Order and Cleanliness: Singapore’s Public Bathhouses of the 1880s

Three public bathhouses at Ellenborough Market, Canton Street and Clyde Terrace were built by the Municipality in the late 19th century.

By Jesse O’Neill

In late 19th-century Singapore, people had few options for getting the water they needed for washing themselves. They might have wells in their home to draw water, or they would use public ones. Those with the means could pay the tukang air (Malay for water carrier) to deliver water, while others might venture out to nearby streams. Obtaining water was difficult and required effort, and there were noted distinctions in water access between the wealthy and the poor.

As one European resident noted in the Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser in January 1866, “we have fresh water poured into the capacious vessels which serve as baths, and perhaps not one amongst us, while enjoying the pleasures thereof, considers that, there is at the moment some hundreds of fellow men, who are unable to obtain even fresh water for the purpose”.1

Because of the limited water supply system on the island at the time, it was common for many to bathe publicly in the open, making this a source of contention. Throwing ideas of race, hygiene and morality into the mix, the Municipality had to intervene, which only made accessing public washing places more difficult.

The imagined necessity of racial segregation while bathing exaggerated these problems of access. When it was suggested that merchant Cheang Hong Lim might extend his philanthropy by building a new public bathing place in Singapore in 1876, a reader wrote to the Straits Observer that this should involve separate baths, “some for Europeans, some for Eurasians and some for Natives”.2

Widespread racial distinction in water access and the resulting complaints of Europeans finally prompted the Municipality to adopt a new programme of public bathhouses for the poor and labouring classes, aided by the new infrastructure of the town’s Impounding Reservoir (now known as MacRitchie Reservoir).

This resulted in three public bathhouses being built by the Municipality in the 1880s. Located at Ellenborough Market, Canton Street and Clyde Terrace, these bathhouses relied on water piped in from the town’s reservoir. While these bathhouses were only in use for about a decade, they offer an interesting glimpse into a little-known slice of Singapore’s history.

Regulations and Restrictions

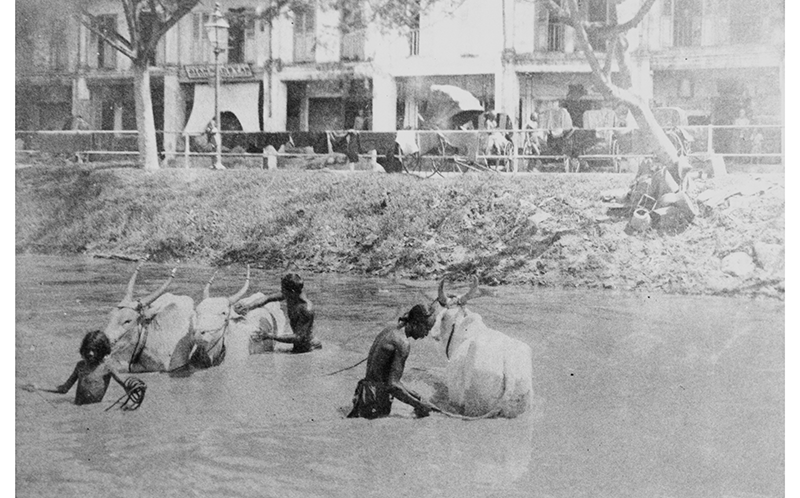

The ubiquity of public bathing produced a regular stream of reports in the local press complaining about semi-nude bodies washing in open view in places such as the Singapore River, Commercial Square and Orchard Road. “The Jury present that the public bathing in the rivulet skirting Orchard Road is a nuisance from persons being allowed to bathe in the view of the public in a state [of] nudity or nearly so, and they recommend that means should be taken to prevent this violation of public decency,” said the Straits Times in April 1849.3

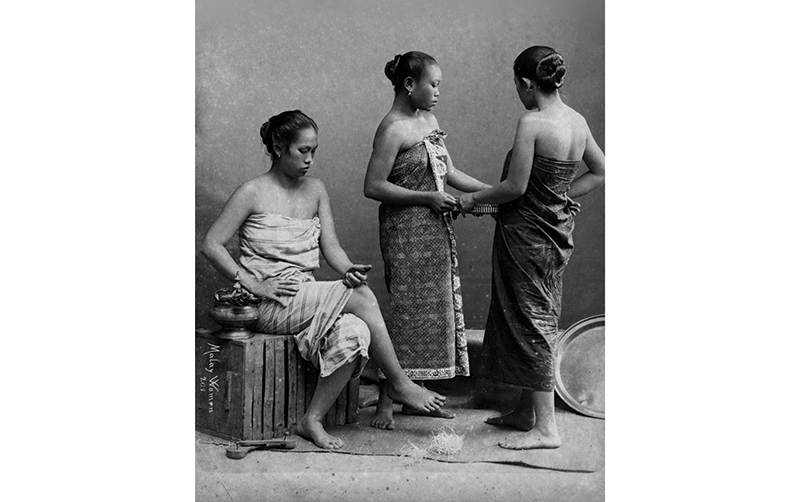

In January 1871, the Straits Times Overland Journal reported that many Indians “of both sexes not only may but must be seen here at all hours of the day, in unblushing nakedness, close beside one of our most fashionable thoroughfares, in full view from every carriage that passes”. It added that “[c]leanliness is, in itself, doubtless a very good thing, but unless it can be attained without flagrant indecorum, ceases to be wholly desirable”.4

Tensions reached an almost comedic height when the Ladies Lawn Tennis Club, a social centre for European women, was established in 1884 across from Dhoby Green, a well-known bathing place that had drawn complaints for decades.5 In June 1886, two years after the tennis club was formed, four Chinese out of a group of 15 were fined 25 cents each by A.G.L. Minjoot, Inspector of Nuisances, for indecent bathing in public in Carrington Road, opposite the Ladies Lawn Tennis Club. “We understand that Mr Minjoot, in personally arresting the 4 Chinese, met with strong resistance from the rest, who attempted to free their comrades from his grasp, but he successfully brought them to the station,” noted the Straits Times.6

There was an effort to enclose popular bathing spots with attap (nipah palm) screens or small washing rooms to obscure bathers from view. One of the earliest examples involved building brick and chunam enclosures around the wells near the Temenggong’s Istana Lama in Telok Blangah in 1849. The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser saw this as a sign of people accepting “European ideas of decency”. This, the paper noted, was an improvement over what used to happen in the past. “In former days, anyone who extended his morning’s ride to Tulloh Blangah [Telok Blangah], might see men, women, and children bathing at the numerous wells on the road side, without any screen between them and the road.”7 Over the following decades, more wells, tanks and streams were shielded from view with similar roughly built screens and structures.

In 1848, Singapore’s first Municipal Committee was established in an attempt to remove the practical administration of the town from the powers of Governor William John Butterworth, who was then proving to be a divisive figure.8 The role of the Municipality began with oversight of policing, including matters of public decency, thus leading to an involvement in questions of public bathing and water supply. From the early 1850s, Singapore’s new commissioners gained more power to regulate the town’s streets and public behaviour, and the practice of shielding bathers turned into the passing of laws to restrict and control them. The Municipality began limiting access to water for washing, designating only certain rivers and canals for bathing, and requiring every person washing there to remain decently dressed.9 Fines were imposed for bathing in the streets, or at places that had not been designated as bathing spots.

These regulations were partly driven by the European community’s ideas of morality, which saw public bathing as a nuisance, but which also responded to newer ideas about public hygiene. It was increasingly recognised that bathing bodies would contaminate drinking water and that it was similarly unhealthy to wash in polluted commercial waterways. The problem was intermingling water functions, and so the town sought to unpack and categorise Singapore’s waterbodies based on principles that merged and confused views on hygiene and morality. From this point, Singapore’s water sources were not all equal, and bathing was legally separated from other uses of water.

However, the municipal commissioners soon realised that the number of bathing places initially approved were too few, and asked the surveyor general to look into the matter in 1858. He advised establishing new bathing sites at Telok Ayer, Havelock Road, Government Hill (now Fort Canning), Orchard Road, Rochor Canal and South Bridge Road.10 This was not a provision of new water sources but rather a reclassification of water, along with the construction of some new modesty barriers.

Not all sanctioned bathing places were in the town though. There was one in Seletar, illustrated in a print by the Austrian painter Eugen von Ransonnet in 1869 when he stayed nearby, and one in Bedok that was washed away in heavy rains in December 1870.11 But bathing spots were determined by the concentration of people, so most were found in the town where they could also be most easily regulated.

Municipal Engineer W.T. Carrington’s report on the Singapore River on 4 October 1875 noted 42 public baths along the banks of this river alone, with the Rochor Canal and Kallang River also having their own official bathing places.12 And whether these were at wells, canals or in specialised tanks, the laws regulating public washing also made each of these places the responsibility of the municipal commissioners; by 1876, the town was paying $5,000 annually to maintain them.13

New Bathhouses

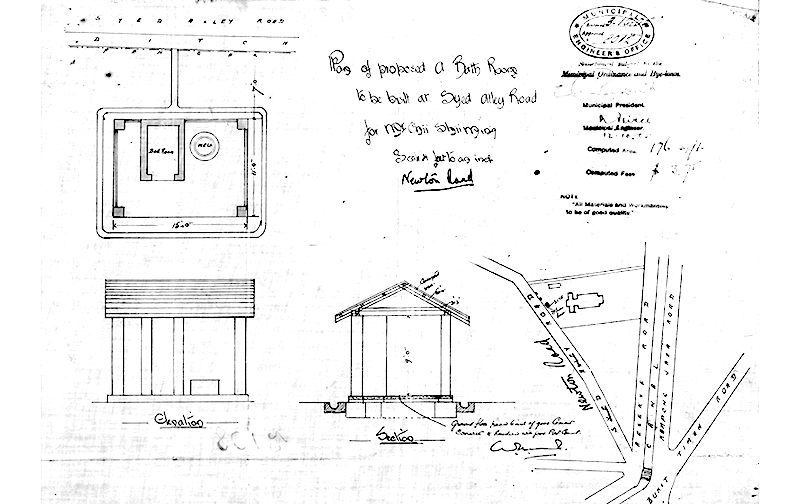

In 1878, the new municipal engineer, Thomas Cargill, was instructed to solve the perennial problem of public bathing.14 After decades of planning and construction, the Impounding Reservoir finally became operational that year. This meant that Cargill could plan a new public bathing system that used piped municipal water, rather than relying on water boats or natural sources.

It seemed that the reservoir would bypass all of the concerns about water hygiene that had plagued the municipal commissioners in recent years, which had led them to outlaw bathing in places that drinking water could be collected and consider plans for filling the polluted canals adjacent to the Singapore River.15

Cargill’s proposal for a new kind of public bathhouse was approved in December 1878. The first would be constructed at Ellenborough Market, replacing an older bath from 1874 that relied on water delivered by boats.16 The Municipality also planned a second bathhouse at Upper Cross Street, going so far as to accept construction tenders for it in 1879, before realising that the government had already reserved the land for police accommodation.17 The municipal commissioners would have to find another site for their second bathhouse, but in the meantime, the one at Ellenborough Market went ahead.

The Ellenborough Market bathhouse was opened to the public at the beginning of 1880. In February that year, its manager, Low How Chuan, asked for two gas lamps to be installed “for the convenience of persons bathing after sunset”.18

The municipal commissioners quickly took issue with the amount of water that bathers at this bathhouse were using though. There were an estimated 1,126 people using the bathhouse daily, each of whom used 17 gallons of water, or about 77 litres.19 The town water service only ran 12 hours a day to conserve water.20 Now that bathing water came from the municipality’s own underperforming reservoir, frugality needed to be enforced and a bathhouse watchman was hired to prevent wastage. This proved effective and by July 1880, water usage at the Ellenborough Market bathhouse had been reduced from 554,800 gallons in May to 414,400 gallons in June.21

Meanwhile, Cargill was planning two more bathhouses, one on Jalan Sultan and another on Canton Street over the Singapore River. The first encountered problems in acquiring land, but the second (which was the replacement site for the Upper Cross Street bathhouse) made progress.22

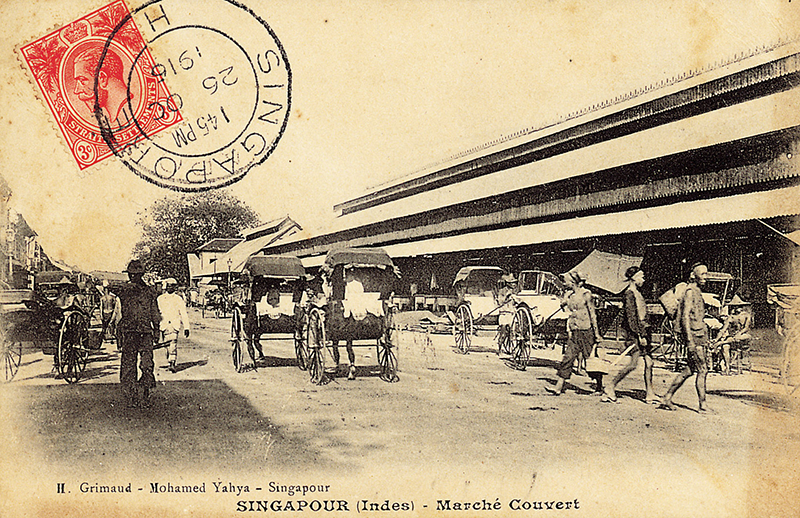

The Canton Street (Boat Quay) bathhouse was completed in early 1881 and received a glowing review in the Straits Times Overland Journal in February that year: “The substitution of tastefully designed buildings for the former rough plank partitions, and the interior arrangement of a large oblong tank, supplied with water from the waterworks, is at once such a vast improvement upon former constructions as to awaken admiration of the taste and ability of the Municipal Engineer, and the public spirit of the Commissioners, in providing such elegant public conveniences,” the paper noted. “We should be glad to see many such tasteful structures wherever convenient throughout the town.”23

The Ellenborough Market and Canton Street bathhouses were large wooden rooms with tiled roofs and painted, whitewashed walls. These were supplied by taps connected to the municipal waterworks, and each held a single iron tank for communal bathing.

There were two key distinctions between these structures and earlier municipal bathing spots. The first was that these bathhouses received clean water piped directly from the reservoir, rather than relying on water carriers collecting from sometimes questionable sources. The second was their build quality, which the Straits Times Overland Journal had described as “tasteful”. These weren’t the earlier rudimentary attap structures, but were actual examples of town architecture – no less a concealment of naked bodies, but also well built and pleasant to look at, forming part of the architectural vista of the Singapore River.

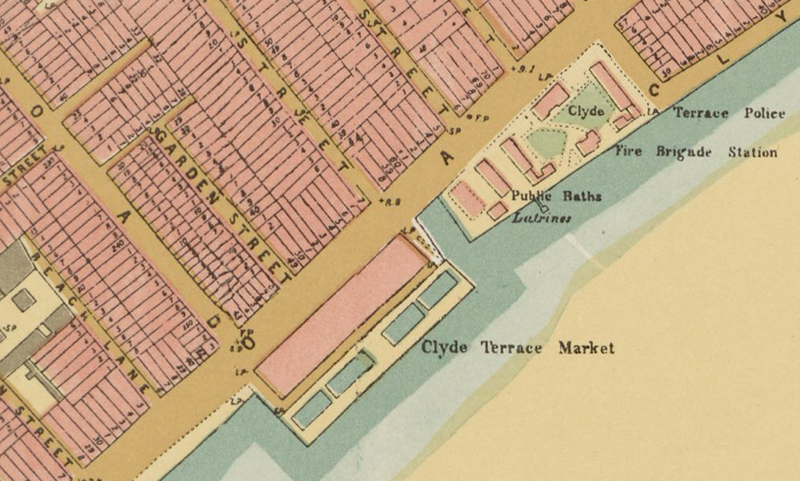

Although the proposal to build a bathhouse on Jalan Sultan was soon abandoned, plans for a third bathhouse went ahead, and in 1881, the municipal commissioners requested government land at Clyde Terrace, next to the police station and close to the market.24 The land was granted in May 1881 and construction began soon after.25

Unfortunately, an incident occurred during the building works, which damaged Cargill’s reputation. During a violent storm in August 1881, the half-finished Clyde Terrace bathhouse structure collapsed, killing two men who sheltered there from the rain. On hearing the crash, Sergeant Ramsamy ran from the neighbouring police station and saw Ngeo Tin, a revenue officer, pinned under heavy beams. He also saw an unnamed Malay fruit-seller lying nearby. Ramsamy lifted the beams from the Chinese man and discovered that he was dead. The Malay man was sent to hospital but died from head trauma 10 minutes after admission.26

At the inquest on 25 August 1881, Cargill was called to explain and defend his design and construction methods. He argued that this building used the same materials and techniques as did many other houses and municipal buildings across the town.27

The contractor for the Clyde Terrace bathhouse was Cheah Keow (also spelt as Cheah Kiow), who had also built the Ellenborough Market and Canton Street bathhouses. Cheah had installed most of the roofing tiles at the bathhouse before planning to finish the building’s side framing. This was his usual practice, he said, so that there would be shelter while the works were underway. Ultimately, this is what made the building unable to withstand the storm.28

Superintendent of Works J.H. Callcott also suspected that the supporting struts were removed early so that they could be used for another job, further weakening the structure. While the coroner reprimanded Cheah for this, he eventually ruled the deaths an accident.29

There was much unhappiness over the verdict. Discussions surrounding the evidence and the potentially conflicting roles of people involved continued in the press and in municipal meetings.30 One letter to the newspaper thought that the accounts given by Cargill and his deputy were incongruous, suggesting they had neglected their public duty to safety.31

While the Clyde Terrace bathhouse was eventually finished in December 1881 and Cheah bore the additional costs for completing it, some members of the public were increasingly questioning if Cargill and his assistant were really to blame for the tragedy.32 Cargill eventually sued two writers of the Straits Intelligence for libel in February 1883, shortly before leaving his position in August that year.33 He did, however, remain in Singapore, establishing a civil engineering office and going on to contribute to the design and construction of the third Coleman Bridge in 1886.34

A Decade of Decline

The three bathhouses designed by Cargill were in use for another decade, but newspapers made no announcements of new bathhouses after the Clyde Terrace inquest.

Throughout the 1880s, these bathhouses drew attention because of the amount of water they used, or because of the occasional tensions between the municipality and the bathhouse operators. When completed, the right to manage these places was contracted out. The bathhouse operator then had rights to charge a fixed entry fee and run the place as a business, but he also had to pay agreed rates for town water. The role was re-tendered each year.35

In April 1881, Seng Yong Cheng, who managed the bathhouses at Ellenborough Market and Canton Street, asked to have his water rates reduced but was rejected.36 Although he claimed a loss on the business, the Municipality argued that there was disparity in the water used between the two bathhouses. In the previous month, Ellenborough Market attracted 15,339 bathers, who each used 16 gallons, while Canton Street drew only 3,687 people, each using 24 gallons.37 The municipal commissioners argued that if bathers at Canton Street could be encouraged to only use as much water as those at Ellenborough Market, then the business would begin to turn a profit. The town was keen not to lose any revenue on their very expensive water system.

Every bather who visited these places was charged an entry fee of one cent, in comparison to the five- or 10-cent bath options at private bathhouses like the Waterfall Club at the foot of Pearl’s Hill.38 (The Waterfall Club, also known as the “Singapore Waterfall” was described in the press as being largely unknown to Europeans, but popular with Chinese, Malay and Indian residents. In addition to being a place for washing, it also boasted a billiard table and a bar, providing a social function that was very different from the municipal bathhouses.39 The Waterfall Club opened in 1878 but it is not known how long it lasted.)

The fixed pricing of municipal bathhouses limited the operators’s ability to build revenue, but also shows that these places were imagined as a public service to provide clean and affordable bathing for the large local working population. When the Tanjong Pagar Dock Company requested town water for a bathhouse on their land, the Municipality placed the same one-cent fee as a condition.40

The Municipality also appeared to use its power to prevent direct competition affecting their bathhouses. Low How Chuan, the first operator of the Ellenborough Market bathhouse, complained of water boat operators taking his business. An older bathing stage on the river nearby had been removed, but the boatmen installed planks for people to bathe on their boats. There was no use of town water supply here, so the municipal commissioners pushed the complaint onto the master attendant.41

The municipal commissioners did, however, reject a request from a Peter Ryapen asking for municipal water for his private bathhouse on Victoria Street, and took issue with a man in Tanjong Pagar who built his own bathing box and charged one cent for washing.42 It was deemed that municipal bathhouses had the right to regulate washing places that distributed reservoir water, and the municipal commissioners clamped down on anyone else who tried to profit from the town’s water supply.

By the end of the 1880s, the profits of municipal bathhouses were diminishing; people became less likely to visit bathhouses as the domestic service of piped water improved. On 8 May 1889, the municipal commissioners reported that the municipal revenue from these bathhouses was only $600, which was outstripped by the $800 running costs, resulting in a loss of $200.43

In 1890, bathhouse operator Tan Beng Wan asked the commissioners why he was facing decreased revenue. The response was that more members of the “coolie class” now had piped water for washing at home.44 That he even asked this question suggests that Tan was not pleased about having bought into a failing endeavor, but both he and the Municipality were then facing a change in public attitude that was finally starting to accept reservoir supply and the payment of water bills.

The Clyde Terrace bathhouse was better utilised by the public, so Municipal Engineer James MacRitchie suggested closing the two at Ellenborough Market and Canton Street. However, the municipal commissioners preferred keeping them a while longer. The bathhouse on Canton Street would be repaired while the one at Ellenborough Market would be maintained for at least another year; it was going to be demolished when the market was rebuilt anyway.45 The municipal commissioners were gradually accepting that, as the Straits Times reported, “in the heart of the town it was now impossible to make bathing-houses pay”.46

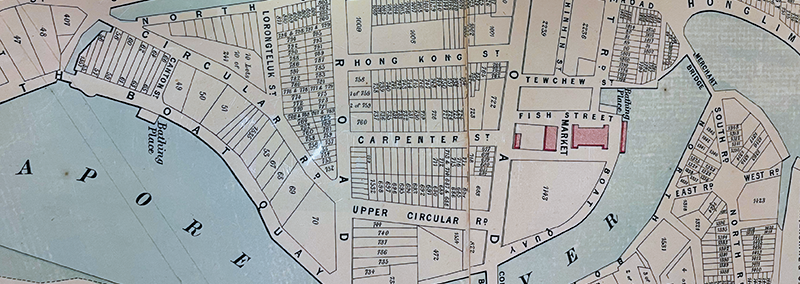

There were no further press references to the bathhouses after this. An 1893 map of Singapore town shows the bathhouses at Canton Street and Clyde Terrace Market, but not the one at Ellenborough Market.47 Unfortunately, there were no further town surveys of Singapore in the 19th century, so it is unknown when precisely the remaining bathhouses were removed. It is clear that both were being left to deteriorate before their removal; most likely, both were gone by 1895 at the latest.

From 1892, as municipal bathhouses were in their final decline, the press began once more paying increased attention to illegal public bathing, with cases being reported on Hill Street, Selegie Road, Anson Road and elsewhere on the island.48 In March 1896, the Mid-day Herald reported that there was a need for a bathhouse near Telok Ayer Market to prevent the common practices of informal public bathing.49 This harks back to the kind of language used in the press before the introduction of municipal bathhouses, and suggests that by this time, bathing options had been significantly reduced.

By the mid-1890s, the Municipality also uncovered more places using public water to operate illegal bathhouses. Tap water was charged on fixed rates then, so there were no additional costs for keeping it running. Most of these were coolie lodging houses or rickshaw depots, where large groups of men lived or congregated.50

Illegal bathhouses were found on Cross Street, Tanjong Pagar Road and Craig Road. The expansion of domestic piped water connections had prompted the closure of public bathhouses, but this in turn encouraged illegal operations to fill the continuing need for bathing, especially after the Municipality also began investigating and closing contaminated wells.51

By the end of the 19th century, Singapore’s water sources were changing, but there was still conflict between those who supplied the new infrastructure and those who had their old access to water cut off.

Cargill’s public bathhouses are only part of a wider story about how people in Singapore accessed water in the 19th century.52 Even as these public bathhouses operated, older-style bathing places with simple screens and non-piped water continued in places such as Short Street, along the Singapore River, in Bukit Timah and at water pipes in Serangoon.53 And as long as these bathing spots remained, so did the complaints in the press about public indecency.54

The municipal bathhouse programme produced only three defined structures, and the fact that they lasted little more than a decade shows them as a transitional feature in Singapore’s history of water access. These bathhouses came from a time when public and open bathing was common, where racial and colonial discourse maligned the sight of the naked poor who tried to clean themselves. The bathhouses were part of a longer policy that tried to obscure public washing, and which fused morality with ideas of hygiene to try to permanently separate and classify the functions of different bodies of water.

Municipal bathhouses also brought early access to the town’s reservoir, which aimed to provide centralised water distribution. But as the reservoir scheme gradually succeeded and more homes were connected to the town supply, these municipal bathhouses became less important. By the mid-1890s, Singapore’s public bathhouses had faded into oblivion.

Dr Jesse O’Neill is a design historian and senior lecturer at the Chelsea College of Arts, University of the Arts London. His research focuses on the materiality of modernising lifestyles in the former British colonies of Southeast Asia. He has previously written on Singapore’s postwar swimming pools, garden city planning, design promotions and colonial pavilions at the British Empire Exhibition.

Dr Jesse O’Neill is a design historian and senior lecturer at the Chelsea College of Arts, University of the Arts London. His research focuses on the materiality of modernising lifestyles in the former British colonies of Southeast Asia. He has previously written on Singapore’s postwar swimming pools, garden city planning, design promotions and colonial pavilions at the British Empire Exhibition.NOTES

-

“The Singapore Free Press,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 11 January 1866, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Nemo, “A Growler,” Straits Observer, 11 July 1876, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“To Correspondents,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 19 October 1843, 2; “The Free Press,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 19 April 1849, 2; “The Grand Jury’s Presentment,” Straits Times, 25 April 1849, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Tuesday 10th January,” Straits Times Overland Journal, 18 January 1871, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Singapore Free Press,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 11 January 1866, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Local and General,” Straits Times Weekly Issue, 17 June 1886, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Free Press,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 1 February 1849, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

C.M. Turnbull, A History of Modern Singapore 1819–2005 (Singapore: NUS Press, 2009), 83. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 959.57 TUR-[HIS]) ↩

-

“Municipal Commissioners,” Straits Times, 16 December 1856, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Municipal Commissioners,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 1 April 1858, 3; “Municipal Commissioners,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 20 May 1858, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Untitled,” Straits Times, 31 December 1870, 2. (From NewspaperSG); Eugen von Ransonnet, “Bathing Place Near Selita,” chromolithograph, 45.4 × 49 cm, 1869, National Museum of Singapore, last updated 2 April 2021, https://www.roots.gov.sg/Collection-Landing/listing/1149079. ↩

-

“Municipal Engineer’s Office,” Straits Observer, 8 October 1875, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Municipal Commissioners,” Straits Times, 29 July 1876, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Municipality,” Straits Times, 26 October 1878, 1. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Legislative Council,” Straits Times Overland Journal, 29 June1872, 6; “Municipal Commissioners’ Office,” Straits Times Overland Journal, 2 June 1878, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Untitled,” Straits Times, 21 December 1878, 5; “Municipal Commissioners,” Straits Times, 21 February 1874, 2; “Municipal Commissioners,” Straits Times, 21 March 1874, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Municipality,” Singapore Daily Times, 26 May 1879, 3; “The Municipality,” Singapore Daily Times, 22 July 1879, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Municipality,” Singapore Daily Times, 19 February 1880, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Municipality,” Singapore Daily Times, 18 March 1880, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Brenda S.A. Yeoh, Contesting Space in Colonial Singapore: Power Relations and the Built Environment (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 2003), 178. (From National Library, Singapore, call no. RSING 307.76095957 YEO) ↩

-

“Municipal Engineers Office,” Singapore Daily Times, 19 February 1880, 3; “The Municipality,” Singapore Daily Times, 3 August 1880, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Municipality,” Singapore Daily Times, 4 August 1880, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Wednesday 2nd February,” Straits Times Overland Journal, 9 February 1881, 7. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Municipality,” Singapore Daily Times, 15 December 1880, 2; “The Municipality,” Singapore Daily Times, 14 March 1881, 3; “The Municipality,” Singapore Daily Times, 14 May 1881, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Municipality,” Singapore Daily Times, 10 June 1881, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Untitled,” Straits Times Overland Journal, 25 August 1881, 6; “The Fallen Bathing House: The Inquest,” Singapore Daily Times, 26 August 1881, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Friday 26th August,” Straits Times Overland Journal, 1 September 1881, 7; “From the Daily Times, 4th October,” Straits Times Overland Journal, 8 October 1881, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Fallen Bathing House,” Straits Times Overland Journal, 9 September 1881, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“From the Daily Times, 28th December,” Straits Times Overland Journal, 31 December 1881, 3; “The Fallen Bathing House,” Straits Times Overland Journal, 8 October 1881, 10. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Supreme Court,” Straits Times Weekly Issue, 26 February 1883, 6; “Testimonial to the Municipal Engineer,” Straits Times, 27 August 1883, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Municipality,” Straits Times, 5 November 1886, 3; “The Municipality,” Straits Times Weekly Issue, 15 November 1886, 8. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Municipality,” Singapore Daily Times, 16 December 1879, 3; “The Municipality,” Singapore Daily Times, 19 February 1880, 2; “The Municipality,” Straits Times, 17 January 1884, 3; “Municipal Notice,” Straits Times, 22 November 1884, 122. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Municipality,” Singapore Daily Times, 5 April 1881, 3; “The Municipality,” Singapore Daily Times, 14 April 1881, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Municipal Engineer’s Office,” Singapore Daily Times, 14 April 1881, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Page 2 Advertisements Column 4,” Singapore Daily Times, 4 June 1878, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“An Unknown Club,” Singapore Daily Times, 17 May 1878, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Municipality,” Singapore Daily Times, 19 February 1880, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“The Municipality,” Singapore Daily Times, 26 May 1879, 3; “The Municipality,” Singapore Daily Times, 14 September 1880, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Municipal Commissioners,” Straits Times, 9 May 1889, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Municipal Commission,” Straits Times Weekly Issue, 18 February 1890, 4. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Municipal Commissioners”; “The Municipal President’s Progress Report for May 1889,” Straits Times Weekly Issue, 20 June 1889, 5. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Survey Department, Singapore, Plan of Singapore Town Showing Topographical Detail and Municipal Numbers, map, 1893. (From National Archives of Singapore, accession no. SP002988) ↩

-

“Correspondence,” Daily Advertiser, 10 August 1892, 3; “Local and General,” Mid-day Herald, 11 May 1895, 3; “Long Shore and Nautical Chat,” Straits Times, 25 September 1895, 3; “The Daily Advertiser Monday Aug. 1, 1892,” Daily Advertiser, 1 August 1892, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“A Standing Nuisance,” Mid-day Herald, 31 March 1896, 2. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

“Municipal Commission,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 7 May 1896, 3. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

Yeoh, Contesting Space in Colonial Singapore, 183. ↩

-

See Lim Tin Seng, “Four Taps: The Story of Singapore Water,” BiblioAsia 14, no. 1 (April–June 2018), 50–57. ↩

-

“The Municipality,” Singapore Daily Times, 17 November 1880, 3; “The Singapore Canal,” Singapore Daily Times, 18 March 1881, 2; “Municipal Engineer’s Office,” Straits Times Weekly Issue, 28 June 1883, 12; “Notes from the Kampong,” Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 26 June 1886, 380. (From NewspaperSG) ↩

-

For examples, see “Correspondence,” Singapore Daily Times, 11 May 1881, 3; “Before N.B. Dennys, Esq. Second Magistrate,” Straits Times Weekly Issue, 16 April 1883, 1; “Municipal Engineer’s Office”; “Local and General,” Straits Times Weekly Issue, 17 June 1886, 2; “Local and General,” Straits Eurasian Advocate, 28 April 1888, 6. (From NewspaperSG) ↩