelled here on their boats. This was back when the reservoir was a flowing river that drained into the Tebrau Strait. We walked to the end of the boardwalk to the large patio. Kah Mei and I helped our guests take a group shot – a rare modern-day photo of the Orang Seletar at what used to be the Seletar River.

.png)

The author is grateful that what had started out as an independent passion project turned into genuine, longstanding friendships. She would like to express her heartfelt thanks to her project teammates, Ruslina Affandi and Chan Kah Mei, as well as to the Orang Seletar who contributed to the project: Eddy bin Salim, Jefree bin Salim, Kelah bin Lah @ Kilo, Komeng, Letih, Lel bin Jantan, Tok Batin Entel, Tok Batin Salim bin Palun and Mina binte Buruk. Special thanks are also due to Jefree bin Salim for contributing photographs for this essay.

Kelah bin Lah @ Kilo (in white), Lel bin Jantan (in pink) and their family in Kampung Kuala Masai, Johor Bahru, 2018. Photo by and courtesy of Ilya Katrinnada.

Tok Batin Buruk’s daughter Mina (seated) and her husband (in white shirt) with their children and grandchildren at Kampung Pasir Putih, Johor Bahru, 2018. Photo by and courtesy of Ilya Katrinnada.

Ilya Katrinnada is an educator and writer with a keen interest in the intersections of creativity, community and education. Having graduated with a major in anthropology, she currently works as a special education teacher. She has also written about how the Orang Seletar live with nature in the Founder’s Memorial journal +65, which is published by the National Heritage Board.

Ilya Katrinnada is an educator and writer with a keen interest in the intersections of creativity, community and education. Having graduated with a major in anthropology, she currently works as a special education teacher. She has also written about how the Orang Seletar live with nature in the Founder’s Memorial journal +65, which is published by the National Heritage Board.NOTES

-

This name is a pseudonym. ↩

-

The Tebrau Strait is perhaps more popularly known as the Johor Strait. In the Kon Seletar language, the term tebrau refers to a big fish. ↩

-

The tour was part of a longer three-day visit, during which the Orang Seletar were invited to watch Tanah • Air 水 • 土:A Play in Two Parts by Drama Box. The play highlighted the displacement of the indigenous Malays and Orang Seletar of Singapore. ↩

-

The Orang Seletar are one of the 18 Orang Asli (indigenous people) ethnic groups in Malaysia. They are also part of the Orang Laut (Sea People), an umbrella term for the various groups of sea nomads who occupied the waters surrounding the Melaka Strait. The Orang Seletar refer to themselves as Kon and speak their own language. ↩

-

Amir Ahmad and Hamid Mohd Isa, “The Influence of Environmental Adaptation on Orang Seletar Cultures,” 7th International Seminar on Ecology, Human Habitat and Environmental Change in the Malay World, 27 January 2015, Repository University of Riau, https://repository.unri.ac.id/xmlui/handle/123456789/6662. ↩

-

Amir Ahmad and Hamid Mohd Isa, “The Influence of Environmental Adaptation on Orang Seletar Cultures.” ↩

-

Mariam Ali, “Singapore’s Orang Seletar, Orang Kallang, and Orang Selat: The Last Settlements,” in Tribal Communities in the Malay World: Historical, Cultural, and Social Perspectives, ed. Geoffrey Benjamin and Cynthia Chou (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2002), 273–92. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 305.8959 TRI) ↩

-

“1819 Singapore Treaty,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published 15 May 2014 ↩

-

Clifford Sather, The Orang Laut (n.p.: Academy of Social Sciences in cooperation with Universiti Sains Malaysia, Royal Netherlands Government, 1999), 12. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSEA 306.08095951 SAT) ↩

-

Tok Batin is a title used to refer to a village headman. This term was coined by the Malays, and is commonly used today. In the Orang Seletar language, the headman is called Pak Ketuak. ↩

-

Sather, The Orang Laut, 8. ↩

-

Mariam Ali, “Singapore’s Orang Seletar, Orang Kallang, and Orang Selat: The Last Settlements,” 273–92. ↩