No Longer “Dirty, Unhygienic, Crowded and Messy”: The Story of Singapore’s Changing Wet Markets

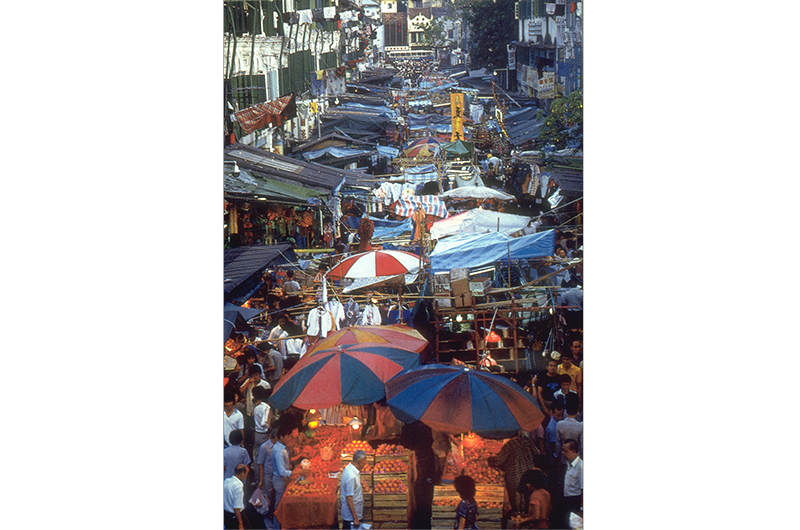

Wet markets have existed in Singapore since 1825. Zoe Yeo looks at how these markets have changed over time.

To most people in Singapore, the wet market is so much a part of the landscape that it is barely worth noticing. However, the term is not in common use around the world. It was only in early 2020, at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, that the term “wet markets” was thrust into the international limelight. The first diagnosed cases were linked to the former Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market (now closed) in Wuhan, China, in late 2019. The coronavirus was classified as a zoonotic disease,1 which raises speculation that the virus had jumped from wild animals sold at that market to humans.

To explain the concept of a wet market, the National Geographic in April 2020 described it as “large collections of open-air stalls selling fresh seafood, meat, fruits, and vegetables”. These markets “sell and slaughter live animals on site, including chickens, fish, and shellfish”. The “wet” in wet markets is attributed to “live fish splashing in tubs of water, melting ice keeping meat cold, the blood and innards of slaughtered animals”. 2 Unfortunately, “wet market” is often conflated with “wildlife market” even though most wet markets don’t sell wildlife.

Although the interest in wet markets, particularly the one in Wuhan, skyrocketed in 2020, many are unaware that the term “wet market” may have first arisen in Singapore. The term began to appear in the late 1970s. A Straits Times article published on 13 July 1978 noted that the Trade Department said that it was “reluctant to introduce the sale of frozen fish in ‘wet’ markets for fear of profiteering by hawkers” and also “fear that some hawkers may thaw the fish and sell it as fresh”.3 The use of quote marks around the word wet suggests that it was a novel term.

The term “wet market” was formally recorded in the Oxford English Dictionary in 2016 and was defined as a “market for the sale of fresh meat, fish, and produce” in Southeast Asia.4

Prior to “wet markets”, the words “market” and pasar were commonly used in local newspapers. The Malay word pasar is a loanword from “bazaar” which originated from Persia to refer to a town’s public market district.5 Pasar was so widely used locally that the transliteration of the Malay word, 巴刹 (ba sha), was coined and it became the official Chinese term used for wet markets in Singapore and in some parts of Southeast Asia.6

Singapore’s Early Wet Markets

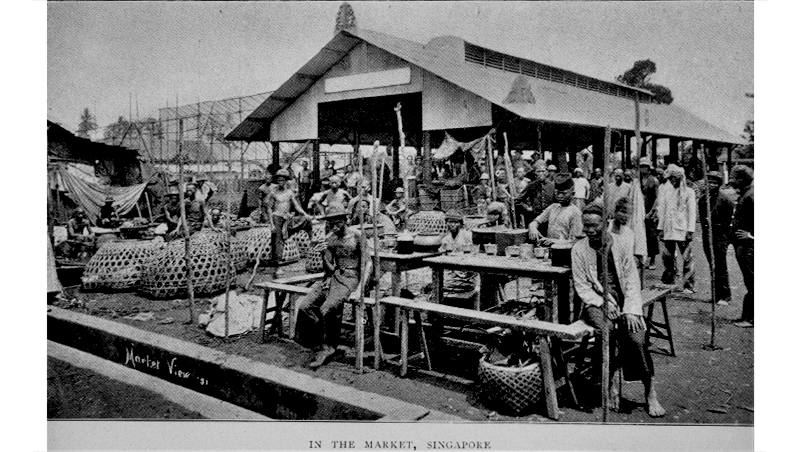

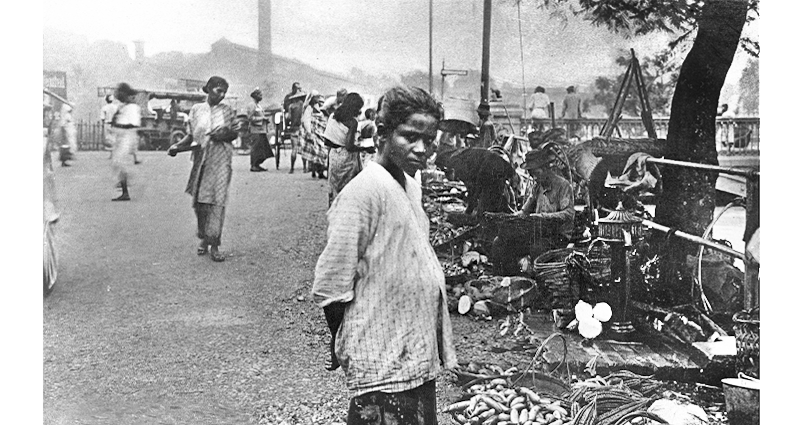

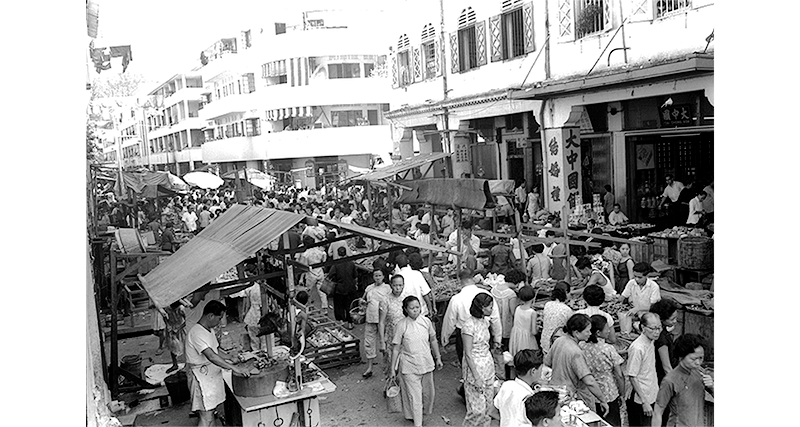

Although there is a lack of documentation on markets in the pre-colonial era, evidence shows that markets and bazaars have appeared organically where trading took place. These markets were makeshift sites scattered across the island, where vendors would lay out their produce on the ground or in baskets, in open areas or under a shed.7

The Telok Ayer Market is believed to be the first purpose-built market in Singapore. In November 1822, Stamford Raffles appointed a Town Committee to implement his vision of reorganising the town that had grown in a haphazard manner. In his directive, he wrote: “As a measure of police it is proposed to remove the fish market to Tulloh [Telok] Ayer without delay and it will be the duty of the committee to consider in how far the general concentration of the fish, pork poultry and vegetable markets, in the vicinity of each other, may not be advantageous for the general convenience and cleanliness of the place.” The fish market had originally been located near the north end of Market Street on the riverbank that had shops selling market produce.8

The market in Telok Ayer opened in 1825, a simple timber structure erected partially over the sea on timber piles so goods could be loaded and unloaded directly onto boats. The roof of the market was formed by timber trusses, covered with attap (nipah palm leaves) and supported by timber posts. However, the market was soon declared structurally unsafe as the attap roof violated fire safety regulations.9

A new building replaced the dilapidated structure at the same site in 1833. Designed by George D. Coleman, who was also the first Government Superintendent of Public Works, the new market measured 125 feet (38 m) in diameter, twice the size of the original market. It was formed by two concentric rings of brick piers arranged octagonally. There were also three arches on each side of the octagon which were “necessary for the admission of light and air”.10

English traveller Annie Brassey11 visited the market in 1877 and was impressed by what she saw. “The fish market is the cleanest, and best arranged, and sweetest smelling that I ever went through,” she wrote. “The poultry market is a curious place. On account of the intense heat everything is brought alive to the market, and the quacking, cackling, gobbling and crowing that go on are really marvelous,” said Brassey.12

Due to a land reclamation project, the market was demolished in 1879 and the market stalls relocated to newly reclaimed land at Collyer Quay. A new market – which retained the octagonal shape of the original market – was designed by Municipal Engineer James MacRitchie and completed in 1894. Operating for almost 80 years, it ceased to function as a wet market in 1972, following the area’s transformation into a commercial and financial district, and was gazetted as a national monument in 1973. Officially renamed Lau Pa Sat (Old Market) in 1989, the food centre is today a popular haunt for tourists as well as office workers in the Central Business District.13

By the end of the 19th century, the Municipal Commission had established four other markets: Ellenborough Market built in 1845, Clyde Terrace Market and Rochor Market established in the 1870s, and Orchard Road Market in 1891.14

Ellenborough Market

Ellenborough Market was located between Ellenborough Street and Fish Street (both expunged). The market was known in Malay as Pasar Bahru, which means “New Market”. It was also nicknamed “Teochew Market” as many Teochews lived in the area. The market was noted for its fresh fish and dried seafood products. However, a fire that gutted the market in January 1968, during the lunar new year, affected some 1,000 hawkers and stallholders. The remnants of the market were later demolished, and Housing and Development Board flats, a market and a hawker centre were constructed at the site in the 1970s.15 These were demolished in the 1990s to make way for Clarke Quay Central and Swissôtel Merchant Court.

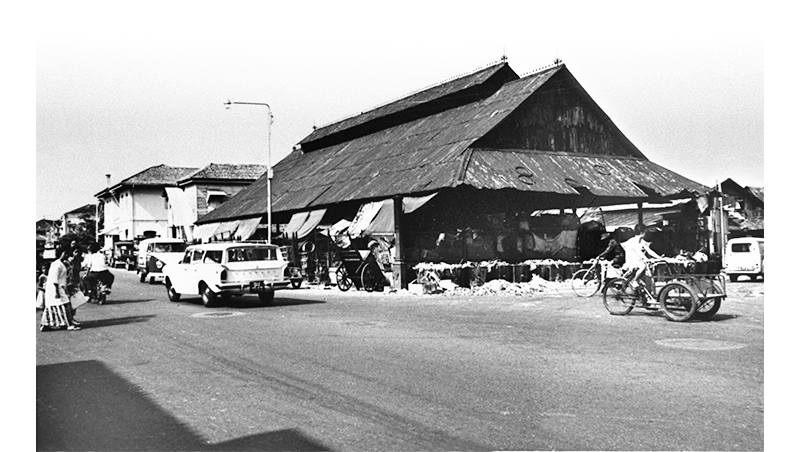

Clyde Terrace Market

Clyde Terrace Market, also known as Pasar Besi and Ti-Pa-Sat (铁巴刹), meaning “Iron Market” in Malay and Hokkien respectively, was well known for its structure that was mostly constructed of iron. The market was initially a cluster of tiled sheds at Campong (Kampong) Glam Beach. In August 1871, the sheds were described in the press as “not only disgraceful in their outward appearance, but their internal condition is anything but inviting, and it is next to impossible to keep them clean”.16

Preparations for a new market began in 1872 when iron pillars and other building materials were imported from England, with the laying of the foundation stone on 29 March 1873. Located near Clyde Terrace (present-day Beach Road) on the reclaimed stretch of land facing the sea, the market began operations around 1874. It later also functioned as a wholesale market and distribution centre where vendors purchased fresh produce and sold them in rural villages and other smaller markets.17 Clyde Terrace Market was demolished in 1983 and the Gateway office complex stands at the site today.18

Rochor Market

Rochor Market, built in 1872, was a popular landmark in the Sungei Road district. The market served the surrounding community for more than a century before it was demolished in August 1982.19 Little is known about this market and an open-air carpark occupies the site today.

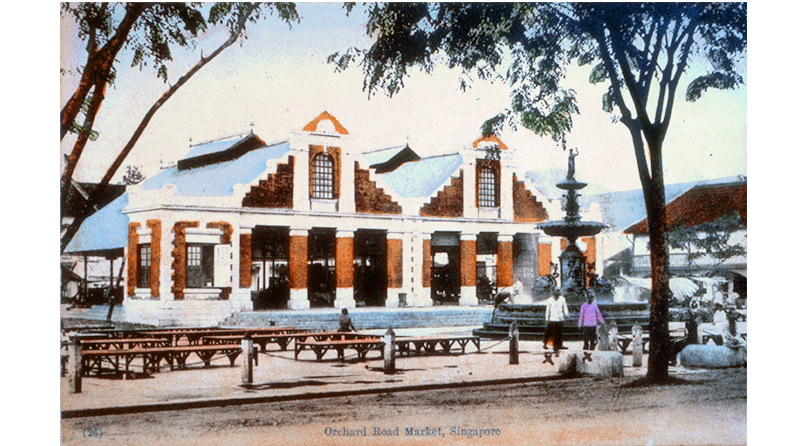

Orchard Road Market

Located at what is now Orchard Point, Orchard Road Market was known by the locals as Tang Leng Pa Sat or Tanglin Pa Sat.20 It sold fresh produce at higher prices compared to other markets in Singapore due to its wealthier European customers.21 The fountain that currently stands in the courtyard of Raffles Hotel was once located in front of Orchard Road Market.22 The market was demolished and replaced by Orchard Point in 1982.23

New-generation Wet Markets

In post-war Singapore, the government began building a new type of market that was co-located with cooked food stalls. These food stalls were manned by people who used to make a living as itinerant hawkers. A desire to remove street obstructions and to better monitor the hygiene of cooked food resulted in the setting up of hawker centres that adjoined markets.24

One of the earliest examples of this is Tiong Bahru Market, also known as Seng Poh Road Market in its early days. Opened in 1950, the market was described as a “dirty, unhygienic, crowded and messy single storey structure” by Lizzy Lee in her book, 巴刹 Pasar: The Personalities of Singapore’s Wet Markets.25

These wet markets became an integral part of new housing estates that were built. In many ways, the centre of each neighbourhood was the wet market. Over time, these wet markets underwent a series of upgrading as the authorities improved the lighting, ventilation and drainage in these structures. Today, the Tiong Bahru Market and Hawker Centre is a wheelchair-accessible two-storey building with a large central garden courtyard. The wet market is located on the first floor with the hawker centre on the second. Instead of being dark, dirty, smelly and wet, the market is airy, brightly lit, clean, mostly dry and not particularly malodorous.26

Live Slaughter of Animals

While most wet markets in Singapore were alike, there was one that was unique: Chinatown Market. This market was infamous for the sale of meat from animals such as snakes, crocodiles, monkeys, dogs, cats, rabbits and bats.27

It is believed that these animals were smuggled from outlying islands such as Pulau Ubin and neighbouring countries like Malaysia and Indonesia. The meats from these animals were sought after for their “healing properties”.28

Chinatown Market had originally consisted of stalls concentrated along Trengganu Street, Sago Street and Banda Street, with a few spilling onto Temple Street and Pagoda Street. A 1974 New Nation article noted that a stall at the junction of Smith and Trengganu streets was selling almost everything from rabbits, guinea pigs and turtles to anteaters, pythons, crocodiles and monitor lizards.29

“These are kept in makeshift cages about the stall and are only slaughtered when sold,” the newspaper added. “Pieces of various meat and entrails are also displayed for the older-generation Chinese who still believe in the curative and or strengthening powers of these exotic meats cooked with various herbs. At night, in nearby Trengganu Street, you can even buy a bowl of these brews for only $1.”30

In the early 1980s, stallholders were moved into what is now called Chinatown Complex, referred to colloquially as Chinatown Market. Some continued selling wildlife meat until the practice eventually died out, especially after Singapore became a signatory to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora in 1986.31

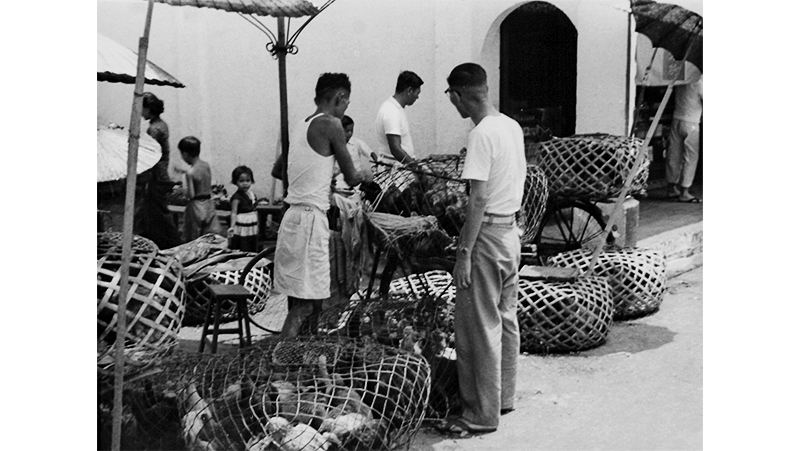

Chinatown Market was an exception though. In the other wet markets in Singapore, the only animals regularly slaughtered on the premises were chickens. Up till the 1980s, customers could select live chickens in wet markets and have them slaughtered on the spot. An estimated 69,000 birds were slaughtered daily at these markets, making up two-thirds of the total number of birds slaughtered in Singapore. As a result, “even in the cleanest markets, the poultry stalls always make their presence felt by their stench. People living near markets have also complained of the noise when live poultry is unloaded from lorries in the early morning,” said the Straits Times.32

In March 1988, Cuppage Road Market became the first wet market to sell “dressed” (pre-slaughtered and cleaned) poultry as live slaughtering was no longer carried out at the market. This was a pilot at the market to gauge public acceptance.33

There were mixed reactions from customers. “How will I know if the chicken I buy is fresh?,” asked one woman rhetorically. She noted: “[T]here’s no way you can avoid the bad smell in a wet market. Even the fish stalls have a bad smell.” However, others welcomed the change. Another woman commented that “marketing would be more pleasant and cleaner without the ‘nauseating experience’ of watching chickens being slaughtered”.34

Two years later, the Ministry of Environment announced the decision to phase out poultry slaughtering at all local markets and centralising all slaughtering at poultry service abattoirs by early 1992. According to a news report, this was to “ensure that the birds are killed in hygienic conditions and prevent pollution of drains within the wet markets”. The ministry also gave assurances that the birds would be slaughtered according to halal methods with the approval of the Islamic Religious Council of Singapore (Majlis Ugama Islam Singapura; MUIS).35

The Environment Ministry said that MUIS would issue the “halal” label to certified poultry abattoirs after the inspection of their premises. The label would be printed on a tag tied to the dressed poultry or on the wrapper of the poultry along with the date of slaughter (to indicate freshness) and the name of the abattoir.36 The slaughtering of live poultry at wet markets officially ceased from March 1993.37

While the slaughter of chickens in wet markets had stopped, the sale and slaughter of wild-caught live soft-shelled turtles continued in some wet markets. It was only in December 2020 that the sale and slaughter of live turtles and frogs at wet markets in Singapore were banned following a review conducted by the Singapore Food Agency (SFA) in consultation with the National Parks Board and the National Environment Agency (NEA).

“While the public health risks posed by such slaughtering activity are low, SFA and NEA started phasing out slaughtering and sale of live frogs and turtles at market stalls since June 2020 to further reduce the risk and improve environmental hygiene and food safety,” said the SFA.38

The Future of Wet Markets

In July 1981, the Environment Ministry convened a committee to “recommend to the Cabinet what HDB [Housing and Development Board] markets of the future should look like”. This was in response to a report on Singapore markets that had been presented to the Cabinet. The report highlighted that wet markets were not fully utilised due to their short operating hours, there were too many workers in wet markets (an estimated 10,000 to 20,000 workers) and that this labour source should be directed to trades of higher productivity, and wet markets were non-economical to operate since they consisted of mostly small-scale businesses.39

The committee, led by then Senior Parliamentary Secretary (Environment) Chor Yeok Eng, studied the matter and came to the view that wet markets should no longer be built and instead modern mini-supermarkets and air-conditioned groceries should replace these markets. The committee also recommended that starting from 1982, market stallholders be allowed to take up more than one stall in order to diversify and sell other items and that stallholders should be encouraged to extend their business hours.40

Chor noted that the lifestyle of Singaporeans had changed considerably compared to 30 years ago. One of the biggest changes was the growing number of families where both husband and wife worked. “As such, a wife has little time for marketing,” he noted. “She can afford it only on Sunday or [during her] free time.” As a result, wet markets, with the “small variety of goods and short business hours, will eventually fall short of people’s demands”.41

The last two traditional wet markets, with adjoining hawker centres, were built in Jurong East and Jurong West in 1984. Different lifestyles, changing preferences and new demands from residents were reasons cited by the HDB for phasing out wet markets. The Straits Times reported that “traditional wet markets [had] lost their popularity and the patronage of many people who prefer[red] to shop at modern supermarkets [with] more flexible marketing hours”.42

Today, there are 83 wet markets in Singapore managed by the NEA and NEA-appointed operators.43 In a survey conducted by the NEA in 2018, 39 percent of Singaporeans had not visited any wet markets in a year. This number has been steadily increasing, from 23 percent and 33 percent in 2014 and 2016 respectively.44

Apart from the waning interest in wet markets, the issue of succession is also a cause for concern. The current generation of stall owners are facing an uphill battle in convincing their children, who tend to be better educated, to take over the family business. “I think in the next 20 years or so there will be no more wet markets, there will only be supermarkets,” lamented Lim Toh Khoon, a fishmonger at Fajar Shopping Centre’s wet market.45

It remains to be seen what will happen to the wet market in the future. Will it become increasingly irrelevant as busy working people turn to the convenience of supermarkets? Or will there always be a demand for the personal touch that wet markets can offer? There is no doubt that older Singaporeans still prefer the wet market and have fond childhood memories of tagging along with their parents to the markets – experiencing the sights, smells and sounds of these local landmarks that are so uniquely Singaporean.

Zoe Yeo is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She is part of the team that oversees the statutory functions at the National Library Board. She manages the Legal Deposit function and collection, including its collection policies, workflows and enforcement as well as engagement with publishers and the public.

Zoe Yeo is a Librarian with the National Library, Singapore. She is part of the team that oversees the statutory functions at the National Library Board. She manages the Legal Deposit function and collection, including its collection policies, workflows and enforcement as well as engagement with publishers and the public.NOTES

-

Najmul Haider, et al., “Covid-19 – Zoonosis or Emerging Infectious Disease?,” Frontiers in Public Health 8, 26 November 2020, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2020.596944/full. ↩

-

Dina Fine Maron, “‘Wet Markets’ Likely Launched the Coronavirus. Here’s What You Need to Know,” National Geographic, 15 April 2020, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/coronavirus-linked-to-chinese-wet-markets. ↩

-

“Frozen Fish: Fear of Profiteering at ‘Wet’ Markets,” Straits Times, 13 July 1978, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Wet Market,” Oxford English Dictionary, accessed 3 February 2022, https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/227970#eid12103480. ↩

-

Russell Jones, ed., Loan-words in Indonesian and Malay (Leiden: KITLV Press, 2007), 235. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSEA 499.22124 LOA); Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia, “bazaar,” Encyclopedia Britannica, 31 May 2016, https://www.britannica.com/topic/bazaar. ↩

-

“巴刹: Market,” Promote Mandarin Council, last updated 11 June 2020, https://www.languagecouncils.sg/mandarin/en/learning-resources/singaporean-mandarin-database/terms/market. ↩

-

Alvin Tan, Community Heritage Series II: Wet Markets (Singapore: National Heritage Board, 2013), 5, accessed 3 February 2022, https://www.nhb.gov.sg/~/media/nhb/files/resources/publications/ebooks/nhb_ebook_wet_markets.pdf. ↩

-

Lee Kip Lin, Telok Ayer Market: A Historical Account of the Market from the Founding of the Settlement of Singapore to the Present Time (Singapore: Archives & Oral History Dept., 1983), 9–10. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RCLOS 725.21095957 LEE); Charles Burton Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times in Singapore: From the Foundation of the Settlement… on February 6th, 1819 to the Transfer to the Colonial Office … on April 1st, 1867 (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1984), 74. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 959.57 BUC) ↩

-

Lee, Telok Ayer Market, 11, 16–17. ↩

-

Tan, Wet Markets, 5; “Former Telok Ayer Market (now known as Lau Pa Sat),” National Heritage Board, last updated 2 November 2020, https://www.roots.gov.sg/places/places-landing/Places/national-monuments/former-telok-ayer-market-now-known-as-lau-pa-sat; Lee, Telok Ayer Market, 19, 21. ↩

-

In July 1876, Annie Brassey boarded the Sunbeam to travel around the world with her husband, four children and a number of pet dogs. An account of her travels was published in 1878. See Annie Brassey, A Voyage in the ‘Sunbeam’: Our Home on the Ocean for Eleven Months (London: Longmans, Green, 1878). (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RRARE 910.41 BRA; Microfilm no. NL25750); Bonny Tan, “Globetrotting Mums: Then and Now,” BiblioAsia 14, no. 2 (Jul–Sep 2018). ↩

-

John Sturgus Bastin, Travellers’ Singapore: An Anthology (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 114–17. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 959.5705 TRA-[HIS]) ↩

-

Tan, Wet Markets, 5; “Former Telok Ayer Market (now known as Lau Pa Sat)”; Lee, Telok Ayer Market, 19, 21. ↩

-

Tan, Wet Markets, 5–7; “Former Telok Ayer Market (now known as Lau Pa Sat).” ↩

-

Vernon Cornelius-Takahama, “Ellenborough Market,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published 1999; “22-storey Flats at Former Market,” Straits Times, 27 July 1971, 9; “25 Years Ago,” Straits Times, 7 February 1993, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“From the Daily Times, August 22nd. The Campong Glam Beach,” Straits Times Overland Journal, 26 August 1871, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

National Library Board Singapore, Stories from the Stacks (Singapore: National Library Board, 2020), 19. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 016.95957 SIN) ↩

-

Malay Heritage Centre, Kampong Gelam: Beyond the Port Town (Singapore: Malay Heritage Centre, 2016), 69. (From National Library, Singappore, Call no.: RSING 305.8992805957 KAM) ↩

-

Ratnala Thulaja Naidu, “Sungei Road,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published 2017. ↩

-

Stephen Sim, “Singapore Streets Have Nicknames,” Straits Times, 29 September 1949, 8; Jackie Sam, “Orchard Road in Retrospect,” Singapore Monitor, 21 October 1984, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Don’t Aid the Black Market,” Singapore Free Press, 19 May 1947, 4; “Price Chief Flays Orchard Road Market ‘Ring’”, Malaya Tribune, 5 June 1948, 1; “2 Reasons for High Food Prices,” Singapore Standard, 30 March 1951, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Gretchen Liu, Raffles Hotel (Singapore: Landmark Books, 1992), 212. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 647.94595701 LIU) ↩

-

Marsita Omar, “Orchard Road Market,” in Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Article published April 2021; Ray K. Tyers, Ray Tyers’ Singapore: Then & Now, revised and updated by Siow Jin Hua (Singapore: Landmark Books, 1993), 162, 164. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 959.57 TYE-[HIS]); “‘New Look’ Plan by URA for Orchard Rd,” Straits Times, 2 December 1978, 13. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Tan, Wet Markets, 5; “买菜光景 不同啰!” [“Grocery Shopping Scene Is Different”], 新明日报 [Xin Min Ri Bao], 8 August 1995, 16; 冯剑斌 [Feng Jianbin], “湿巴刹气数未尽” [“Not the End of Wet Markets”], 联合早报 [Lianhe Zaobao], 25 October 2009, 24. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Lizzy Lee, 巴刹 Pasar: The Personalities of Singapore’s Wet Markets (Singapore: National Library Board, 2014), 6. (From National Library, Singapore, Call no. RSING 381.1095957 LEE) ↩

-

“Tiong Bahru Wet Market,” The Best Singapore, 8 January 2021, https://www.thebestsingapore.com/best-place/tiong-bahru-wet-market/. ↩

-

Sew Teng Kwok, oral history interview by Yoo Loo Feng, 13 October 1999, MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 9 of 23. (From National Archives of Singapore, Accession no. 002209); Thian Boon Hua, oral history interview by Jesley Chua Chee Huan, 25 July 2014, MP3 audio, Reel/Disc 12 of 66. (From National Archives of Singapore, Accession no. 003888) ↩

-

Serendipity, “Inscrutably Oriental,” New Nation, 3 November 1974, 18. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Serendipity, “Inscrutably Oriental.” ↩

-

“You Could Eat Bats & Lizards Here in the Past,” New Paper, 16 October 2004, 9. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Wet Market Slaughtering To Be Phased Out by ’92,” Straits Times, 6 July 1990, 3; Tan Ban Huat, “Call for Study on Slaughter of Chickens at One Place,” Straits Times, 12 January 1982, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

L.E. Prema, “Cuppage Market to Sell Dressed Fowls Only,” Straits Times, 19 August 1987, 16. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Prema, “Cuppage Market to Sell Dressed Fowls Only.” ↩

-

“Wet Market Slaughtering To Be Phased Out by ’92”; Susan Loh and Anne Tan, “Housewives Ready to Switch to Chilled Fowl,” Straits Times, 3 August 1990, 33. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Date and ‘Halal’ Marks for Abbatoir Poultry from July 15,” Straits Times, 23 May 1992, 2; “Tags to Ensure Pre-Slaughtered Poultry is Fresh,” Straits Times, 13 March 1992, 26. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Wet Markets End Poultry Slaughtering,” Straits Times, 28 February 1993, 21. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Ang Qing, “Sale and Slaughter of Live Turtles, Frogs Banned at Wet Markets in S’pore Due to Health Concerns,” Straits Times, 14 July 2021, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/sale-and-slaughter-of-live-turtles-frogs-banned-at-wet-markets-in-spore-due-to-health. ↩

-

“Markets of the Future,” Straits Times, 20 October 1981, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Matthew Yap, “The Last Two Wet Markets,” Straits Times, 12 October 1984, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

陈映蓁 [Chen Yingzhen], “湿巴刹 人情味不打折” [”The Personal Touch of Wet Markets”], 联合早报 [Lianhe Zaobao], 14 January 2021. (From Factiva via NLB’s eResources website) ↩

-

Rebecca Metteo and Lauren Ong, “As Young Home Cooks Seek Convenience, the Fate of Singapore’s Wet Markets Hangs in the Balance,” Today, 22 June 2019, https://www.todayonline.com/singapore/young-home-cooks-seek-convenience-fate-singapores-wet-markets-hang-balance. ↩

-

Metteo and Ong, “As Young Home Cooks Seek Convenience.” ↩