How Chinese Buddhist Women Shaped the Food Landscape in Singapore

Women who practised a particular form of Buddhism set up popular vegetarian restaurants in the 1940s and 50s that met the needs of local Buddhists and also helped promote vegetarianism.

By Kelvin Tan

Impossible meatballs, oat-milk lattes and tempeh burgers. Whether it is from a desire to reduce their carbon footprint, improve their health or to avoid killing animals, more and more people around the world have started exploring a meat-free lifestyle.

Singapore is not immune to this trend either, as can be seen by the numerous plant-based restaurants that have sprung up recently. Vegetarian restaurants, however, are not a new phenomenon. One of the oldest vegetarian restaurants in Singapore is believed to be Ananda Bhavan, which serves Indian vegetarian food and opened its doors in 1924.

Chinese vegetarian restaurants, on the other hand, are of a more recent vintage. They date back to the 1940s, and a significant number were established by Chinese Buddhist women.

These women hailed from southeastern China and migrated to Singapore in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. They observed a strict vegetarian diet and spent much of their time in temples. This piece focuses on three types of Buddhist women in particular: ordained nuns, lay women (jushi; 居士), and vegetarian nuns or zhaigu (齋姑).1 Most of these women belonged to a tradition of Mahayana Buddhism, with some practicising a syncretic form that combined Daoism and Confucianism.

These women, in general, were opposed to animal slaughter and believed that a vegetarian diet would keep diseases and ailments at bay. They exercised Buddhist philanthropy alongside their faith. Through the food they produced in restaurants and temples, these women promoted their ideals to the community and contributed to Singapore’s diverse culinary landscape.

The First Female Restaurateurs

In the late 1940s and 1950s, there were at least three Chinese vegetarian restaurants in Singapore founded and managed by these Chinese Buddhist women: Loke Woh Yuen Vegetarian Restaurant (六和园素食馆), Fut Sai Kai Vegetarian Restaurant (佛世界素食社) and Bodhi Lin Vegetarian Restaurant (菩提林素食馆).

Loke Woh Yuen was established in 1946 by a close group of five women, including Jian Daxian (简达贤居士), later known as Venerable Huiping (慧平法师). (She later founded the Tse Tho Aum Temple [自度庵] in Changi, which has since moved to Sin Ming Drive.)

The women had the support of people like Venerable Cihang (慈航法师), a prominent monk from Fujian province who was also behind the first vegetarian restaurant in Penang, Phoe Thay Yuen (菩提苑素食馆), which opened in 1932.2

Located at 25 Tanjong Pagar Road, Loke Woh Yuen was well known among the Chinese Buddhist community because its food was of restaurant standard and the menu was varied. Set in a single-fronted shophouse, the restaurant was described as “bright and breezy” and was notable for its “clean yet not clinical look”.3

For people who wanted plant-based alternatives to meat dishes, the restaurant offered dishes such as vegetarian shark’s fin made from maize, and fish fillet made from sugar cane flowers.4 Vegetarian mee siam and curry were available on weekends.5

Loke Woh Yuen was entirely staffed by women, from the waiters to the cashiers and the cook. The restaurant operated for over six decades before the shutters came down for the last time in 2010.

The food served at Loke Woh Yuen was known to be tasty. Writing for the Singapore Monitor, Violet Oon wrote about her experience eating a 10-course vegetarian banquet priced at $150. For those new to Chinese vegetarian food, Oon recommended the dish of loh mei or “mixed meats”, as it “truly represents the spirit of eating vegetarian style”. She also liked the mixed cold items with its “artful simulation of mock oysters”.

She wrote: “Some people may object to this simulation of non-vegetarian food flavours but I welcome it as it takes the boredom out of eating vegetables.” Overall, she said, the “richness of flavours achieved without the aid of meats or seafoods and the visual impact that was created impressed me”.6

The restaurant was popular with many people. In addition to Chinese Buddhists, tourists would walk over from Chinatown to eat at Loke Woh Yuen. It also attracted Indian customers as well. For a long time, the restaurant was so packed that it had to set up dining tents that stretched to the main road.7

One of the earliest trustees of Loke Woh Yuen was Qiu Yulan (邱玉兰居士),8 who later became one of the founders of the Bodhi Lin Vegetarian Restaurant. Bodhi Lin was set up in January 1954 and helmed by Yang Muzhen (杨慕贞居士), who was known for her “unflagging affection” for charitable and educational causes.9

Yang was the abbess of Taoyuan Fut Tong (桃园佛堂), a temple that used to be in Tanjong Pagar but has since closed down. She was also a disciple of Venerable Cihang. With her savings, Yang bought an entire shophouse at 114 Neil Road to start Bodhi Lin restaurant.

One of her first acts was to organise a fundraiser for Nanyang University. She worked with the Singapore Buddhist Federation as well as prominent business people and religious leaders for the 10-day event in January 1954. The event welcomed diners for lunch and dinner, with each table priced at $100.10 It managed to raise $11,170, a hefty sum for a small restaurant. Yang’s act was hailed by the Chinese press as a breakthrough move for Chinese women (“此举,施为妇女界破天荒擁”).11

In March 1958, Yang organised a similar fundraiser to build wards for Kwong Wai Shiu Free Hospital (广惠肇方便留医院), where she was a trustee.12 Banquet tables were priced at $50 and $100 for dining at Bodhi Lin, and these were quickly snapped up. The three-day event ended up raising $9,880.

For the event, Taoyuan Fut Tong prepared the food, while staff from Bodhi Lin served the dishes.13 Qiu sponsored the Chinese tea, while the other vegetarian restaurant, Loke Woh Yuen, provided the dish “vegetarian pheasant” (斋雉).14

Bodhi Lin celebrated its 18th anniversary in 1972 and in a newspaper article of the period, the restaurant was described as one of the most famous vegetarian restaurants in Singapore.15 In particular, it was known for its vegetarian mooncakes, which were so famous that it even attracted customers from Malaysia.16 Bodhi Lin subsequently shuttered, but when this happened requires further research.

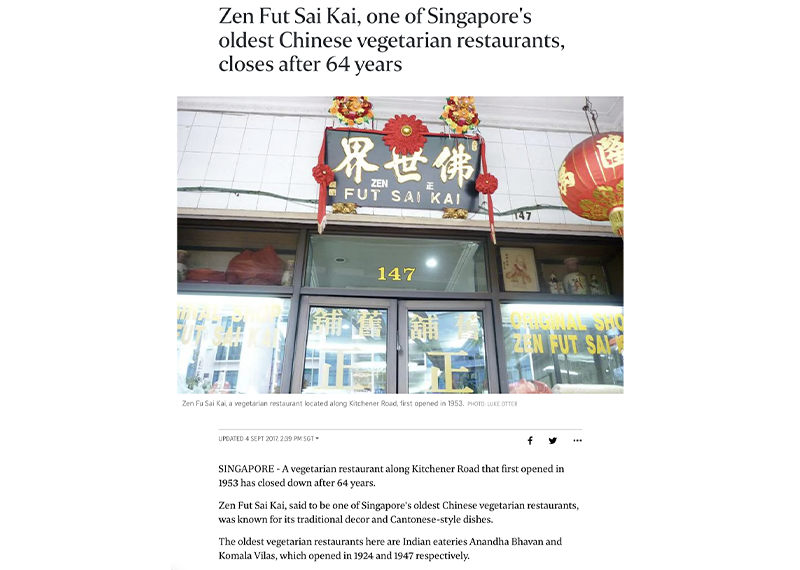

The third establishment set up by these women was Fut Sai Kai Vegetarian Restaurant. Set in an “unpretentious shophouse but with much more character than the average coffeeshop”,17 the restaurant was founded in 1953 by Ko Tian-gu (高添姑) and run by several vegetarian nuns.

Located on Kitchener Road, Fut Sai Kai was aimed at a more price conscious clientele, unlike the pricier Loke Woh Yuen. Dim sum was priced at 3 cents per plate, while noodles and dishes were between 6 cents and $1.50 respectively, similar to the prices of street food.18 Fut Sai Kai was one of the first restaurants to employ Cantonese chefs from Hong Kong. It also advertised in the Chinese press.19

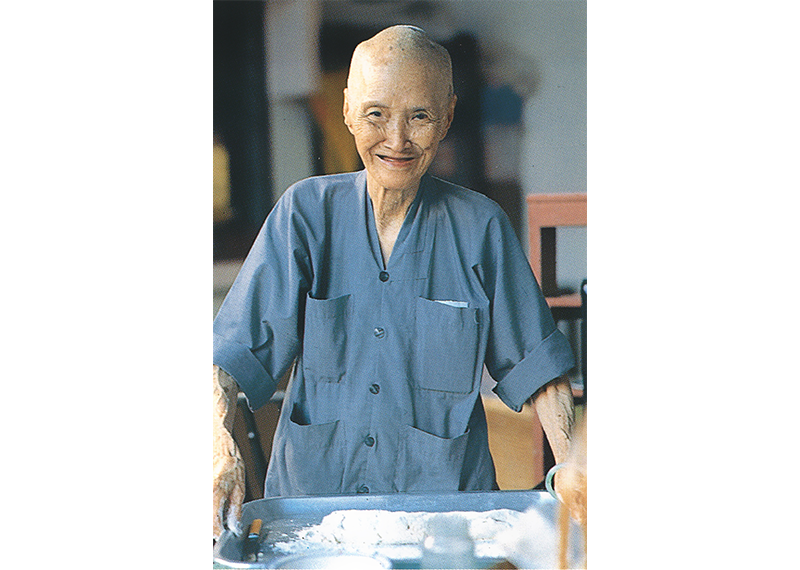

Ko was known to wake up early in the morning to buy the freshest ingredients from the market, and she also personally served customers at the restaurant. It operated from 11 am to 9 pm daily, and was packed on the 1st and 15th days of the lunar month as well as during major Chinese festivals.20

Like Loke Woh Yuen, the restaurant was also popular among non-Chinese and non-Buddhists. Tourist buses were occasionally spotted nearby as well. According to Ko, her restaurant was frequented by Christians on Fridays, and by Hindus looking for vegetarian food after temple worship.21

The food at Fut Sai Kai often received good reviews. Writing for the New Nation in 1972, Wendy Hutton was all praise for the corn soup. “I found the rather nutty, cereal flavour most enjoyable, and filled my soup bowl several times,” she said. For her, the highlight of the meal were the sugar cane flowers. “We all speculated as to whether we were eating genuine flowers, but since I’ve eaten such things as banana flower and candied violets in the past, I imagine the sugar cane flowers were authentic. A rather soft, fleshy morsel was buried inside a thick ball of butter and deep fried. Eaten with a sweet sauce, it was marvellous,” she added.22

The restaurant operated for 64 years before closing in 2017. Its closure was important enough to have warranted a news story in the Straits Times. According to the article, the owner of the restaurant had died earlier that year and the family decided to close the restaurant as there was no one to take over the cooking.23

Spreading Vegetarianism Through Temples

Restaurants were not the only way that these women promoted vegetarianism. At Choa Chu Kang’s 12-milestone (十二英里) lies the temple Hai Inn See (海印寺), which was established in 1928. Its second abbess, a vegetarian nun named Yang Qincai (杨芹菜),24 was well known for her vegetarian soon kueh. Like many temples, Hai Inn See grew vegetables and fruits on its grounds. In the 1950s, Yang Qincai discovered that bamboo plants grew well, and since the main ingredient for the kueh is bamboo shoots, she led the effort to make it regularly.25

As the fame of her soon kueh spread, the temple was invited to sell it in a nearby coffeeshop. At 5 cents a piece, it quickly became an essential breakfast item for residents. The kueh was sold from the 1960s right up till Yang’s death in 1975, and till today, customers have fond memories of her soon kueh. (The recipe of this kueh was published in the temple’s 90th anniversary commemorative book in 2018.26)

Venerable Ho Yuen Hoe (何润好), the abbess of the Lin Chee Cheng Sia (莲池精舍) temple in Kovan, was another woman who used vegetarian food for fundraising. To raise funds for Man Fut Tong (万佛堂), her temple’s new nursing home that opened in 1969, she sold vegetarian food to devotees attending dharma assemblies at the Khor Meng San Phor Kark See Monastery (光明山普觉禅寺). On average, Venerable Ho raised about $50 each day though on a good day, she could raise $80.27

When she wanted to expand the home, Venerable Ho came up with the idea of compiling her recipes into a book. Published in 1998, the book Top 100 Vegetarian Delights helped raise over $100,000 to fund the expansion. Apart from fundraising, she also wanted to use the book to promote the health benefits of vegetarianism, drawing from her belief in “renewed vitality and concentration” as means of healthy ageing.28

Venerable Ho also started giving cooking classes at Lin Chee Cheng Sia in 1987 for the growing number of devotees eager to learn vegetarian cooking from her. A long-time believer that “vegetarian food and regular exercise deliver longevity”, she hoped to share “her secrets” to “as many people as possible” while preserving her recipes.29

But Venerable Ho was not the first woman to have her vegetarian cookbook published. Jian Daxian, one of the founders of Loke Woh Yuen, and who later founded Tse Tho Aum, wrote a vegetarian cookbook in Chinese titled 素菜食谱 (Vegetarian Dishes) in 1974. The book was widely circulated in Singapore and Hong Kong, and proceeds from the sale were donated to the educational fund of the Singapore Girls’ Buddhist Institute.30

During Jian’s time at Tse Tho Aum, the temple developed a reputation for its tasty food. In February 1984, the Lianhe Wanbao (联合晚报) newspaper wrote that the dishes prepared by Jian during the Lunar New Year, including the vegetarian yu sheng, were “all but superior” to the Manchu imperial feast.31 She also taught vegetarian cooking classes.

In many ways, women like Jian Daxian, Yang Muzhen, Yang Qincai and Venerable Ho Yuen Hoe were ahead of their time. Today, the vegetarian is spoiled for choice in Singapore. Apart from the mainstay of Indian and Chinese vegetarian restaurants, there are vegetarian eateries offering Indonesian, Peranakan, Korean, Japanese and Vietnamese cuisine. Most food courts, coffeeshops and hawker centres will also have at least one vegetarian food stall. Loke Woh Yuen, Fut Sai Kai and Bodhi Lin may have faded away, but their spirit lives on.

The vegetarian soon kueh of Hai Inn See and an undated portrait of Abbess Yang Qincai. Images reproduced from 海印古寺90周年特輯 [Haiingu Temple 90th Anniversary Special] (Singapore: Hai Inn Temple, 2018), 143, 144.

The vegetarian soon kueh of Hai Inn See and an undated portrait of Abbess Yang Qincai. Images reproduced from 海印古寺90周年特輯 [Haiingu Temple 90th Anniversary Special] (Singapore: Hai Inn Temple, 2018), 143, 144.

Filling

500 g dried mushrooms, soaked

1 kg bamboo shoot

1 kg turnip

2 pieces firm beancurd

100 g sweetened beancurd sticks

2 tablespoons oil

1 tablespoon salt

1 tablespoon pepper

A dash of sesame oil

Dough skin

600 g wheat starch

300 g tapioca flour

Half tablespoon salt

Half tablespoon sugar

1200 ml boiling water

4 tablespoons oil

Method

1. Prepare the filling: Shred mushrooms, bamboo shoots, turnips, firm beancurd and sweetened beancurd sticks.

2. Heat oil in a wok and fry mushrooms till fragrant.

3. Add in bamboo shoots and turnips. Fry to mix well. Add in salt and pepper to taste.

4. Finally, mix in firm beancurd and sweetened beancurd sticks. Just before dishing the mixture out from the wok, drizzle a dash of sesame oil over the mixture. Set the mixture aside on a large plate to cool.

5. Prepare the dough skin: On a large plate, combine wheat starch, tapioca flour, salt and sugar.

6. Add in boiling water and stir the mixture constantly with a wooden ladle till well combined.

7. Mix in oil before using hands to knead the dough till smooth.

8. Divide the dough into smaller balls of equal portions. Flatten each ball of dough into a round disc to wrap a portion of the filling. Grease a steaming plate with oil before placing the soon kueh on it. Once the water starts to boil in the steamer, steam the soon kueh for about 10 minutes. After steaming, lightly brush the soon kueh with oil.

Soon kueh recipe reproduced from 海印古寺90周年特輯 [Haiingu Temple 90th Anniversary Special], Singapore: Hai Inn Temple, 2018, p. 145.

Kelvin Tan graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in history from the National University of Singapore. He was a research assistant for the project “Mapping Female Religious Heritage in Singapore: Chinese Temples as Sites of Regional Socio-cultural Linkage” funded by the National Heritage Board.

Kelvin Tan graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in history from the National University of Singapore. He was a research assistant for the project “Mapping Female Religious Heritage in Singapore: Chinese Temples as Sites of Regional Socio-cultural Linkage” funded by the National Heritage Board. NOTES

-

Show Ying Ruo, “Virtuous Women on the Move: Minnan Vegetarian Women (Caigu) and Chinese Buddhism in Twentieth-century Singapore,” 華人宗教研究 [Studies in Chinese Religions] 17 (2021): 138, 167–68, https://www.academia.edu/46956207/Virtuous_Women_on_the_Move_Minnan_Vegetarian_Women_caigu_and_Chinese_Buddhism_in_Twentieth_Century_Singapore. ↩

-

许源泰 [Xu Yuantai], 沿革与模式: 新加坡道教和佛教传播研究 [Evolution and Model: The Propagation of Taoism and Buddhism in Singapore] (Singapore: 新加坡国立大学中文系, 2013). (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 294.3095957 XYT) ↩

-

Violet Oon, “Vegetarian Food for All,” Singapore Monitor, 26 August 1984, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

洪錦棠 [Hong Jintang], 星洲唯一素食舘六和園是佛教徒開辦是婦女界所營業 [“Singapore’s Only Vegetarian Restaurant Loke Woh Yuen Was Opened by Buddhists and Managed by Women”], 南洋商报 [Nanyang Siang Pau], 23 June 1948, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Oon, “Vegetarian Food for All.” ↩

-

Oon, “Vegetarian Food for All.” ↩

-

区如柏 [Ou Rubo], 素菜馆“老大”接搬迁令 六和园临别依依 [“The ‘Master’ of Vegetarian Restaurants Receives Relocation Orders, Loke Woh Yuen Bids a Reluctant Farewell”], 联合早报 [Lianhe Zaobao], 6 October 1991, 42. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

菩提林素食館 昨日經開幕 [“Bodhi Lin Vegetarian Restaurant Opened Yesterday”], 星洲日報 [Sin Chew Jit Poh], 30 January 1954, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

菩提林素食舘 十八週年紀念 本週五設素菜 招待各界嘉賓 [“In Commemoration of Its 18th Anniversary, Bodhi Lin Vegetarian Restaurant Runs a Vegetarian Banquet This Friday to Serve Guests”], 新明日报 [Shinmin Daily News], 18 January 1972, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

菩提林素食館訂二月廿日起義賣十天全部收入捐助南大基金預料售券所得可達一萬元 [“Bodhi Lin Vegetarian Restaurant Organises a 10-day Charity Drive from the 29th, All Proceeds Go to Nanyang University and Are Expected to Reach $10,000”], 南洋商报 [Nanyang Siang Pau], 18 January 1954, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

菩提林為南大義賣 獲義款一萬餘元 黃奕歡代表南大贈旗 [“Bodhi Lin Raises Over $10,000 in a Charity Drive for Nanyang University, Huang Yihuan of Nanyang University Presents Flag”], 星洲日報 [Sin Chew Jit Poh], 3 March 1954, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

義賣齋筵爲廣惠肇醫院募籌建病樓基金 [“Vegetarian Charity Drive Raises Funds for Kwong Wai Shiu Hospital to Build Wards”], 南洋商报 [Nanyang Siang Pau], 10 April 1958, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

楊慕貞居士慷慨發起定期義賣齋筵二百席全部收入充廣惠肇醫院慈善經費桃園佛堂報効齋料菩提林負責義賣 [“Yang Muzhen Jushi Kindly Organises Periodic Vegetarian Charity Drive, All Proceeds from a 200-table Banquet Go to Kwong Wai Shiu Free Hospital, Bodhi Lin Manages Its Costs”], 南洋商报 [Nanyang Siang Pau], 3 February 1958, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

桃園佛堂楊慕貞女居士 近舉行齋券義賣 爲廣惠肇留醫院籌款 [“Taoyuan Fut Tong’s Yang Muzhen Jushi Recently Organised a Charity Drive to Raise Funds for Kwong Wai Shiu Hospital”], 星洲日報 [Shin Chew Jit Poh], 4 March 1958, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

菩提林素菜舘巧製純齋月餅 [“Vegetarian Mooncakes Made by Bodhi Lin Vegetarian Restaurant”], 南洋商报 [Nanyang Siang Pau], 30 September 1965, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

See Foon, “Vegetarian Food at Its Best,” New Nation, 7 July 1973, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

佛世界 今日開業 [“Fut Sai Kai Opens Today”], 星洲日報 [Sin Chew Jit Poh], 31 March 1953, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

第6页 广告 专栏 2 [“Page 6 Advertisements Column 2”], 南洋商报 [Nanyang Siang Pau], 31 March 1953, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

善华 [Shan Hua], 本与佛敎有深厚渊源而今随时代的进步 有益健康素食渐在我国流行 [“Singapore and Buddhism Have Strong Ties and Evolve with the Times. Healthy Vegetarian Food Is Becoming Popular in Singapore”], 新明日报 [Shinmin Daily News], 11 August 1980, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Shan, 本与佛敎有深厚渊源而今随时代的进步 有益健康素食渐在我国流行. ↩

-

Wendy Hutton, “Chicken’s Head? No, It Was Bean-Curd,” New Nation, 28 January 1972, 11. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Zen Fut Sai Kai, One of Singapore’s Oldest Chinese Vegetarian Restaurants, Closes after 64 Years,” Straits Times, 4 September 2017, https://www.straitstimes.com/lifestyle/food/zen-fut-sai-kai-one-of-singapores-oldest-chinese-vegetarian-restaurants-closes-after. ↩

-

Yang Qincai (杨芹菜, 1904–75) came to Singapore from Quemoy (Kinmen), China, in 1924 and apprenticed under Hai Inn See’s founder Yinxiu-gu. When she took over the temple’s reins in 1955, Yang grew an assortment of vegetables and fruits, including peanuts and bamboo plants, in its backyard so that the temple could be self-sufficient. ↩

-

海印古寺90周年特輯 [Haiingu Temple 90th Anniversary Special] (Singapore: Hai Inn Temple, 2018), 121. ↩

-

海印古寺90周年特輯, 145. ↩

-

陈爱玲 [Chen Ailing], 57岁出家 61岁创安老院 88老尼有个心愿 要开第二间安老院 [“Ordained at 57, Opened a Nursing Home at 61, an 88-year-old Nun Has a Wish to Open a Second Nursing Home”], 新明日报 [Shinmin Daily News], 30 September 1996, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Shi Chin Yam, Top 100 Vegetarian Delights (Singapore: Man Fut Tong Old People’s Home, 1998), preface. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 641.5636 SHI) ↩

-

Uma Rajan and G. Uma Devi, A Life for Others (Singapore: Man Fut Tong Nursing Home, 2007), 23. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 361.95957 RAJ) ↩

-

许源泰 [Hue Guan Thye], 狮城佛光: 新加坡佛教发展百年史 [The Buddha Lights of Lion City: The Hundred-year Development of Buddhism in Singapore] (Hong Kong: 香港中文大学人间佛教研究中心, 2020), 222–23. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. Chinese RSING 294.3095957 HGT) ↩

-

李若莲与蔡成才 [Li Ruolian and Cai Chengcai], 自度庵的素菜 [“Vegetarian Dishes of Tse Tho Aum”], 联合晚报 [Lianhe Wanbao], 22 February 1984, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩